This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Uilta (Orok: ульта, also called Ulta, Ujlta,[a] or Orok) is a Tungusic language spoken in the Poronaysky and Nogliksky Administrative Divisions of Sakhalin Oblast, in the Russian Federation, by the Uilta people. The northern Uilta who live along the river of Tym’ and around the village of Val have reindeer herding as one of their traditional occupations. The southern Uilta live along the Poronay near the city of Poronaysk. The two dialects come from the northern and eastern groups, however, they have very few differences.

| Uilta | |

|---|---|

| Orok | |

| ульта | |

| Native to | Russia, Japan |

| Region | Sakhalin Oblast (Russian Far East), Hokkaido |

| Ethnicity | 300 Orok (2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 116 (2020 census)[2] |

| Cyrillic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | oaa |

| Glottolog | orok1265 |

| ELP | Orok |

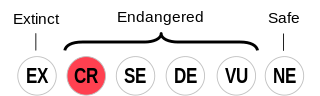

Orok is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Classification

editUilta is closely related to Nanai, and is classified within the southern branch of the Tungusic languages. Classifications which recognize an intermediate group between the northern and southern branch of Manchu-Tungus classify Uilta (and Nanai) as Central Tungusic. Within Central Tungusic, Glottolog groups Uilta with Ulch as "Ulchaic", and Ulchaic with Nanai as "Central-Western Tungusic" (also known[by whom?] as the "Nanai group"), while Oroch, Kilen and Udihe are grouped as "Central-Eastern Tungusic".[4]

Distribution

editAlthough there has been an increase in the total population of the Uilta there has been a decrease in people who speak Uilta as their mother tongue. The total population of Uiltas was at 200 in the 1989 census of which 44.7, then increased to approximately 300–400 persons. However, the number of native speakers decreased to 25–16 persons. According to the results of the Russian population census of 2002, Uilta (all who identified themselves as "Oroch with Ulta language", "Orochon with Ulta language", "Uilta", "Ulta", "Ulch with Ulta language" were attributed to Uilta) count 346 people, 201 of whom are urban and 145 of whom are village dwellers. The percentage of 18.5%, which is 64 people pointed that they have a command of their ("Ulta") language, which, mostly, should be considered as a result of increased national consciousness in the post-Soviet period than a reflection of the real situation. In fact, the number of those people with a different degree of command of the Uilta language is less than 10 and the native language of the population is overwhelmingly Russian. Therefore because of the lack of a practical writing system and sufficient official support the Uilta language has become an endangered language.

The language is critically endangered or moribund. According to the 2002 Russian census there were 346 Uilta living in the north-eastern part of Sakhalin, of whom 64 were competent in Uilta. By the 2010 census, that number had dropped to 47. Uilta also live on the island of Hokkaido in Japan, but the number of speakers is uncertain, and certainly small.[5] Yamada (2010) reports 10 active speakers, 16 conditionally bilingual speakers, and 24 passive speakers who can understand with the help of Russian. The article states that "It is highly probable that the number has since decreased further."[6]

Uilta is divided into two dialects, listed as Poronaisk (southern) and Val-Nogliki (northern).[4] The few Uilta speakers in Hokkaido speak the southern dialect. "The distribution of Uilta is closely connected with their half-nomadic lifestyle, which involves reindeer herding as a subsistence economy."[7] The Southern Uilta people stay in the coastal Okhotsk area in spring and summer, and move to the North Sakhalin plains and East Sakhalin mountains during fall and winter. The Northern Uilta people live near the Terpenija Bay and the Poronai River during spring and summer and migrate to the East Sakhalin mountains for autumn and winter.

Research

editTakeshiro Matsuura (1818–1888), a prominent Japanese explorer of Hokkaido, southern Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands, was the first to make a notable record of the language. Matsuura wrote down about 350 Uilta words in Japanese, including about 200 words with grammatical remarks and short texts. The oldest set of known records[clarification needed] of the Uilta language is a 369-entry collection of words and short sample sentences under the title "Worokkongo", dating from the mid-nineteenth century.[citation needed] Japanese researcher Akira Nakanome, during the Japanese possession of South Sakhalin, researched the Uilta language and published a small grammar with a glossary of 1000 words. Other researchers who published some work on the Uilta were Hisharu Magata, Hideya Kawamura, T.I Petrova, A.I Novikova, L.I Sem, and contemporary specialist L.V. Ozolinga. Magata published a substantial volume of dictionaries called "A Dictionary of the Uilta Language / Uirutago Jiten" in 1981. Others contributing to Uilta scholarship were Ozolinga, who published two substantial dictionaries: one in 2001 with 1200 words, and one in 2003 with 5000 Uilta-Russian entries and 400 Russian-Uilta entries.

Phonology

editInventory

edit| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n[i] | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ[ii] | |

| Fricative | s[iii] | x | |||

| Tap | ɾ[iv] | ||||

| Approximant | l[iv] | j | w | ||

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | ɵ ~ o | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ[i] | ə | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

- ^ /ɛ/ occurs most often in the diphthong /ɛu/ or as the long vowel /ɛɛ/. The short monophthong /ɛ/ rarely occurs on its own.

Uilta has constrastive vowel length.

Phonotactics

editSyllable structure

editUilta has a (C)V(V)(C)[b] syllable structure.[10] Monosyllabic words always contain either a diphthong or a long vowel, thus no words have the structure *(C)V(C).[10] All consonants may occur both syllable initial and syllable final, however /ɾ/ may not occur word initial, and /m/, /n/ and /l/ are the only consonants that can be word final[c], with /m/ and /n/ only being permitted to be word final in monosyllabic words.[10]

Morae

editSyllables can be further divided into morae which determine stress and timing of the word.[11] The primary mora of a syllable consists of the vowel and the initial consonant if there is one.[11] After the primary mora an additional each vowel or consonant in the syllable form secondary morae.[11] Any word typically contains a minimum of two morae.[11]

Pitch accent

editUilta has non-phonemic pitch accent.[12] Certain morae are accented with higher pitch. High pitch begins on the second mora[d] and ends on the accent peak.[12] The accent peak falls on the second to last mora if it is primary and the closest preceding primary mora otherwise.[12]

For example pa.ta.la (transl. girl) is made of three syllables each consisting of one primary mora. Thus the accent peak falls on ta, the penultimate mora. In ŋaa.la (transl. hand), there are two syllables and three morae, the penultimate mora is a a secondary mora, so the accent peak falls on the previous mora, ŋa.

Vowel harmony

editWords in Uilta exhibit vowel harmony.[13] Uilta vowels can be divided into three groups based on how they interact with vowel harmony:[13]

- Close: /ə/ /ɵ/

- Neutral: /i/ /ɛ/ /u/

- Open: /a/ /ɔ/

Close and open vowels cannot coexist with each other in the same word.[13] Neutral vowels have no restrictions and can occur in words with close vowels, open vowels or other neutral vowels.[13]

Orthography

editA Cyrillic alphabet was introduced in 2007. A primer has been published, and the language is taught in one school on the island of Sakhalin.[14][failed verification]

| А а | А̄ а̄ | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Е̄ е̄ |

| Ӡ ӡ | И и | Ӣ ӣ | Ј ј | К к | Л л | М м | Н н |

| Ԩ ԩ | Ӈ ӈ | О о | О̄ о̄ | Ө ө | Ө̄ ө̄ | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ӯ ӯ | Х х | Ч ч | Э э | Э̄ э̄ |

The letter U+0528 Ԩ CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER EN WITH LEFT HOOK has been included in Unicode[15] since version 7.0.[citation needed]

In 2008, the first Uilta primer was published, which established a writing system.[3]

Morphology

editThis section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Data and examples are not properly integrated into the text. "Table" is not properly formatted. (October 2021) |

The Uilta language is formed by elements called actor nouns.[clarification needed] These actor nouns are formed when a present participle is combined with the noun – ɲɲee. For example, the element – ɲɲee (< *ɲia), has become a general suffix for 'humans', as in ǝǝktǝ-ɲɲee ‛woman’, geeda-ɲɲee ‛one person’ and xasu-ɲɲee ‛how many people?’. Much of what constitutes Uilta and its forms[clarification needed] can be traced back to the Ulch language.[dubious – discuss]

Uilta has participial markers for three tenses: past -xa(n-), present +ri, and future -li. When the participle of an uncompleted action, +ri, is combined with the suffix -la, it creates the future tense marker +rila-. It also has the voluntative marker (‘let us…!’) +risu, in which the element -su diachronically represents the 2nd person plural ending. Further forms were developed that were based on +ri: the subjunctive in +rila-xa(n-) (fut-ptcp.pst-), the 1st person singular optative in +ri-tta, the 3rd person imperative in +ri-llo (+ri-lo), and the probabilitative[clarification needed] in +ri-li- (ptcp.prs-fut).

In possessive forms, if the possessor is human, the suffix -ɲu is always added following the noun stem.[citation needed] The suffix -ɲu indicates that the referent is an indirect or an alienable possessee. To indicate direct and inalienable possession, the suffix -ɲu is omitted. For example,

- ulisep -ɲu- bi 'my meat' vs. ulise-bi 'my flesh'

- böyö -ɲu- bi 'my bear' vs. ɲinda-bi 'my dog'

- sura – ɲu – bi 'my flea' vs. cikte-bi 'my louse'

- kupe – ɲu – bi 'my thread' vs. kitaam-bi 'my needle'

Pronouns are divided into four groups: personal, reflexive, demonstrative, and interrogative. Uilta personal pronouns have three persons (first, second, and third) and two numbers (singular and plural). SG – PL 1st bii – buu 2nd sii – suu 3rd nooni – nooci. [3] [16]

Syntax

editNoun phrases have the following order: determiner, adjective, noun.

Tari

DET

goropci

ADJ

nari

N

That old man.

Eri

DET

goropci

ADJ

nari

N

‘This old man.’

Arisal

DET

goropci

ADJ

nari-l

N

‘Those old men’.

Subjects precede verbs:

Bii

S

xalacci-wi

V

‘I will wait’.

ii bii

S

ŋennɛɛ-wi

V

‘Yes, I will go’.

With an object the order is SOV:

Sii

S

gumasikkas

O

nu-la

V

‘You have money’.

Adjectives go after their noun:

tari

DET

nari caa

S

ninda-ji

N

kusalji

ADJ

tuksɛɛ-ni

V

‘That man runs faster than that dog’.

A sentence where the complement comes after its complement is a postposition:[clarification needed]

Sundattaa

N

dug-ji

N

bii-ni

Post

‘The fish (sundattaa) is at home (dug-ji)’.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Uilta may come from the word ulaa which means 'domestic reindeer'.[3]

- ^ C represents a position to be filled with a consonant, V represents a position to be filled with a vowel and parentheses indicate that a position is optional. Long vowels fill two vowel positions, i.e. VV is either a diphthong or a long vowel and V is always a short monophthong.

- ^ Consonants other than /m/, /n/ and /l/ may occur word finally in words of onomatopoeic origin.

- ^ Except when the accent peak falls on the first mora, in which case only the accent peak has high pitch.

References

edit- ^ Lewis, M. Paul; Gary F. Simons; Charles D. Fennig, eds. (2015). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (18th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ 7. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОСТЕЙ ПО РОДНОМУ ЯЗЫКУ

- ^ a b c Tsumagari (2009)

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Orok". Glottolog 4.3.

- ^ Novikova, 1997

- ^ Yamada (2010), p. 70

- ^ Yamada (2010), p. 60

- ^ Tsumagari (2009:2)

- ^ Tsumagari (2009:2–3)

- ^ a b c Tsumagari (2009:3)

- ^ a b c d Tsumagari (2009:3)

- ^ a b c Tsumagari (2009:3–4)

- ^ a b c d Tsumagari (2009:3)

- ^ Уилтадаирису (in Russian; retrieved 2011-08-17) ("UZ Forum – Language Learners Community". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.)

- ^ Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF)

- ^ Pevnov, Alexandr (2016). "On the Specific Features of Uilta as Compared with the Other Tungusic Languages". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 117: 47–63.

- Tsumagari, Toshiro (2009). "Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised)" (PDF). Journal of the Graduate School of Letters. 4: 1–21. hdl:2115/37062.

Further reading

edit- Majewicz, A. F. (1989). The Oroks: past and present (pp. 124–146). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Pilsudski, B. (1987). Materials for the study of the Orok [Uilta] language and folklore. In, Working papers / Institute of Linguistics Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu.

- Matsumura, K. (2002). Indigenous Minority Languages of Russia: A Bibliographical Guide.

- Kazama, Shinjiro. (2003). Basic vocabulary (A) of Tungusic languages. Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim Publications Series, A2-037.

- Yamada, Yoshiko (2010). "A Preliminary Study of Language Contacts around Uilta in Sakhalin". Běifāng rénwén yánjiū / Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities. 3: 59–75. hdl:2115/42939.

- Tsumagari, T. (2009). Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised). Journal of the Graduate School of Letters, 41–21.

- Ikegami, J. (1994). Differences between the southern and northern dialects of Uilta. Bulletin of the Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples, 39–38.

- Knüppel, M. (2004). Uilta Oral Literature. A Collection of Texts Translated and Annotated. Revised and Enlarged Edition . (English). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 129(2), 317.

- Smolyak, A. B., & Anderson, G. S. (1996). Orok. Macmillan Reference USA.

- Missonova, L. (2010). The emergence of Uil'ta writing in the 21st century (problems of the ethno-social life of the languages of small peoples). Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie, 1100–115.

- Larisa, Ozolinya. (2013). A Grammar of Orok (Uilta). Novosibirsk Pablishing House Geo.

- Janhunen, J. (2014). On the ethnonyms Orok and Uryangkhai. Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, (19), 71.

- Pevnov, A. M. (2009, March). On Some Features of Nivkh and Uilta (in Connection with Prospects of Russian-Japanese Collaboration). In サハリンの言語世界: 北大文学研究科公開シンポジウム報告書= Linguistic World of Sakhalin: Proceedings of the Symposium, 6 September 2008 (pp. 113–125). 北海道大学大学院文学研究科= Graduate School of Letters, Hokkaido University.

- Ikegami, J. (1997). Uirutago jiten [A dictionary of the Uilta language spoken on Sakhalin].

- K.A. Novikova, L.I. Sem. Oroksky yazyk // Yazyki mira: Tunguso-man'chzhurskie yazyki. Moscow, 1997. (Russian)