Vicente's poison frog (Oophaga vicentei) is a species of frog in the family Dendrobatidae that is endemic to the Veraguas and Coclé Provinces of central Panama.[2][3]

| Vicente's poison frog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Dendrobatidae |

| Genus: | Oophaga |

| Species: | O. vicentei

|

| Binomial name | |

| Oophaga vicentei (Jungfer, Weygoldt & Juraske, 1996)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dendrobates vicentei | |

Appearance

editThe adult male and female frogs are 12 to 24 mm long in snout-vent length. This frog is known for its striking coloration, which has made it a target for collection for the international pet trade. The skin of the frog's back can come in any of several background colors, such as yellow, red, blue, gray, or green. Most individuals have black or dark brown reticulated patterns on their backs and the upper sides of all four legs. Young froglets have much more black colorartion. The frog's snout can be round or pointed.[3][1]

Habitat

editThis frog inhabits humid tropical lowland and montane rainforests, where it has been observed between 4 and 912 meters above sea level. It is principally arboreal, but people have seen it foraging for food on the ground. This frog is active during the day.[3][1]

Reproduction

editVicente's poison frog breeds in arboreal vegetation. The male frog finds a good place for the female frog to lay eggs, usually near the leaf of a bromeliad plant high in a tree. He calls to the female and she approaches. Both frogs engage in wiping motions with their hind legs. The female frog turns in circles before and after laying her eggs. She lays 1 - 12 eggs per clutch. Both the male and female frog then leave rather than remain to guard the eggs, but the male frog returns to moisten them about once per day.[3]

After the eggs hatch, the female frog carries each tadpole on her back to a vegetation-bound water pools in bromeliads to develop. As the generic name Oophaga indicates, this and related species also practice a particular form of oophagy, where the mother deposits special nutritive eggs for the larvae to consume.[4] When the female approaches the pool to lay this trophic egg, the tadpole will swim and vibrate near the surface. When she submerges herself to lay the egg, the tadpole may bump into her. Tadpoles have been observed exhibiting this behavior even for O. vicente females that are not their mothers. The tadpoles are obligate egg-eaters and do not consume any other food. The female frog does not lay a new clutch of eggs during this time.[3]

Female O. vicente frogs kept in terrariums have been observed eating other O. vicente females' eggs. Scientists do not know if female O. vicente frogs in the wild also cannibalize each other's eggs or if this is something frogs in captivity do.[3]

Diet and poison

editA male frog's stomach contents consist mostly of insects and other arthropods, including ants and mites that produce alkaloids. Specifically, scientists found ants from the genera Solenopsis and Tapinoma, which produce pumiliotoxin alkaloids and actinidin. Scientists believe that the pumiliotoxin is involved in the frog's own poison and that the actinidin might be, but this has not been confirmed as of 2023.[3]

Threats

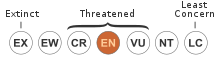

editThe IUCN classifies this frog as endangered because of its small range, which is subject to ongoing degradation. Humans cut down forests for mining, agriculture, cattle grazing, and urbanization. This frog is also caught in the wild and sold as part of the international pet trade because it is so beautiful.[1]

Scientists believe the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis could infect and kill this frog because it has killed other frogs in the area. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis causes the fungal sickness chytridiomycosis.[1]

The frog's known range includes two protected parks: Santa Fé National Park and General de División Omar Torrijos Herrera National Park. The Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project also collected some frogs to raise in captivity.[1]

Original publication

edit- Jungfer K.-H.; Weygoldt, P.; Juraske, N. (1996). "Dendrobates vicentei, ein neuer Pfeilgiftfrosch aus Zentral-Panama". Herpetofauna. 18 (103): 17–26.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2019). "Oophaga vicentei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T55209A54344862. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T55209A54344862.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Frost, Darrel R. (2014). "Oophaga vicentei (Jungfer, Weygoldt, and Juraske, 1996)". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jonathan Sedano (September 29, 2023). Ann T. Chang; Michelle S. Koo (eds.). "Oophaga vicentei (Jungfer, Weygoldt, and Juraske, 1996)". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ Grant, Taran; Frost, Darrel R.; Caldwell, Janalee P.; Gagliardo, R. O. N.; Haddad, Celio FB; Kok, Philippe JR; Means, D. Bruce; Noonan, Brice P.; Schargel, Walter E.; Wheeler, Ward C. (2006). "Phylogenetic systematics of dart-poison frogs and their relatives (Amphibia: Athesphatanura: Dendrobatidae)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 2006: 177–179.