Frank B. Adams (December 19, 1847[1] – December 29, 1929[2]), commonly known as Yank Adams, was a professional carom billiards player who specialized in finger billiards, in which a player directly manipulates the balls with his or her hands, instead of using an implement such as a cue stick,[3] often by twisting the ball between one's thumb and middle finger.[4] Adams, who was sometimes billed as the "Digital Billiard Wonder",[5] has been called the "greatest of all digit billiards players",[6] and the "champion digital billiardist of the World."[7] George F. Slosson, a top billiards player of Adams' era, named him the "greatest exhibition player who ever lived."[6] Adams' exhibitions drew audiences of 1,000 or more, leaving standing room only, even in small venues.[8]

Yank Adams | |

|---|---|

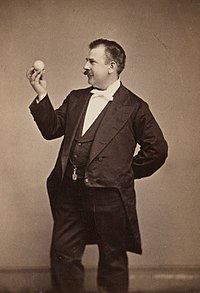

Adams posing with a billiards ball | |

| Born | Frank B. Adams December 14, 1847 |

| Died | December 29, 1929 (aged 82) |

| Other names | Yank Adams The Digital Billiard Wonder |

Adams' career began when he found his aptitude for bowling translated to the playing of billiards. One day when he was 25 years old, he picked up some billiard balls and began to "bowl" on the table and soon discovered he could manipulate the balls with great accuracy in this manner. Largely self-taught, Adams thereafter amassed a large repertoire of finger billiards shots. He engaged a manager and began to give performances, his first was at an engagement in New York City. Later, Adams traveled extensively, giving exhibitions and taking on challengers in cities across the United States and some in Europe. During his travels, Adams performed before the Vanderbilts, the Goulds, three U.S. Presidents, the Prince of Wales in London, and the Comte de Paris in Paris. One of the largest matches ever played of any form of billiards took place at Manhattan's Gilmore's Gardens in 1878. Adams played using his fingers against William Sexton, the reigning cue champion of the world, who used a cue; Adams won the three-day competition in the game of straight rail.

Early life

editAdams was raised in Norwich, Connecticut, which led to him being nicknamed "Yank" later in life.[9] From a young age, he exhibited the substantial hand strength required for finger billiards.[1] When he was less than a year old, he could hurt his mother with his grip; she gave him chunks of bread to squeeze instead.[1] Adams was large for his age, and in 1863, he disguised his youth, and joined the Eighteenth Connecticut Volunteers, with whom he served for three years,[1] fighting for the Union in the American Civil War.[10] After being discharged, Adams worked as a carpenter from 1872 to 1875,[1] and then became a traveling salesman for the American Sterling-Silver Company.[1]

Beginnings in billiards

editAdams finger billiards and exhibition work had its germination in his early bowling interest.[11] By the time he was 17, Adams was an adept bowler; he often gave informal exhibitions of bowling tricks such as "cocked hat", "back frame", and letting the head pin remain standing.[11] In a 1913 interview, Adams said that, "[i]n those days we rolled what was termed 'skew ball', similar to the english put on a cue ball in Billiards."[11]

When Adams was 25 he was employed as a traveling salesman for the Derby Silver Company in New York. One day, while he was waiting for customers in a Poughkeepsie hotel, he strolled into a billiard room, took six pool balls over to a billiard table, and commenced to "bowl".[11] The attention of everyone in the room was attracted by the manner in which Adams made the ball travel.[11] One man asked for the privilege of placing the balls in a certain position for Adams to bowl at; Adams made the shot easily.[11] This started Adams' career as a finger billiard expert. In the next town he traveled to, he hired a table, performed the same stunts with the balls, and added a few new shots.[11] For three months after that Adams practiced various shots each day, and some of the shots he developed during that time became part of his regular exhibition repertoire.[11]

When he returned to New York, Adams met with Maurice Daly, then the "dean of billiards". Daly listened to Adams' story, and said that he was not aware that any startling shots could be accomplished using only the hands.[11] Daly offered Adams a set of four balls,[11] and sat down to watch Adams.[11] After 12 shots, Daly became greatly interested, often asking Adams to repeat shots.[11] At the end of the performance, Daly told Adams that if he ever entertained any idea of entering the billiards field he would give Adams an engagement at his room.[11]

Professional career

editInternational success

editAs Adams became more involved with billiards, he gave up his job with the silver company.[11] Adams went to Sexton's billiard parlor in the Bowery and Sexton employed Adams at Miner's Bowery Theatre at $115 a week.[11] Adams sought to employ a manager as was typical of billiards professionals of the time;[11] he was taken on by Billy O'Brien, a well known sports authority and one-time pugilist[12] who managed Dominick McCaffrey later in his career.[13] O'Brien organized an exhibition tour of the United States for Adams.[12] Three months into the tour, Adams reached Chicago, where he played a three-week engagement for Billy Emmett at $500 a week.[11] After leaving the stage, Adams opened at O'Connor's billiard room, at Fourteenth Street and Fourth Avenue, where he played nightly for a year.[11] Adams then resumed traveling, and gave exhibitions in nearly every city in the United States and a large number of cities in Europe.[11]

In 1868 Adams appeared before the Prince of Wales in London and the Comte de Paris in Paris.[5] While in London, John Roberts, Jr. offered Adams $300 per week for one year to play afternoon and evening at his Argyle Rooms.[5] After playing for the Comte de Paris, the Frenchmen wanted Adams to state his figures for an indefinite period.[5] Adams also played for three Presidents of the United States; while in New York he was paid $100 per night by the Vanderbilt and Gould families.[5] Bullocks Billiard Guide said that Adams had earned more than $70,000 for exhibition alone over seven years, which was more than the combined earnings of all other listed billiardists.[5] Though champion players with cues sometimes dabbled in finger billiards, it was said even of such greats as Jacob Schaefer, George Slosson, and Eugene Carter[5] that "their work, compared with that of the Finger Wonder, is like a novice playing an expert."[5]

Public exhibitions

editAdams' first major public exhibition in New York was held on January 31, 1878, at the Union Square Billiard Rooms before a large audience; he performed there nightly for a week.[16] Reporting on the first night of the event, The New York Times wrote:

The intricacy of the various shots he played, as well as the marvelous accuracy with which they were executed, frequently roused the spectators to an unusual pitch of enthusiasm.... Many of Adams' shots are entirely new, never having been attempted before by any billiards expert. Among them may be mentioned the wonderful "bottle" shot with which last evening's exhibition was brought to a close. Two soda-water bottles were placed at the head of the left-hand rail, about a foot apart, a red ball being placed in the mouth of each bottle. A white ball was next placed against the right-hand rail, directly opposite the lower bottle. Everything being in readiness, Adams then took the remaining white ball in his hand, and masseing upon the ball in the mouth of the upper bottle, jumped his ball to the ball in the mouth of the other bottle, whence, falling upon the table it was carried by a reverse "English" to the middle of the top rail, whence it glided with unerring accuracy to the right-hand rail and caromed upon the first-mentioned white ball, its successful execution being greeted with great applause.[16]

Competitive play and rivalries

editM. Adrian Izar

editPrior to Adams' performances, finger billiards had been demonstrated in New York by French player M. Adrien Izar, who had astonished spectators with an exhibition held on September 20, 1875,[4] before which the game was little known in the United States. In France and England, Izar was considered the game's champion player.[4] The night before his 1878 exhibition, Adams received a telegram in which Izar challenged him to play for the championship and named Chicago as the venue for contest.[16] Adams replied that he was unwilling to leave New York at that time, but that he would pay Izar's expenses to travel to New York.[16] Adams later issued the following statement to newspapers:[17]

I have never intended to play a public match in my line, having never arrogated to myself a superiority above other hand billiard players, although I have deemed myself the equal of any one living in my line, not excepting Mons. Izar, by whom continually letters are written, whose contents have for their purpose a derogation of my skill. That this may be checked, and summarily, I would state that I am willing to play Mons. Izar a match game for $500 a side, in New York City, Boston or Chicago, on a 5x10 table, full size balls and Collender cushion; the championship and gate money to be awarded the player showing the greatest variety of shots in connection with accuracy, and in all giving the most interesting exhibition of finger billiards.[17]

William Sexton

editOn March 15, 1878, a billiards match of straight rail began that lasted three days[18] at the game [19] The match was between Adams and William Sexton, then the cue champion of the world,[11] at Manhattan's Gilmore's Gardens—the predecessor venue of Madison Square Garden.[20] The match pitted Adams' finger billiards against Sexton using a cue,[18] for a purse of $500.[21] The audience was one of the largest that had ever witnessed a billiards game.[11] The terms of the contest stated that on each day of the match, Adams was required to score 2,000 points, while Sexton needed only 1,000.[18]

On the first day of the match, Adams scored 1,110 points using finger billiards.[18] Despite Adams' impressive opening performance, by the third day of the match, Sexton was far in the lead.[11] In Dewey-Defeats-Truman-style, many newspapers reported that Sexton won the tournament, as their reporters left the venue at a time when Sexton had a seemingly indomitable lead and before the match was over.[11] The New York Times, for example, reported that Sexton won the match, though they leavened the result by reporting that despite the prize fund, it was a "friendly match",[19] geared toward exhibition, and that "Adams could undoubtedly have run the game out on three occasions, but preferred to make 'display' shots in place of his usual "nurse" play, against which a cue player stands no chance whatever."[19] However, with Sexton needed only seven points to win the championship, Adams stepped to the table and ran out, making 1,181 points in a row to win the match.[11]

Louis Shaw

editAdams' chief professional rivalry in later years was with Louis Shaw.[22] In 1891 Adams and Shaw disagreed about the format of the finger billiards championship which they would both contest that year. Adams wanted the match to be played for a $500 stake, while Shaw wanted the receipts to be donated to the local firemen's fund.[23]

Other accomplishments

editIn 1879, Adams was chosen to be the official referee for the championship Collender Billiard Tournament held at Tammany Hall. It was contested by top players Marice Daly, Albert Garnier, Eugene Carter, A. P. Rudolphe, Randolph Heiser, William Sexton, George F. Slosson, and "the Wizard", Jacob Schaefer, Sr. at the newly introduced carom billiards discipline called the champion's game,[24][25][26] an intermediary game between straight rail|straight rail and balkine.[3]

In 1889, Adams broke the world record run for successive straight rail points in a match with champion player Jacob Schaefer Sr., in which Adams scored 4,962 counts in a row, which was 2,400 points more than any prior competition high run, albeit with his fingers rather than with a cue.[7] Adams stated in an interview in his later years that his personal high run was 6,900 consecutive straight rail counts.[11]

In 1890, Adams returned to Paris after signing a contract with Eugene Carter to play at Carter's billiard academy for thirteen weeks at 1,000 francs (approximately $200) per week. Afterwards, Adams went in London, under the management of M. Farini, to play at the room of John Roberts, Jr.[27] On a previous trip to London in 1887, Roberts offered Adams £60 a week for six months to give exhibitions, but Adams declined, citing a need to superintend his sporting journal.[27]

Adams was the editor and proprietor of The Chicago Sporting Journal,[28] and the general manager of the New York Sporting and Theatrical Journal.[29] Through his association with the sporting journals, Adams was an intermediary for the issuance of challenge matches, such as boxing bouts. He held the winning stake and distributed the winnings upon the event's conclusion.[30][31][32] Adams owned a number of billiard parlors during his lifetime, including two in Chicago—one named the White Elephant,[6] another called the Academy Billiard Hall,[33] and one on Union Square at 60 East 14th Street in New York City.[6][34] Adams' business cards, in 1877, said, "Yank Adams, champion finger billiardist of the world. Residence immaterial."[28]

Later life

editAdams continued to give exhibitions and was still able to perform well into his later years.[35] For example, the New Rochelle Pioneer newspaper reported that Adams gave an exhibition on December 21, 1915, at 68 years of age, at Chamberlain's Derby Billiard Academy in New Rochelle, New York, and that he was "at his best and made some exceptionally brilliant shots in the presence of 300 lovers of the game. While at the table he kept up a continuous humorous monologue to the great pleasure of his audience."[35] In 1919, when Adans was 71, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that he gave an exhibition before a large audience at Lawler Brothers Billiard Academy of Brooklyn.[36][37]

In 1923, when Adams was 76, the following newspaper story appeared in The Salt Lake Tribune, telling of his whereabouts:[38]

Perhaps you old fellows, too, thought Yank had passed on, but he turned up in New York the other day and is now spending his last days in a Bronx flat. There was a time when Yank Adams was known in every billiard room in America. He was as much at home in Eddie Graney's room at San Francisco as at Tom Foley's in Chicago of Maurice Daly's in New York, and he knew all the billiard players and big and little room keepers from coast to coast. When the history of billiards is written and the names of Willie Hoppe, old and young Jake Schaefer and Welker Cochran are included with others of the great exponents of the indoor sport, there will be a distinct division for one man—the man who did the impossible, who could make the ivories travel the wrong way, or, in the language of the billiard realm, "make 'em talk all languages." That man is Frank B. Adams, known the world over as "Yank" Adams, at one time and even now the world's only finger billiardist who can make all the apparently impossible shots on the table without the aid of a cue. Adams is 76 years old, and after fifty years of exhibitions all over the world has retired from active work to live in the Bronx and conduct a billiard academy of his own at Burnside and Creston avenues in New York with his business manager for the last ten years, Samuel Polakoff. Yank now lives at 635 West 136th street In New York. When I told Tom Foley, the daddy of all the roomkeepers, that Yank Adams was back in the business he laughed and said: "I thought Yank had cashed in. But he's like all those billiard players. They never die."[38]

He died on December 29, 1929, in Manhattan, New York City.[2]

Style of play

editAdams played only with his fingers, disdaining the cue stick entirely.[16] He was known for his skill at finger billiards and for the quickness of his play. In exhibitions it was sometimes advertised that Adams would attempt to make 100 shots in 100 seconds.[39] He would always begin by "feeling out" the cushions on the table, as the speed of the tables varied almost nightly, some fast and some slow.[11]

Adams would sometimes accept challenge matches at his performances.[40] For example, at an exhibition held in Omaha, Nebraska, on November 20, 1889, Adams played against twenty of the best players in the city. Adams manipulated the balls with his fingers, while his opponents used cues and were given a handicap equivalent to a 1,000 point lead.[40]

Adams performed about 80 shots per exhibition. He had a large repertoire of practiced shots—more than 500—affording him the luxury to not having to repeat a single shot during a week-long exhibition. The abundance of shots was unusual, and was described by one sports writer as "more extensive than the entire billiard fraternity put together".[6] The following description of Adams' shots appeared in an 1891 newspaper article, which highlighted them as, "among his difficult feats":

Two quart wine bottles are placed at the short end of the table, three feet apart; a ball is placed on the top of each bottle, and a third ball, six feet from the bottles in the opposite corner. Adams makes the hand ball jump from bottle to bottle then to take an English in space, counting on the third bail, a double shot.

Fifteen balls are placed in a line, three inches apart. On the last ball is placed a piece of chalk, while two feet from the other end, at a square angle, is placed a single ball. Yank drops the hand ball with a Massé twist, which, after hitting the single ball, describes a semi-circle, taken the cushion first, then makes a carrom on the fifteen balls, but is played with such a delicate calculation as barely to reach the last ball; in fact, freezes against it so gently as not to dislodge the chalk previously placed thereon.

A derby hat is placed on the table, under which is a ball. One foot from the hat are two balls a foot apart, which he carroms on, the hand ball continues striking the rim of the hat, forces it up, and goes under making the stroke on the third ball, then returns from under the hat when it rocks the second time.

He also stand at the head of the table, throwing the balls with a hundred-yard force but has them stop eight feet away in such a position as to spell his name.[6]

In an article in the St. Paul Daily Globe, the reporter summed up the events of Adams' exhibition on April 26, 1888:[41]

The great finger billiard exhibition came off last night at the Standard billiard hall to a packed house, and those who saw Yank Adams handle the spheres were more than delighted.... Shot after shot were made in lightning rapidity, spotting the ball, running the whole length of the rail, crossing over, with two cushions and counting, going under hats and in between them, cutting the letter S and making the carom, jump shots, masses and hundreds of others too complicated to put in type. Mr. A.M. Doherty played a game with the exhibitor, and at twenty-eight points left the balls in a scattered position, which were gathered at one shot by Mr. Adams, who made fifty shots in sixty seconds. What seemed his most difficult shot was that of placing fifteen balls in a line, and a piece of chalk on the last ball. The hand ball was then dropped a distance of two feet, described a semi-circle, making a carom on all of the balls and freezing against the last ball. Adams' finger shots discount Schaeffer, Slosson and J. Carter combined.[41]

The public flocked to Adams' exhibitions; often the pool room where he was performing could barely contain the crowd. When Adams performed in Rochester, New York in 1892, the local paper reported that "[n]o man in these broad acres can draw the crowd "Yank" Adams does when an exhibition with the ivories is the card. Last night's crowd was banked up, against the walls, twenty deep in someplaces and many witnessed the exhibition from the table tops and window ledges."[42]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Frank B. Adams" (PDF). The New York Clipper. Vol. 26. August 31, 1878. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ a b "New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949", database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2WGM-FQX : 3 June 2020), Frank B. Adams, 1929.

- ^ a b Shamos, Michael Ian (1993). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York, NY: Lyons & Burford. pp. 46, 94. ISBN 1-55821-219-1.

- ^ a b c "The New Billiard-Player". The New York Times. September 21, 1875. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Finger Billiards: Yank Adams to Give an Exhibition at the Standard To-Night". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. April 26, 1888. p. 5. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "All Done With the Fingers: The Manner in Which Yank Adams Toys With the Spheres". The Sun (New York, NY). June 14, 1891. p. 16. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "Yank Adams, of Chicago". Omaha Daily Bee. November 2, 1889. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Fancy Shots". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. May 1, 1890. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "A Billiard Expert". The New York Times. January 27, 1878. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Evening Post Annual. Hartford, Conn.: Evening Post Association. 1892. OCLC 17937899. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Still Playing Finger Billiards Although Sixty-Seven Years Old" (PDF). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 23, 1913. p. front page. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ a b "Death of Billy O'Brien". The Sun (New York, NY). January 14, 1891. p. 3. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Another Sport Goes Over". The Morning Call (San Francisco). January 20, 1891. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Court Square Theatre". (Direct link unavailable). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 6, 1878. p. front page. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ Brown, Thomas Allston (1902). A history of the New York stage from the first performance in 1732 to 1901. Dodd, Mead and company. p. 217. OCLC 2778331. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "The New Billiard Expert, Mr. "Yank" Adams' First Public Exhibition in This City". The New York Times. January 29, 1878. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Sports and Pastimes: Billiards". (Direct link unavailable). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 28, 1878. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Finger Billiards vs. Cue Billiards". The New York Times. March 16, 1878. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Cue against Finger Billiards". The New York Times. March 17, 1878. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-514049-1.

- ^ "Cue and Finger Billiards". The New York Times. March 17, 1878. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Brooklyn Citizen Almanac. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Citizen. 1893. p. 141. OCLC 12355298.

- ^ "General Sporting Gossip". The Montreal Herald. January 6, 1891. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "Ringing Chimes on the Billiard Balls". The New York Times. November 20, 1879. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "Fine Billiard Playing". The New York Times. November 14, 1879. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "The New Champion's Game" (PDF). The New York Times. November 13, 1879. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "Adams Going to Paris". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. April 24, 1890. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ a b "Big Billiards". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. April 15, 1888. p. 6. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Personal". Omaha Daily Bee. July 4, 1884. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Pat's Chin Music". Omaha Daily Bee. October 21, 1888. p. 8. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Killen Challenges Kilrain". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. August 16, 1888. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "The Myers-Needham Fight to Take Place in Minneapolis Sept. 3". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. September 1, 1888. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Blaisdell Beats Yank Adams" (PDF). The New York Clipper. Vol. 538. November 5, 1881. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "Goulding's New York City Directory". 23. New York: L.G. Goulding. 1877: 1078. OCLC 12683349. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Yank Adams Plays Here" (PDF). New Rochelle Pioneer. December 15, 1915. p. 3. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "Billiards at Lawlers'" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 7, 1919. p. 4. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "Ryan Beats Hanf in Billiard Match". The New York Times. March 29, 1923. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ a b "Famous Finger Billiardist Turns Up in New York" (fee required). The Salt Lake Tribune. February 10, 1923. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Brentano's aquatic monthly and sporting gazetteer. Vol. 4. New York, NY: Brentano's Literary Emporium. 1881. p. 359. OCLC 10081652.

- ^ a b "Yank Adams Nerve". Omaha Daily Bee. November 20, 1889. p. 2. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ a b "Yank's Magic Fingers: Remarkable Billiard Shots By Editor Adams". The Saint Paul Daily Globe. April 27, 1888. p. 5. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Wizard of The Ivories: "Yank" Adams's Exhibition at the Commercial Club" (PDF). Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. February 27, 1892. p. 3. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

External links

editMedia related to Yank Adams at Wikimedia Commons