This article has been translated from a Wikipedia article in another language, and requires proofreading. (August 2022) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2014) |

Zlatopil (Ukrainian: Златопіль), formerly known as Pervomaiskyi[a] until 2024 and Likhachevo or Lykhacheve[b] until 1952, is a city in Lozova Raion, Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine. It is the fourth largest city in the oblast. Zlatopil hosts the administration of Pervomaiskyi urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[2] Population: 28,510 (2022 estimate).[3]

Zlatopil

Златопіль | |

|---|---|

Railway station | |

| Nickname: | |

| Coordinates: 49°23′13″N 36°12′51″E / 49.38694°N 36.21417°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Kharkiv Oblast |

| Raion | Lozova Raion |

| Hromada | Zlatopil urban hromada |

| Founded | 1869 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mykola Baksheev[1] (Fatherland[1]) |

| Area | |

• Total | 30.8 km2 (11.9 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

• Total | 28,510 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 64102-6 |

| Area code | +380-5748 |

| Website | pervom-rada |

| |

The city is known for Khimprom, one of the biggest chemical factories in the former Soviet Union. The city has lush green plots and parks, a cultural center named "DK Khimik" and a stadium also named "Khimik".

History

editIn 1869 a railway was opened, Kursk-Kharkov-Sevastopol at the current location of the modern city.[4] In August of the same year a whistle stop was built 80 kilometres from Kharkov. Trains stopped for water and firewood and the station was named at first named Oleksiivka and later Likhachevo.[4] Likhachov was a landowner-officer sent there by Empress Catherine II.[4] Likhachov estate was near the village Sivash a few kilometres from the railway. Water was supplied from lake Sivash and a water-tower was built.

After the Russian Civil War the (joint) Alekseevskogo, Berekskogo, Upper Bishkinskogo rural Soviets decided to relocate the peasants of these villages to the farm Likhachevo. So in 1924 a settlement was built in Likhachevo which originally was under the jurisdiction of the Upper Bishkinskyi village council. The founders of the village were migrants from the villages of Alexeevka, Bereka, Maslivka, and Upper-Bishkin. They built streets, such as 1 May Street. Agriculture and crafts schools were built, along with a primary school, which both children and adults attended.

In 1927 the village had 13 lots and 56 residents. In 1928, it was already 85 lots. The population increased as workers came to work at the brick and mechanical plant, as well as the mill. In September 1929, on the initiative of activists Tolokneeva and Fedoseenko, a gang was organized in the village. At the suggestion of porters, it was called "May 1" in honor of the international proletarian holiday. In early December 1929 Lihachevsky machine-tractor station was organized (one of the first in the Kharkiv district). Lihachevsky MTS first served 30 collective Alexeevski district.

A local newspaper Znamiya Truda has been published here since October 1930.[5]

According to the Soviet census of 1939, 640 people lived in Likhachevo.

On 20 October 1941 Axis troops occupied Likhachevo. 38 boys and girls were sent to work as slave laborers in Germany. 15 people from the village joined the partisans in Alexeevski district, whose leaders were Secretary of the Communist Party VS Ulyanov and executive committee chairman AG Buznyka.

Likhachevo repeatedly became the site of fierce fighting. During the war, it changed hands four times. On 16 September 1943 troops of the Steppe Front finally returned Likhachevo to Soviet control.

In 1946 a midwifery unit began to operate in the town. In 1948 a hospital was built, employing two doctors and three nurses.

In 1947 a kindergarten was built.

On 25 December 1948 Likhachevo became the center of the Council of Agriculture, who controlled the farm Pervomajskij, Our Way.

In 1950 a high school was built; its enrollment was 824 students and it employed 28 teachers.

On 24[citation needed] June[citation needed] 1952 the settlement Likhachevo was renamed Pervomaiskyi.[4]

In 1974 it was an urban-type settlement with several factories and 19400 people.[6]

In 1991 Pervomaiskyi received the status of a city.[4]

Until 18 July 2020, Pervomaiskyi was incorporated as a city of oblast significance and served as the administrative center of Pervomaiskyi Raion though it did not belong to the raion. In July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Kharkiv Oblast to seven, the city of Pervomaiskyi was merged into Lozova Raion.[7][8]

In 2022 attempts were made twice to rename the city as part of the decommunization derussification campaigns in Ukraine.[9] Local residents chose a new name for this city - Dobrodar.[9] But local city deputies twice did not support the renaming at city council sessions.[9] A third attempt late September 2023 was also unsuccessful with one vote lacking for the quorum.[10] After another failed vote in the local city council on 25 January 2024 the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's national parliament) can decide on the new name of Pervomaiskyi since the Ukrainian derussification law stipulates that the local city council had until 27 January 2024 to rename the itself and after that date the Verkhovna Rada would do it.[4]

On April 3, the Committee on the Organization of State Power, Local Self-government, Regional Development, and Urban Planning in the Verkhovna Rada stated their support for renaming the city to Zlatopil.[11] On 19 September 2024, the Verkhovna Rada voted to rename Pervomaiskyi to Zlatopil.[12]

Transport

editZlatopil is situated on the Pivdenna Zaliznytsia railway line. The railway station here is called "Likhachove," or, in Russian, "Likhachevo". Zlatopil is also a main road hub which links many other cities like Lozova, Merefa, Balakliia and Izium together with the Kharkiv Oblast.

Economy

editZlatopil was planned as a colony for the workers and clerical staff of the Khimprom chemical factory. Until the fall of the USSR in 1992, the city's inhabitants had good earnings, but afterwards, the city's economy collapsed. Many became jobless. However in the late 1990s some private companies moved into Zlatopil.

Education

editThis section needs to be updated. (January 2024) |

Zlatopil originally had just two schools till 1977. Now it has 5 secondary schools; one is Russian-medium, and the rest are Ukrainian-medium. Zlatopil has 6-day-care centres (detski sad), which are all Ukrainian-medium. There is one college offering technical education after 9th Class in many fields like cooking, tractor building, driving, heavy wheel driving, and field fertilizing.

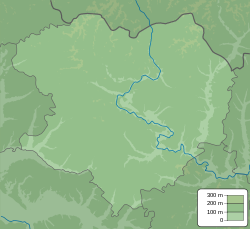

Geography

editAs Zlatopil lies just around 95 km south of Kharkiv, its weather is similar. Zlatopil's climate is moderate continental: cold and snowy winters, and hot summers. The seasonal average temperatures are not too cold in winter, not too hot in summer: −6.9 °C (19.6 °F) in January, and 20.3 °C (68.5 °F) in July. The average rainfall totals 513 mm (20 in) per year, with the most in June and July.

| Climate data for Pervomaiskyi, Kharkiv District, Ukraine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −8.5 (16.7) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.7) |

32 (1.3) |

27 (1.1) |

36 (1.4) |

47 (1.9) |

58 (2.3) |

60 (2.4) |

50 (2.0) |

41 (1.6) |

35 (1.4) |

44 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

549 (21.6) |

| [citation needed] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editAs of the 2001 Ukrainian census, Zlatopil (formerly Pervomaiskiy) had a population of 33,319 inhabitants. The town is home to a large community of people who claim to have an ethnic Russian background. Accounting for almost 38% of the population in 2001, Zlatopil has the second-highest incedence of Russian descendants in any major settlement in the entire Kharkiv Oblast. The exact ethnic composition was as follows:[13]

Gallery

edit-

Former Pervomaiskyi Raion Council

-

Former Pervomaiskyi Raion Court

-

Stand dedicated to honorary citizens

-

Pervomaiskyi Professional Lyceum

-

Zhovtneva Street; Library and Mail Building

Media

editZlatopil has two newspapers working within the region and city, and two private TV channels:

- Pervomaiskyi-Info, a free newspaper publishing advertisements and announcements since 2006

- Nadiya (Nadia) TV, established in 1993

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b (in Ukrainian) "Elections in Kharkiv Region: Kernes' Son in the Regional Council and Local Success "Servants of the People"". The Ukrainian Week. 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Первомайская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Supreme Council will deal with the renaming of Pervomaisky" (in Ukrainian). SQ.com. 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ № 3160. Знамя Труда // Летопись периодических и продолжающихся изданий СССР 1986 - 1990. Часть 2. Газеты. М., «Книжная палата», 1994. стр.413

- ^ Первомайский // Большая Советская Энциклопедия. / под ред. А. М. Прохорова. 3-е изд. том 19. М., «Советская энциклопедия», 1975.

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

- ^ "Pervomaisky failed to rename on the third attempt" (in Ukrainian). SQ.com. 29 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Комітет з питань організації державної влади підтримав перейменування низки населених пунктів, назви яких містять символіку російської імперської політики або не відповідають стандартам державної мови" (in Ukrainian). 4 April 2024.

- ^ Проект Постанови про перейменування окремих населених пунктів та районів [Draft resolution on renaming individual populated places and raions]. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ "Національний склад міст". Datatowel.in.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 25 August 2024.