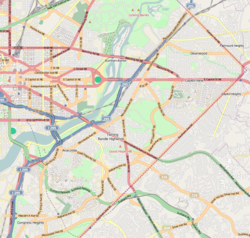

Woodlawn Cemetery is a historic cemetery in the Benning Ridge neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. The 22.5-acre (91,000 m2) cemetery contains approximately 36,000 burials, nearly all of them African Americans. The cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 20, 1996.

| Woodlawn Cemetery | |

|---|---|

View from the front gate | |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1895 |

| Location | 4611 Benning Road SE, Washington, D.C. |

| Country | United States |

| Type | secular and public; closed 1970 |

| Owned by | Woodlawn Cemetery Perpetual Care Association |

| Size | 22.5 acres (91,000 m2) |

| No. of graves | 36,000 |

| Website | www |

| Find a Grave | Woodlawn Cemetery |

Woodlawn Cemetery | |

| Coordinates | 38°53′6″N 76°56′19″W / 38.88500°N 76.93861°W |

| NRHP reference No. | 96001499[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 20, 1996 |

History

editThe District of Columbia was established in 1791, and for the first 160 years of its existence nearly all non-Catholic cemeteries in the city were segregated by race.[2] Many cemeteries refused to bury African Americans, while others separated whites from "colored people" (African Americans, Native Americans, and Asians).[3] By the 1880s, most of the city's African American population lived in the eastern part of the Federal City and Washington County[a] and east of the Anacostia River. Just two cemeteries met the needs of the city's black populace: Graceland Cemetery (what is now Hechninger Mall at the corner of Maryland Avenue NE and Bladensburg Road NE) and Payne's Cemetery (now the site of Fletcher-Johnson Elementary School and the Fletcher-Johnson Recreation Center).[4]

Woodlawn Cemetery was founded because of a crisis among the black burying grounds. Graceland Cemetery, founded in 1871 on the edge of the Federal City, was rapidly engulfed by residential development. By the early 1890s, the decomposition of bodies in the partially filled cemetery was polluting the nearby water supply and creating a health hazard. The Commissioners of the District of Columbia (the city's government) pressed for the closure of Graceland to accommodate the need for housing. With Graceland on the verge of closing, a number of white citizens decided that a new burial ground, much farther from any development, was needed.[5] Woodlawn's incorporators consisted of five white men: Jesse E. Ergood, president; Charles C. Van Horn, secretary-treasurer; and directors Seymour W. Tullock, William Tindall, and Odell S. Smith.[4] They formed the Woodlawn Cemetery Association, and were incorporated on January 8, 1895.[4] A 22.5-acre (91,000 m2) plot of land adjacent to Payne's Cemetery was purchased,[6] a portion of which was the site of the American Civil War's Fort Chaplin.[7] Burial plots were quickly laid out, and Woodlawn Cemetery opened on May 13, 1895.[8]

Between May 14, 1895, and October 7, 1898, nearly 6,000 sets of remains were transferred from Graceland Cemetery to several mass graves at Woodlawn Cemetery.[8] Over the years, the closure of smaller churchyard cemeteries in the Federal City as well as some large burying grounds resulted in more mass graves. The last major transfer occurred from 1939 to 1940, when 139 full and partial sets of remains were relocated to Woodlawn.[9] In all a dozen mass graves eventually came to exist at Woodlawn Cemetery.[10]

Closure, reopening, and current status

editWoodlawn Cemetery remained the preeminent cemetery for the city's African Americans into the 1950s.[5] Nonetheless, records at the site were badly kept, and bodies were often buried in the incorrect plots.[11] Woodlawn was an integrated cemetery, in that it accepted burials of both whites and blacks. Internally, however, it was segregated, with Caucasians being buried in a whites-only section.[12]

As the cemetery filled and space for burial became available in desegregated cemeteries, income from the sale of burial plots dropped significantly. White burials at Woodlawn, once a significant source of income, plummeted after 1912.[12] Lacking a perpetual care trust, the cemetery fell into disrepair. The last burial was made there about 1969,[11] with the total number of dead at the cemetery about 36,000.[12] The Woodlawn Cemetery Association passed into the control of local resident Louis H. Bell and his son Richard Bell in 1961.[11][12] They planned to restore the cemetery by advertising its historic nature and importance to the African American community, and generate income for the restoration. But they discovered that empty sections of the cemetery contained burials. Lacking the funds to fully explore the cemetery and determine which spaces remained free, the Bells abandoned their restoration efforts and the cemetery fell further into disrepair.[11]

In 1967, angry lotholders and their heirs decided to seize control of Woodlawn Cemetery. The group was led by lotholder Willard Wimp; his son-in-law, attorney Emanuel Lipscomb; lotholder Bruce O. Hawkins; and attorney Harry B. Thornton. They incorporated the Woodlawn Cemetery Perpetual Care Association (WCPCA), and sued the Bells. After a five-year legal battle, during which the cemetery association was declared bankrupt and the cemetery ruled to be abandoned, Louis Bell agreed to turn Woodlawn over to the WCPCA in 1972.[13]

With little funds and relying primarily on volunteer help, the WCPCA worked for two decades to restore Woodlawn Cemetery. Reclamation went slowly. When the Washington Metro began laying the route for the Blue Line in the early 1970s, the WCPCA offered to sell the western half of the cemetery to Metro to accommodate the Benning Road station. But Metro declined the offer. Woodlawn reopened for burials in 1975,[14] but by 1987 the cemetery was still decrepit. The WCPCA only raised enough money to pay for a twice-a-year grass and weed cutting.[12] In 1981, the association approved a plan to improve Woodlawn by having more than 5 short tons (4.5 t) of fill dirt delivered to the cemetery. The goal was to use the earth to fill sunken graves and make it easier to maintain the grounds. Lacking funds for labor and equipment, however, a backhoe was used to move the fill dirt. This left a number of headstones buried under as much as 4 feet (1.2 m) of earth, and many others were damaged. The WCPCA acknowledged the situation was unfortunate, but made no plans to uncover the now-buried headstones.[12] Financial problems at Woodlawn continued into the late 1980s. The Washington Post declared the cemetery so choked with weeds in 1987 that it was impassable.[12]

The WCPCA established a five-year fundraising plan in 1987 to put the cemetery on a more even financial footing.[12] Some financial assistance came in the form of a small annual grant from National Harmony Memorial Park, a predominantly African American cemetery in Landover, Maryland. The cemetery received a major boost when Congress appropriated $300,000 in 2000 to help the WCPCA clean up the burying ground. The grant allowed the WCPCA to lease (for $30,000) a ground penetrating radar (GPR) system. Tyrone F. General, president of the WCPCA, was trained for two years in the operation of the GPR system. Beginning in 2009, the WCPCA began scanning the entire cemetery to accurately determine the location of graves—a process that was estimated to take three years.[11]

According to the Internal Revenue Service, the WCPCA's 501(c)(3) charitable status was revoked on May 15, 2013 and reinstated the same day.

In April 2016, a crew of 180 plus volunteers, organized by the U.S.Coast Guard Liaison to Washington D.C, dedicated hours to clearing brush and other debris as part of an effort to restore historically important veteran's cemeteries in the region.[15]

In 2018, members of Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha became involved with the WCPCA.[16]

In popular culture

editWoodlawn, a play about the cemetery, was produced by the Young Playwrights' Theater in 2011.[10]

Notable interments

editThere are many nationally and locally prominent African Americans buried at Woodlawn Cemetery. Among these are eight people for whom local public schools are named.[12]

Richard H. Cain, a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from South Carolina's at-large congressional seat in 1873 was initially buried at Graceland Cemetery in 1887. He may have been moved to Woodlawn Cemetery in 1895, but if so then his grave is unmarked.[17] John Willis Menard of Louisiana, the first African American ever elected to Congress,[b] was also buried at Graceland and later moved to Woodlawn. His grave, however, is marked.[10]

Other notable burials include:

- Amanda Bowen, founder of the Teachers' Benefit and Annuity Association[5]

- Blanche K. Bruce (1841–1898), Republican Senator from Mississippi, and first black Senator to serve a full term in Congress[18]

- Roscoe Conkling Bruce (1879–1950), educator[19]

- Mary P. Burrill (1881–1946), playwright and educator[20]

- Will Marion Cook (1869–1944), composer and violinist[21]

- John Wesley Cromwell (1846–1927), educator, lawyer, and journalist[21][22]

- Wilson Bruce Evans (1824–1898), abolitionist and owner of a major stop on the Underground Railroad, who was involved in the 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue[21]

- John R. Francis (1856–1913), physician and D.C. school board member for whom Francis Junior High School is named[21]

- Marjorie Hill (1886-1910), American educator and founder of Alpha Kappa Alpha [16]

- John Mercer Langston (1829–1897), first Dean of the Howard University School of Law, member of Congress from Virginia's 4th congressional district, and the first president of what is now Virginia State University[21]

- Jesse Lawson (1856–1927), attorney and educator who co-founded and was president of Frelinghuysen University[21]

- Rosetta Lawson (c. 1857–1936) social activist and educator, co-founder of Frelinghuysen University[23]

- Whitefield McKinlay (1852–1941), realtor, banker, collector of the Port of Georgetown, and confidante of Booker T. Washington[5]

- Winfield Scott Montgomery (1853–1928), Professor of Ancient and Modern Languages at Alcorn State University and noted African American physician in Washington, D.C.[21]

- Daniel Alexander Payne Murray (1852–1925), bibliographer, author, politician, historian, and assistant librarian at the Library of Congress[21]

- Sarah Meriwether Nutter (1888-1950), educator and founder of Alpha Kappa Alpha[16]

- Frederick C. Revels (?–1897), Major and Commander, Capital City Guards[24][25]

- Edward A. Savoy (1855–1943), a messenger with the United States Department of State so revered that the Liberty ship USS Edward A. Savoy was named in his honor[26]

- Nelson E. Weatherless (1866–1943), local educator and member, D.C. Board of Examiners (which licensed attorneys in the District of Columbia)[21]

References

edit- Notes

- ^ When initially established, the District of Columbia encompassed a square 10 miles (16 km) on each side. The "Federal City", or "City of Washington", was not at that time expected to fill the entire district, however. To encourage development and the appearance of a thriving urban center, the boundaries of the Federal City were the Potomac River, Rock Creek, Boundary Avenue NW and NE (now Florida Avenue), 15th Street NE, East Capitol Street, and the Anacostia River. Beyond the Federal City was the County of Washington. Georgetown was a distinct entity from both. All three entities merged into a single unified governmental entity in 1908.

- ^ Menard was elected to the House of Representatives to fill the unexpired term of the incumbent in Louisiana's 2nd congressional district. Racist elements in his district challenged his being seated in the House, and he never served.

- Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Richardson, Steven J. "The Burial Grounds of Black Washington: 1880–1919." Records of the Columbia Historical Society. 52 (1989), pp. 304–326

- ^ Richardson 1989, p. 306.

- ^ a b c Sluby 1989, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Gilliam, Dorothy (December 13, 1980). "Are Our Dead Truly Gone and Forgotten?". The Washington Post. pp. B1, B3.

- ^ Sluby 1989, p. 70.

- ^ Simpson, Anne (February 20, 1986). "Cemeteries Give History Lessons: Ex-Policeman Slowly Rebuilds D.C.'s Past". The Washington Post. p. MD5.

- ^ a b Sluby 1989, p. 75.

- ^ Mack & Belcher 2013, pp. 43–45.

- ^ a b c Brown, DeNeen L. (March 6, 2011). "A D.C. Cemetery's Dead Come to Life Again On Stage". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Alcindor, Yamiche (July 30, 2009). "Seeing Where the Bodies Are Buried". The Washington Post. p. DE1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wheeler, Linda (November 16, 1987). "Officials Disagree On Best Way to Save Historic SE Cemetery". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- ^ Beasley, Maurine (March 26, 1973). "'Where Dead Can Lie Until They Arise'". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Richardson 1989, p. 316.

- ^ Pauley, Scott (April 22, 2016). "Volunteers clean up historic Woodlawn Cemetery". Joint Base Journal.

- ^ a b c "Activist strive to preserve historic black cemeteries". 26 September 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Morgan & Taylor 1986, pp. 246–248.

- ^ Bailey, Morgan & Taylor 1986, p. 727.

- ^ Gates & Higginbotham 2009, p. 85.

- ^ "Miss Mary Burrill Dies". The Evening Star. March 15, 1946. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fitzpatrick & Goodwin 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Gunter, Donald W. "John Wesley Cromwell (1846–1927)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Carney, Jessie (2003). Notable Black American Women. Detroit: Gale Research. pp. 399–40. ISBN 978-0810391772.

- ^ Sluby 1989, p. 79.

- ^ "The Colored Guard". The Evening Star. March 28, 1898. p. 11; "Death of Major Revells". The Evening Star. August 27, 1897. p. 2.

- ^ Ford, Sam (February 28, 2011). "Volunteers Fight to Preserve Woodlawn Cemetery". TBD.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

Bibliography

edit- Bailey, N. Louise; Morgan, Mary L.; Taylor, Carolyn R. (1986). Biographical Directory of the South Carolina Senate: 1776–1985. Volume 1. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0872494799.

- Fitzpatrick, Sandra; Goodwin, Maria R. (2001). The Guide to Black Washington: Places and Events of Historical and Cultural Significance in the Nation's Capital. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0781808715.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks (2009). Harlem Renaissance Lives: From the African American National Biography. Cambridge, Mass.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195387957.

- Mack, Mark; Belcher, Mary (May 2013). The Archaeological Investigation of Walter C. Pierce Community Park and Vicinity, 2005–2012: Report to the Public, May 2013 (PDF) (Report). District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation and the District of Columbia Department of Health.

- Richardson, Steven J. (1989). "The Burial Grounds of Black Washington: 1880–1919". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C.: 304–326.

- Sluby, Paul E. Jr. (Spring–Summer 1989). "Woodlawn Cemetery, Washington, D.C.: Brief History and Inscriptions". Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society: 70–100.