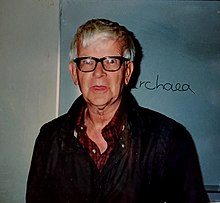

Wesley Conrad Wehr (April 17, 1929 – April 12, 2004) was an American paleontologist and artist best known for his studies of Cenozoic fossil floras in western North America, the Stonerose Interpretive Center, and as a part of the Northwest School of art. Wehr published two books with University of Washington Press that chronicled his friendships with artists and scientists.[1][2]

Wesley Conrad Wehr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 17, 1929 |

| Died | April 12, 2004 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Fossil leaf analysis, painting |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleobotany, The Northwest School |

| Institutions | Burke Museum |

Early life

editWesley Wehr was born as the only child of Conrad J. Wehr and Ingeborg (Hall) Wehr, in Everett, Washington on April 17, 1929. As a child he displayed an aptitude for music which was encouraged with private lessons. In his senior year of high school two of his compositions, Pastoral Sketches for Violin and Piano and Spanish Dance, came to the attention of George F. McKay, then an instructor at the University of Washington. McKay invited Wehr for private study with him, and in 1947 Wehr entered the University.[2]

Northwest School

editWehr graduated the University of Washington in 1952 with a Bachelor of Arts and a recipient of the Lorraine Decker Campbell Award for original composition, then continued on to his Master of Arts in 1954. After graduation he took a position as watchman in the Henry Art Gallery on the weekends, passing the time between visitors by doodling.[2] Wehrs only published music score Wind and the Rain was released in 1957 though Dow Music in New York. However after a comment by Theodore Roethke, Wehr became self-conscious of his musical works and stopped composing feeling that "The life went out of it".[2]

Wehr started out studying music composition, and later expanded to poetry classes with Roethke in his senior year of university. Northwest School Painter Mark Tobey was introduced to Wehr in 1949 by mutual friend and pianist Berthe Poncy Jacobson. An undergraduate at the time, he accepted the opportunity to serve as a stand-in music composition tutor for Tobey, and over time became friends with him and his circle of artists. Tobey introduced him to Guy Anderson and Morris Graves at a Christmas party in 1949 and later Kenneth Callahan, Pehr Hallsten, and Helmi Juvonen. Tobey encouraged him in painting, and Guy Anderson insisted he learn how to draw.[2] Wehr first began painting in 1960,[3] being inspired by pots of paint and a box of Crayola crayons over the Christmas holidays. With his group of friends gone home for the holiday, he drew on memories of the Oregon coast and the picture agate found in thundereggs, producing several landscapes that were no more than 6 in (15 cm) on a side.[2] His first additions to the Northwest School.[4]

Wehr was a student of the noted poet Elizabeth Bishop in 1953, and in 1967 she wrote a gallery note for a showing of Wehr's paintings. In the gallery note she commented on the small size of his works and compared them to short works of music. In a similar reflection, Bishop commented on Wehr transporting new works in an old briefcase and showing them at a local coffee house, and the effect the painting had on those viewing them. Bishop notes that Wehr was a collector of natural objects such as agates, amber, and fossils. She noted that Wehr's works possessed a "chilling sensation of time and space".[5]

Throughout his life Wehr collected signatures, and often wrote to people as an opening to get one. Some of the letters grew into more in-depth correspondence, including conversations with Vincent Price, Suzanne Langer and Katharine Hepburn.[4] A selection of Wehrs and Joseph Goldbergs works were featured as part of the Spokane, Washington Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture 2021 exhibit "Inspired by Landscape", both of whose works were inspired by the landscapes of Eastern Washington.[6]

Paleontology

editWehr met the future chief curator of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, Kirk Johnson, when Johnson was in his early teens. As Wehr had never learned to drive, when Johnson got his driver's license, Wehr and Johnson took a week-long trip through Eastern Washington. It was on this trip that Wehr and Johnson first visited Republic, Washington to find fossils.[7]

In the 1970s, he started to focus on paleobotany, guided by his correspondence with noted paleobotanists Charles N. Miller, Jr and Chester A. Arnold. He continued his love of petrified wood through correspondence with George Beck of Central Washington University. The 1977 visit to Republic led to the realization of the richness of the Republic Flora. Until his work in the 1970s the fossils of Republic were regarded as little more than a minor flora.[3] In the early 1980s working with Republic councilman Bert Chadwick, Wehr helped with the initial setup and organization of the Stonerose Interpretive Center.[2][3]

In 1976, Wehr was appointed as an affiliate curator of paleobotany at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Wehr maintained this position for the rest of his life. Through his contacts and work both in Republic and the Burke Museum he authored a series of papers on the fossils found at Republic. A group of ten papers published in the now defunct publication Washington Geology were aimed at a general audience. He also coauthored several technical scientific papers with paleobotanical colleagues. Wehr was recognized for his work with fossils in 2003 when he was awarded the Paleontological Society's Harrell L. Strimple Award, awarded each year to an amateur who has contributed to paleontology, with Kirk Johnson noting that "throughout his career, Wes has been an exporter of paleontology".[4] The reception hosted by Wehr at the Burke Museum afterwards was attended by 200 of his friends and acquaintances, at which Wehr noted one of his inspirations to be Richard Fuller, geologist, vulcanologist, but also founder of the Seattle Art Museum. Similar to Wehr were also Beck, who was an accomplished musician, and V. Standish Mallory who trained in his early life as a composer and musician.[8]

A number of extinct plants and insects were named in honor of Wehr including Cretomerobius wehri, Osmunda wehrii, Pseudolarix wehrii, and Wessiea yakimaensis. The fossil flower, Wehrwolfea striata was named for Wehr and paleobotanist Jack Wolfe.[3] While traveling with Kirk Johnson in 1992, Wehr visited the Black Hills Institute and saw the skeleton of the Tyrannosaurus rex Sue five days before it was seized by the FBI.[7]

Five days before his 75th birthday, Wehr suffered a series of heart attacks[9] and died on April 12, 2004. The planned birthday party was changed into a memorial service, attended by more than 200 people.[3]

References

edit- ^ Wehr W 2000 "The eighth lively art : conversations with painters, poets, musicians & the wicked witch of the west" University of Washington Press, Seattle; and Wehr W 2004 "The Accidental Collector" University of Washington Press, Seattle

- ^ a b c d e f g Arment, Deloris Tarzan (July 17, 2002). "Wehr, Wesley (1929–2004): Preserver of Fossils". Seattle: HistoryLink. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Archibald, S. B.; et al. (2005). "Wes Wehr dedication". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 42 (2): 115–117. Bibcode:2005CaJES..42..115A. doi:10.1139/E05-013.

- ^ a b c Johnson, K. (2004). "Presentation of the Harrell L. Strimple award of the Paleontological Society to Wesley C. Wehr". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (4): 822. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0822:POTHLS>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130210589.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Susan B. (2007). Professing sincerity: modern lyric poetry, commercial culture, and the crisis in reading. University of Virginia Press. pp. 188–190. ISBN 978-0-8139-2610-0.

- ^ Kimberly Lusk (June 27, 1902). "Family Fun: Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture features exhibits for engagement, exploration". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Johnson, Kirk; Ray Troll (2007). Cruisin' the Fossil Freeway: An Epoch Tale of a Scientist and an Artist on the Ultimate 5000-Mile Paleo Road Trip. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing. pp. 3, 66. ISBN 978-1-55591-451-6.

- ^ Wehr, W. (2004). "Response by Wesley Wehr". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (4): 823–824. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0823:RBWW>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198152585.

- ^ Burke Museum press release accessed August 11, 2011