Venice is a city in Sarasota County, Florida, United States. The city includes what locals call "Venice Island", a portion of the mainland that is accessed via bridges over the artificially created Intracoastal Waterway. The city is located in Southwest Florida.[8] As of the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 25,463,[9] up from 20,748 at the 2010 Census.[10] Venice is part of the North Port–Bradenton–Sarasota, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Venice, Florida | |

|---|---|

Venice's Beachfront from Humphris Park | |

| Nickname: Shark Tooth Capital of the World[1] | |

| Motto: "City on the Gulf"[2] | |

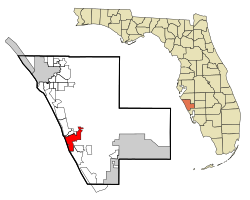

Location in Sarasota County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 27°6′N 82°26′W / 27.100°N 82.433°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Sarasota |

| Settled | |

| Incorporated |

|

| Named for | Venice, Italy |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Nick Pachota |

| • Vice mayor | Jim Boldt |

| Area | |

• City | 17.78 sq mi (46.05 km2) |

| • Land | 16.13 sq mi (41.77 km2) |

| • Water | 1.65 sq mi (4.28 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 25,463 |

• Estimate (2022) | 27,272 |

| • Density | 1,578.71/sq mi (609.54/km2) |

| • Metro | 833,716 (US: 71st) |

| • Metro density | 542.0/sq mi (209.3/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 34284–34287, 34290–34293 |

| Area code | 941 |

| FIPS code | 12–73900[6] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0292749[7] |

| Website | venicegov.com |

History

editThe area that is now Venice was originally the home of Paleo-Indians, with evidence of their presence dating back to 8200 BCE.[11] As thousands of years passed, and the climate changed and some of the Pleistocene animals that the Indians hunted became extinct, the descendants of the Paleo-Indians found new ways to create stone and bone weapons to cope with their changing environment. These descendants became known as the Archaic peoples. Evidence of their camps along with their stone tools were discovered in parts of Venice.[12] Over several millennia the culture and people who lived in the area changed. The peoples who the Spanish encountered when they arrived in 1500s were mound-builders. Venice lay in a boundary area between two cultures, the Tocobaga and the Calusa, and so you can find evidence of each in the area.[13]

The 1870s is when the area saw the first wave of white settlers.[3] Venice was first known as "Horse and Chaise" because of a carriage-like tree formation that marked the spot for fishermen.[3] During the 1870s, Robert Rickford Roberts established a homestead near a bay that bears his name today, Roberts Bay.[14] Francis H. "Frank" Higel, originally from France, arrived in Venice in 1883 with his wife and six sons. He purchased land in the Roberts' homestead for $2,500, equivalent to $82,000 in 2023[15], to set up his own homestead. Higel established a citrus operation involving the production of several lines of canned citrus items, such as jams, pickled orange peel, lemon juice, and orange wine.[16] Higel established a post office in 1885 with the name Eyry as a service for the community's thirty residents. In February he was appointed as postmaster but the office was shut down months later, in November 1885, with services moving back to Osprey. In 1888, another post office was established, this time with the name "Venice", a name Higel himself suggested because of its likeness to the canal city in Italy.[3][17][18]

During the Florida land boom of the 1920s, Fred H. Albee, an orthopedic surgeon renowned for his bone-grafting operations, bought 112 acres (45 ha) from Bertha Palmer to develop Venice.[14] He hired John Nolen to plan the city and create a master plan for the streets. Albee sold the land to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and retained Nolen as city planner. The first portions of the city and infrastructure were constructed in 1925–1926.[19]

In 1926, a fire department was formed with thirty-two volunteers. In that same year, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers purchased a new American LaFrance fire engine from Moore Haven that had been damaged in the Great Miami Hurricane.[20]

The first library was also founded in 1926 by the Venice-Nokomis Women's Club. This "library" was a few books on a shelf in a local store. The library had several temporary homes until 1965 when the Venice Area Public Library was built.[21][22] This building remained in use until it was demolished in 2017 due to mold. A new library was constructed in 2018 called the William H. Jervey Jr. Venice Library, named after a benefactor of the new building.[23]

On July 1, 1926, it was officially incorporated as the "Town of Venice", and soon after, on May 9, 1927, it officially became the "City of Venice".[4]

On October 9, 2024, Hurricane Milton made landfall just north of Venice, near Siesta Key, where Venice was near the ground zero of the hurricanes worst storm surge and high winds. Milton came less than two weeks after Hurricane Helene caused several feet of storm surge throughout the city of Venice.

Geography

editThe approximate coordinates for the City of Venice is located at 27°6′N 82°26′W / 27.100°N 82.433°W. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.6 square miles (43.1 km2), of which 15.3 square miles (39.5 km2) is land and 1.4 square miles (3.5 km2), or 8.19%, is water.[10] The climate of Venice is humid subtropical, bordering very closely on a tropical savanna climate, thus featuring pronounced wet and dry seasons.

Climate

editThe climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild winters. According to the Köppen climate classification, the City of Venice has a humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa).

| Climate data for Venice, Florida, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1927–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

89 (32) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

97 (36) |

91 (33) |

89 (32) |

100 (38) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 83.3 (28.5) |

84.1 (28.9) |

86.9 (30.5) |

90.1 (32.3) |

93.9 (34.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

95.5 (35.3) |

96.1 (35.6) |

94.8 (34.9) |

92.5 (33.6) |

88.1 (31.2) |

84.3 (29.1) |

96.9 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 72.4 (22.4) |

75.0 (23.9) |

77.9 (25.5) |

82.5 (28.1) |

87.3 (30.7) |

89.9 (32.2) |

91.5 (33.1) |

91.5 (33.1) |

90.0 (32.2) |

85.8 (29.9) |

80.0 (26.7) |

75.0 (23.9) |

83.2 (28.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 62.0 (16.7) |

64.6 (18.1) |

67.7 (19.8) |

72.5 (22.5) |

77.5 (25.3) |

81.4 (27.4) |

82.9 (28.3) |

83.1 (28.4) |

81.6 (27.6) |

76.6 (24.8) |

69.9 (21.1) |

64.9 (18.3) |

73.7 (23.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 51.6 (10.9) |

54.2 (12.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

62.5 (16.9) |

67.8 (19.9) |

72.9 (22.7) |

74.3 (23.5) |

74.7 (23.7) |

73.2 (22.9) |

67.5 (19.7) |

59.7 (15.4) |

54.8 (12.7) |

64.2 (17.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 34.3 (1.3) |

37.7 (3.2) |

42.9 (6.1) |

50.3 (10.2) |

59.1 (15.1) |

68.3 (20.2) |

70.8 (21.6) |

71.5 (21.9) |

68.6 (20.3) |

54.9 (12.7) |

46.2 (7.9) |

39.8 (4.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 23 (−5) |

26 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

38 (3) |

49 (9) |

56 (13) |

62 (17) |

65 (18) |

60 (16) |

36 (2) |

29 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

22 (−6) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.68 (68) |

2.00 (51) |

2.97 (75) |

2.47 (63) |

3.25 (83) |

7.81 (198) |

7.39 (188) |

8.34 (212) |

7.16 (182) |

3.35 (85) |

1.54 (39) |

2.31 (59) |

51.27 (1,302) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.5 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 12.2 | 14.9 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 8.1 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 107.3 |

| Source: NOAA[24][25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 309 | — | |

| 1940 | 507 | 64.1% | |

| 1950 | 727 | 43.4% | |

| 1960 | 3,444 | 373.7% | |

| 1970 | 6,648 | 93.0% | |

| 1980 | 12,153 | 82.8% | |

| 1990 | 16,922 | 39.2% | |

| 2000 | 17,764 | 5.0% | |

| 2010 | 20,748 | 16.8% | |

| 2020 | 25,463 | 22.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] | |||

| Race | Pop 2010[27] | Pop 2020[28] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 19,762 | 23,466 | 95.25% | 92.16% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 113 | 172 | 0.54% | 0.68% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 24 | 29 | 0.12% | 0.11% |

| Asian (NH) | 152 | 244 | 0.73% | 0.96% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian (NH) | 3 | 5 | 0.01% | 0.02% |

| Some other race (NH) | 14 | 62 | 0.07% | 0.24% |

| Two or more races/Multiracial (NH) | 129 | 540 | 0.62% | 2.12% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 551 | 945 | 2.66% | 3.71% |

| Total | 20,748 | 25,463 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 25,463 people, 12,521 households, and 6,810 families residing in the city.[29]

In 2020, there was a population of 25,41.2% of the population were under 5 years old, 6.4% were under 18 years old, and 61.9% was 65 years and older. 3,204 veterans lived in the city and 9.5% of the population were foreign born persons. 54.6% of the population were female persons.

In 2020, the median household income was $61,953 with a per capita income of $60,284. 6.8% of the population lived below the poverty threshold. 90.9% of the households had a computer and 81.3% had a broadband internet subscription.

As of the 2010 United States census, there were 20,748 people, 11,143 households, and 5,926 families residing in the city.[30]

Arts and culture

editAnnual cultural events

editVenice has been listed in several publications as being the "Shark's Tooth Capital of the World".[31] It hosts the Shark's Tooth Festival every year to celebrate the abundance of fossilized shark's teeth that can be found on its coastal shores.

Museums and other points of interest

editThe following structures and areas are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

- Armada Road Multi-Family District

- Blalock House

- Eagle Point Historic District

- Edgewood Historic District

- Hotel Venice

- House at 710 Armada Road South

- Johnson-Schoolcraft Building

- Levillain-Letton House

- Triangle Inn

- Valencia Hotel and Arcade

- Venezia Park Historic District

- Venice Depot

Theatre and music

edit- Venice Theatre is the largest per-capita community theater in the United States with an operating budget of almost three million dollars.[32]

Media

editVenice's newspaper is the Venice Gondolier Sun. It is published twice each week and has a circulation of 13,500 copies.[33][34]

Tampa Bay's Univision affiliate WVEA-TV is licensed to Venice, though it is based in Tampa and broadcasts from Riverview.

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editRoads

edit- I-75 – the only freeway in the area, I-75 runs through the mainly inland areas of the City of Venice.

- U.S. 41 (Tamiami Trail) – The Major North-South Route through the city.

- U.S. 41 Bypass (Venice Bypass) – Forms a Bypass Loop of Venice Island, and the City of Venice.

- State Road 681 – Venice Connector, this road was formerly the southern terminus of Interstate 75 in the early 1980s.

- County Road 762 (Laurel Road) – Runs East-West and connects US-41 to I-75 in the Northern Sections of the city.

- County Road 765 (Jacaranda Boulevard) - Runs North-South, skirting the Western City Limits, connecting I-75 to US-41, southwest of the city.

- County Road 772 (Venice Avenue) – The primary east-west Roadway in the city, CR 762 connects US-41 to US-41 Bypass and Jacaranda Blvd (CR-765).

Rail and Air

editPassenger railroad service, served by the Seaboard Coast Line, last ran to the station in 1971, immediately prior to the Amtrak assumption of passenger rail operation.[35] Previously Venice was one of the Florida destinations of the Orange Blossom Special.[36]

Travel to and from Venice by air is available two airports, Venice Municipal Airport located two miles from the central business district and is primarily used by chartered and private jets as well as small personal aircraft while domestic and international flights are available at Sarasota–Bradenton International Airport approximately thirty miles from Venice's central business district.

Law enforcement

editVenice is patrolled by the Venice Police Department. Tom Mattmuller is the current Chief of Police. The small department has special units for bike patrols, traffic patrols, and boat patrols, amongst the normal police services provided. There are a total of 73 members of the police department that serve Venice.[37]

Notable people

edit- Brian Aherne, English actor[38]

- Dri Archer, American football player [39]

- Trey Burton, American football player [40]

- Hector A. Cafferata Jr., United States Marine who received the Medal of Honor for his heroic service at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War[41]

- Walter Farley, author of The Black Stallion[42]

- Dick Hyman, jazz musician [43]

- Forrest Lamp, professional football player

- Alvin Mitchell, American football player [44][45]

- Tom Tresh, professional baseball player

- Steve Trout, former major league baseball pitcher

- Early Wynn, professional baseball player

See also

edit- Huffman Aviation, a flight school at Venice Municipal Airport which was attended by several of the hijackers of the September 11 attacks

- Kentucky Military Institute, which wintered in Venice for many years

- Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, whose Clown College originally was located in Venice, and whose winter headquarters used to be in Venice

- Tervis Tumbler, a United States drinkware manufacturer with headquarters and production in Venice

- Epiphany Cathedral (Venice, Florida), is a Roman Catholic cathedral located in Venice

- Venetian Waterway Park, is a 9.3-mile concrete trail located in Venice consisting of two parallel trails along the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) connected by two bridges.

References

edit- ^ "Authentic Florida: Venice, "Shark Tooth Capital of the World"". Visit Sarasota. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "Official Website of City of Venice, Florida". Official Website of City of Venice, Florida. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Venice Florida, United States". Britannica.

- ^ a b "Mayor History". www.venicegov.com.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Map of Southwest Florida".

- ^ US Census Bureau (September 24, 2021). "QuickFacts - Venice city, Florida". US Census Bureau - Quick Facts. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Venice city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Milanich, Jerald T. (February 1976). "Indians of North Central Florida". Florida Anthropologist. 31: 131–140.

- ^ Almy, Marion M. (September 1985). "An Archaeological Survey of Selected Portion of the City of Venice". City of Venice: unpublished manuscript prepared for Venice Historical Survey Committee. p. 7.

- ^ Mathews, Janet Snyder (2017). Venice: Journey from Horse and Chaise (2nd ed.). Sesquicentennial Productions Inc. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-9621986-0-1.

- ^ a b Angermann, Chris (February 16, 2013). "In Venice, an island of history and charm". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Early History". Venice, Florida. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Frank Higel was Entrepreneur and Pioneer". Sarasota History Alive!. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Deming, J., Schwarz, R., Carender, P., Delanaye, D., & Williams, J. Sarasota County Department of Historical Resources. (1990). An Historic Resources Survey of the Coastal Zone of Sarasota County, Florida. Department of Environmental Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CZIC-g70-215-c63-f6-1990/html/CZIC-g70-215-c63-f6-1990.htm

- ^ "The History of Venice, Fl: Preserving the Past". Visit Sarasota. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Mersereau, Jack (2014). Venice Fire Department: 1926-2011 85 Years of Service. Venice Heritage. p. 1. ISBN 9780983700210.

- ^ Ad-vantages (1979). An addition to the Venice Area Public Library. Venice, FL: Sun Coast Times, Inc.

- ^ "Sarasota County Library System". Florida Library History Project. 1998. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ Dean, Vicki (December 14, 2018). "Library benefactor reflects on philanthropy, investing in Venice". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Venice city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Venice city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2020: Venice city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "S1101 HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES - 2010: Venice city, Florida". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Profile for Venice, Florida, FL". ePodunk. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Venice Theatre History | Venice Theatre". Venice Theatre. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Venice Gondolier Sun". Venice Gondolier Sun. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Venice Gondolier Sun". Mondo Times. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Venice Train Depot | Sarasota History Alive!". Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Bowen, Eric H. "The Orange Blossom Special – December, 1941 – Streamliner Schedules". Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "Meet the Chief". www.venice.gov. City of Venice. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (August 19, 2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Palattella, Henry (March 2, 2020). "What the hell happened to Dri Archer?". Medium. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Levey-Baker, Cooper (January 3, 2019). "With the NFL Playoffs Looming, a Former Venice High Football Star Hopes for More Super Bowl Magic". Sarasota Magazine. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "Obituary: Hector A. Cafferata Jr. 1929 - 2016". Sarasota Herald Tribune. April 15, 2016.

- ^ About Walter Farley: The Black Stallion. The Black Stallion | Black Stallion Ranch - The Official Fan Site By Tim Farley. (2017, May 10). Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://theblackstallion.com/web/author/

- ^ Feinman, M. (Spring 2012). A Conversation with Dick Hyman. Saw Palm, 6, 97-99. Retrieved from http://www.sawpalm.org/uploads/6/6/2/8/6628902/saw_palm_-_volume_6_-_2012.pdf on 2 February 2022.

- ^ "ALVIN MITCHELL". profootballarchives.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ "Alvin Mitchell". Trading Card Database. Retrieved February 4, 2022.