Winthrop is a town in Okanogan County, Washington, United States. It is east of Mazama and north of Twisp. The population was 394 at the 2010 census, and increased to 504 at the 2020 census. Winthrop adopted an Old West theme for its downtown architecture in 1971 to prepare for the opening of the North Cascades Highway.

Winthrop, Washington | |

|---|---|

Downtown Winthrop | |

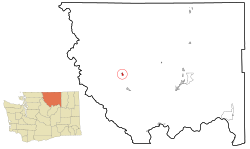

Location of Winthrop, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 48°28′25″N 120°10′44″W / 48.47361°N 120.17889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Okanogan |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.93 sq mi (2.42 km2) |

| • Land | 0.93 sq mi (2.42 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,768 ft (539 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 504 |

| • Density | 540/sq mi (210/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98862 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-79380 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1528259[2] |

| Website | townofwinthrop.com |

History

editNative Americans, including the Methow people, were the first inhabitants of Winthrop, with evidence of human habitation at least 8,000 to 10,000 years before present.[3] They lived along the banks of the Methow, Twisp, and Chewuch rivers, digging camas root, picking berries, fishing, and hunting. Fur trappers visited the valley in the 19th century.[citation needed] The Columbia Reservation was established in 1879 by the federal government for Columbia Plateau tribes under the leadership of Chief Moses, but was eliminated to open the Methow Valley to American settlement on May 1, 1886.[3]

In early 1868, placer gold was discovered in the Slate Creek District.[citation needed] The lure of gold brought the first permanent white settlers to the upper Methow Valley in the 1880s. A settlement, named Winthrop for adventurer and author Theodore Winthrop, was founded and received a post office on June 18, 1891.[3] The town's first trading post and general store was opened in 1892 by Guy Waring of Boston, who moved with his family to the confluence of the Chewuch and Methow rivers a year before. He became the town's postmaster and unsuccessfully attempted to rename the town "Waring" despite local backlash.[3] Waring later formed the Methow Trading Company and established several businesses; his family settled into the "Castle" (now the Shafer Museum).[4]

The town was rebuilt after a devastating fire in 1893.[5] Waring's original Duck Brand Saloon was built in 1891; it survived the fire and is now Winthrop's Town Hall.[citation needed] In 1894, a flood carried away the bridge at the north fork of the river at Winthrop. Colonel Tom Hart rebuilt the bridge in 1895 at Slate Creek. Winthrop's industry at this time consisted of a well-equipped sawmill, several dairies, raising cattle, and supplying the local mines with goods.[6] Owen Wister, Waring's Harvard University roommate, wrote The Virginian, America's first western novel, after honeymooning in Winthrop.[4][5]

Winthrop and the surrounding valley was incorporated into the Washington Forest Reserve by an executive order signed by President Grover Cleveland on February 22, 1897. The order prevented further settlement and development of the valley, but residents protested due to the area's existing use for agriculture; it was modified in 1901 to remove the valley from the protected area.[3] The townsite of Winthrop was formally platted by Waring in 1904; a rival town named Heckendorn was established three years later but was later absorbed into Winthrop when it was incorporated on March 12, 1924.[3][7] By 1915, most of the mines, except for a few in the Slate Creek area, had shut down.[citation needed]

The first plans to build an automobile road across the North Cascades from Bellingham Bay to the Columbia River were approved by the state legislature in 1893.[8] The section through the Methow Valley and Winthrop was completed in 1909 as one of the first highways built by the Washington State Department of Highways and later paved in 1938.[3] Construction of the final 30 miles (48 km) across the mountains did not begin until 1961 and was opened to traffic on September 2, 1972.[9][10] In anticipation of the new highway and the projected tourist traffic through the town, a large-scale remodeling project was approved in 1971 with funding from a lumber magnate and local businesses.[3][11] A two-block section of downtown was rebuilt to use 1890s Old West architecture, including false fronts and a boardwalk; by September 1972, 22 buildings had been remodeled.[12][13] The early design work was contracted to Robert Jorgensen, one of the designers of the Bavarian theme town in Leavenworth, and the project was estimated to cost over $350,000.[3][14] A design review board was established to maintain the architectural theme, enforced by a "Westernization" ordinance.[15]

Geography

editWinthrop lies at the confluence of the Methow and Chewuch rivers in the Methow Valley.[3] The town is in the eastern foothills of the Cascade Mountains at an elevation of 1,760 feet (540 m).[16] The Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest and state-managed Methow Wildlife Area surround the Methow Valley.[17]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has an area of 0.94 square miles (2.43 km2), all land.[18] Winthrop has a lake, Pearrygin Lake, that is a popular swimming hole.

Climate

editLike most of the Inland Northwest, Winthrop has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dsb), with cold, snowy winters and very warm summers with cool nights and little rainfall. Winthrop and Mazama recorded the coldest temperature ever measured in Washington state at –48 °F (–44.4 °C) on December 30, 1968.[19] The hottest temperature recorded in Winthrop was 109 °F (42.8 °C) on June 30, 2021, but frosts can occur even in summer.

| Climate data for Winthrop, Washington, 1991–2020, extremes 1906–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

62 (17) |

79 (26) |

89 (32) |

100 (38) |

109 (43) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

68 (20) |

70 (21) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 43.2 (6.2) |

49.1 (9.5) |

63.4 (17.4) |

75.3 (24.1) |

86.3 (30.2) |

90.6 (32.6) |

97.0 (36.1) |

97.3 (36.3) |

90.2 (32.3) |

76.3 (24.6) |

55.4 (13.0) |

41.4 (5.2) |

98.9 (37.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 29.9 (−1.2) |

38.4 (3.6) |

50.0 (10.0) |

61.1 (16.2) |

71.1 (21.7) |

76.7 (24.8) |

85.8 (29.9) |

85.6 (29.8) |

77.0 (25.0) |

60.9 (16.1) |

41.2 (5.1) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

58.9 (15.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 22.6 (−5.2) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

37.7 (3.2) |

46.7 (8.2) |

55.4 (13.0) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.3 (20.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

59.1 (15.1) |

46.4 (8.0) |

32.9 (0.5) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

45.7 (7.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 15.4 (−9.2) |

18.0 (−7.8) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

32.2 (0.1) |

39.7 (4.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

50.8 (10.4) |

49.3 (9.6) |

41.2 (5.1) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

15.4 (−9.2) |

32.5 (0.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −6.7 (−21.5) |

1.3 (−17.1) |

12.4 (−10.9) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

36.7 (2.6) |

42.1 (5.6) |

39.9 (4.4) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

7.9 (−13.4) |

−2.7 (−19.3) |

−10.4 (−23.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −32 (−36) |

−28 (−33) |

−11 (−24) |

13 (−11) |

20 (−7) |

28 (−2) |

31 (−1) |

28 (−2) |

18 (−8) |

5 (−15) |

−17 (−27) |

−48 (−44) |

−48 (−44) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.06 (52) |

1.28 (33) |

1.23 (31) |

0.84 (21) |

1.13 (29) |

1.09 (28) |

0.69 (18) |

0.45 (11) |

0.45 (11) |

1.37 (35) |

2.03 (52) |

2.57 (65) |

15.19 (386) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 16.6 (42) |

8.8 (22) |

3.4 (8.6) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.1 (2.8) |

7.6 (19) |

21.8 (55) |

59.4 (149.65) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 21.7 (55) |

19.8 (50) |

14.1 (36) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

5.1 (13) |

15.4 (39) |

23.5 (60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.3 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 12.3 | 13.3 | 96.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 10.1 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 4.6 | 11.7 | 34.2 |

| Source 1: NOAA[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 270 | — | |

| 1940 | 365 | 35.2% | |

| 1950 | 396 | 8.5% | |

| 1960 | 359 | −9.3% | |

| 1970 | 371 | 3.3% | |

| 1980 | 413 | 11.3% | |

| 1990 | 302 | −26.9% | |

| 2000 | 349 | 15.6% | |

| 2010 | 394 | 12.9% | |

| 2020 | 504 | 27.9% | |

| Sources: U.S. Decennial Census[22] 2020 Census[23] | |||

As of the 2010 census,[24] there were 394 people, 205 households, and 109 families residing in the town. The population density was 419.1 inhabitants per square mile (161.8/km2). There were 300 housing units at an average density of 319.1 per square mile (123.2/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.5% White, 0.5% African American, 0.3% Asian, 0.8% from other races, and 1.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.3% of the population.

There were 205 households, of which 22.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.0% were married couples living together, 9.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 46.8% were non-families. 43.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.92 and the average family size was 2.59.

The median age in the town was 47.9 years. 17.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 6.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 21.8% were from 25 to 44; 35.4% were from 45 to 64; and 19% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 49.0% male and 51.0% female.

Arts and culture

editAttractions

editWinthrop is known for the American Old West design of all its buildings, making it a tourist destination. The town theme idea was inspired by the example of Leavenworth, Washington, which in turn was heavily based on Solvang, California.[25] Winthrop is a popular cross-country skiing site, with over 120 miles (200K) of groomed trails.[26][27] Events include the Winthrop Rhythm and Blues Festival, and the Methow Valley Chamber Music Festival.[citation needed] Winthrop is home to the oldest legal saloon in Washington state.[28]

References

edit- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Winthrop". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Arksey, Laura (November 11, 2008). "Winthrop — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "Winthrop Chamber". Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Hatcher, Candy (February 9, 2001). "Just about everybody is some sort of activist in this 'Old West with a new age feel'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1.

- ^ "Legacy Washington". Secretary of the State of Washington. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Don (September 14, 2023). "Winthrop begins planning for its official centennial". Methow Valley News. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ "North Cascades Highway marks 20th anniversary". The Seattle Times. September 3, 1992. p. F4.

- ^ Solomon, Chris (August 29, 1997). "Cascades Highway turns 25". The Seattle Times. p. F1.

- ^ Dougherty, Phil (March 20, 2015). "North Cascades Highway opens on September 2, 1972". HistoryLink. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Hill, Bill (June 5, 1971). "Winthrop Going Western on Main Street". Panorama. The Everett Herald. p. 4. Retrieved November 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Town Regresses Happily". The Spokesman-Review. September 2, 1972. p. 20. Retrieved November 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "As tourism marched eastward Winthrop was preparing". The Seattle Times. October 8, 1972. p. 4.

- ^ Herrington, Gregg (August 26, 1973). "Over The Cascades". The Olympian. Associated Press. p. 11. Retrieved November 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nelson, Don (June 27, 2018). "Resignations decimate Winthrop's Westernization Design Review Board". Methow Valley News. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Winthrop Quadrangle (Map). 1:24,000. United States Geological Survey. 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Cantwell, Brian J. (September 24, 2015). "Methow Valley trails safe, open and ready for autumn hikes, winter skiing". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "United States Extreme Record Temperatures & Differences". Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Winthrop 1 WSW, WA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Spokane". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ "Census Bureau profile: Winthrop, Washington". United States Census Bureau. May 2023. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Kirk, Ruth; Carmela Alexander (1990). Exploring Washington's Past: A Road Guide to History. University of Washington Press. pp. 80, 105. ISBN 0-295-97443-5. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ "Winthrop Chamber of Commerce, Things To Do, Winter Recreation, Cross-Country Skiing". Winthrop Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "Sun Mountain Lodge Winter Activities". Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- ^ "Three Fingered Jack's Saloon". 3fingeredjacks.com. Retrieved July 11, 2017.