1 Kings 22 is the 22nd (and the last) chapter of the First Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible or the first part of Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter belongs to the section comprising 1 Kings 16:15 to 2 Kings 8:29 which documents the period of the Omrides.[4] The focus of this chapter is the reign of king Ahab and Ahaziah in the northern kingdom, as well as of king Jehoshaphat in the southern kingdom.[5]

| 1 Kings 22 | |

|---|---|

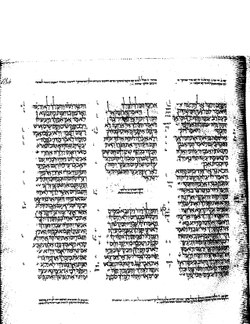

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | First book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 11 |

Text

editThis chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language and since the 16th century is divided into 53 verses in Christian Bibles, but into 54 verses in the Hebrew Bible as in the verse numbering comparison table below.[6]

Verse numbering

edit| English | Hebrew |

|---|---|

| 22:1-43a | 22:1-44 |

| 22:43b | 22:44 |

| 22:44-53 | 22:45-54 |

This article generally follows the common numbering in Christian English Bible versions, with notes to the numbering in Hebrew Bible versions.

Textual witnesses

editSome early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[7] Fragments containing parts of this chapter in Hebrew were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, that is, 6Q4 (6QpapKgs; 150–75 BCE) with extant verses 28–31.[8][9][10][11]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[12][a]

Old Testament references

editDeath of Ahab (22:1–40)

editDespite the announcement that his punishment for his crime against Naboth only befell his sons and he seemed to die of natural causes (1 Kings 22:40), Ahab was not left unreprimanded.[15] The narrative of his death displays much life of Ahab into a single climactic story:[16]

- Ahab was confronted by a prophet (this time Micaiah ben Imlah), as he was warned throughout his reign by other prophets, such as Elijah (1 Kings 17:1 for worshipping Baal and 1 Kings 21 for murdering and taking vineyard from Naboth) and an unnamed prophet for sparing Ben-hadad, the king of Aram (1 Kings 20). Despite his efforts to elude his fate, Ahab was dead according to the words of YHWH through Micaiah.

- he fought Arameans, as he had before (1 Kings 20);

- his building projects are mentioned again (as mentioned in 1 Kings 16:32–34)[16]

Three prophets, three warnings, three witnesses; these are the sign of Yahweh's continuing mercy to Ahab and Ahab cannot plead ignorance nor innocence: first warning, Ahab became sullen and angry; second warning, Ahab showed repentance; third warning: Ahab defiantly went to battle in disguise, but he got three chances, so it was strike three, in the third year (1 Kings 22:1), and he was removed.[16]

The peace between Aram and Israel following the Battle of Aphek (1 Kings 20) lasted three years, Ahab decided to capture the strategic Transjordan trading hub, Ramoth Gilead, while he made use of the close ties between the kingdoms of Judah and Israel (remained until the rise of Jehu and Joash (2 Kings 9–11)).[17] Ahab did not hesitate to sacrifice Jehoshaphat (Ahab advised Jehoshaphat not to disguise) to the enemy in order to save himself who went in disguise (verses 29–30). However, the results were different (verses 31–36), as Jehoshaphat remained unhurt whereas a stray arrow hit Ahab and he could not leave the battlefield until evening (verse 38; related to Elijah's prophecy in 1 Kings 21:19).[5]

The narrative also has an underlying theme of the battle between true and false prophecy (first initiated in 1 Kings 13).[16] A fundamental problem regarding the prophets is the unaccountability of their own attitude towards God's messages (as in Jeremiah 28 and Micah 3:5–8). Micaiah ben Imlah states that the 'prophets' with opposing messages were possessed by an evil spirit who helped to drive Ahab to death, because he witnessed the discussions at a heavenly council (in a vision, cf. Isaiah 6). Just as Isaiah's warning to the people was ignored (Isaiah 6:9–10), Micaiah's message for Ahab to change course was not heard, so Ahab would meet his doom according to the true prophecy from YHWH.[5]

Verse 1

edit- And they continued three years without war between Syria and Israel.[18]

- "Three years without war": These three years were not full years (based on verse 2), but were to be counted from the second defeat of Ben-hadad (1 Kings 20:34–43).[19] George Rawlinson conjectures that during this period the Assyrian invasion under Shalmaneser III took place and as stated in the Black Obelisk 'Ahab of Jezreel' joined an alliance of kings (including Ben-hadad of Syria) against the Assyrians, furnishing a force of 10,000 footmen and 2000 chariots.[20]

Verse 2

edit- And it came to pass in the third year, that Jehoshaphat the king of Judah came down to the king of Israel.[21]

- "The third year": during the peace between Syria and Israel, not after the event involving Naboth.[19] The marriage of Jehoram, son of Jehoshaphat, with Athaliah, the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel, would have taken place some years before this date (2 Chronicles 18:1, 2).[19]

- "Came down": The journey from Jerusalem to the provinces was termed as "going down", whereas the trip to Jerusalem as "going up".[19]

Jehoshaphat, the king of Judah (22:41–50)

editJehoshaphat was officially introduced, after the report that he was closely linked to Ahab, supporting the statement in the Annals that there was no war with Israel during his reign.[5] The kingdom of Judah at this time controlled Edom and therefore had access to the Red Sea at the seaport of Ezion-geber, but they lacked the nautical skill to undertake trade projects and the big ships (the type which can sail to Tarshish) were wrecked at the harbor [5][17]

Verses 41–42

edit- 41 And Jehoshaphat the son of Asa began to reign over Judah in the fourth year of Ahab king of Israel.

- 42 Jehoshaphat was thirty and five years old when he began to reign; and he reigned twenty and five years in Jerusalem. And his mother's name was Azubah the daughter of Shilhi.[22]

- Cross reference: 2 Chronicles 20:31

- "In the fourth year of Ahab": in Thiele's chronology (improved by McFall), Jehoshaphat became coregent in Tishrei (September) 873 BCE (Thiele has 872 BCE, on the 39th year of Asa, his father), and starting to rule as a sole king on the 4th year of Ahab between September 870 and April 869 BCE (when Asa died) until his death between April and September 848 BCE.[23] It is not clear whether Jehoshaphat was 35 years of age when he became coregent or when he became king; his age of death would be at 59 if the former, or at 56 if the latter.[23]

Verse 43

edit- a And he walked in all the ways of Asa his father; he turned not aside from it, doing that which was right in the eyes of the Lord

- b nevertheless the high places were not taken away; for the people offered and burnt incense yet in the high places.[24]

Verse 22:43b in the English Bible is numbered as 22:44 in the Hebrew text (BHS).[6]

Ahaziah, the king of Israel (22:51–53)

editAhaziah, Ahab's son and successor, followed the footsteps of his father and his mother in his short reign, so did not change the punishment of Omri's dynasty which was only postponed.[5]

Verse 51

edit- Ahaziah the son of Ahab began to reign over Israel in Samaria the seventeenth year of Jehoshaphat king of Judah, and he reigned two years over Israel.[25]

- "In the 17th year of Jehoshaphat": in Thiele's chronology (improved by McFall), Ahaziah became king between April and September 853 BCE, and he died between April and September 852 BCE.[26]

Verse 52

edit- He did what the Lord considered evil. He followed the example of his father and mother and of Jeroboam (Nebat’s son) who led Israel to sin. [27]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The whole book of 1 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[13]

References

edit- ^ Halley 1965, p. 198.

- ^ Collins 2014, p. 288.

- ^ McKane 1993, p. 324.

- ^ Dietrich 2007, p. 244.

- ^ a b c d e f Dietrich 2007, p. 248.

- ^ a b Note [b] on 1 Kings 22:43 in NET Bible

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Ulrich 2010, p. 328.

- ^ Dead sea scrolls - 1 Kings

- ^ Fitzmyer 2008, pp. 104, 106.

- ^ 6Q4 at the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b c d e 1 Kings 22, Berean Study Bible

- ^ Dietrich 2007, p. 247.

- ^ a b c d Leithart 2006, p. 158.

- ^ a b Coogan 2007, p. 530 Hebrew Bible.

- ^ 1 Kings 22:1 KJV

- ^ a b c d Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (Editors). On "1 Kings 22". In: The Pulpit Commentary. 23 volumes. First publication: 1890. Accessed 24 April 2019.

- ^ Rawlinson, George (1871). Historical Illustrations of the Old Testament. Christian Knowledge Society. pp. 113, 114.

- ^ 1 Kings 22:2 KJV

- ^ 1 Kings 22:41–42 KJV

- ^ a b McFall 1991, no. 19.

- ^ 1 Kings 22:43 KJV or 1 Kings 22:43–44 in Hebrew Bible

- ^ 1 Kings 22:51 MEV

- ^ McFall 1991, no. 21.

- ^ 1 Kings 22:52 GW

Sources

edit- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 978-1451469233.

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195288810.

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–266. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2008). A Guide to the Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Literature. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802862419.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300188271.

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.

- McFall, Leslie (1991), "Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles" (PDF), Bibliotheca Sacra, 148: 3–45, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-27

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D, eds. (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Thiele, Edwin R., The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, (1st ed.; New York: Macmillan, 1951; 2d ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965; 3rd ed.; Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983). ISBN 9780825438257

- Ulrich, Eugene, ed. (2010). The Biblical Qumran Scrolls: Transcriptions and Textual Variants. Brill.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

edit- Jewish translations:

- Melachim I - I Kings - Chapter 22 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 1 Kings chapter 22. Bible Gateway