The Wehrmacht exhibition (German: Wehrmachtsausstellung) was a series of two exhibitions focusing on the war crimes of the Wehrmacht (the regular German armed forces) during World War II. The exhibitions were instrumental in furthering the understanding of the myth of the clean Wehrmacht in Germany. Both exhibitions were produced by the Hamburg Institute for Social Research; the first under the title "War of Annihilation. Crimes of the Wehrmacht 1941 to 1944",[1] which opened in Hamburg on 5 March 1995 and travelled to 33 German and Austrian cities. It was the subject of a terrorist attack but the organizers nonetheless claimed it had been attended by 800,000 visitors.[2] The second exhibition – which was first shown in Berlin in November 2001 – attempted to dissipate considerable controversy generated by the first exhibition according to the Institute.[3]

History

editThe popular and controversial travelling exhibition was seen by an estimated 1.2 million visitors over the last decade. Using written documents from the era and archival photographs, the organizers had shown that the Wehrmacht was "involved in planning and implementing a war of annihilation against Jews, prisoners of war, and the civilian population". Historian Hannes Heer and Gerd Hankel had prepared it.[4]

The view of the "unblemished" Wehrmacht was shaken by the material evidence put on public display in different cities including Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, Bielefeld, Vienna, and Leipzig.[3] On 9 March 1999 at 4:40am, a bomb attack on the exhibition occurred in Saarbrücken, damaging the adult high school building housing the exhibition and the adjoining Schlosskirche church.[5]

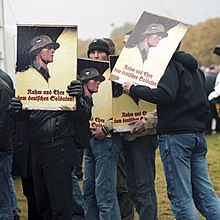

On 25 April 1995, 75-year-old Wehrmacht veteran Reinhold Elstner committed self-immolation in front of the Feldherrnhalle to protest against the Wehrmacht exhibition. Each year neo-fascist groups from various European countries hold a commemorative ceremony for him.[6] In an open letter, Elstner pleaded with ethnic Germans around the world to "awaken" and denounced the gas chambers of Auschwitz as "fairy tales."[7]

Wrongly attributed images, criticism and review

editAfter criticism about allegedly incorrect attribution such as pictures of Soviet atrocities wrongly attributed to Germans and captioning of some of the images in the exhibition, the exhibition was heavily criticized by some historians such as Polish-born historian Bogdan Musiał[8] and Hungarian historian Krisztián Ungváry. Ungváry claimed that only ten percent of the 800 photos of war crimes were in fact German Wehrmacht crimes and the rest were Soviet war crimes or crimes committed by Hungarian, Finnish, Croatian, Ukrainian or Baltic forces, or by members of the SS or SD, none of whom were members of the Wehrmacht, or not crimes at all.[9]

The head and founder of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research,[10] Jan Philipp Reemtsma suspended the display, pending review of its content by a committee of historians. The review stated that contrary to Ungváry, only 20 out of 1400 pictures were found to be of Soviet atrocities.[11]

The committee’s report acknowledged that the exhibit’s documentation contained inaccuracies and that its arguments may have been too sweeping. It concluded, however, that the Wehrmacht had indeed led a war of annihilation and committed atrocities. The accusation of forged materials was found to be unjustified. In a written statement, Reemtsma said:[12]

We greatly regret that we did not respond to a number of critics, whose objections have been shown to be correct, with due earnestness and that we did not decide to impose a moratorium at an earlier date. Nonetheless, we reiterate that the key statement of the exhibition – that the Wehrmacht led a war of aggression and annihilation – is correct and is upheld.

In its report from November 2000, the committee reaffirmed the reliability of the exhibition in general, explaining that the errors had already been corrected. The committee recommended that the exhibition be expanded to include perspectives of the victims as well, presenting the material but leaving the conclusions to the viewers.[2]

The fundamental statements made in the exhibition about the Wehrmacht and the war of annihilation in 'the east' are correct. It is indisputable that, in the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht not only 'entangled' itself in genocide perpetrated against the Jewish population, in crimes perpetrated against Soviet POWs, and in the fight against the civilian population, but in fact participated in these crimes, playing at times a supporting, at times a leading role. These were not isolated cases of 'abuse' or 'excesses'; they were activities based on decisions reached by top level military leaders or troop leaders on or behind the front lines.[2]

Notably, the exhibition does not inform about the Wehrmacht's crimes in occupied Poland on either side of the Curzon Line. They were presented later as an entirely different exposition called Größte Härte: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht in Polen September/Oktober 1939 (Crimes of the Wehrmacht in Poland, September/October 1939) by the Deutsches Historisches Institut Warschau.[13]

Revised exhibition, 2001–2004

editThe revised exhibition was renamed Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941–1944. ("Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation 1941-1944").[14] It focused on public international law and travelled from 2001 to 2004. Since then, it has been moved permanently to the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin.

Films

editThe documentary Der unbekannte Soldat (The unknown soldier) by Michael Verhoeven was in cinemas from August 2006, and has been available on DVD since February 2007. It compares the two versions of the exhibitions, and the background of its maker Jan Philipp Reemtsma.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (6 December 2002). "The exhibition "Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941-1944" in Luxemburg". Hamburg. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ a b c "Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation 1941-1944" (PDF). An outline of the exhibition. Hamburg Institute for Social Research. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

- ^ a b Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (8 October 2002). "Exhibition "Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation, 1941-1944" opens in Munich". Hamburg. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Hannes Heer (former staff member) (December 2000). "The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust". Hamburg: Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Karl-Otto Sattler (1999-03-10). "Sprengstoffanschlag auf Wehrmachtsausstellung". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 2012-07-20.

- ^ Milligan, Tony (2022-07-08). The Ethics of Political Dissent. Taylor & Francis. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-429-66356-7.

- ^ "Book: The Self Immolators (2013) – The Speaker News Journal". 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ "DA 10/2011 - Musial: Der Bildersturm". September 2011.

- ^ Müller, Rolf-Dieter (1995), Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944 (in German), Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung Militärgeschichtliche Mitteilungen, p. 324

- ^ "Wehrmachtsausstellung: Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung trennt sich von Hannes Heer". Der Tagesspiegel Online. 14 August 2000.

- ^ Semmens, Kristin (2006), Review of Heer, Hannes, Vom Verschwinden der Täter: Der Vernichtungskrieg fand statt, aber keiner war dabei, H-German, H-Review, retrieved 2019-08-16

- ^ "Crimes of the German Wehrmacht: Dimensions of a War of Annihilation 1941-1944: Press releases, January to November 2000" (PDF). Hamburg Institute for Social Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 24, 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ^ Größte Härte ... Verbrechen der Wehrmacht in Polen September/Oktober 1939

- ^ "Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941—1944". Retrieved 2006-03-12.

- Heer, Hannes; Klaus Naumann, eds. (1995). Vernichtungskrieg: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944 (War of Annihilation: Crimes of the Wehrmacht). Hamburg: Hamburger Edition HIS Verlag. ISBN 3-930908-04-2.

Further reading

edit- Hartmann, Christian; Hürter, Johannes; Jureit, Ulrike (2005): Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Bilanz einer Debatte [Crimes of the Wehrmacht: Review of the Debate], Munich: C.H. Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-52802-6

External links

edit- Institut für Sozialforschung: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941-1944

- Bericht der Kommission zur Überprüfung der Ausstellung "Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944" (PDF, 362 KB)

- Deutsche Nationalbibliothek: Titel zum Thema

- Volker Ullrich (Die ZEIT, 22 January 2004): Conversation with Ulrike Jureit, Jan Philipp Reemtsma and Norbert Frei to close the exhibition

- 'Zwei Ausstellungen - eine Bilanz' von Jan Philipp Reemtsma

- Klick-nach-rechts: Materialiensammlung rund um die Wehrmachtsausstellung

- "The Wehrmacht exhibition that shocked Germany" at Witness History (BBC World Service)