The veto power in Illinois exists in the state government as well as many municipal and some county governments. The gubernatorial veto power is established in the Illinois Constitution, and is one of the most comprehensive vetoes in the United States. It began as a suspensive veto exercised jointly with the Supreme Court but has grown stronger in each of the state's four constitutions. The gubernatorial veto power consists of two vetoes that apply to all bills passed by the General Assembly (the full veto and the amendatory veto) and two vetoes that apply only to appropriations measures (the line-item veto and the reduction veto).

Other veto powers have been created by statute. The General Assembly has reserved a veto power over administrative regulations through the Joint Committee on Administrative Regulations, the constitutionality of which has sometimes been disputed.

Veto powers also exist in county and municipal governments. The veto power of the president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners was established by state law in 1887, and in 1970 an executive veto system was made available to counties statewide, although only two counties have adopted it. The mayoral veto in municipalities likewise dates to the 19th century and has been gradually strengthened over time.

Gubernatorial veto

editThe governor of Illinois has four veto powers: a full veto, an amendatory veto, and for appropriations bills a line-item veto and a reduction veto. Together, these powers make the Illinois gubernatorial veto one of the strongest in the country.[2] The Illinois General Assembly can override all of these vetoes by a three-fifths majority of both chambers.

In the case of a full veto, the governor rejects the bill as a whole. The legislature can override the veto, causing the bill to become law, by a three-fifths vote of the voting members of each legislative chamber.[3]

In the case of an amendatory veto, the governor returns the vetoed bill with specific suggestions for change. The legislature can either accept the governor's suggestions by a simple majority vote of both chambers, or reject them by overriding the veto. If the legislature takes no action, the bill dies. If the legislature approves an amended law in response to the governor's changes, the bill becomes law once the governor certifies that the suggested changes have been made.[4] The governor can use an amendatory veto to make substantive changes to a bill, but cannot replace the whole text of the bill.[5] The amendatory veto gives the governor "remarkable power" in the legislative process, but typically becomes a source of controversy only when the governor uses it as a public relations tool.[6]

A line-item veto rejects one or more items in an appropriations bill. The legislature can override a line-item veto by a three-fifths vote of both chambers, as in the case of a full veto.[4]

Like a line-item veto, a reduction veto applies to one or more items in an appropriations bill, but instead of eliminating them entirely, the governor reduces their amount. The reduced appropriation takes effect and becomes available as soon as the governor issues the reduction veto.[7] The legislature can override a reduction veto by an absolute majority vote of both chambers.[4]

A veto can affect the date of passage of legislation, which in turn affects the law's effective date. If the General Assembly overrides a veto, the law's date of passage is considered to be the same as if it had not been vetoed (namely the date of final passage before the bill was sent to the governor the first time).[8] In the case of an amendatory veto, if the governor's changes are accepted, the law's date of passage is the date on which the General Assembly accepted the changes.[8]

The amendatory and reduction vetoes, which were both adopted for the first time in the 1970 constitution,[7] have been described as "fine-tuning" vetoes, in contrast to the blunt all-or-nothing nature of the full and line-item vetoes.

One type of veto the governor does not have is a pocket veto: if the governor does not sign or veto a bill within 60 days of passage, it becomes law automatically.[7]

History

editUnder territorial government, which was governed by the Northwest Ordinance, the appointed governor had an absolute veto over legislation passed by the territorial legislature. The legislature sent several petitions to Congress seeking repeal of the governor's veto power.[9] The ability of an appointed official to completely prevent action by the elected legislature helped spur the movement for Illinois statehood, which was accomplished in 1818.[10]

A particularly notable use of this veto power occurred on New Year's Day 1818, when governor Ninian Edwards vetoed legislation that would have repealed the Illinois Territory's indenture laws. Although the veto was absolute in any case, the governor subsequently prorogued the territorial legislature to prevent any further discussion of the topic. The effect of the veto was to make the issues of slavery and the veto power foremost during the 1818 delegate elections and the ensuing First Illinois Constitutional Convention.[11]

Early statehood

editUnder the 1818 Illinois Constitution, Illinois adopted New York's "council of revision" system.[12] The Illinois Council of Revision consisted of the governor and the justices of the Illinois Supreme Court. The Council of Revision had 10 days to veto legislation before it would become law.[13] It could veto legislation by majority vote, but this was only a suspensive veto, because the legislature could override it by a majority vote of both houses. A veto had to include reasons and suggested revisions to the vetoed bill. While the Council of Revision language in the constitution was largely copied verbatim from New York's, Illinois differed in adopting a suspensive veto rather than the two-thirds supermajority required to override the New York council's vetoes.[14]

Under the 1818 system, the Council of Revision vetoed about 3.3% of bills (104 out of 3158 enactments). About 10% (11 out of 104) of these vetoes were overridden. About two-thirds of vetoed legislation was amended along the lines suggested by the Council of Revision.[13]

The 1848 Illinois constitution was dominated by a spirit of Jacksonian Democracy, which favored a strong executive. The Democratic Party platform for the Second Illinois Constitutional Convention included an effective gubernatorial veto, with a two-thirds requirement for override.[15] The Democrats obtained a 91-71 majority over the Whigs in the convention, and under the resulting constitution, the Council of Revision was abolished and the governor exercised the veto power directly.[16] Illinois became the last state in the country to eliminate the council of revision system, which New York had abandoned in 1821.[17] However, as a result of a coalition between the Whigs and some Democrats, the veto override threshold was whittled down, first from two-thirds to three-fifths, and then from three-fifths to a simple majority.[18][19]

In 1862, the Third Illinois Constitutional Convention proposed a constitution that included a two-thirds override threshold.[20] However, the proposed constitution was defeated amid accusations of partisanship and disloyalty by the members of the Democratic-majority convention.[21]

Under the 1848 system, only 28 vetoes were issued from 1848 to 1868, and only two of these were overridden. However, in 1869 governor John M. Palmer vetoed 72 bills, and the legislature overrode 17 of these vetoes. This resulted in a total of 1.3% of legislation passed under the 1848 system being vetoed, and 19% of vetoes being overridden.[22] Among the bills that Palmer vetoed was antimonopoly legislation that would have set maximum rates for railroads; the discussion of that issue then shifted to the 1869 constitutional convention, where it became a major point of controversy.[23]

1870 constitution

editAfter the Civil War, the quantity of private legislation passed by the Illinois legislature rose sharply, which led to calls for a strengthened gubernatorial veto power. The nine-member committee on the executive article in the Fourth Illinois Constitutional Convention unanimously recommended a veto power with an override threshold of two-thirds of the membership of both chambers. Presenting the executive article to the convention at large, committee chair Elliott Anthony opined that the proposed veto provision would have saved the state from "untold miseries".[24] The 1870 Illinois constitution followed a national trend toward strengthening executive power.[25] The trend was strengthened in Illinois by the high esteem in which the members of the convention held Governor Palmer, even asking for his veto messages to be reprinted so they could be mined for items of constitutional significance.[26] The resulting constitution raised the override threshold to two-thirds of the total membership of each house. The ten-day deadline was retained.[22]

Over the century under which Illinois was governed by the 1870 constitution, it was very rare for any override attempt to muster the required two-thirds vote in both chambers.[27] This was a general trend among states, particularly among the 22 states that adopted the same high threshold as Illinois,[28] but it was particularly severe in Illinois because of how representatives were elected.[27] Three representatives under the 1870 constitution were elected at-large within each senate district and only two could be from the same party, so a party could gain a two-thirds majority only by winning every district in the state, and in practice party majorities were much smaller.[27] As a result the governor's veto became nearly absolute in practice.[22] In the mid-20th century, the proportion of legislation vetoed varied between 1/6 and 1/8.[27] Only three vetoes were overridden from 1870 to 1968, and none after 1936.[29]

Over this period, the proportion of legislation vetoed fell at first, from 4.6% in 1868–1872 to 2.6% in 1872–1900. It then rose to 12% for 1900-1916 and continued above 10% through 1936.[30] At the same time, the proportion of vetoes arising from policy disputes (rather than technical or constitutional deficiencies) rose sharply.[31]

The veto provision affected the timing of the legislative session. 1870 constitution provided that legislation generally took effect on the July 1 following passage. As a result there was great pressure to pass legislation, and consider any vetoes, by June 30. Until the 1930s the legislature typically adjourned early enough that it could reconvene to consider any veto messages before June 30. This practice later fell out of favor, but in 1967, by mutual agreement of the houses, a fall veto session was held (during which the legislature attempted to override twelve vetoes without success).[29]

Among the earliest amendments to the 1870 constitution was the adoption of the line-item veto. In 1883, governor Shelby Moore Cullom asked the legislature for a line-item veto, noting that Illinois mayors had been given this power in 1875. A constitutional amendment to this effect was introduced in the state senate by William Beatty Archer, an advocate of strong vetoes who had served in two previous constitutional conventions, and was approved by overwhelming majorities in both chambers. In 1884, the voters approved the constitutional amendment by a 63% majority.[32][33] This allowed the governor to strike entire items from an appropriations bill, but not to amend or reduce them, as the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in 1915.[34] No governor actually used the item veto until 1899, 15 years after its adoption, and it was not used again until 1903.[35]

1970 constitution

editIn adopting the 1970 Illinois Constitution, the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention made a number of changes to the gubernatorial veto power. The governor's deadline for veto was extended to 60 days, and the threshold for override was reduced to three-fifths of members voting in each chamber. In addition, the governor was supplied with amendatory and reduction vetoes.[36]

With the adoption of the 1970 constitution, Illinois became the fifth US state to give its governor an amendatory veto.[37] Unlike the reduction veto, the amendatory veto had not been widely discussed before the convention. Proposing amendments as part of the veto message had been part of Illinois legislative practice since statehood, but this practice was no longer followed by the 1960s.[38] At the convention, the amendatory veto was discussed in the Executive Committee, although it ultimately ended up in the legislative article. Discussing the provision on its first reading before the convention at large, Executive Committee member Frank Orlando stated that it introduced "something new in the constitutional history of Illinois".[39]

The amendatory veto was exercised 200 times between 1971 and 1975; 153 of the amendments were adopted and six were overridden.[40] The scope of the amendatory veto became a point of controversy during this period. Although the convention anticipated that the amendatory veto would be used chiefly to correct minor technical errors, most of these were vetoed on general policy grounds.[41] The amendatory veto was widely seen as a radical departure from earlier practice, and after governors began to use it in the early 1970s, some legislators charged that Illinois democracy was at risk. Representative John S. Matijevich opined that the amendatory veto "places dictatorial powers in the hands of the governor."[42]

In People ex rel. Klinger v. Howlett, the Illinois Supreme Court examined the governor's very first use of the amendatory veto in 1971, in which the governor structured his proposed amendment in traditional legislative terms as "striking everything after the enacting clause". The court disfavored this approach, although the decision did not ultimately turn on the question.[43] A more aggressive use of the amendatory veto was employed by Dan Walker in 1976, in which the governor returned a school funding bill with amendments to delete some sections unless a tax policy favored by the governor was adopted.[44] The move was successful but was widely criticized.[44]

Members of the Executive Committee opined that the governors' use of the amendatory veto power had departed from their original intent, which was that it be used only for minor technical corrections.[45] Before the advent of computerized drafting, technical inconsistencies between bills were common.[46] Concerned over governors' unfettered use of the amendatory veto, in 1973 the General Assembly took up a constitutional amendment to limit the amendatory veto to the correction of technical issues. Both chambers passed the amendment by overwhelming margins. Placed before the voters in 1974, however, the amendment failed.[47] The Illinois Supreme Court subsequently held that the voters' action in defeating the proposed amendment had eliminated any prior ambiguity in the scope of the amendatory veto.[48]

Legislative veto

editThe 1970 Constitution provides a legislative veto over the governor's reorganization or reassignment of functions, "[i]f such a reassignment or reorganization would contravene a statute".[49] The legislature has 60 days to act on such a proposed change. Each chamber has an independent veto power: if either chamber votes by an absolute majority to disapprove the change, it is vetoed.[49] Illinois is one of seven states with such a constitutional provision.[50]

In addition, as in a number of other states, the Illinois General Assembly has given a joint committee of legislators the power to suspend and block regulations, including emergency regulations, proposed by state administrative agencies.[51][52] This power is exercised by the Joint Committee on Administrative Rules (JCAR). JCAR is made up of twelve members, with equal numbers from the House and Senate and equal numbers from each political party.[53] It can block proposed rules by a three-fifths vote.[54] The General Assembly can reverse a block imposed by JCAR by passing a joint resolution.[54] While half of the US states have a review body with either a suspension-type legislative veto or a nullification-type veto, Illinois is one of five states with a "hybrid" legislative veto that combines both powers.[55]

JCAR was first established in 1978, under the original Illinois Administrative Procedure Act, and was given only advisory powers.[56] The General Assembly gave it the power to temporarily block or suspend administrative regulations for 180 days in 1980.[56] The measure passed by overwhelming margins over the veto of Governor James R. Thompson.[57] If JCAR suspended a regulation, the General Assembly could veto the regulation by a joint resolution, or take no action and allow the regulation to take effect once the suspension expired.[57] In September 2004, the General Assembly expanded this temporary suspension power into a permanent veto.[58] This change made Illinois' legislative veto one of the strongest in the country.[59]

Because the Illinois Constitution does not provide for a legislative veto of administrative regulations, the constitutionality of the JCAR veto has been questioned.[60] Thompson threatened litigation if his regulations were unreasonably blocked under the 1980 system.[57] In the 21st century, Governor Rod Blagojevich took the position that JCAR was unconstitutional and therefore he did not have to respect its rulings. One of the charges against him his 2009 impeachment trial was that he had not respected the legitimacy of JCAR blocking his Illinois Covered rulemaking on healthcare in 2008.[60]

In counties

editIllinois has three forms of county government: the township system, the commissioner system, and the county-executive system.[61] In counties with a county executive system (Cook, Will and Champaign),[61] the county executive has a full veto and a line-item veto, both of which can be overridden by a three-fifths vote of the membership of the county council.[62] Du Page and St. Clair counties have granted executive-like powers to their board presidents but have not granted those presidents a veto power.[63]

The president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners was granted a veto power by state law in 1887.[64] The power is infrequently used. In 2020, board president Toni Preckwinkle issued the first veto in her ten-year tenure, blocking an ordinance that would have made the addresses of people with COVID-19 infections available to first responders.[65]

The county executive system, with its attendant veto powers, was first made generally available statewide under the 1970 Illinois constitution.[36] Governor Kerner had suggested a county executive system of government for Illinois counties as early as 1961.[66] The 1964 Supreme court decision Avery v. Midland County further spurred such reforms.[67] However, in 1969 the Illinois senate voted down a proposed county executive system with veto powers.[68]

In the 1970s, 11 counties held referendums to adopt the county executive system provided under the 1970 constitution, but all of them failed.[69] Rock Island County adopted the county executive system in 1992 but reverted to the township system in 1996.[70] The first county outside of Cook to adopt a county executive system was Will County in 1988. The first executive of Will County, Democrat Charles Adelman, wielded the veto in a power struggle with the heavily Republican county council.[71]

Champaign County voters adopted the county executive system by referendum in 2016.[72] In 2021 the Champaign County executive vetoed a redistricting plan backed by the Democratic members of the county board, but was overridden.[73]

In municipal government

editThe nature of a mayor's veto power under Illinois law depends on the form of government that a city or village has adopted. In cities and villages that have adopted the commission form of government (in which the commissioners are elected at large), the mayor has no veto.[74] In the roughly 80[75] cities and villages that have adopted a managerial form of government, if the members of the council are elected at large, the mayor has a vote but no veto. On the other hand, in a managerial government in which the members of the council are elected by districts, the mayor has a veto only over ordinances that involve spending money, incurring debt or selling property.[76] The council can override the veto by a two-thirds vote of all members.[76]

Illinois' mayors, like the governor, do not have a pocket veto. If the mayor does not return the ordinance to the council at the next session, it becomes law.[77]

A city or village having a population of at least 5,000 may also hold a referendum to adopt a "strong mayor" form of government, under which the mayor has a full veto and line-item veto that the council can override by a three-fifths vote of all members.[78]

The mayor of Chicago, in addition to the full and item vetoes shared with other cities, has a type of amendatory veto. In issuing a full veto the mayor can submit a "substitute ordinance".[79][80] Any two members can have the substitute ordinance sent to committee, which can be prevented only by a two-thirds vote.[81] If the mayor's substitute ordinance is not sent to committee it can be taken up by the council directly, and becomes law if it is supported by a majority of the members voting.[81]

The mayor of Chicago obtained a qualified veto in 1850, part of a nationwide trend toward mayoral veto powers in large cities.[82] An early exercise of this veto occurred in 1852, when the city council overrode mayor Walter S. Gurnee's veto of an ordinance granting the Illinois Central Railroad a right of way along the city lakefront.[83] In 1872 mayor Joseph Medill obtained passage of the "Mayor's Bill", which granted him and other mayors line-item veto among many other increased powers.[84][85]

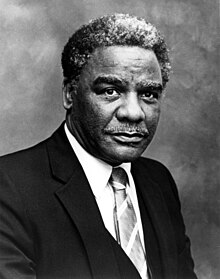

The frequency of use of the mayoral veto in Chicago has varied greatly depending on the relations between the mayor and the city council. Richard M. Daley was in office for 15 years before issuing his first veto to block the 2006 Chicago Big Box Ordinance.[86] In contrast, vetoes played a central role in the Council Wars of the mid-1980s. Mayor Harold Washington's mode of governance during this period has been described as "rule by veto".[1] Washington's former press secretary described the typical process as the city council passing a measure, the mayor vetoing it, and representatives from both sides meeting to work out a compromise.[87] Nearing the end of his first term with the Council Wars largely in the past, Washington reflected that "it was the threat of the veto that permitted us to have a working relationship that is probably as good as any executive-legislative working relationship in any city in this country."[88]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Losier, Toussaint (2017). ""The Public Does Not Believe the Police Can Police Themselves": The Mayoral Administration of Harold Washington and the Problem of Police Impunity". Journal of Urban History: 11. doi:10.1177/0096144217705490.

- ^ Lousin, Ann (2011). The Illinois State Constitution. Oxford Commentaries on the State Constitutions of the United States. Oxford University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780199766925.

- ^ Article IV, Section 9 of the Constitution of Illinois (1970)

- ^ a b c Article IV, Section 9(d) of the Constitution of Illinois (1970)

- ^ Lousin 2011, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Lousin 2011, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Lousin 2011, p. 120.

- ^ a b Lousin 2011, p. 123.

- ^ Cicero, Frank Jr. (2018). "The Push for Statehood Begins". Creating the Land of Lincoln: The History and Constitutions of Illinois, 1778-1870. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252050343.

- ^ Cornelius, Janet (1972). Constitution making in Illinois, 1818-1970. University of Illinois Press. p. 6. ISBN 0252002512.

- ^ Cicero 2018, The Delegate Campaigns.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 13.

- ^ a b Railsback, Thomas F. (1968). "The Governor's Veto in Illinois". DePaul Law Review. 17 (3): 500.

- ^ Cicero 2018, The Convention Delegates Act Quickly.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, pp. 30, 35.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 30.

- ^ Fairlie, John A. (August 1917). "The Veto Power of the State Governor". The American Political Science Review. 11 (3). American Political Science Association: 479.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 35.

- ^ Cicero 2018, The Executive.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 50.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Railsback 1968, p. 501.

- ^ Cicero 2018, The Crucible of the Civil War.

- ^ Debel, N. H. (October 1916). "The Development of the Veto Power of the Governor of Illinois". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 9 (3). Illinois State Historical Society: 253.

- ^ Cornelius 1972, p. 68.

- ^ Debel 1916, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Railsback 1968, p. 505.

- ^ Fairlie 1917, p. 482 n.16.

- ^ a b Railsback 1968, p. 504.

- ^ Negley, Glenn R. (1939). "The Executive Veto in Illinois". American Political Science Review. 33: 1052. doi:10.2307/1948731.

- ^ Negley 1939, pp. 1053–1054.

- ^ Railsback 1968, p. 502.

- ^ Debel 1916, p. 255.

- ^ Fairlie 1917, p. 487 (citing Fergus v. Russell, 270 Ill. 304 (1915)).

- ^ House Committee on Rules (1986). Item Veto: State Experience and Its Application to the Federal Situation. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 13.

- ^ a b Cornelius 1972, p. 158.

- ^ Walters, John Nelson (1978). "The Illinois Amendatory Veto". John Marshall Journal of Practice & Procedure. 11 (2): 420.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 425.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 424.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 435.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 436.

- ^ Inlander, David W. (1974). "A Dilemma in Springfield: The Scope and Limitations of the Governor's Amendatory Veto Power in Illinois". Loyola University Chicago Law Journal. 5 (2): 394.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 437.

- ^ a b Walters 1978, p. 438.

- ^ Van Der Silk, Jack R. (1988). "Reconsidering the Amendatory Veto in Illinois". Northern Illinois University Law Review. 8: 767.

- ^ Lousin 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Walters 1978, p. 439.

- ^ Van Der Silk 1988, p. 770.

- ^ a b "Ill. Const. Art. 5 Sec. 11". Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Berry, Michael J. (2016). The Modern Legislative Veto: Macropolitical Conflict and the Legacy of Chadha. University of Michigan Press. p. 318 n.1. ISBN 9780472119776.

- ^ Falkoff, Marc D. (2016). "An Empirical Critique of JCAR and the Legislative Veto in Illinois" (PDF). DePaul Law Review. 65. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ "(5 ILCS 100/) Illinois Administrative Procedure Act". Illinois General Assembly. 5 ILCS 100/5-115. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Joint Committee on Administrative Rules. "About JCAR". Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ^ a b Illinois Legislative Reference Unit (2008). Preface to Lawmaking (PDF). Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- ^ Berry, Michael (2020). "Empowering legislatures: the politics of legislative veto oversight among the U.S. states". The Journal of Legislative Studies: 5. doi:10.1080/13572334.2020.1833133.

- ^ a b Falkoff 2016, p. 978.

- ^ a b c Davis, Shelley (June 1981). "Regulating regulations: JCAR". Illinois Issues. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Falkoff 2016, p. 981.

- ^ Berry 2016, p. 246.

- ^ a b Falkoff 2016, pp. 950–951.

- ^ a b "Forms of Counties". Illinois Association of County Board Members. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ^ "(55 ILCS 5/) Counties Code". Illinois General Assembly. 55 ILCS 5/2-5010. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ^ Petsche, Janet Northrop (1989). "County Home Rule: St. Clair, Dupage and Will Counties Have Opened the Door to Its Powers and Should Welcome Its Arrival". John Marshall Law Review. 22: 771.

- ^ Constitutional Convention Bulletin No. 11: Local Governments in Chicago and Cook County. Legislative Reference Bureau. 1920. p. 915.

- ^ "Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle Vetoes Plan To Release Addresses Of Confirmed COVID-19 Patients To First Responders". CBS News. 2020-05-26. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ "Kerner Addresses County Officials". Illinois State Register. 1961-08-16. p. 1 – via Newsbank.

- ^ "1-Man 1-Vote Will Change County Boards". Illinois State Register. 1969-05-02. p. 6 – via Newsbank.

- ^ "Senate Kills Bill on 'County Executive'". Illinois State Register. 1969-05-15 – via Newsbank.

- ^ Miller, David R. (2005). 1970 Illinois Constitution Annotated for Legislators (PDF) (4th ed.). p. 70. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Kanthak, John (1996-11-06). "R.I. County voters back winners: R.I. also backs Durbin, abolition of county post". Rock Island Argus. p. A14 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Andreoli, Tom (August 1990). "Will County executive: New office takes hold under Adelman". Illinois Issues. p. 45. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ "Office of the County Executive". Champaign County. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Pressey, Debra (2021-05-28). "Champaign County Board Democrats override veto of 'equity' map". The News-Gazette. Champaign, Illinois. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Ill. Jur. 21, § 12.34.

- ^ Simon, Adam B. (2014-04-29). "Manager Form of Government [Memorandum]" (PDF). Ancel Glink. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ^ a b Illinois Jurisprudence, Volume 21: Municipal Law. Matthew Bender & Co. § 6.67 Managerial form of government. ISBN 9781663343710.

- ^ Ill. Jur. 21, § 12.32.

- ^ "(65 ILCS 5/) Illinois Municipal Code". Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ^ Ill. Jur. 21, § 6.70.

- ^ 65 ILCS 20/21-15.

- ^ a b Ill. Jur. 21, § 12.36.

- ^ Reed, Thomas Harrison (1926). Municipal Government in the United States. Century Company. p. 68 n.3.

- ^ Blumm, Michael (2022). "The Public Trust Doctrine and the Chicago Lakefront". Michigan Journal of Environmental & Administrative Law. 11: 6 – via Lewis & Clark Law School Digital Commons.

- ^ Protess, David L. (2013). "Joseph Medill: Chicago's First Modern Mayor". In Green, Paul Michael; Holli, Melvin G. (eds.). The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition. SIU Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780809388455.

- ^ Teaford, Jon C. (2019). "The Respectable Rulers: Executive Officers and Independent Commissions". The Unheralded Triumph: City Government in America, 1870-1900. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421435251.

- ^ Nowlan, James D.; Gove, Samuel K; Winkel, Richard J. (2010). Illinois Politics: A Citizen's Guide. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252092015.

- ^ Newman, Katherine (2017-11-15). "Former Press Secretary Remembers His Time Inside Mayor Washington's Head". The Weekly Citizen. Citizen Newspaper Group.

- ^ Strausberg, Chinta (1986-08-11). "Mayor lauds power of the veto". Chicago Defender. p. 3 – via ProQuest.