Archival research is a type of research which involves seeking out and extracting evidence from original archival records. These records may be held either in institutional archive repositories, or in the custody of the organization (whether a government body, business, family, or other agency) that originally generated or accumulated them, or in that of a successor body. Archival research can be contrasted with (1) secondary research (undertaken in a library or online), which involves identifying and consulting secondary sources relating to the topic of enquiry; and (2) with other types of primary research and empirical investigation such as fieldwork and experiment.

Archival research lies at the heart of most academic and other forms of original historical research; but it is frequently also undertaken (in conjunction with parallel research methodologies) in other disciplines within the humanitiesand social sciences, including literary studies, archaeology, sociology, human geography, anthropology, and psychology. It may also be important in other non-academic types of enquiry, such as the tracing of birth families by adoptees, and criminal investigations.

History of archival research

editThe oldest archives have been in existence for hundreds of years. For instance, the Vatican Secret Archives was started in the 17th century AD and contains state papers, papal account books, and papal correspondence dating back to the 8th century. Many national archives were established over a century ago and contain collections going back several hundred years or more. The United States National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) was established originally in 1934.[1] The NARA contains records and collections dating back to the founding of the United States in the 18th century. Among the collections of the NARA are the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and an original copy of the Magna Carta. Similarly, the Archives nationales in France was founded in 1790 during the French Revolution and has holdings that date back to AD 625.[2][3]

Universities are another historic venue for archival holdings. Most universities have archival holdings that chronicle the business of the university. Some universities also have cultural archives that focus on one aspect or another of the culture of the state or country in which the university is located. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has archival collections on the subjects of Southern History and Southern Folklife.[4] Boston University's Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Library has collections dedicated to chronicling advances and famous moments in American art, drama, and public/political life.[5]

The reason for highlighting the breadth and depth of historical archives is to give some idea of the difficulties facing archival researchers in the pre-digital age. Some of these archives were dauntingly vast in the quantity of records they held. For example, The Vatican Secret Archive had upwards of 52 miles of archival shelving. In an age where you could not simply enter your query into a search bar complete with Boolean operators the task of finding material that pertained to your topic would have been difficult at the least. The Finding aid made the work of sifting through these vast archives much more manageable.[6] A finding aid is a document that is put together by an archivist or librarian that contains information about the individual documents in a specific collection in an archive. These documents can be used to determine if the collection is relevant to a designated topic. Finding aids made it so a researcher did not have to blindly search through collection after collection hoping to find pertinent information. However, in the pre-digital age a researcher still had to travel to the physical location of the archive and search through a card catalog of finding aids.

Researching at an archive

editDiscovery

editArchival research is generally more complex and time-consuming than library and internet research, presenting challenges in identifying, locating and interpreting relevant documents. Archival records are often unique, and the researcher must be prepared to travel to reach them. Even if materials are available in digital formats there may be restrictions, such as copyright or donor agreements, that prohibit them from being accessed off-site.

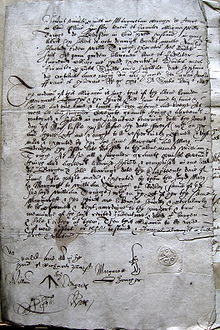

Finding aids are a common reference tool created by archivists for locating materials. Some finding aids to archival documents are hosted online, but many are not, and some records lack any kind of finding aid at all. Although most archive repositories welcome researchers, and have professional staff tasked with assisting them, the sheer quantity of records means that finding aids may be of only limited usefulness: the researcher will need to hunt through large quantities of documents in search of material relevant to his or her particular enquiry. Some records may be closed to public access for reasons of confidentiality; and others may be written in archaic handwriting, in ancient or foreign languages, or in technical terminology. Archival documents were generally created for immediate practical or administrative purposes, not for the benefit of future researchers, and additional contextual research may be necessary to make sense of them. Many of these challenges are exacerbated when the records are still in the custody of the generating body or in private hands, where owners or custodians may be unwilling to provide access to external enquirers, and where finding aids may be even more rudimentary or non-existent.

Special Materials

editRestrictions

editOn-Site

editThe unique, fragile, or sensitive nature of some materials requires the enforcement of certain kinds of restrictions on their use, handling, and duplication. Many archives restrict what kinds of items can be brought into a reading room, such as bags, notepads, and pencils. Further restrictions may be placed on the number of materials that can be consulted at any given time, such as limiting a user to one box at a time and requiring all materials to be laid flat and visible at all times.[7] Some archives provide basic supplies including scrap paper and pencils or foam wedges for supporting unusually large materials.[8]

Sensitive Materials

For social science researchers in particular, concerns regarding the privacy and confidentiality of information contained in materials, such as medical and student records, demand special care. Some require agreements with the archives that any personally identifiable information, such as social security numbers and names, must be scrubbed, or that the information must be anonymized.

Services

editElectronic and digital materials

editIntroduction

Pre-Internet data storage

editOrganizing, collecting, and archiving information using physical documents without the use of electronics is a daunting task. Magnetic storage devices provided the first means of storing electronic data. As technology has progressed over the years, so too has the ability to archive data using electronics. Long before the Internet, means of using technology to help archive information were in the works. The early forms of magnetic storage devices that would later be used to archive information were invented as early as the late 19th century, but were not used for organizing information until 1951 with the invention of the UNIVAC I.

UNIVAC I, which stands for Universal Automatic Computer 1, used magnetic tape to store data, and was the first commercial computer produced in the United States. Early computers such as UNIVAC I were enormous and sometimes took up entire rooms, rendering them completely obsolete in today's technological society. But the central idea of using magnetic tape to store information is a concept that is still in use today.

While most magnetic storage devices have been replaced by optical storage devices such as CDs and DVDs, some are still in use today.[9] In fact, the floppy drive is one example of a magnetic storage device that became extremely popular in the 1970s through the 1990s. Floppy disks have for years been used by millions of people to back-up the information on their hard drives.

Magnetic tape has proven to be a very effective means of archiving data as large amounts of data that don’t need to be quickly accessed can be found on magnetic tape. That is especially true of aging data that may not need to be accessed again at all, but for different reasons still needs to be stored “just in case”.[9] However the longevity and stability of magnetic tape is not fully understood with upper limits of around thirty years for many common tape formats.[10]

Internet-age archiving

editWith the development of the Internet in recent decades, archiving has begun to make its way online. The days of using electronic devices such as magnetic tape are coming to an end as people start to use the internet to archive their information.

Internet archiving has become extremely popular for several reasons. As mentioned earlier, the attempt to have as much information take up as little space as possible is very helpful for many archivists. Using the Internet to archive allows for this to be possible as well as many other benefits. Internet archiving can be used to store as little information needed for a single person, or for as much information needed for a major company. Internet archives can contain large-scale digitization as well as provide long term management and preservation of the digital resources similar to the electronics used in the pre-Internet data storage era.

Along with the idea of storage benefits, archiving via Internet ensures that ones information is safe. There is risk of misplacing your information, or having it get destroyed by water or fire etc. Those are problems that may occur when archiving using floppy discs, hard drives, and computers. Lastly, the ability to access the information from almost anywhere is one of the main attractions to online archiving. As long as one has access to the Internet they can edit and retrieve the information they are looking for.

Most institutions with physical archives have begun to digitize their holdings and make them available on the Internet. Notably the National Archive and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. has a clearly defined initiative that was started in 1998 in an attempt to digitize many of their holdings and make them available on the Internet.[11]

In February 1997, key figures from the academic, archival, corporate, government, legal, and technology communities came together for the first time at a groundbreaking conference in San Francisco. The conference, “Documenting the Digital Age,” was sponsored by the National Science Foundation, MCI Communications Corporation, Microsoft Corporation, and History Associates Incorporated, and was a special initiative to discuss the preservation of electronic records.[12]

Research methodologies

editJust as there are many kinds of archives, there are also many methodologies for using archives to conduct research. Some of them depend on the archive or materials themselves while others are determined or influenced by discipline and field. For example, academic historians and students may find benefits in consulting directly with archive staff who may have a clear understanding of collections and their organization. Further, archive staff can be a source of information regarding unprocessed materials or know of other materials in related archives. For other kinds of researchers, such as genealogists, their methodology may rely more upon formal or informal networks of other genealogists to support research by sharing information about specific archives' organization and collections.

References

edit- ^ [Archive.gov. National Records and Archive Administration, 1 December 2009. Web. 5 December 2009 <https://www.archives.gov/research/start/>.]

- ^ France, Archives nationales. "Accueil". www.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/ (in French). Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ France, Archives nationales. "Accueil". www.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/ (in French). Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ [The Louis Round Wilson Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 20 November 2009. Web. 4 December 2009 <http://www.lib.unc.edu/wilson/>.]

- ^ Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center, 01 Dec. 2009. Web. 05 Dec. 2009 <http://www.bu.edu/dbin/archives/index.php?pid=401>.

- ^ [University of Toronto Library Glossary. University of Toronto, 15 November 2009. Web. 4 December 2009 <http://www.library.utoronto.ca/utarms/info/glossary.html>.]

- ^ "Regulations for NARA Researchers". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Ramsey, Alexis; Sharper, Wendy; L'Eplattenier, Barbara; Mastrangelo, Lisa (2010). "Archival Survival: Navigating Historical Research". Working in the Archives: Practical Research Methods for Rhetoric and Composition. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780809329502.

- ^ a b (2009). Data Storage. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2009, from Directory M articles, Articles. DirectoryM.com 100 Franklin St, 9th Floor Boston, MA 02110. Web site: http://articles.directorym.com/Data_Storage-a486.html.

- ^ "4. Life Expectancy: How Long Will Magnetic Media Last? • CLIR". CLIR. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^ Building an electronic records archive at the National Archives and Records Administration recommendations for a long-term strategy. Washington, D.C: National Academies, 2005. Print.

- ^ "Documenting The Digital Age". History Associates. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

External links

edit- National Archives and Records Administration [1]

- Trace Your Birth Family In The UK https://web.archive.org/web/20150218205915/http://ukadoptionregister.org/

- "Archive skills and tools for historians" - Making History (Institute of Historical Research, University of London)

Category:Archives

Category:Documents

Category:Historiography

Category:Research methods