William Bell (1734/5 - 1794) was an English painter who specialised in portraits. A prize-winning student at the Royal Academy of Arts, influenced by Sir Joshua Reynolds,[1] he achieved eminence in his native area, the North East of England. His best-known works are portraits of Sir John (later Lord) Delaval and his family,[2] which are in the collection of the National Trust at Seaton Delaval Hall, Northumberland. Bell's portrait of Robert Harrison, 1715–1802, is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.[3]

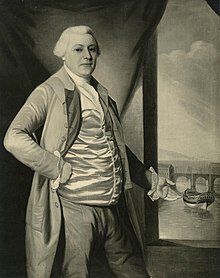

William Bell | |

|---|---|

"Mr Bell" - probably a self-portrait | |

| Born | c1734 Newcastle upon Tyne, England |

| Died | 8 June 1794 Newcastle upon Tyne, England |

| Nationality | British |

Early life

editThe son of a well-regarded bookbinder,[4] Bell was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1734/5. His father, also called William,[5] had at least eleven children; but the only son who certainly survived to adulthood was William.[6] The young William Bell grew up during a period when Newcastle's cultural and intellectual life was flowering. As a young adult, he may have started out as a house-painter,[7] but by the early 1760s, he was established as an artist and married.[8]

Career

editBell's career was assisted by the founding of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. On 30 January 1769, aged 34, he was one of the first six students admitted to the Royal Academy Schools,[9] where promising young artists could work in London under the direction of master painters. In that same year, he entered the annual competition run by the Academy.[10] His picture did not win, but he tried again in 1771 and was awarded a gold medal, which was presented to him by Sir Joshua Reynolds, the president of the Academy. The Newcastle Courant of Saturday 4 January 1772 reported his success thus: “We hear from London that Mr William Bell, son of Mr William Bell, Bookbinder of this town, has had the honour of receiving his Majesty's premium of a gold medal, value 20l, at the Royal Academy, for the best composition and painted historical picture; the subject Venus intreating Vulcan to forge the armour of Aeneas.”

No student of the Royal Academy, having won one of its medals, was permitted to enter the same competition again. Hence further prizes had to be sought from other institutions. In 1772, Bell was awarded 20 guineas for "best historical painting" by the Society of Arts,[11][12] which had been offering such prizes since 1754.

While he was studying in London, Bell spent periods in his home area, painting for Sir John Delaval. His most significant project was a series of portraits. The earliest (in 1770) were of Lady Susanna Delaval, Sir John's wife, and their two eldest children, John and Sophia. In the following year, daughters Frances and Sarah were depicted together. Later, in 1774, Bell painted portraits of Sir John and his daughter Elizabeth, thus completing a full family set. All the portraits were life size and full length, for display in the entrance hall of Seaton Delaval Hall,[13] the Delavals’ principal residence, ten miles from Newcastle.

During the following two years, Bell exhibited paintings in London. In 1775, the Royal Academy showed a pair of pictures, depicting Seaton Delaval Hall from the north and the south, and the following year the Free Society of Artists exhibited Susanna and the Two Elders.[14][15] Like Bell's earlier prize-winning works, this was a large historical picture. It was the last that he painted in London.

For the next eighteen years until his death, Bell based himself permanently in the North East of England and specialised in intimate portraits, limiting his work to local commissions. His sitters included a number of distinguished people: Thomas Bewick, the engraver, "in the style of Rembrandt";[16] Joseph Austin, the actor-manager of the Newcastle Playhouse;[14] Robert Harrison, the mathematician and linguist;[17][18] Francis Peacock, Grand Master of the St. John Masonic Lodge, Newcastle;[19] and John,[20] the son and heir of Newcastle's most gifted goldsmith, John Langlands, who was a generous benefactor to the city.[21] Bell was painting successfully into the 1790s, and died on 8 June 1794 in the Newcastle Infirmary, aged 60.[12] He was buried on 10 June, at St Andrew's Church, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Association with the Delaval Family

editA crucial influence in Bell's life was the patronage offered by Sir John Delaval. Delaval was a successful businessman, whose family owned several country estates (Ford and Seaton Delaval in Northumberland; Doddington in Lincolnshire) and leased a residence in central London (Grosvenor House). For a considerable period of the 18th century, the family engaged artists to produce portraits and tutor young Delavals (some of whom were quite gifted at art);[22] among these artists was Bell, who formed a particularly strong connection with the family.

Bell was the beneficiary of John Delaval's fondness for projects. After Delaval was made a baronet in 1761, this took the form of showcasing his growing wealth and prestige by upgrading his properties. He added to the array of family portraits at Doddington Hall, employing prestigious painters such as Joshua Reynolds.[23] Then, at the end of the 1760s, he turned his attention to Seaton Delaval Hall and employed William Bell to help him realise his plans. John Delaval was sufficiently impressed with Bell's work to offer him an annual income of £50 (about £9000 in today's money) and a cottage to live in.[4] Bell thus effectively became Delaval's staff artist,[24] painting on a grand scale and acting as drawing master for his children.[25] A significant further benefit for Bell was that, when he was studying and painting in London, he was able to live at Grosvenor House, the Delavals’ metropolitan residence.[14]

This patronage, coupled with Bell's studentship at the Royal Academy, led to a somewhat itinerant existence for several years, lodging as necessary in London but returning regularly to his own cottage, 300 miles away in Northumberland. Initially he lived in a property right next to Seaton Delaval Hall; by 1777, he was at Fountain Head, a small clutch of properties within walking distance of the Hall, on the bank leading down to the sea. In this rural setting, his wife Elizabeth had three children: Elizabeth (born 1773), Frances (born 1775) and Sarah Ann (born 1777); and here the family put down roots.

Bell became well known in the community and was eventually regarded as something of a dignitary, "Mr. Bell."[26] Famously he had used several local people as models for figures in his award-winning painting in 1771. Most strikingly, Vulcan, the forger of armour, was based on the blacksmith, Willie Carr. At 6 feet 4 inches tall and weighing 24 stones, he was renowned for his great strength. Carr and Bell were both on good enough terms with Sir John Delaval to be his dinner guests.[27]

Retreat from London

editBell's career reached a turning point in about 1775. By the end of his studentship at the Royal Academy (assuming that it lasted a typical six years), he had made less of a mark in London than several of his peers: he had not exhibited many pictures at the Academy, nor had he been elected one of their Associates. His options for further advancement were to take up an offer from Sir Joshua Reynolds to become one of his regular assistant artists painting draperies,[4] to aim for independence, or to rely on continuing patronage.

He chose the last of those options. However, it was not without complications, because his patron, Sir John Delaval, was soon precipitated into a rather turbulent period. In July 1775, Delaval's only son, Jack, died suddenly at the age of 19, and thus ended the squire's hope of passing on his estates to an heir. Then, by the end of the year, a long-running family dispute over property left Sir John angry with a brother who lived in London. This seems to have made it less comfortable for Bell to stay at his patron's residence, while in the capital. During the exhibition season of 1776, Bell lodged “At Mr. Thickbroom, Organ Builder, New Round Court, Strand”,[14] and thereafter he made no further effort to pursue a career in London.

Bell returned to his cottage in Northumberland, and remained in the employ of Sir John Delaval, without (as far as is known) producing any further major works for Seaton Delaval Hall. However he (Bell) produced two paintings for the St. John Masonic Lodge, Newcastle, which opened in 1777.[19] Since Sir John Delaval was an influential freemason, it is likely that he had a hand in this commission.

In late 1778, Bell oversaw the preparation of two engravings for William Hutchinson's book, A View of Northumberland. This illustrated guide to stately homes included a eulogistic description of "the seat of Sir John Delaval", accompanied by two views of the Hall, based on the oil paintings that Bell had exhibited in London in 1775.

During the following two years, Bell remained on the staff of Seaton Delaval Hall. There is no trace of any work from this period.

Second Period in Newcastle

editDuring 1781 or early 1782, Bell moved to Newcastle. This followed his father's death in 1780,[28] and his decision to set up his business as a portrait painter may well have been made possible by receiving an inheritance.[29]

Also establishing himself in Newcastle at this time was Thomas Bewick, the engraver, who formed a friendship with Bell. Bewick would later write in his memoirs that he was “long acquainted with Wm Bell, Portrait painter &c he was, as a painter, accounted eminent in that profession.”[30] To know Bewick was to belong to a wide social circle, which also included Joseph Bell (not known to be a relative of William), who had established a business in Newcastle as a painter and decorator in 1768, and then in 1778 moved to bigger premises in a yard next to the Nun Gate on Newgate Street, where his business thrived.[31] When William Bell arrived in Newcastle, he chose to work at the same address,[32] and probably used Joseph as his supplier of paints.

William Bell's premises were in an attractive part of town, which housed a host of skilled tradesmen, vendors and professionals. He conducted business from his studio in Newgate Street until at least 1793,[33] and probably for the rest of his life. During that time, he developed his style of rather less formal portraits. However, painting portraits never proved hugely lucrative, and he supplemented his income in several ways.

Firstly, he taught drawing. This was done at a separate Newcastle address, the Back Row,[4] although that fact was not advertised in the local trade directory, where he was listed as a portrait painter and teacher of drawing at the same address.

Secondly, he copied paintings. One example is a commission in 1788 from John (now Lord) Delaval to produce small-scale versions of some of the family portraits that Bell had painted years earlier for Seaton Delaval Hall. The copies are mentioned in a letter written to Delaval at his London address by his manager in the North East: "Last Wednesday the bottle sloop Good Intent sailed, and has on board 14 pairs of young pigeons in 2 cages, and two small whole-length pictures that Mr. Bell was painting when your lordship was down; the other of Mrs. Jadis[34] which he had into Newcastle to copy is not done that I hear of, as he was to let me know when it was finished, to be sent with the others."[35] It is interesting to note that, although no longer on the pay-roll of Seaton Delaval Hall, Bell was still being given occasional work by Lord Delaval.

Thirdly, Bell restored pictures. This may not have been a regular occupation, but it is on record that after a fire in Newcastle's Guildhall in 1791 he repaired portraits of King Charles II and James II.[36]

Bell ended his life well respected in his home area. The medal he had won in 1771 became a renowned trophy in Newcastle, as indicated by the detailed eye-witness description of it given in 1789 by John Brand, a local historian.[37] It weighed, he said, about four ounces. On one side was the head of King George III, on the other a representation of Minerva directing a youth to the Temple of Fame, accompanied by the motto “Haud facilem esse viam volvit.” Under that was the awarding body: “R. Ac. Instituted 1768”. Inscribed around the edge was the credit: “To William Bell, for the best historical picture, 1771.”

Four days after Bell's death in 1794, the Newcastle Courant (14 June) carried this tribute: "DIED, Sunday morning, Mr William Bell, an eminent Portrait Painter, whose memory will be esteemed as long as his animated productions remain, many of which bear testimony to his abilities in this part of the kingdom".

A generation later, an assessment of Bell's final period in Newcastle was offered by Eneas Mackenzie, a local historian, who wrote that Bell was “but indifferently supported, though his portraits were extremely accurate and beautifully finished.” [4]

Works by William Bell

editBell's known paintings are listed below, as far as possible in chronological order. An asterisk indicates a work whose present whereabouts are unknown. Most of the paintings are also mentioned in the sections above, and some are included in the gallery below.

Two Children and a Lamb* In the collection of the Ehrich Galleries, New York (now closed) in 1921. Monochrome reproduction held by National Gallery of Art, Washington, and Courtauld Institute, London.

Time discovering Truth, with two other figures of Envy and Detraction* Entered for Royal Academy's first competition, 1769.[38]

Lady Susanna Delaval (1730-1783) Signed and dated 1770. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276760), open to the public.

John Delaval (1756-1775) Signed and dated 1770. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276756), open to the public.

Sophia Delaval (1755-1793) Signed and dated 1770. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276754), open to the public.

Mr. Holmes* c1771 Referred to in a letter by James Northcote.[7]

Mrs. Holmes* c1771 Referred to in a letter by James Northcote.[7]

Venus Entreating Vulcan to Make Armour for Aeneas* Painted for Royal Academy competition, 1771. Won gold medal.

Frances Delaval (1759-1839) and Sarah Delaval (1763-1800) Signed and dated 1771. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276758), open to the public.

Historical painting (subject unknown)* Painted for Society of Arts competition, 1772. Won 20 guineas for best historical painting.

Two views of Seaton Delaval Hall Attributed to "Mr. Bell" and dated September and October 1773. In Duke of Northumberland's collection. [1][2]

Two views of Ford Castle Attributed to "Mr. Bell", undated. In Duke of Northumberland's collection. [3][4]

Elizabeth Delaval (1757-1785) Signed and dated 1774. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276766), open to the public.

Sir John Hussey Delaval (1728-1808) Signed and dated 1774. In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276762), open to the public.

Two views of Seaton Delaval Hall Exhibited by the Royal Academy, 1775. Almost certainly those in the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276814 & 1276816), but not signed or dated. Based on watercolour sketches of 1773.

Susanna and the Two Elders*. Exhibited by the Free Society of Artists, 1776.

Francis Peacock, Masonic Grand Master* Painted for the new St. John's Lodge in Newcastle upon Tyne, which opened in 1777. Attributed simply to "Bell".[19]

Saint John* Painted for the new St. John's Lodge in Newcastle upon Tyne, which opened in 1777. Attributed simply to "Bell".[19]

Unnamed Gentleman* Signed but not dated. Up for auction at Sotheby's 12 February 1998. Full-colour reproduction from sale catalogue on file at Heinz Archive of National Portrait Gallery, London.

Unnamed Lady* Signed and dated 1782. Sold in Los Angeles, 16 March 1981. Monochrome reproduction on file at Heinz Archive of National Portrait Gallery, London.

John Langlands (1773-1804)* Signed and dated 1782. Sold at the Palais Dorotheum, Vienna, in 2013, from the collection of Lady King of Wartnaby. Sale catalogue online at https://www.dorotheum.com/en/l/5440386/

Mr. Bell* Signed and dated 1785. Probably (but not certainly) a self-portrait. In the collection of the Ehrich Galleries, New York (now closed) in 1921. Monochrome reproduction held by National Gallery of Art, Washington, and Courtauld Institute, London.

Sir John Hussey Delaval (1728-1808) In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276897), open to the public. Presumed to be a copy by Bell of his larger 1774 portrait.

John Delaval (1756-1775) In the collection at Seaton Delaval Hall (NT 1276895), open to the public. Presumed to be a copy by Bell of his larger 1770 portrait.

Sophia Jadis, nee Delaval (1752-1793)* Painted 1788. A copy by Bell of another painting (his own?), commissioned by the subject's father, Lord John Delaval. Referred to in a letter of 11 May 1788.

Joseph Austin (c1740-1821)* Signed and dated 1788. Sold at auction, Christie’s, 25 Nov 1960, from the collection of the late Lord Wigram, as a pair with the following item. Monochrome reproduction on file at Heinz Archive of National Portrait Gallery, London. Provenance reviewed in The Connoisseur, Vol. LIX, Jan-Apr 1921, p205. https://archive.org/details/connoisseurillus59lond/page/206/mode/2up (Includes reproduction.)

Eleanor Austin (1757-1800), wife of Joseph* Signed and dated, but not clearly legible; probably c 1788. Details otherwise as for portrait of her husband.

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828)* Once in possession of William Bewick, and described in letters to his friend T H Cromek, 16 April 1864 & 25 March 1865.

William Potter (1747-1839) In a private collection. Inscriptions on canvas only partly legible, but coupled with style and technique suggest probably by Bell, c1790.

Robert Harrison (1715-1802) Not signed or dated, but label on stretcher identifies artist as Wm Bell and date as 1791. In collection of National Portrait Gallery, London, but only viewable by specific arrangement.

Gallery

editReferences

edit- ^ "William Bell". Royal Academy.

- ^ 11 artworks by or after William Bell, Art UK: see extended Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists biography, under "artist profile". Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- ^ "National Portrait Gallery - Person - William Bell". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Mackenzie, Eneas, A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Town and County of Newcastle upon Tyne, Vol. 1, 1827, p576.

- ^ Newcastle Courant, 4 January 1772

- ^ The register of All Saints Church, Newcastle upon Tyne, records the burial of nine infants, children of "William Bell, Bookbinder," between 1744 and 1768.

- ^ a b c Whitley, William (1928). Artists and Their Friends in England, Vol. 2. Medici Society. p. 287.

- ^ This is known from an infant's baptism record: "William, son of William Bell, Limner," at All Saints Church, Newcastle, on 21 April 1765.

- ^ Nisbet, A. (2004). "Bell, William (1734/5–1806?)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2032. Retrieved 2 October 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Edwards, Edward, Anecdotes of Painters Who Have Resided or Been Born in England, With Critical Remarks on Their Productions, 1808, pp 222, 263.

- ^ Newcastle Courant, 16 January 1773. The article cites the fuller name of the society, somewhat inaccurately.

- ^ a b Bewick, Thomas, Thomas Bewick: A Memoir written by himself, ed. Iain Bain, OUP 1975, p114.

- ^ W. Hutchinson, A View of Northumberland, Vol.2 (1776), p331

- ^ a b c d Finberg, Hilda F., Two Portraits by William Bell of Newcastle, in The Connoisseur, Vol. LIX (Jan-Apr 1921), p205.

- ^ Graves, Algernon (1969). The Society of Artists of Great Britain, 1760-1791, the Free Society of Artists, 1761-1783: a complete dictionary of contributors and their work from the foundation of the societies to 1791. University of Michigan. Bath (Somerset), Kingsmead Reprints.

- ^ Holmes, June, The Many Faces of Thomas Bewick, in Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Vol. 65, pt 3 (2007), p155.

- ^ Mackenzie, Eneas, A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Town and County of Newcastle upon Tyne, Vol. 1, 1827, p 443-444

- ^ Richard Welford (1895). Men of Mark 'twixt Tyne and Tweed. Harvard University. Walter Scott. pp. 457–461.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie, Eneas, A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Town and County of Newcastle upon Tyne, Vol. 1, 1827, p595. The artist is simply named as "Bell"; this is almost certainly William Bell, whose biography Mackenzie has presented a few pages earlier (p576).

- ^ "Portrait of a Boy Flanked by a Hound and Pony". Mutual Art.

- ^ Horsley, P.M., Eighteenth Century Newcastle, Oriel Press, 1971, p80.

- ^ Green, Richard. "Paul Sandby's Young Pupil Identified". Burlington Magazine.

- ^ Postle, Martin (2020). "Doddington and the Delavals: Collecting and display in the 1760s". Doddington and the Delavals: collection and display in the 1760s. doi:10.17658/ACH/DNE508. S2CID 229487253.

- ^ The accounts of Seaton Delaval Hall record regular payments to "Mr. Bell, Limner."

- ^ Horsley, P.M., Eighteenth Century Newcastle, Oriel Press, 1971, p160.

- ^ In the entries relating to his daughters in the baptism register for the parish of Earsdon, he is plain “William Bell” in 1773, but “Mr. William Bell” in 1777. In 1773 his abode was "Seaton" but in 1777 it was "Ye Fountain Head."

- ^ Horsley, P.M., Eighteenth Century Newcastle, Oriel Press, 1971, p157ff.

- ^ William Bell, Bookbinder, was buried at All Saints Church, Newcastle on 23 Aug 1780.

- ^ According to the burial register of St Andrew's Church, Newcastle (10 Jun 1794), Bell was yeoman (i.e. a property owner) at the time of his death.

- ^ Bewick, Thomas, Thomas Bewick: A Memoir written by himself, ed. Iain Bain, OUP 1975, p113.

- ^ Newcastle Chronicle, Announcements, 11 Jun 1768, 5 Sep 1778, 17 Mar 1781.

- ^ Whitehead, William, The Newcastle and Gateshead Directory for 1782, 83 and 84.

- ^ Newcastle Courant, 11 May 1793, contains a notice referring to "Mr. Bell's, Portrait Painter, Newgate Street."

- ^ Mrs. Jadis was Lord Delaval's daughter, Sophia, who married John Jadis.

- ^ Blyth News, 14 Mar 1891, p5, "The Delaval Papers", quoting a letter sent on 11 May 1788.

- ^ Baillie, John, An Impartial Account of the Town and County of Newcastle upon Tyne, 1801, pp 201 & 276.

- ^ Brand, John, History of Newcastle, Vol. 1, 1789, p544.

- ^ Edwards, Edward, Anecdotes of Painters Who Have Resided or Been Born in England, With Critical Remarks on Their Productions, 1808, p 221