The 1970 Idaho gubernatorial election took place on November 3 to elect the governor of Idaho, concurrently with other scheduled governor races, as well as Idaho's two congress members in the House of Representatives and a number of statewide offices. Incumbent Republican governor Don Samuelson sought re-election to a second consecutive term as governor. Although he faced a primary challenger, former state senator Dick Smith, he received more than 58 percent of the primary vote, and thus secured the party's re-nomination.[1]

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

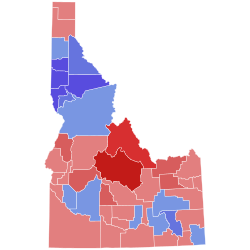

County results Andrus: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% Samuelson: 50-60% 60-70% 70-80% 80–90% | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Democratic nominee, Cecil Andrus, had previously run for governor in 1966, after Democratic nominee Charles Herndon was killed in a plane crash in the central Idaho mountains in mid-September.[2][3]

Andrus faced two competitors in the primary: state representative Vernon Ravenscroft and attorney Lloyd Walker. In the party primary, Andrus won a plurality of 29,000 votes (46 percent), and earned the Democratic nomination.[4] During the general election campaign, issues of contention included environmental conservation, taxes, and education funding.[5]

In the rematch of 1966, Andrus won the general election of 1970 with 128,004 votes, or 52.22 percent of the ballots cast.[6] He carried all regions of the state except for the south-central region; however, he significantly under-performed in rural areas, where Democrats usually achieved their highest margins, while exceeding expectations in the state's affluent urban areas.[5]

The general election campaign was then one of the most costly in Idaho's history; however, voter turnout was unusually low, at 67 percent of the voting-age population. Despite the Democrats' victory in the gubernatorial election, their success failed to trickle down the ballot: Andrus was one of only two Democrats to win a statewide office in the election, and both of Idaho's seats in the U.S. House of Representatives remained in the hands of Republicans.[7]

This was the first of six consecutive Democratic gubernatorial victories, unbroken until 1994, with Andrus winning four. This is the last time that an incumbent governor of Idaho lost re-election.

Background

editFour years earlier, Samuelson (then a state senator) soundly defeated three-term incumbent Republican governor Robert Smylie in the GOP primary. Samuelson's decision to challenge Smylie was driven largely by his opposition to the governor's proposal and signing of the first sales tax in Idaho history. Samuelson had opposed the proposed sales tax while a state senator, and received 61 percent in the primary.[8] In the general election, Samuelson had initially expected to face Democratic nominee Charles Herndon, the favorite nominee of Idaho political boss Tom Boise. However, Herndon died in a plane crash weeks before election day, and the Democrats chose state senator Cecil Andrus (who had placed second to Herndon in the primary earlier that year) as a replacement candidate. Samuelson won election by 10,800 votes, or 4.3 percentage points; more than 54,000 votes went to third-party candidates.[9]

As governor, Samuelson attracted opposition, receiving the nickname "Dumb Don" from some of his political detractors.[10] Despite having majorities of his own party in both chambers of the state legislature, Samuelson vetoed a record 39 bills sent to him by the legislature.[8]

Primary elections

editPrimary elections were held on Tuesday, August 4, 1970.[11][12]

Republican primary

editIn his bid for re-nomination by the Republican party, Samuelson faced only one challenger: former state senator Dick Smith of Rexburg. Smith had served as chairman of the state Board of Regents, and was known for his support for higher education. He struggled to secure enough support to qualify for the state primary, in part because he received little backing from state party officials. During his primary campaign, Smith vowed to vigorously enforce anti-pollution measures; he also criticized Samuelson for his fiscal policies.[5] Smith received support from education communities. The Idaho State Journal forecast that Samuelson would most likely win the race, writing that "Samuelson has the lead but it's not insurmountable by any means. The odds favor him, is all."[13]

In the August primary, Samuelson secured 46,719 votes, or 58.36 percent of the ballots cast. Smith received 33,339 votes, amounting to 41.64 percent of the ballots cast.[1] Samuelson won in all but 10 of Idaho's 44 counties.[5]

Candidates

edit- Don Samuelson, Sandpoint, incumbent governor

- Dick Smith, Rexburg, former state senator and chairman of Board of Regents

Results

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Don Samuelson (incumbent) | 46,719 | 58.36 | |

| Republican | Dick Smith | 33,339 | 41.64 | |

| Total votes | 80,058 | 100.00 | ||

Democratic primary

editThree candidates competed for the Democratic party's nomination. Andrus was the front-runner and eventual winner, having lost the party's 1966 primary for the nomination to Charles Herdnon by 1.8 percent, or under 2,000 votes.[4] Prior to his 1966 gubernatorial bid, Andrus had served three terms in the state Senate, from 1960 to 1966.[14] Andrus drew support in the Democratic primary largely from the same areas that supported Smith in the Republican primary.[13]

Andrus faced two opponents in the primary: state representative Vernon Ravenscroft of Tuttle (in Gooding County), who campaigned for aid to farmers and against diverting water away from farmers; and Lloyd Walker, a Twin Falls attorney whose campaign promise was the replacement of the state Commissioner of Agriculture.[5][13] Ravenscroft and Andrus were both noted for having strong organizations, while Walker's was perceived as disorganized.[13]

Walker was noted for his aggressive attacks on Andrus, many based on an unsubstantiated claim that Andrus's alleged $25,000 in campaign funds had been largely funded by big businesses. The Idaho State Journal, however, reported that the attacks were false: Andrus's largest campaign contribution was $1,100—just $100 more than Walker's top donation—and that it came not from a business, but from a private citizen. The Journal also argued that the attacks were "getting old" and that his campaign seemed to rely on attacks and publicity stunts to get attention. However, they speculated that, of Ravenscroft and Andrus, it was Ravenscroft who lost more support due to Walker, and that should Walker exit the race, Ravenscroft might be in a much better position to beat Andrus in the primary.[13]

Ravenscroft ran largely on his image of a rural community-friendly candidate: he was quoted in the Idaho State Journal as saying "I'm the only one of the three that's had a shovel in my hands." Ravenscroft was unusually strong in traditionally conservative rural areas.[13]

By the end of the primary season, all three candidates had run out of campaign funds, which most handicapped Ravenscroft and Walker, as they had far less name recognition. The Idaho State Journal gave Andrus the advantage in the primary, writing in their July 31 edition that "The Democrats will probably elect Andrus. Ravenscroft could be close. And Walker could surprise everyone with his total on Aug. 5."[13]

In the August primary, Andrus won with 29,036 votes, or 46.04 percent of the vote. In second place was Ravenscroft, who received 23,369 votes, or 37.05 percent. Walker placed third in the primary, with 10,664 votes and 16.91 percent of the ballots cast.[4]

Candidates

edit- Cecil Andrus, Lewiston state senator and 1966 gubernatorial nominee

- Vernon Ravenscroft, Tuttle state representative

- Lloyd Walker, Twin Falls attorney

Results

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Cecil Andrus | 29,036 | 46.04 | |

| Democratic | Vernon Ravenscroft | 23,369 | 37.05 | |

| Democratic | Lloyd Walker | 10,664 | 16.91 | |

| Total votes | 63,069 | 100.00 | ||

General election

editCampaigning

editFor much of the election campaign, Andrus positioned himself as a moderate centrist. His campaign slogan was "A Governor for ALL Idaho."[15] Though the public paid little attention to the race in its early months, interest in the election picked up in October, as candidates began debating the issues. Taxes, education, and environmental conservation were among the most-discussed topics in the campaign.[5]

By the general election, Samuelson had acquired a poor reputation with voters.[10] He campaigned largely on his record as a fiscal conservative, having vetoed a bill that would repeal a state law blocking local governments from increasing taxes at a progressive rate. Andrus vowed to repeal the law in question if elected, a position favored by public officials in need of more revenue.[5] Andrus also supported establishing a state-funded but locally operated kindergarten program, and argued in favor of instituting a state sales tax to fund education. Samuelson supported education funding and ran campaign ads displaying the increases in education spending during his tenure. However, he opposed instituting a state sales tax, as he had in 1966.[5][13]

Another major issue in the campaign was a proposal to establish an open-pit mine in Idaho's White Clouds wilderness area. Andrus, in addition to Democratic Idaho Senator Frank Church and several Republican congressmen, opposed the mine, and lobbied in favor of establishing White Clouds as a National Park and Recreation Area. Samuelson supported the mine's development, however, pointing to an estimate that it would generate $4 million in revenue for the state. This position increased his popularity in Custer County, where the mine was to open (Samuelson ultimately received over 80% of the county vote in the election); however, it did little to endear him to voters in the state's urban areas, who enjoyed vacationing at White Clouds.[5]

Both campaigns enlisted high-profile speakers to appear on their candidates' behalf. Popular Democratic U.S. Senator Frank Church made many public appearances around the state to support Andrus's candidacy, while Vice President Spiro Agnew appeared in Boise on behalf of Governor Samuelson. However, Agnew's appearance was judged to have little impact outside of Boise and its surrounding communities.[5]

Results

editThe general election for Governor of Idaho (and many other statewide and local offices, including Attorney General, Lieutenant Governor, and Secretary of State, as well as the state's two seats in the House of Representatives) took place on November 3, 1970.[5][6] The election saw some of the highest campaign spending in the state's history as of 1971; however, voter turnout was unusually low, at 67.9 percent (in previous elections, turnout was as high as 84 percent).[5] Fewer votes were cast in the gubernatorial election than in any other such election since 1958.[5]

Andrus won the election with 128,004 votes, or 52.22 percent of the vote, to Governor Samuelson's 117,108 votes, which amounted to 47.78 percent of the votes cast.[6] Both candidates saw increases in raw votes, and in percentages of total votes, thanks in part to the fact that there were no third-party candidates in the 1970 election, while in the 1966 election there had been three, together having received more than 21 percent of the popular vote.[5][16] Andrus's 10,896-vote margin of victory was within 60 votes of Samuelson's 10,842-vote margin over Andrus four years earlier.[17]

The election saw the reversal of some long-standing trends in political allegiances: historically, the state's upper-income urban areas (most notably Boise, Twin Falls, and Idaho Falls) had strongly backed Republican candidates, while lower-income urban and rural areas traditionally supported Democratic candidates. However, in the 1970 election, Samuelson's returns were unusually strong in lower-income areas, but far weaker than expected in upper-income precincts. Conversely, Andrus carried the usually Republican aforementioned urban areas while under-performing in rural areas; he won the election having carried only 15 of the state's 44 counties. Andrus won a majority of the votes in the state's Northern, Southwest, and Southeast regions, while he failed to carry the state's South-Central counties. Andrus lost in every county that contained no cities with more than 1,000 residents; however, he won in three of the five counties containing a city with at least 20,000 residents.[5]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Cecil Andrus | 128,004 | 52.22% | +14.89% | |

| Republican | Don Samuelson (incumbent) | 117,108 | 47.78% | +6.37% | |

| Total votes | 245,112 | 100.0% | N/A | ||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

Analysis

editIt has been posited that the issue of the White Clouds Mountains contributed to Andrus's victory and helped him to carry the normally conservative urban areas of the state, thanks to their residents' vacationing at the mountains and opposing the proposed mine on the land.[5][18][19] However, the election results have also been called a "life-style choice", in favor of Andrus's conservation and education funding, as opposed to Samuelson's fiscal conservatism at the expense of social programs.[5]

Andrus was the first Democrat to win a gubernatorial election in the state in 24 years.[20] His election began the start of 24 consecutive years in which exclusively Democrats served as the state's governor: Andrus served until January 1977, when he was made the U.S. Secretary of the Interior by newly-elected President Jimmy Carter; Andrus was succeeded by John V. Evans, who served for a decade, until January 1987, when Andrus re-assumed the role of Governor by being elected to a third nonconsecutive term.[18][19] Republican Philip Batt's 1994 gubernatorial election victory marked the end of the 24 years of Democratic governors in Idaho; every Idaho governor since has been a Republican.[20][21]

Although Andrus won the election in 1970 by more than 10,000 votes and more than four percentage points, he had minimal coattails: the only other fellow Democrat to win a statewide office was attorney W. Anthony Park, who won his Attorney General election against the incumbent Republican, Robert M. Robson.[5] Both of the state's seats in the U.S. House of Representatives remained in Republican hands, with the first district's Republican candidate winning by more than 21,000 votes (out of 133,258 cast) and the second district's Republican candidate winning by more than 34,000 votes (out of 100,925 cast).[7]

The election's results aligned with those of other gubernatorial elections across the US that year: thirty-five gubernatorial elections took place in 1970, and Democrats' net gain was 11, meaning that they again controlled a majority of the statehouses.[22]

A December 6 story appeared in the Idaho State Journal to discuss the state's newly divided government: although Andrus held the governorship, both the state senate and House of Representatives had heavily Republican majorities. However, the state representatives and senators felt that the difference of party labels would not be a major issue in legislating.[23]

As governor, Andrus was successful in blocking the plans to open the White Clouds Mountains mine.[24] In 2018, the White Cloud Mountains were renamed the "Cecil D. Andrus-White Clouds Wilderness" in honor of Andrus's emphasis on protecting the mountains.[18] Andrus would remain the last gubernatorial candidate from North Idaho until 2018, when state representative Paulette Jordan received the Democratic party's nomination.[25] She lost in the general election to Republican Brad Little.[26]

Ravenscroft went on to join the Republican Party, serve as their state chairman, and run for governor again in 1978, in the GOP primary.[27] He later gained attention for his close involvement in the Sagebrush Rebellion, arguing in favor of limiting the federal government’s control of federal lands in states, including Nevada and Idaho.[28] While serving in the Carter administration, Andrus designated lands in Idaho to be protected, a decision Ravenscroft challenged in court.[29] Ravenscroft also owned a consulting firm which specialized in natural resources, and served as a lobbyist.[28][30] At the firm, he employed future Idaho congresswoman Helen Chenoweth, who in 1998, during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, disclosed that she had carried on a six-year affair with Ravenscroft while he was married.[28]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "ID Governor - R Primary (1970)". Our Campaigns. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ "Air crash kills Idaho candidate for governor". Morning-Record. (Meriden, Connecticut). Associated Press. September 16, 1966. p. 17.

- ^ "Andrus is likely ballot successor". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. September 16, 1966. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d "ID Governor - D Primary (1966)". Our Campaigns. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Dumcombe, Herbert; Martin, Boyd (June 1971). "The 1970 Election in Idaho". The Western Political Quarterly. 24 (2): 292–300. doi:10.2307/446873. JSTOR 446873. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "ID Governor (1970)". Our Campaigns. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Guthrie, Benjamin J.; Jennings, W. Pat (May 1, 1971). Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 3, 1970 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 8–9. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Warbis, Mark. "Ex-Gov. Don Samuelson, dies at 86 of heart attack; Republican began his term as Idaho governor in 1966". The Lewiston Tribute. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Cook, Rhodes (November 5, 2013). America Votes 30: 2011-2012, Election Returns by State. Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 146. ISBN 9781452290171. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Malloy, Chuck. "The days of Andrus, Evans and Democratic rule". Idaho Press. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "GOP primary win handed to Samuelson". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. August 5, 1970. p. 1.

- ^ "Samuelson and Andrus to vie in Idaho finale". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. August 5, 1970. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shelledy, James (July 31, 1970). "Primary Election: Here's How They Should Finish". Idaho State Journal (newspaper). p. 1.

- ^ Butts, Mike. "Cecil Andrus: From 'accidental' politician to Idaho legend". Idaho Press. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ LiCalzi, Jasper (January 2019). Idaho politics and government : culture clash and conflicting values in the Gem State. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-1496210609. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "ID Governor (1966)". Our Campaigns. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Cook, Rhodes (November 5, 2013). America Votes 30: 2011-2012, Election Returns by State - Rhodes Cook. ISBN 9781452290171. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c Barker, Rocky. "Andrus spent his life protecting this iconic Idaho wilderness; now it will carry his name". Idaho Statesman. The McClatchy Company. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Harris, Shelbie. "Cecil Andrus, record 4-time Idaho governor, dies at 85". Idaho State Journal. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Cecil Andrus, Idaho icon, dies at 85". Post-Register. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ "Past Governors (1890 through present)". Idaho Office of the Governor. Office of the Governor. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "1970 Elections: Democrats Gain in House and Governorships". CQ Press: Online Edition. Congressional Quarterly. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Jester, Earle E. (December 6, 1970). "Turnabout in State Capitol: Can Parties Ignore Labels?". Idaho State Journal (newspaper).

- ^ Dick, Jason (March 23, 2018). "Who Is Cecil Andrus?". Roll Call. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ Richert, Kevin (April 23, 2018). "Democratic Candidates Split on Marijuana Legalization". Idaho Ed News. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Idaho Governor Election Results". The New York Times. January 28, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Haynes (October 12, 1980). "The Flint and the Fire of Idaho's Sagebrush Rebellion". Washington Post. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Neiwert, David. "Lives of the Republicans, Part Two". Salon. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Salisbury, David (May 14, 1981). "Who Rules the Eagle's Roost?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Schmidt, William E. (March 21, 1983). "Skeptics in West Hear Case for U.S. Land Sales". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

External links

edit- Idaho Governor election results at OurCampaigns