White Hunter Black Heart is a 1990 American adventure drama film produced, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood. It is based on the 1953 book of the same name written by Peter Viertel, who cowrote the screenplay with James Bridges and Burt Kennedy. The screenplay was the last that Bridges wrote before his death in 1993.

| White Hunter Black Heart | |

|---|---|

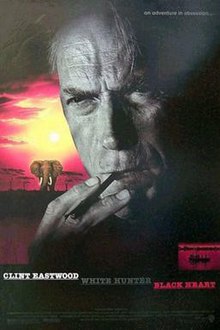

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Screenplay by | Peter Viertel James Bridges Burt Kennedy |

| Based on | White Hunter, Black Heart by Peter Viertel |

| Produced by | Clint Eastwood |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Jack N. Green |

| Edited by | Joel Cox |

| Music by | Lennie Niehaus |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $24 million[1] |

| Box office | $2 million[1] |

The film is a thinly disguised account of Viertel's experiences while working on the 1951 film The African Queen, which was filmed on location in Africa at a time when foreign location shoots for American films were rare. The main character, brash director John Wilson (played by Eastwood) is based on real-life director John Huston. Jeff Fahey plays Pete Verrill, a character based on Viertel. George Dzundza's character is based on African Queen producer Sam Spiegel. Marisa Berenson's character Kay Gibson and Richard Vanstone's character Phil Duncan are based on Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart, respectively.

Plot

editIn the early 1950s, Pete Verrill is invited by his friend, director John Wilson, to rewrite the script for Wilson's latest project: a film with the working title of The African Trader. The hard living, irreverent Wilson convinces producer Paul Landers to have the film completely shot on location in Africa, even though doing so would be extremely expensive. Wilson explains to Verrill that his motivation for this has nothing to do with the film - Wilson, a lifelong hunter, wants to fulfill his dream of going on an African safari; he even purchases a set of finely crafted hunting rifles and charges them to the studio.

Upon landing in Entebbe, Wilson and Verrill spend several days at a luxury hotel while Verrill finishes the script and Wilson makes arrangements for the safari. Verrill finds himself growing fond of Wilson after the latter defends him against a fellow guest who makes antisemitic remarks in front of Verrill (who happens to be Jewish) and challenges the hotel manager to a fistfight after witnessing him insult and belittle a black waiter for spilling a drink. The two men constantly argue over Verrill's changes to the script, particularly his insistence that Wilson does not use his original planned ending, where all of the main characters are killed on-screen.

Wilson hires a pilot to fly him and Verrill out to the hunting camp of safari guide Zibelinsky and his African tracker Kivu, whom Wilson is quick to bond with. The film's unit director, Ralph Lockhart, is also present and insists that Wilson start pre-production before the cast arrives, to which Wilson replies he'll do so after he shoots a "tusker". Verrill gradually becomes disenchanted with Wilson, who keeps going out to hunt despite his poor health and seems completely indifferent to the success of his movie. He even questions why Wilson would want to kill such a magnificent beast.

Confronted, Wilson tells Verrill off and accuses him of "playing it safe" and not wanting to risk anything. He calls hunting a "sin that you can get a license for" and doesn't try to convince Verrill otherwise when he threatens to resign and go back to London. Landers arrives in Entebbe and insists that Verrill stay on, revealing that the studio is at risk of bankruptcy if the movie isn't finished. When Verrill does return, he is informed by Lockhart that Wilson, without consulting anyone, has decided to move the entire production to Kivu's home village despite Landers spending most of the budget on a prefabricated set.

The cast, now unable to stay at the hotel, go to Zibelinsky's camp and find Wilson waiting for them with a lavish banquet. He humiliates Landers and takes advantage of several days of rain to resume his safari, now accompanied by professional elephant hunter Ogilvy. Verrill follows after Wilson again taunts him for cowardice. Wilson finally gets his chance to kill the "tusker", but when the time comes to shoot, he suddenly finds he can't pull the trigger. The elephant suddenly charges after seeing its child move too close to Wilson, and Kivu tries to scare it off only to be fatally gored by the elephant's tusks.

Wilson, horrified by Kivu's death, returns to the set. He sees the villagers beating drums and asks Ogilvy what they mean. Ogilvy replies that they are communicating to everyone how Kivu died: "white hunter, black heart". Recognizing that he is ultimately to blame for what happened, Wilson tells Verrill that he was right: the film does need a happy ending after all. Sitting in his director's chair as the actors and crew take their places to film the opening scene of The African Trader, a now humbled Wilson silently mutters "Action".

Cast

edit- Clint Eastwood as John Wilson

- Jeff Fahey as Pete Verrill

- Alun Armstrong as Ralph Lockhart, unit director

- George Dzundza as Paul Landers

- Charlotte Cornwell as Miss Wilding, Wilson's secretary

- Norman Lumsden as George, Wilson's butler

- Marisa Berenson as Kay Gibson

- Richard Vanstone as Phil Duncan

- Catherine Neilson as Irene Saunders, an aspiring writer who pitches her film to Wilson

- Edward Tudor-Pole as Reissar, British partner

- Roddy Maude-Roxby as Thompson, British partner

- Richard Warwick as Basil Fields, British partner

- Boy Mathias Chuma as Kivu

- Timothy Spall as Hodkins, bush pilot

- Clive Mantle as Harry, Hotel Manager

Production

editDuring the 1950s, Ray Bradbury wrote an unproduced version of the film for MGM.[2] In 1974, Columbia Pictures advertised the film as being readied for production to be directed by Bridges and produced by Ted Richmond.[3]

At times, Eastwood, as the John Huston-like character of John Wilson, can be heard drawing out his vowels, speaking in Huston's distinctive style.

The film was shot on location in Kariba, Zimbabwe, and surrounds including at Lake Kariba, Victoria Falls, and Hwange,[4] over two months in the summer of 1989.[5] Some interiors were shot in and around Pinewood Studios in England. The boat used in the film was constructed in England of glass fiber and shipped to Africa for filming.[4] It was electrically powered, and was fitted with motors and engines by special-effects expert John Evans to make the boat appear to be steam-powered.[4] The elephant gun used in the film was a £65,000 double-barreled rifle of the type preferred by most professional hunters and their clients in this era. It was made by Holland & Holland, the gunmakers who also made the gun used by Huston when he was in Africa for The African Queen in 1951. The White Hunter Black Heart filmmakers took great care with the gun and sold it back to Holland & Holland after filming "unharmed, unscratched, unused."[4]

Reception

editIn a contemporary review for The New York Times, critic Janet Maslin wrote:

In fact, this material marks a gutsy, fascinating departure for Mr. Eastwood, and makes it clear that his directorial ambitions have by now outstripped his goals as an actor. 'White Hunter, Black Heart,' even when not entirely successful, goes far beyond the particulars of Huston's adventures and explores Mr. Eastwood's own thoughts about artistry in general, film making in particular and hubris in all its many forms. ... And none of it works as fully as Mr. Eastwood obviously wants it to, as a consequence of the sheer sweep and colorfulness of the man being portrayed. But even in this relatively stiff, sometimes awkward form, the John Wilson character is as compelling as Mr. Eastwood's desire to play him.[6]

White Hunter Black Heart was entered in the 1990 Cannes Film Festival.[7]

The film has an 83% positive rating on review-aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes, and the consensus reads: "White Hunter Black Heart is powerful, intelligent, and subtly moving, a fascinating meditation on masculinity and the insecurities of artists."[8]

Jim Hoberman of The Village Voice hailed White Hunter Black Heart as "Eastwood’s best work before Unforgiven...[an] underrated hall-of-mirrors movie about movie-inspired megalomania."[9] The film has also been retrospectively praised by critics such as Dave Kehr and Jonathan Rosenbaum.[10]

Box office

editWhite Hunter Black Heart's gross theatrical earnings reached just over $2 million, well below the film's $24 million budget.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c Hughes, Howard, Aim for the Heart: The Films of Clint Eastwood, p.147, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- ^ "Ray Bradbury's lost TV show with ORSON WELLES and his unused ending for KING OF KINGS". December 3, 2007.

- ^ "And More To Come...With These Projects Now Being Readied For Production! (advertisement)". Variety. May 8, 1974. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Production designer John Graysmark interview, Cue International May 1990.

- ^ Hughes, Howard, Aim for the Heart: The Films of Clint Eastwood, p.144, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 14, 1990). "Eastwood Follows The Trail Of the Elusive, Essential Huston". The New York Times. p. C1.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: White Hunter Black Heart". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ "White Hunter Black Heart (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Hoberman, Jim (July 13, 2010). "Voice Choices: White Hunter, Black Heart". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (December 1, 2009). "A Free Man". Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2015.