Wollaton Hall is an Elizabethan country house of the 1580s standing on a small but prominent hill in Wollaton Park, Nottingham, England. The house is now Nottingham Natural History Museum, with Nottingham Industrial Museum in the outbuildings. The surrounding parkland has a herd of deer, and is regularly used for large-scale outdoor events such as rock concerts, sporting events and festivals.

| Wollaton Hall | |

|---|---|

Wollaton Hall in the snow, November 2010 | |

| Type | Prodigy house |

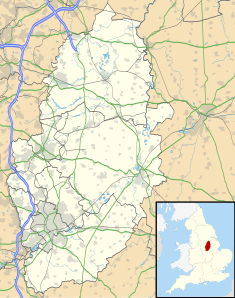

| Location | Nottingham, Nottinghamshire |

| Coordinates | 52°56′53″N 1°12′35″W / 52.9480°N 1.2096°W |

| Built | 1580-1588 |

| Built for | Sir Francis Willoughby |

| Architect | Robert Smythson |

| Architectural style(s) | Elizabethan |

| Owner | Nottingham City Council |

| Website | wollatonhall.org.uk |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Wollaton Hall |

| Designated | 11 August 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1255269 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Camellia House 100 Metres South West of Wollaton Hall |

| Designated | 12 July 1972 |

| Reference no. | 1255271 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Doric Temple and Attached Bridge 200 Metres South-East of Wollaton Hall |

| Designated | 10 August 1989 |

| Reference no. | 1270389 |

| Official name | Wollaton Hall |

| Designated | 1 January 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000344 |

Wollaton and the Willoughbys

editWollaton Hall was built between 1580 and 1588 for Sir Francis Willoughby and is believed to be designed by the Elizabethan architect, Robert Smythson, who had by then completed Longleat, and was to go on to design Hardwick Hall. The general plan of Wollaton is comparable to these, and was widely adopted for other houses, but the exuberant decoration of Wollaton is distinctive, and it is possible that Willoughby played some part in creating it.[1] The style is an advanced Elizabethan with early Jacobean elements.

Wollaton is a classic prodigy house, "the architectural sensation of its age",[2] though its builder was not a leading courtier and its construction stretched the resources he mainly obtained from coalmining; the original family home was at the bottom of the hill. Though much re-modelled inside, the "startlingly bold" exterior remains largely intact.[3]

On 21 June 1603, Willoughby's son Sir Percival Willoughby hosted Anne of Denmark and her children Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth at Wollaton.[4] Charles, later Charles I, came in 1604.[5]

Description

editThe building consists of a central block dominated by a hall three storeys high, with a stone screen at one end and galleries at either end, with the "Prospect Room" above that. From this there are extensive views of the park and surrounding country. There are towers at each corner, projecting out from this top floor. At each corner of the house is a square pavilion of three storeys, with decorative features rising above the roof line. Much of the basement storey is cut from the rock the house sits on.[6]

The floor plan has been said to derive from Serlio's drawing (in Book III of his Five Books of Architecture) of Giuliano da Majano's Villa Poggio Reale near Naples of the late 15th century, with elevations derived from Hans Vredeman de Vries.[7] The architectural historian Mark Girouard has suggested that the design is in fact derived from Nikolaus de Lyra's reconstruction, and Josephus's description, of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem,[8] with a more direct inspiration being the mid-16th century Mount Edgcumbe in Cornwall, which Smythson knew.[9]

The building is of Ancaster stone from Lincolnshire, and is said to have been paid for with coal from the Wollaton pits owned by Willoughby; the labourers were also paid this way. Cassandra Willoughby, Duchess of Chandos recorded in 1702 that the master masons, and some of the statuary, were brought from Italy. The decorative gondola mooring rings carved in stone on the exterior walls offer some evidence of this, as do other architectural features. There are also obvious French and Dutch influences. The exterior and hall have extensive and busy carved decoration, featuring strapwork and a profusion of decorative forms. The window tracery of the upper floors in the central block and the general busyness of the decoration look back to the Middle Ages,[6] and have been described as "fantasy-Gothic".[10]

Later history

editThe house was unused for about four decades before 1687, following a fire in 1642, and then re-occupied and given the first of several campaigns of re-modelling of the interiors.[6] Paintings on the ceilings of the two main staircases and round the walls of one are attributed to Sir James Thornhill and perhaps also Louis Laguerre, carried out around 1700.[6] Re-modelling was carried out by Wyatville in 1801 and continued intermittently until the 1830s.

The hall remains essentially in its original Elizabethan state, with a "fake hammerbeam" wood ceiling of the 1580s, in fact supported by horizontal beams above, but given large and un-needed hammerbeams for decoration.[6] The slightly earlier roofs of the great halls at Theobalds and Longleat were similar.[11]

The gallery of the main hall contains Nottinghamshire's oldest pipe organ, thought to date from the end of the 17th century, possibly by the builder Gerard Smith. It is still blown by hand. Beneath the hall are many cellars and passages, and a well and associated reservoir tank, in which some accounts report that an admiral of the Willoughby family took a daily bath.

The Willoughbys were noted for the number of explorers they produced, most famously Sir Hugh Willoughby who died in the Arctic in 1554 attempting a North East passage to Cathay. Willoughby's Land is named after him.

In 1881, the house was still owned by the head of the Willoughby family, Digby Willoughby, 9th Baron Middleton, but by then it was "too near the smoke and busy activity of a large manufacturing town... now only removed from the borough by a narrow slip of country", so that the previous head of the family, Henry Willoughby, 8th Baron Middleton, had begun to let the house to tenants and in 1881 it was vacant.[12]

The hall was bought by Nottingham Council in 1925. Estate and personal papers of the Willoughby family were used to create the Middleton collection at the department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, The University of Nottingham. They include the Wollaton Antiphonal and the single manuscript holding the 13th-century post-Arthurian romance Le Roman de Silence.[13]

Nottingham Council opened the hall as a museum in 1926. In 2005 it was closed for a two-year refurbishment and re-opened in April 2007. The prospect room at the top of the house, and the kitchens in the basement, were opened up for the public to visit, though this must be done on one of the escorted tours. The latter can be booked on the day, lasts about an hour, and a small charge is made.

In 2011, key scenes from the Batman movie The Dark Knight Rises were filmed outside Wollaton Hall.[14] The Hall was featured as Wayne Manor.[15][16] The Hall is five miles north of Gotham, Nottinghamshire, through which Gotham City indirectly got its name.[17]

Gardens

editWollaton Hall Park is Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[18]

The Camellia House[19] is a listed building in its own right, as are many other buildings and structures,[20] including a doric temple and Ha-Ha.

Owners of Wollaton Hall

edit- 1580–1596: Sir Francis Willoughby (1547–1596)

- 1596–1643: Sir Percival Willoughby

- 1643–1672: Francis Willoughby

- 1672–1729: Thomas Willoughby, 1st Baron Middleton

- 1729–1758: Francis Willoughby, 2nd Baron Middleton

- 1758–1774: Francis Willoughby, 3rd Baron Middleton

- 1774–1781: Thomas Willoughby, 4th Baron Middleton

- 1781–1800: Henry Willoughby, 5th Baron Middleton

- 1800–1835: Henry Willoughby, 6th Baron Middleton

- 1835–1856: Digby Willoughby, 7th Baron Middleton

- 1856–1877: Henry Willoughby, 8th Baron Middleton

- 1877–1922: Digby Wentworth Bayard Willoughby, 9th Baron Middleton

- 1922–1924: Godfrey Ernest Percival Willoughby, 10th Baron Middleton

- 1924–1925: Michael Guy Percival Willoughby, 11th Baron Middleton

- 1925–present: Nottingham Corporation now Nottingham City Council

Similar buildings

editIn 1855, Joseph Paxton designed Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire, which borrows many features from Wollaton. Both properties have been used as film locations for Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy of films, featuring as Wayne Manor – the latter in Batman Begins and Wollaton Hall itself in The Dark Knight Rises.

Nottingham Natural History Museum

editSince Wollaton Hall opened to the public in 1926, it has been home to the city's natural history museum.[21] On display are some of the items from the three quarters of a million specimens that make up its zoology, geology, and botany collections. These are housed in six main galleries:

- Natural Connections Gallery

- Bird Gallery

- Insect Gallery

- Mineral Gallery

- Africa Gallery

- Natural History Matters Gallery

The Museum started life as an interest group at the Nottingham Mechanics' Institution; it is now owned by the Nottingham City Council.

In 2017 the museum hosted a tour of dinosaur skeletons titled Dinosaurs of China, Ground Shakers to Feathered Flyers. The exhibition was attended by over 125,000 people.[22]

From July 2021 to August 2022, the Nottingham Natural History Museum is featuring the world's first exhibit of Titus, a "real" Tyrannosaurus rex fossil which was discovered in Montana, in the United States, in 2014.[23]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Airs, pp. 52-56; Jenkins, p. 581

- ^ Jenkins, p. 581

- ^ Jenkins, p. 581, quoted

- ^ Emily Cole, 'King and Queen in the State Apartment', Le Prince, la Princesse et leurs logis (Picard, 2014), 80: John Nichols, Progresses of James the First, vol. 1 (London, 1828), 170.

- ^ Alice T. Freidman, House and household in Elizabethan England: Wollaton and the Willoughby family (Chicago, 1989), 155, 210.

- ^ a b c d e Historic England. "Wollaton Hall (1255269)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Sir John Summerson (1954) Architecture in Britain, 1530 to 1830. (Pelican History of Art) London: Penguin Books, p31.

- ^ Mark Girouard, "Solomon's Temple in Nottinghamshire" in Town and Country Yale University Press, 1992, pp187-197

- ^ Mark Girouard, Elizabethan Architecture: Its Rise and Fall, 1540–1640 (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art) Yale University Press 2009 p.87

- ^ Airs, p. 52, quoted

- ^ Emily Cole, 'Theobalds, Hertfordshire: The Plan and Interiors of an Elizabethan Country House', Architectural History, 60 (2017), p. 84.

- ^ Leonard Jacks, Wollaton (1881), online at nottshistory.org.uk

- ^ Historical Manuscript Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of Lord Middleton Preserved at Wollaton Hall, Nottinghamshire, compiled by W. H. Stevenson (London:, 1911), pp. 221-36.

- ^ Heath, Neil (16 June 2011). "Batman boost as The Dark Knight Rises at Wollaton Hall". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "The Dark Knight Rises finds new home for Batman in Nottingham". www.metro.co.uk. Associated Newspapers Limited. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "City was paid for Batman filming". This is Nottingham. Northcliffe Media. 30 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Caroline Lowbridge (1 January 2014). "The real Gotham: The village behind the Batman stories". BBC News. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Historic England. "Wollaton Hall (1000344)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Camellia House

- ^ Listed Structures and Buildings

- ^ "Natural History Museum". Archived from the original on 8 April 2010.

- ^ Nottingham Post - Nottingham's Dinosaurs of China Exhibit Closes After Roaringly Successful Summer

- ^ Ingram, Simon (12 May 2021). "'Titus' the T. rex is coming to the UK this summer. Here's why it's a big deal". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

References

edit- Airs, Malcolm, The Buildings of Britain, A Guide and Gazetteer, Tudor and Jacobean, 1982, Barrie & Jenkins (London), ISBN 0091478316

- Jenkins, Simon, England's Thousand Best Houses, 2003, Allen Lane, ISBN 0-7139-9596-3

- Marshall, Pamela (1999), Wollaton Hall and the Willoughby Family, Nottingham Civic Society.

External links

edit- Official website

- Wollaton Hall, by Lady Middleton, from Other famous homes of Great Britain and their stories, edited by A H Malan (Putnam's, 1902), Nottinghamshire History website

- Map and aerial photos

- Photographs of Wollaton Hall from Nottingham21

- Information, photos and slide show of Wollaton Hall & Park from Rise Park Nottingham Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- British Listed Buildings

- Friends of Wollaton Park information on Wollaton Hall