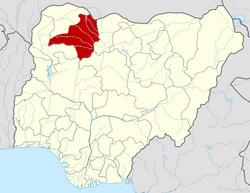

A series of lead poisonings in Zamfara State, Nigeria, led to the deaths of at least 163 people between March and June 2010,[1] including 111 children.[2] Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health figures, state the discovery of 355 cases[1] with 46 percent proving fatal.[3][4] It was one of the many lead poisoning epidemics with low and middle income countries. By 2022, Médecins Sans Frontières stated that conditions had greatly improved after years of a lead poisoning intervention programme.[5]

| |

| Date | March - June 2010 |

|---|---|

| Location | Zamfara State, Nigeria |

| Casualties | |

| 163+ dead | |

| 355 cases discovered | |

Findings

editAn annual immunization programme in Northern Nigeria led to the discovery of a high number of child deaths in the area. [citation needed] An investigation[1] showed that they had been digging for gold at the times of their deaths, in an area where lead is prevalent.[1] It was thought by the villagers that all the children had contracted malaria but Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) found unusually high levels of lead in the blood during tests.[1] The BBC suggested the contamination of water may have contributed to the high mortality rate.[1] Blacksmith Institute (renamed Pure Earth) was called in by the Nigerian authorities to assist in the removal of toxic lead.[citation needed]

It is thought that the poisonings were caused by the illegal extraction of ore by villagers, who take crushed rock home with them to extract.[6] This results in the soil being contaminated from lead which then poisons people through hand-to-mouth contamination.[6] Others have been contaminated by contact with contaminated tools and water.[7]

Actions

editIn an effort to halt the epidemic, the authorities are clamping down on illegal mining and carrying out a clean-up of the area.[6] The number of cases has fallen since April when illegal mining in the area was halted, and some of the residents were evacuated.[7] Education on health and the dangers of lead mining is also being given to local people.[6] It is hoped that the clean-up can be completed prior to the start of the rainy season in July, which will spread contaminants, though it is being hampered by the remoteness of the villages and Muslim restrictions preventing men from entering some compounds.[7][8]

Those who died came from several villages.[1] Five villages in the Local Government Areas of Anka and Bungudu were affected.[2]

Treatment

editTwo treatment camps were established by health authorities to deal with the crisis.[1] The World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the Blacksmith Institute assisted with the epidemic.[2] Federal health ministry epidemiologist Henry Akpan said: "We are working with the state ministry of health to give health education and create enlightenment on the dangers of illegal mining".[2] Nigeria's chief epidemiologist Dr. Henry Akpan announced the discovery of the epidemic on 4 June 2010. Blacksmith has been removing toxic lead from houses and compounds in the villages, so that surviving children returning from treatment will not be re-exposed to toxic lead in their homes.[9] The dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) chelation therapy deployed to 3,180 children by MSF is associated with a substantial reduction in the mortality rate of observed and potential lead poisoning cases.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h "Nigeria – lead poisoning kills 100 children in north". BBC News. BBC. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Lead poisoning kills 163 in Nigeria". Independent Online (South Africa). Independent News & Media. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Yahaya, Sahabi (4 June 2010). "Lead poisoning from mining kills 163 in Nigeria". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 4 June 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Lo, Yi-Chun; Dooyema, Carrie A.; Neri, Antonio; Durant, James; Jefferies, Taran; Medina-Marino, Andrew; Ravello, Lori de; Thoroughman, Douglas; Davis, Lora (2012). "Childhood Lead Poisoning Associated with Gold Ore Processing: a Village-Level Investigation—Zamfara State, Nigeria, October–November 2010". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (10): 1450–1455. doi:10.1289/ehp.1104793. PMC 3491928. PMID 22766030.

- ^ Oluwaseun, Adebowale (11 February 2022). "MSF Says Children No Longer Dying Of Lead Poisoning In Northwest Nigeria". HumAngle. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Lead poisoning kills 163 in Nigeria: health official". AFP. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ a b c "Lead poisoning from mining kills 163 in Nigeria". Reuters. 4 June 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/africa/06/13/nigeria.lead.clean.up/index.html CNN: Lead clean-up in Nigerian village is life-or-death race against time

- ^ "Lead poisoning disaster in Nigeria | PRI's the World". Archived from the original on July 18, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010. Public Radio International's The World, Interview with Blacksmith President Richard Fuller

- ^ Thurtle, Natalie; Greig, Jane; Cooney, Lauren; Amitai, Yona; Ariti, Cono; Brown, Mary Jean; Kosnett, Michael J.; Moussally, Krystel; Sani-Gwarzo, Nasir; Akpan, Henry; Shanks, Leslie; Dargan, Paul I. (7 October 2014). "Description of 3,180 Courses of Chelation with Dimercaptosuccinic Acid in Children ≤5 y with Severe Lead Poisoning in Zamfara, Northern Nigeria: A Retrospective Analysis of Programme Data". PLOS Medicine. 11 (10). Public Library of Science: e1001739. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001739. PMC 4188566. PMID 25291378.