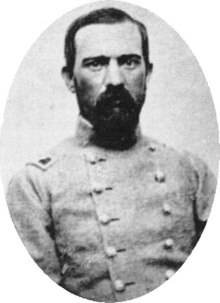

William Dorsey Pender (February 6, 1834 – July 18, 1863) was a general in the Confederacy in the American Civil War serving as a brigade and divisional commander. Promoted to brigadier on the battlefield at Seven Pines by Confederate President Jefferson Davis in person, he fought in the Seven Days Battles and at Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, being wounded in each of these engagements. Lee rated him as one of the most promising of his commanders,[1] promoting him to major general at twenty-nine. Pender was mortally wounded on the second day at Gettysburg.

William Dorsey Pender | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 6, 1834 Edgecombe County, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | July 18, 1863 (aged 29) Staunton, Virginia |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1854–61 (USA) 1861–63 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 3rd North Carolina Infantry 6th North Carolina Infantry Pender's Brigade Pender's Division, III Corps, Army of Northern Virginia |

| Battles / wars | Indian Wars |

| Relations | Robert R. Bridgers (Cousin) Mary Francis "Fanny" Sheppard (Wife) Samuel Turner Pender (Son) William Dorsey Pender, Jr. (Son) David Pender (Brother) |

Early life

editDorsey Pender, as he was known to his friends, was born on February 6, 1834, at Pender's Crossroads, Edgecombe County, North Carolina, to James and Sally Routh Pender, the youngest of four children, with two brothers and a sister. His father was a planter who owned more than 500 acres and 21 slaves in the vicinity of Tarboro, making the family a member of the local elite. Though descended from Virginians, Pender's parents were longtime residents of Edgecombe County. He spent his youth on the farm, hunting, fishing, and riding, before becoming a teenaged clerk in the Tarboro store owned by his older brother, Robert.[2]

He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1854, 19th out of 46 in his class, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery.[3] He served later in the 1st Dragoons (heavy cavalry), where he demonstrated personal bravery in Washington Territory, fighting in the Indian Wars.

Civil War

editOn March 21, 1861, Pender resigned from the U.S. Army and was appointed a captain of artillery in the Confederate States Army. By May he was a colonel in command of the 3rd North Carolina Infantry (also designated the 13th North Carolina) and then the 6th North Carolina. Tried in combat successfully in the Battle of Seven Pines in June 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and command of a brigade of North Carolinians in Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill's Light Division. Confederate President Jefferson Davis personally promoted Pender on the Seven Pines battlefield.

During the Seven Days Battles, Pender was an aggressive brigade commander. He was wounded in the arm at the Battle of Glendale, but recovered quickly enough to rejoin his brigade and fight at Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas (where he received a minor head wound from an exploding shell), Harpers Ferry, and the Battle of Sharpsburg. At Sharpsburg, Pender arrived in the nick of time with A.P. Hill after a 17-mile march to save the Army of Northern Virginia from serious defeat on its right flank.

At Fredericksburg, he was wounded again, in his left arm, but the bone was unbroken, so he continued in command, despite the spectacle of him riding around bleeding. At Chancellorsville, on May 2, 1863, A.P. Hill was wounded in Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's famous march and attack on the flank of the Union XI Corps; Pender assumed command of the division. On the following day, Pender was wounded in the arm yet again, this time a minor injury from a spent bullet that had killed an officer who stood in front of him.

Following the death of Jackson, Gen. Robert E. Lee reorganized his army and promoted A.P. Hill to command the newly formed Third Corps. Pender, at the young age of 29, was promoted to major general and division command. He was well regarded by his superiors. Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis, "Pender is an excellent officer, attentive, industrious and brave; has been conspicuous in every battle, and, I believe, wounded in almost all of them."[4]

Death

editDorsey Pender's promising career ended at the Battle of Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863, his division moved in support of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division down the Chambersburg Pike towards Gettysburg. Heth encountered stronger resistance from the Union I Corps than he expected and was repulsed in his first assault. Uncharacteristically for the normally aggressive Pender, he did not immediately charge in to assist Heth, but took up positions on Herr Ridge and awaited developments. In Heth's second assault of the day, Hill ordered Pender to support Heth, but Heth declined the assistance and Pender once again kept his division in the rear. For the second time in the day, Heth got more than he bargained for in his assault on McPherson's Ridge. He was wounded in action and could not request the assistance from Pender he had earlier refused. Hill ordered Pender to attack the new Union position on Seminary Ridge at about 4 p.m. The 30-minute assault by three of his brigades was very bloody and the brigade of Brig. Gen. Alfred M. Scales was almost completely destroyed by Union artillery canister fire. In the end, Pender's men forced the Union troops back in and through Gettysburg.

On July 2, Pender was posted near the Lutheran Seminary. During the en echelon attack that started with James Longstreet's assault on the right, from the Round Tops through the Peach Orchard, Pender's division was to continue in the attack sequence near Cemetery Hill, to the left of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's attack on Cemetery Ridge. Pender was wounded in the thigh by a shell fragment fired from Cemetery Hill, and turned command over to Brig. Gen. James H. Lane. His division's momentum was broken by the change in command and no effective assault was completed. Pender was evacuated to Staunton, Virginia, where an artery in his leg ruptured on July 18. Surgeons amputated his leg in an attempt to save him, but he died a few hours later.[5]

His superiors wrote in their official reports of the Gettysburg Campaign about Pender's death:

The loss of Major-General Pender is severely felt by the army and the country. He served with this army from the beginning of the war, and took a distinguished part in all its engagements. Wounded on several occasions, he never left his command in action until he received the injury that resulted in his death. His promise and usefulness as an officer were only equaled by the purity and excellence of his private life.[6]

— Robert E. Lee

On this day (July 2, 1863), also, the Confederacy lost the invaluable services of Major General W. D. Pender, wounded by a shell, and since dead. No man fell during this bloody battle of Gettysburg more regretted than he, nor around whose youthful brow were clustered brighter rays of glory.[7]

— A.P. Hill

Legacy

editHe is buried in the graveyard at Calvary Episcopal Church, Tarboro, North Carolina.[8] He is memorialized in the name of Pender County, North Carolina, founded in 1875.[9] He is the posthumous author of The General to his Lady: The Civil War letters of William Dorsey Pender to Fanny Pender, published in 1965.

During World War II, the United States Navy commissioned a Liberty Ship, the SS William D. Pender, in honor of the fallen general.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Tagg, p. 326, quoting Robert E. Lee.

- ^ Wills, pp. 7–10.

- ^ Wills, pp. 19, 20.

- ^ Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXV, Part II, Chap. XXXVII, p. 811

- ^ Tagg, p. 327; Eicher, p. 424.

- ^ Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXVII, Part II, Chap. XXXIX, p. 325

- ^ Official Records, Series I, Vol. XXVII, Part II, Chap. XXXIX, p. 608

- ^ John B. Wells and Sherry I Penney (October 1970). "Calvary Episcopal Church and Churchyard" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved 2014-11-01.

- ^ Proffitt, Martie (Apr 17, 1983). "Local history offers tasty tidbits". Star-News. pp. 8C. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

References

edit- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Longacre, Edward G. General William Dorsey Pender: A Military Biography. Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1580970341.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Wills, Brian Steel, Confederate General William Dorsey Pender. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8071-5299-7

External links

edit- "William Dorsey Pender". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- Pender's papers at the Southern Historical Collection