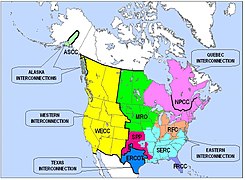

The Western Interconnection is a wide area synchronous grid and one of the two major alternating current (AC) power grids in the North American power transmission grid. The other major wide area synchronous grid is the Eastern Interconnection. The minor interconnections are the Québec Interconnection, the Texas Interconnection, and the Alaska Interconnections.

All of the electric utilities in the Western Interconnection are electrically tied together during normal system conditions and operate at a synchronized frequency of 60 Hz. The Western Interconnection stretches from Western Canada south to Baja California in Mexico, reaching eastward over the Rockies to the Great Plains.

Interconnections can be tied to each other via high-voltage direct current power transmission lines (DC ties) such as the north-south Pacific DC Intertie, or with variable-frequency transformers (VFTs), which permit a controlled flow of energy while also functionally isolating the independent AC frequencies of each side. There are six DC ties to the Eastern Interconnection in the US and one in Canada,[1] and there are proposals to add four additional ties.[2] It is not tied to the Alaska Interconnection.

Consumption

editIn 2015, WECC had an energy consumption of 883 TWh, roughly equally distributed between industrial, commercial and residential consumption. There was a summer peak demand of 150,700 MW and a winter peak demand (2014–15) of 126,200 MW.[3]

Production

editThe region had a nameplate capacity of 265 GW in 2015, 276 GW in 2019, and 286 GW in 2021.[4] Together, wind, solar, and hydro resources account for 47% of installed capacity. Installed coal capacity was 24 GW, compared to roughly 34 GW of wind and 28 GW of solar. While the resource mix is changing, with wind and solar eclipsing coal in installed capacity, in 2021 coal still generated slightly more power than wind and solar combined, down from twice as much in 2017.[3][4]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Transmission". Archived from the original on 2014-12-24. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- ^ Visualizing The U.S. Electric Grid

- ^ a b 2016 State of the Interconnection page 10-14 + 18-23. WECC, 2016. Archive

- ^ a b "State of the Interconnection 2023" (PDF). wecc.org. March 24, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 23, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.