Vedrana Rudan (born 29 October 1949) is a Croatian journalist and novelist.

Vedrana Rudan | |

|---|---|

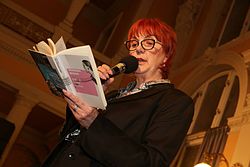

Vedrana Rudan in 2015 | |

| Born | 29 October 1949 Opatija, PR Croatia, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Occupation | Writer, journalist |

| Language | Croatian |

| Nationality | Croat |

| Spouse | Ljubiša Drageljević |

Biography

editVedrana Rudan was born in Opatija, Yugoslavia in 1949. She graduated from the Teacher Training College in Rijeka with a degree in Croatian and German languages. She worked as a teacher, tourist guide, a writer for several Croatian newspapers (Feral Tribune, Slobodna Dalmacija, Novi list, Jutarnji list),[1] and as a journalist for the state radio.

In 1991, she was fired from her job at Radio Rijeka for her criticism of the president, Franjo Tuđman.[2] After her husband was laid off from his job, they opened a real-estate agency.[3] Although a final court verdict was in her favour, she was prevented from returning to her job.[citation needed] She wrote for Nacional, Croatia's biggest newspaper, until 2011.[3][4]

From 2010 to 2015, she wrote about everyday themes on her very widely read blog called "How to Die Without Stress" ("Kako umrijeti bez stresa"). She stopped writing her blog on 21 August 2015 as "all that we write about is hatred. I do not know anymore where we are, whether we are in 2015, 1991 or 1941. There is still an active hunt on Serbs going on all wrapped up in a struggle for the right of the Croatian nation. Right for what? Hunger, misery, loans?"[5] Her last post "I Give Up" ("Odustajem") was read around 50,000 times.[6]

In 2017, she has signed the Declaration on the Common Language of the Croats, Serbs, Bosniaks and Montenegrins.[7]

Literary career

editHaving lost her journalism job, Rudan began writing fiction. Her first novel, Uho, grlo, nož, came out in 2002. A plotless monologue by an embittered and unhappily married woman, Tonka Babić, it was well-received for its feminist theme and strident, furious voice.[8] Her second book, Ljubav na posljednji pogled (2003), was a powerful plaint against marital abuse, written from her own experience of her first marriage. Rudan explained that she wrote it as a catharsis, and to encourage other women in the same position, but added that the trauma experienced by an abused woman could hardly be cured by one book.[9]

By the time of her third book, Crnci u Firenci (2006), Rudan had established herself as a polemicist and controversial author. The alternating points of view of the narrators, all members of an extended Rijeka household, were a new development in the complexity of Rudan's work, and the linked monologues were compared to the film American Beauty.[10] But while she was able to portray each of her narrators convincingly, there was little to distinguish between them.[11]

Rudan's next book, Kad je žena kurva, kad je muškarac peder (2008), was a compilation of columns originally published in the weekly Nacional. In them, she continued to deal with issues such as violence against women, machismo, imposed patterns of behaviour in traditional society, political corruption, and poverty. In 2014, the book was adapted for the stage as Kurva (Whore), directed by Zijah Sokolović, which was lauded as a mix of shocking, happy, tragic, bizarre and realistic tones, and captured Rudan's distinctive voice.[12]

In her 2010 book, Dabogda te majka rodila, she turned her attention to the fraught relationship between mothers and daughters. Once again, this book was based on her own experience. She and her mother were not always as close as they might have been; she felt guilt and anguish when her mother died; and felt daily that her mother was still watching and judging her and finding her wanting.[9]

Controversies

editRudan has been accused of antisemitism twice. In a column in Nacional, she complained that Croatian Jews condemn some right-wing nationalists as fascists while condoning others who have close ties with Israel.[13] In 2009, Rudan made statements during International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Nova TV, comparing the situation in Gaza to the Holocaust. She was subsequently dismissed from further appearances in the network, for which she claimed the reason was that the owner of Nova TV belonged to the World Jewish Council.[14][15]

In 2011, Rudan was laid off from Nacional for calling the Catholic Church "a criminal organisation".[16]

Personal life

editRudan is married to Ljubiša Drageljević, a lawyer, and lives in Rijeka. She has a son Slaven and a daughter Asja from her first marriage.[17][18]

Rudan recounted the marital abuse from her first husband over fourteen years of marriage. She began her relationship with Drageljević while she was still married.[9]

Bibliography

edit- Uho, grlo, nož (Ear, Throat, Knife) (2002) – (Night. Translated by Celia Hawkesworth. Dalkey Archive Press. 2004. ISBN 978-1-56478-347-9.)

- Ljubav na posljednji pogled (Love at Last Sight) (2003)

- Ja, nevjernica (I, Unbeliever) (2005)

- Crnci u Firenci (Blackmen in Florence) (2006)

- Kad je žena kurva / kad je muškarac peder (When Woman Is a Whore / When Man Is a Faggot) (2008)

- Strah od pletenja (Fear of Knitting) (2009)

- Dabogda te majka rodila (May Your Mother Give Birth to You) (2010)

- Kosturi okruga Madison (Skeletons of Madison County) (2012)

- U zemlji krvi i idiota (In a Land of Blood and Idiots) (2013)

- Amaruši (Amaruši) (2013)

- Zašto psujem (Why I Curse) (2015)

- Muškarac u grlu (Man in the Throat) (2016)

- Život bez krpelja (Life Without Ticks) (2018)

- Ples oko sunca, autobiografija (Dancing Around the Sun, an Autobiography) (2019)

- Dnevnik bijesne domaćice, predgovor novom izdanju (Diary of a Mad Housewife, a Preface to the New Edition) (2020)

- Puding od vanilije (Vanilla Pudding) (2021)

- Doživotna robija (Imprisoned for Life) (2022)

- Besplatna dostava (Free delivery) (2023)

References

edit- ^ Begagić, Lamija (August 10, 2005). "Rudan, Vedrana" (in Czech). iLiteratura.cz. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Mark (1999). Forging War: The Media in Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina. University of Luton Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-86020-552-1.

- ^ a b Lucic, Ana. "An Interview with Vedrana Rudan". Dalkey Archive Press.

- ^ "Vedrana Rudan: Archives". Nacional (in Croatian). Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ "Vedrana Rudan prestala pisati blog: Ne mogu podnijeti mržnju koja vlada Hrvatskom - black". Index.hr. August 24, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "Odustajem | Vedrana Rudan". Rudan.info. August 24, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Derk, Denis (March 28, 2017). "Donosi se Deklaracija o zajedničkom jeziku Hrvata, Srba, Bošnjaka i Crnogoraca" [A Declaration on the Common Language of Croats, Serbs, Bosniaks and Montenegrins is About to Appear]. Večernji list (in Serbo-Croatian). Zagreb. pp. 6–7. ISSN 0350-5006. Archived from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Lacey, Josh (December 11, 2004). "Bitter somethings". The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Drinjaković, Mersiha (July 9, 2010). "Muškarci ne vole dobre žene". Gracija (in Bosnian). Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ Pogačnik, Jagna (May 25, 2006). "Vedrana Rudan – "Crnci u Firenci"". Moderna vremena. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ "bijela vrana poet grakće" (in Croatian). Kupus.net. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ Parać, Zvonimir (November 11, 2014). ""Kurva" napokon dolazi u Split!" (in Croatian). S4S Portal. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (July 2, 2007). "Fascist Overtones From Blithely Oblivious Rock Fans". The New York Times.

- ^ Croatia: International Religious Freedom Report 2009 (Report). U.S. Department of State. October 26, 2009.

- ^ "Vedrana Rudan's Statement is Pure Anti-Semitism". Zagreb: Dalje. January 28, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Croatian Writer Rudan Dismayed by State of Society". Misli. March 27, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Marjanović, Vera (April 10, 2015). "Vedrana Rudan: "Jugoslawien ist lebendiger denn je"" (in German). Kosmo. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Trošelj, Slavko (December 18, 2011). "Uživam dva ugleda" (in Serbian). Politika. Retrieved June 23, 2015.