Zersetzung (pronounced [t͡sɛɐ̯ˈzɛt͡sʊŋ] , German for "decomposition" and "disruption") was a psychological warfare technique used by the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) to repress political opponents in East Germany during the 1970s and 1980s. Zersetzung served to combat alleged and actual dissidents through covert means, using secret methods of abusive control and psychological manipulation to prevent anti-government activities. People were commonly targeted on a pre-emptive and preventive basis, to limit or stop activities of dissent that they may have gone on to perform, and not on the basis of crimes they had actually committed. Zersetzung methods were designed to break down, undermine, and paralyze people behind "a facade of social normality"[3] in a form of "silent repression".[3]

Erich Honecker's succession to Walter Ulbricht as First Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) in May 1971 saw an evolution of "operational procedures" (Operative Vorgänge) conducted by Stasi away from the overt terror of the Ulbricht era towards what came to be known as Zersetzung ("Anwendung von Maßnahmen der Zersetzung"), which was formalized by Directive No. 1/76 on the Development and Revision of Operational Procedures in January 1976.[4] The Stasi used operational psychology and its extensive network of between 170,000[5] and over 500,000[6][7] informal collaborators (inoffizielle Mitarbeiter) to launch personalized psychological attacks against targets to damage their mental health and lower chances of a "hostile action" against the state.[8] Among the collaborators were youths as young as 14 years of age.[9]

The use of Zersetzung is well documented due to Stasi files published after the Berlin Wall fell, with several thousands or up to 10,000 individuals estimated to have become victims,[10][clarification needed] 5,000 of whom sustained irreversible damage.[11][verification needed] Special pensions for restitution have been created for Zersetzung victims.

Definition

editThe Ministry for State Security (German: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, MfS), commonly known as the Stasi, was the main security service of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany or GDR), and defined Zersetzung in its 1985 dictionary of political operatives as

... a method of operation by the Ministry for State Security for an efficacious struggle against subversive activities, particularly in the treatment of operations. With Zersetzung one can influence hostile and negative individuals across different operational political activities, especially the hostile and negative aspects of their dispositions and beliefs, so these are abandoned and changed little by little, and, if applicable, the contradictions and differences between the hostile and negative forces would be laid open, exploited, and reinforced.

The goal of Zersetzung is the fragmentation, paralysis, disorganization, and isolation of the hostile and negative forces, in order to preventatively impede the hostile and negative activities, to largely restrict, or to totally avert them, and if applicable to prepare the ground for a political and ideological reestablishment.

Zersetzung is equally an immediate constitutive element of "operational procedures" and other preventive activities to impede hostile gatherings. The principal force employed to implement Zersetzung are the unofficial collaborators. Zersetzung presupposes information and significant proof of hostile activities planned, prepared, and accomplished as well as anchor points corresponding to measures of Zersetzung.

Zersetzung must be produced on the basis of a root cause analysis of the facts and the exact definition of a concrete goal. Zersetzung must be executed in a uniform and supervised manner; its results must be documented.

The political explosive force of Zersetzung heightens demands regarding the maintenance of secrecy.[12]

The term Zersetzung is generally translated into English as "decomposition", although it can be variously translated as "decay", "corrosion", "undermining", "biodegradation", or "dissolution". The term was first used in a prosecutorial context in Nazi Germany, namely as part of the term Wehrkraftzersetzung (or Zersetzung der Wehrkraft). In Western parlance, Zersetzung can be described as the active application of psychological destabilisation procedures by the State apparatus.

Context and goals

editThe German Democratic Republic (GDR) was established in October 1949 as a socialist state from the Soviet Zone of Occupation, and ruled by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). During its first decade of the GDR's existence, the SED under General Secretary Walter Ulbricht consolidated their rule by overtly combating political opposition, which it subdued primarily through the penal code by accusing them of incitement to war or of calls of boycott and processing them through the regular criminal judiciary.[13] In 1961, to counteract the GDR's practice of isolationism following the construction of the Berlin Wall, the judicial repression was gradually abandoned.[14] At the end of the 1960s, the GDR's desire for international recognition and rapprochement with the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) led to a commitment to adhere to the U.N. Charter.[citation needed]

On 3 May 1971, with the blessing of the USSR's leadership, Erich Honecker became First Secretary of the SED, replacing Ulbricht for an ostensible reason of poor health. Honecker sought to burnish the GDR's international reputation while fighting internal opposition by intensification of the Stasi's efforts to punish dissident behaviors without using the penal code.[15] The GDR signed the Basic Treaty, 1972 with West Germany to respect human rights, or at least announce its intention to do so, and the Helsinki accords in 1975.[16][17][18] Consequently, the SED regime decided to reduce the number of political prisoners, which was compensated for by practising dissident repression without imprisonment or court judgements.[19][20]

British journalist Luke Harding, who had experienced treatment on the part of Russia's FSB in Vladimir Putin's Russia that was similar to Zersetzung, writes in his book:

As applied by the Stasi, Zersetzung is a technique to subvert and undermine an opponent. The aim was to disrupt the target's private or family life so they are unable to continue their "hostile-negative" activities towards the state. Typically, the Stasi would use collaborators to garner details from a victim's private life. They would then devise a strategy to "disintegrate" the target's personal circumstances—their career, their relationship with their spouse, their reputation in the community. They would even seek to alienate them from their children. [...] The security service's goal was to use Zersetzung to "switch off" regime opponents. After months and even years of Zersetzung a victim's domestic problems grew so large, so debilitating, and so psychologically burdensome that they would lose the will to struggle against the East German state. Best of all, the Stasi's role in the victim's personal misfortunes remained tantalisingly hidden. The Stasi operations were carried out in complete operational secrecy. The service acted like an unseen and malevolent god, manipulating the destinies of its victims.

It was in the mid-1970 that Honecker's secret police began to employ these perfidious methods. At that moment the GDR was finally achieving international respectability. [...] Honecker's predecessor, Walter Ulbricht, was an old-fashioned Stalinist thug. He used open terror methods to subdue his post-war population: show trials, mass arrests, camps, torture and the secret police.

But two decades after east Germany had become a communist paradise of workers and peasants, most citizens were acquiescent. When a new group of dissidents began to protest against the regime, Honecker came to the conclusion that different tactics were needed. Mass terror was no longer appropriate and might damage the GDR's international reputation. A cleverer strategy was called for. [...] The most insidious aspect of Zersetzung is that its victims are almost invariably not believed.[21]

In practice

editThe Stasi used Zersetzung essentially as a means of psychological oppression and persecution.[22] Findings of operational psychology[23] were formulated into method at the Stasi's College of Law (Juristische Hochschule der Staatssicherheit, or JHS), and applied to political opponents in an effort to undermine their self-confidence and self-esteem. Operations were designed to intimidate and destabilise them by subjecting them to repeated disappointment, and to socially alienate them by interfering with and disrupting their relationships with others as in social undermining. The aim was to induce personal crises in victims, leaving them too unnerved and psychologically distressed to have the time and energy for anti-government activism.[24] The Stasi intentionally concealed their role as mastermind of the operations.[25][26] Author Jürgen Fuchs was a victim of Zersetzung and wrote about his experience, describing the Stasi's actions as "psychosocial crime", and "an assault on the human soul".[24]

Although its techniques had been established effectively by the late 1950s, Zersetzung was not rigorously defined until the mid-1970s, and only then began to be carried out in a systematic manner in the 1970s and 1980s.[27] It is difficult to determine how many people were targeted, since the sources have been deliberately and considerably redacted; it is known, however, that tactics varied in scope, and that a number of different departments implemented them. Overall there was a ratio of four or five authorised Zersetzung operators for each targeted group, and three for each individual.[28] Some sources indicate that around 5,000 people were "persistently victimised" by Zersetzung.[11] At the College of Legal Studies, the number of dissertations submitted on the subject of Zersetzung was in double figures.[29] It also had a comprehensive 50-page Zersetzung teaching manual, which included numerous examples of its practice.[30]

Units involved

editAlmost all Stasi departments were involved in Zersetzung operations, although first and foremost amongst these was the headquarters of the Stasi's directorate XX (Hauptabteilung XX) in Berlin, and its divisional offices in regional and municipal government. The function of the headquarters and Abteilung XXs was to maintain surveillance of religious communities; cultural and media establishments; alternative political parties; the GDR's many political establishment-affiliated mass social organisations; sport; and education and health services—effectively covering all aspects of civic life.[31] The Stasi made use of the means available to them within, and as a circumstance of, the GDR's closed social system. An established, politically motivated collaborative network (politisch-operatives Zusammenwirken, or POZW) provided them with extensive opportunities for interference in such situations as the sanctioning of professionals and students, expulsion from associations and sports clubs, and occasional arrests by the Volkspolizei[25] (the GDR's quasi-military national police). Refusal of permits for travel to socialist states, or denial of entry at Czechoslovak and Polish border crossings where no visa requirement existed, were also arranged. The various collaborators (Partner des operativen Zusammenwirkens) included branches of regional government, university and professional management, housing administrative bodies, the Sparkasse public savings bank, and in some cases head physicians.[32] The Stasi's Linie III (Observation), Abteilung 26 (Telephone and room surveillance), and M (Postal communications) departments provided essential background information for the designing of Zersetzung techniques, with Abteilung 32 procuring the required technology.[33]

The Stasi collaborated with the secret services of other Eastern Bloc countries to implement Zersetzung. One such example was the Polish secret services co-operating against branches of the Jehovah's Witnesses organisation in the early 1960s,[34] which would come to be known[35] as "innere Zersetzung"[36] (internal subversion).

Use against individuals

editThe Stasi applied Zersetzung before, during, after, or instead of incarcerating the targeted individual. The implementation of Zersetzung—euphemistically called Operativer Vorgang ("operational procedure")—generally did not aim to gather evidence against the target in order to initiate criminal proceedings. Rather, the Stasi considered Zersetzung as a separate measure to be used when official judiciary procedures were undesirable for political reasons, such as the international image of the GDR.[37][38] However, in certain cases, the Stasi did attempt to entrap individuals, as for example in the case of Wolf Biermann: The Stasi set him up with minors, hoping that they could then pursue criminal charges.[39] The crimes targeted for such entrapment were non-political, such as drug possession, trafficking, theft, financial fraud, and rape.[40]

“...the Stasi often used a method which was really diabolic. It was called Zersetzung, and it's described in another guideline. The word is difficult to translate because it means originally "biodegradation." But actually, it's a quite accurate description. The goal was to destroy secretly the self-confidence of people, for example by damaging their reputation, by organizing failures in their work, and by destroying their personal relationships. Considering this, East Germany was a very modern dictatorship. The Stasi didn't try to arrest every dissident. It preferred to paralyze them, and it could do so because it had access to so much personal information and to so many institutions.” —Hubertus Knabe, German historian[41]

Directive 1/76 lists the following as tried and tested forms of Zersetzung, among others:

a systematic degradation of reputation, image, and prestige on the basis of true, verifiable and discrediting information together with untrue, credible, irrefutable, and thus also discrediting information; a systematic engineering of social and professional failures to undermine the self-confidence of individuals; ... engendering of doubts regarding future prospects; engendering of mistrust and mutual suspicion within groups ...; interrupting or impeding the mutual relations within a group in space or time ..., for example by ... assigning geographically distant workplaces.

— Directive No. 1/76 of January 1976 for the development of "operational procedures".[42]

Beginning with intelligence obtained by espionage, the Stasi established "sociograms" and "psychograms" which it applied for the psychological forms of Zersetzung. They exploited personal traits, such as homosexuality, as well as supposed character weaknesses of the targeted individual—for example a professional failure, negligence of parental duties, pornographic interests, divorce, alcoholism, dependence on medications, criminal tendencies, passion for a collection or a game, or contacts with circles of the extreme right—or even the veil of shame from the rumors poured out upon one's circle of acquaintances.[43][44] From the point of view of the Stasi, the measures were the most fruitful when they were applied in connection with a personality; all "schematism" had to be avoided.[43]

Tactics and methods employed under Zersetzung generally involved the disruption of the victim's private or family life. This often included psychological attacks, in a form of gaslighting. Other practices included property damage, sabotage of cars, purposely incorrect medical treatment, smear campaigns including sending falsified compromising photos or documents to the victim's family, denunciation, provocation, psychological warfare, psychological subversion, wiretapping, and bugging.[45]

It has been investigated, but not definitely established, that the Stasi used X-ray devices in a directed and weaponised manner to cause long-term health problems in its opponents.[47] That said, Rudolf Bahro, Gerulf Pannach, and Jürgen Fuchs, three important dissidents who had been imprisoned at the same time, died of cancer within an interval of two years.[46] A study by the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR (Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik or BStU) has meanwhile rejected on the basis of extant documents such as fraudulent use of X-rays, and only mentions isolated and unintentional cases of the harmful use of sources of radiation, for example to mark documents.[48]

In the name of the target, the Stasi made little announcements, ordered products, and made emergency calls, to terrorize them.[49][50] To threaten or intimidate or cause psychoses the Stasi assured itself of access to the target's living quarters and left visible traces of its presence, by adding, removing, and modifying objects such as the socks in one's drawer, or by altering the time that an alarm clock was set to go off.[51][40]

Use against groups and social relations

editThe Stasi manipulated relations of friendship, love, marriage, and family by anonymous letters, telegrams and telephone calls as well as compromising photos, often altered.[52] In this manner, parents and children were supposed to systematically become strangers to one another.[53] To provoke conflicts and extramarital relations the Stasi put in place targeted seductions by Romeo agents.[39] An example of this was the attempted seduction of Ulrike Poppe by Stasi agents who tried to break down her marriage.[54]

For the Zersetzung of groups, it infiltrated them with unofficial collaborators, sometimes minors.[55] The work of opposition groups was hindered by permanent counter-propositions and discord on the part of unofficial collaborators when making decisions.[56] To sow mistrust within the group, the Stasi made believe that certain members were unofficial collaborators; moreover by spreading rumors and manipulated photos,[57] the Stasi feigned indiscretions with unofficial collaborators, or placed members of targeted groups in administrative posts to make others believe that this was a reward for the activity of an unofficial collaborator.[39] They even aroused suspicions regarding certain members of the group by assigning privileges, such as housing or a personal car.[39] Moreover, the imprisonment of only certain members of the group gave birth to suspicions.[56]

Targeted groups

editThe Stasi used Zersetzung tactics both on individuals and groups. There was no particular homogeneous target group, as opposition in the GDR came from a number of different sources. Tactical plans were thus separately adapted to each perceived threat.[60] The Stasi nevertheless defined several main target groups:[25]

- associations of people making collective visa applications for travel abroad

- artists' groups critical of the government

- religious opposition groups

- youth subculture groups

- groups supporting the above (human rights and peace organisations, those assisting illegal departure from the GDR, and expatriate and defector movements).

The Stasi also occasionally used Zersetzung on non-political organisations regarded as undesirable, such as the Watchtower Society of Jehovah Witnesses.[61]

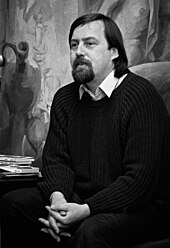

Prominent individuals targeted by Zersetzung operations included Jürgen Fuchs, Gerulf Pannach, Rudolf Bahro, Robert Havemann, Rainer Eppelmann, Reiner Kunze, husband and wife Gerd and Ulrike Poppe, and Wolfgang Templin.

Public awareness and legal aspects

editOnce aware of his own status as a target, GDR opponent Wolfgang Templin tried, with some success, to bring details of the Stasi's Zersetzung activities to the attention of western journalists.[62] In 1977 Der Spiegel published a five-part article series, "Du sollst zerbrechen!" ("You're going to crack!"), by the exiled Jürgen Fuchs, in which he describes the Stasi's "operational psychology". The Stasi tried to discredit Fuchs and the contents of similar articles, publishing in turn claims that he had a paranoid view of its function,[63] and intending that Der Spiegel and other media would assume he was suffering from a persecution complex.[62][64] This, however, was refuted by the official Stasi documents examined after Die Wende (the political power shift in the GDR in 1989–90).

Because the scale and nature of Zersetzung were unknown both to the general population of the GDR and to people abroad, revelations of the Stasi's malicious tactics were met with some degree of disbelief by those affected.[65] Many still nowadays express incomprehension at how the Stasi's collaborators could have participated in such inhuman actions.[65]

Since Zersetzung as a whole, even after 1990, was not deemed to be illegal because of the principle of nulla poena sine lege (no penalty without law), actions against involvement in either its planning or implementation were not enforceable by the courts.[66] Because this specific legal definition of Zersetzung as a crime didn't exist,[67] only individual instances of its tactics could be reported. Acts which even according to GDR law were offences (such as the violation of Briefgeheimnis, the secrecy of correspondence) needed to have been reported to the GDR authorities soon after having been committed in order not to be subject to a statute of limitations clause.[68] Many of the victims experienced the additional complication that the Stasi was not identifiable as the originator in cases of personal injury and misadventure. Official documents in which Zersetzung methods were recorded often had no validity in court, and the Stasi had many files detailing its actual implementation destroyed.[69]

Unless they had been detained for at least 180 days, survivors of Zersetzung operations, in accordance with §17a of a 1990 rehabilitation act (the Strafrechtlichen Rehabilitierungsgesetzes, or StrRehaG), are not eligible for financial compensation. Cases of provable, systematically effected targeting by the Stasi, and resulting in employment-related losses and/or health damage, can be pursued under a law covering settlement of torts (Unrechtsbereinigungsgesetz, or 2. SED-UnBerG) as claims either for occupational rehabilitation or rehabilitation under administrative law. These overturn certain administrative provisions of GDR institutions and affirm their unconstitutionality. This is a condition for the social equalisation payments specified in the Bundesversorgungsgesetz (the war victims relief act of 1950). Equalisation payments of pension damages and for loss of earnings can also be applied for in cases where victimisation continued for at least three years, and where claimants can prove need.[70] The above examples of seeking justice have, however, been hindered by various difficulties victims have experienced, both in providing proof of the Stasi's encroachment into the areas of health, personal assets, education and employment, and in receiving official acknowledgement that the Stasi was responsible for personal damages (including psychological injury) as a direct result of Zersetzung operations.[71]

Use of similar techniques in other countries

editUnder Vladimir Putin, Russia's security and intelligence agencies have been reported to have employed similar techniques against foreign diplomats and journalists in Russia and other ex-USSR states.[72][73]

In 2016, American press reported Zersetzung-like harassment was being carried out by Russia's secret services against U.S. diplomats posted in Moscow as well as in "several other European capitals"; the U.S. government's efforts to raise the issue with the Kremlin were said to have no positive reaction.[74] The Russian Embassy's reply was cited by The Washington Post as implicitly admitting and defending the harassment as a response to what Russia called U.S. provocations and mistreatment of Russian diplomats in the United States.[74] The Russian Foreign Ministry's spokesperson in turn accused the FBI and CIA of provocations and "psychological pressure" vis-à-vis the Russian diplomats.[75]

See also

editLiterature

edit- Annie Ring. After the Stasi: Collaboration and the Struggle for Sovereign Subjectivity in the Writing of German Unification. 280 pages, Bloomsbury Academic (October 22, 2015) ISBN 1472567609.

- Max Hertzberg. Stealing the Future (The East Berlin Series) (Book 1), 242 pages, Wolf Press (August 8, 2015), ISBN 0993324703.

- Josie McLellan. Love in the Time of Communism: Intimacy and Sexuality in the GDR. 250 pages, Cambridge University Press (October 17, 2011), ISBN 0521727618

- Mike Dennis. 'Tackling the enemy- quiet repression and preventive decomposition' in The Stasi Myth and Reality. 269 pages, Pearson Education Limited (2003), ISBN 0582414229

- Sandra Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen. Strategie einer Diktatur. Eine Studie (= Schriftenreihe des Robert-Havemann-Archivs. 8). 3. Auflage. Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft, Berlin (2004), ISBN 3-9804920-7-9.

- Udo Grashoff. 'Zersetzung (GDR)' in Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, Volume 2: Understanding Social and Cultural Complexity, pp. 452–455, UCL Press (2018), ISBN 9781787351899

- Andreas Glaesar. 'Decomposing people and groups' in Political Epistemics: The Secret Police, the Opposition, and the End of East German Socialism. pp. 494–501, University of Chicago, Chicago (2011), ISBN 0226297942

References

edit- ^ Mushaben, Joyce Marie (2023). What Remains?: The Dialectical Identities of Eastern Germans. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 345. ISBN 978-3031188879.

- ^ BBC - World: Europe Dissidents say Stasi gave them cancer , The BBC's Terry Stiastny reports from Berlin, accessed March 18, 2012

- ^ a b Mike Dennis, Norman LaPorte (2011). "The Stasi and Operational Subversion". State and Minorities in Communist East Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-857-45-195-8.

- ^ Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic. Directive No. 1/76 on the Development and Revision of Operational Procedures Richtlinie Nr. 1/76 zur Entwicklung und Bearbeitung Operativer Vorgänge (OV)

- ^ "An Enduring Legacy of a Divided Era (Stasi files) (2001)". The Los Angeles Times. 9 November 2001. p. 86. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Open Stasi files show massive smear campaign - East German police disrupted families, careers(1992)". The Manhattan Mercury. 19 January 1992. p. 5. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Germany ...continued (Stasi files) (1991)". Star Tribune. 15 November 1991. p. 10. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic: The Unofficial Collaborators (IM) of the MfS

- ^ "New book examines communist recruitment of teen informers (Stasi)(1997)". Marysville Journal-Tribune. 2 January 1997. p. 10. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Sonja Süß: Repressive Strukturen in der SBZ/DDR – Analyse von Strategien der Zersetzung durch Staatsorgane der DDR gegenüber Bürgern der DDR. In: Materialien der Enquete-Kommission "Überwindung der Folgen der SED-Diktatur im Prozeß der Deutschen Einheit". (13. Wahlperiode des Deutschen Bundestages). Volume 2: Strukturelle Leistungsfähigkeit des Rechtsstaats Bundesrepublik Deutschland bei der Überwindung der Folgen der SED-Diktatur im Prozeß der deutschen Einheit. Opfer der SED-Diktatur, Elitenwechsel im öffentlichen Dienst, justitielle Aufarbeitung. Part 1. Nomos-Verlags-Gesellschaft u. a. Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6354-1, pp. 193–250.

- ^ a b Consider the written position taken by Michael Beleites, responsible for the files of the Stasi in the Free State of Saxony: PDF[dead link], accessed 24 August 2010, and 3sat : Subtiler Terror – Die Opfer von Stasi-Zersetzungsmethoden, accessed 24 August 2010.

- ^ Ministry for Security of State, Dictionary of political and operational work, entry Zersetzung: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Hrsg.): Wörterbuch zur politisch-operativen Arbeit, 2. Auflage (1985), Stichwort: "Zersetzung“, GVS JHS 001-400/81, p. 464.

- ^ Rainer Schröder: Geschichte des DDR-Rechts: Straf- und Verwaltungsrecht Archived March 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, forum historiae iuris, 6 avril 2004.

- ^ Falco Werkentin: Recht und Justiz im SED-Staat. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn 1998, 2. durchgesehene Auflage 2000, S. 67.

- ^ Sandra Pingel-Schliemann: Zerstörung von Biografien. Zersetzung als Phänomen der Honecker-Ära. In: Eckart Conze/Katharina Gajdukowa/Sigrid Koch-Baumgarten (Hrsg.): Die demokratische Revolution 1989 in der DDR. Köln 2009, S. 78–91.

- ^ Art. 2 des Vertrages über die Grundlagen der Beziehungen zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik vom 21. Dezember 1972. In: Matthias Judt (Hrsg.): DDR-Geschichte in Dokumenten – Beschlüsse, Berichte, interne Materialien und Alltagszeugnisse. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Bd. 350, Bonn 1998, S. 517.

- ^ Art. 1 Abs. 3 UN-Charta. Dokumentiert in: 12. Deutscher Bundestag: Materialien der Enquete-Kommission zur Aufarbeitung von Geschichte und Folgen der SED-Diktatur in Deutschland. Band 4, Frankfurt a. M. 1995, S. 547.

- ^ Konferenz über Sicherheit und Zusammenarbeit in Europa, Schlussakte, Helsinki 1975, S. 11.

- ^ Johannes Raschka: "Staatsverbrechen werden nicht genannt" – Zur Zahl politischer Häftlinge während der Amtszeit Honeckers. In: Deutschlandarchiv. Band 30, Nummer 1, 1997, S. 196

- ^ Jens Raschka: Einschüchterung, Ausgrenzung, Verfolgung – Zur politischen Repression in der Amtszeit Honeckers. Berichte und Studien, Band 14, Dresden 1998, S. 15.

- ^ Harding, Luke (2011). Mafia State: How One Reporter Became an Enemy of the Brutal New Russia. New York: Random House. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0-85265-247-3.

- ^ Klaus-Dietmar Henke: Zur Nutzung und Auswertung der Stasi-Akten. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Nummer 4, 1993, S. 586.

- ^ Süß: Strukturen. S. 229.

- ^ a b Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen. S. 188.

- ^ a b c Jens Gieseke: Mielke-Konzern. S. 192f.

- ^ Pingel-Schliemann: Formen. S. 235.

- ^ Süß: Strukturen. S. 202-204.

- ^ Süß: Strukturen. S. 217.

- ^ Günter Förster: Die Dissertationen an der "Juristischen Hochschule" des MfS. Eine annotierte Bibliographie. BStU, Berlin 1997, Online-Quelle (Memento vom 13. Juli 2009 im Internet Archive).

- ^ Anforderungen und Wege für eine konzentrierte, offensive, rationelle und gesellschaftlich wirksame Vorgangsbearbeitung. Juristische Hochschule Potsdam 1977, BStU, ZA, JHS 24 503.

- ^ Jens Gieseke: Das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit 1950–1989/90 – Ein kurzer historischer Abriss. In: BF informiert. Nr. 21, Berlin 1998, S. 35.

- ^ Hubertus Knabe: Zersetzungsmaßnahmen. In: Karsten Dümmel, Christian Schmitz (Hrsg.): Was war die Stasi? KAS, Zukunftsforum Politik Nr. 43, Sankt Augustin 2002, S. 31, PDF, 646 KB.

- ^ Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen, S. 141–151.

- ^ Dirksen, Hans-Hermann (19 August 2006). "'All over the world Jehovah's Witnesses are the touchstone for the existence of true democracy': Persecution of a religious minority in the German Democratic Republic". Religion, State and Society. 34 (2): 127–143. doi:10.1080/09637490600624808. S2CID 145250719.

- ^ Waldemar Hirch: Zusammenarbeit zwischen dem ostdeutschen und dem polnischen Geheimdienst zum Zweck der "Zersetzung" der Zeugen Jehovas. In: Waldemar Hirch, Martin Jahn, Johannes Wrobel (Hrsg.): Zersetzung einer Religionsgemeinschaft: die geheimdienstliche Bearbeitung der Zeugen Jehovas in der DDR und in Polen. Niedersteinbach 2001, S. 84–95.

- ^ Aus einem Protokoll vom 16. Mai 1963, zit. n. Sebastian Koch: Die Zeugen Jehovas in Ostmittel-, Südost- und Südeuropa: Zum Schicksal einer Religionsgemeinschaft. Berlin 2007, S. 72.

- ^ Richtlinie 1/76 zur Entwicklung und Bearbeitung Operativer Vorgänge vom 1. Januar 1976. Dokumentiert in: David Gill, Ulrich Schröter: Das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit. Anatomie des Mielke-Imperiums. S. 390

- ^ Lehrmaterial der Hochschule des MfS: Anforderungen und Wege für eine konzentrierte, rationelle und gesellschaftlich wirksame Vorgangsbearbeitung. Kapitel 11: Die Anwendung von Maßnahmen der Zersetzung in der Bearbeitung Operativer Vorgänge vom Dezember 1977, BStU, ZA, JHS 24 503, S. 11.

- ^ a b c d Gieseke: Mielke-Konzern. S. 195f.

- ^ a b Pingel-Schliemann: Phänomen. S. 82f.

- ^ Hubertus Knabe: The dark secrets of a surveillance state, TED Salon, Berlin, 2014

- ^ Roger Engelmann, Frank Joestel: Grundsatzdokumente des MfS. In: Klaus-Dietmar Henke, Siegfried Suckut, Thomas Großbölting (Hrsg.): Anatomie der Staatssicherheit: Geschichte, Struktur und Methoden. MfS-Handbuch. Teil V/5, Berlin 2004, S. 287.

- ^ a b Knabe: Zersetzungsmaßnahmen. S. 27–29

- ^ Arbeit der Juristischen Hochschule der Staatssicherheit in Potsdam aus dem Jahr 1978, MDA, MfS, JHS GVS 001-11/78. In: Pingel-Schliemann: Formen. S. 237.

- ^ Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen. S. 266–278.

- ^ a b Der Spiegel 20/1999: In Kopfhöhe ausgerichtet (PDF Archived May 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, 697 KB), S. 42–44.

- ^ Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen, S. 280f.

- ^ Kurzdarstellung Archived July 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine des Berichtes der Projektgruppe "Strahlen" beim BStU zum Thema: "Einsatz von Röntgenstrahlen und radioaktiven Stoffen durch das MfS gegen Oppositionelle – Fiktion oder Realität?", Berlin 2000.

- ^ Udo Scheer: Jürgen Fuchs – Ein literarischer Weg in die Opposition. Berlin 2007, S. 344f.

- ^ Gieseke: Mielke-Konzern. S. 196f.

- ^ "Stasi Tactics – Zersetzung | Max Hertzberg". 22 November 2016.

- ^ Gisela Schütte: Die unsichtbaren Wunden der Stasi-Opfer. In: Die Welt. 2. August 2010, eingesehen am 8. August 2010

- ^ Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen, S. 254–257.

- ^ The New Germany in the East Policy Agendas and Social Developments Since Unification. 2000. p. 186.

- ^ Axel Kintzinger: „Ich kann keinen mehr umarmen“. In: Die Zeit. Nummer 41, 1998.

- ^ a b Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen, S. 358f.

- ^ Stefan Wolle: Die heile Welt der Diktatur. Alltag und Herrschaft in der DDR 1971–1989. Bonn 1999, S. 159.

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). "Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition". The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 112. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ a b Mike Dennis, Norman LaPorte (2011). State and Minorities in Communist East Germany. Berghahn Books. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-857-45-195-8.

- ^ Kollektivdissertation der Juristischen Hochschule der Staatssicherheit in Potsdam. In: Pingel-Schliemann: Zersetzen. S. 119.

- ^ Mike Dennis: Surviving the Stasi: Jehovah's Witnesses in Communist East Germany, 1965 to 1989. In: Religion, State and Society. Band 34, Nummer 2, 2006, S. 145-168

- ^ a b Gieseke: Mielke-Konzern. S. 196f.

- ^ Scheer: Fuchs. S. 347.

- ^ Treffbericht des IMB "J. Herold" mit Oberleutnant Walther vom 25. März 1986 über ein Gespräch mit dem "abgeschöpften" SPIEGEL-Redakteur Ulrich Schwarz. Dok. in Jürgen Fuchs: Magdalena. MfS, Memphisblues, Stasi, Die Firma, VEB Horch & Gauck – Ein Roman. Berlin 1998, S. 145.

- ^ a b Vgl. Interviews mit Sandra Pingel-Schliemann (PDF; 114 kB) und Gisela Freimarck (PDF; 80 kB).

- ^ Interview mit der Bundesbeauftragten für die Stasi-Unterlagen Marianne Birthler im Deutschlandradio Kultur vom 25. April 2006: Birthler: Ex-Stasi-Offiziere wollen Tatsachen verdrehen, eingesehen am 7. August 2010.

- ^ Renate Oschlies: Die Straftat "Zersetzung" kennen die Richter nicht. In: Berliner Zeitung. 8. August 1996.

- ^ Hubertus Knabe: Die Täter sind unter uns – Über das Schönreden der SED-Diktatur. Berlin 2007, S. 100.

- ^ Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk: Stasi konkret – Überwachung und Repression in der DDR, München 2013, S. 211, 302f.

- ^ Stasiopfer.de: Was können zur Zeit sogenannte "Zersetzungsopfer" beantragen?, PDF, 53 KB, eingesehen am 24. August 2010.

- ^ Jörg Siegmund: Die Verbesserung rehabilitierungsrechtlicher Vorschriften – Handlungsbedarf, Lösungskonzepte, Realisierungschancen, Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung, Symposium zur Verbesserung der Unterstützung der Opfer der SED-Diktatur vom 10. Mai 2006, PDF (Memento vom 28. November 2010 im Internet Archive), 105 KB, S. 3, eingesehen am 24. August 2010.

- ^ Russia uses dirty tricks despite U.S. 'reset'

- ^ Russian spy agency targeting western diplomats, The Guardian, 2011-7-23

- ^ a b Rogin, Josh (26 June 2016). "Russia is harassing U.S. diplomats all over Europe". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Захарова: ФБР и ЦРУ постоянно провоцируют российских дипломатов BBC, 28 June 2016.

External links

edit- Hubertus Knabe (historian) The dark secrets of a surveillance state, TED Salon, 19 minutes,· Filmed June 2014, Berlin

German language links

edit- MfS Richtlinie 1/76 zur „Entwicklung und Bearbeitung operativer Vorgänge – Die Anwendung von Maßnahmen der Zersetzung“ www.bstu.bund.de, accessed 14 December 2015

- Der Einsatz von politisch-operativen Zersetzungsmaßnahmen im Rahmen der operativen Vorgangsbearbeitung gegen Erscheinungen des politischen Untergrundes im Verantwortungsbereich der Linie XX/7. Master's thesis Hochschule des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit, Potsdam, demokratie-statt-diktatur.de, by Bundesbeauftragter für die Stasi-Unterlagen

- MfS-Richtlinie 1/76 MfS, DDR-Wissen.de, accessed 14 December 2015

- Dr. Sandra Pingel-Schliemann „Leise Formen der Zerstörung“ havemann-gesellschaft.de, lecture for book publication, 23 May 2002, Berlin

- Stasi-in-Erfurt.de: Zersetzungsmaßnahmen am Beispiel einer Umweltgruppe with many original documents

- Hartmut Holz: Zersetzung: Machtmittel des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit in der ehemaligen DDR Psychiatrische Praxis, thieme-connect.com, doi 10.1055/s-2005-915501 (subscription required)

- DDR-Wissen.de: Zersetzung, accessed 14 December 2015