Dragon 2 is a class of partially reusable spacecraft developed, manufactured, and operated by American space company SpaceX for flights to the International Space Station (ISS) and private spaceflight missions. The spacecraft, which consists of a reusable space capsule and an expendable trunk module, has two variants: the 4-person Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon, a replacement for the Dragon 1 cargo capsule. The spacecraft launches atop a Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket, and the capsule returns to Earth through splashdown.[5]

| |

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

|---|---|

| Designer | SpaceX |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Operator | SpaceX |

| Applications | ISS crew and cargo transport; private spaceflight |

| Website | spacex.com/vehicles/dragon |

| Specifications | |

| Spacecraft type | Capsule |

| Launch mass | 12,500 kg (27,600 lb)[3][a] |

| Dry mass | 7,700 kg (16,976 lb)[4] |

| Payload capacity | |

| Crew capacity |

|

| Volume |

|

| Power |

|

| Batteries | 4 × lithium polymer |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Design life | |

| Dimensions | |

| Height | |

| Diameter | 4 m (13 ft)[5] |

| Width | 3.7 m (12 ft)[9] |

| Production | |

| Status | Active |

| Built | 13 (7 crew, 3 cargo, 3 prototypes) |

| Operational | 9 (5 crew, 3 cargo, 1 prototype) |

| Retired | 3 (1 crew, 2 prototypes) |

| Lost | 1 (crew, during uncrewed test) |

| Maiden launch |

|

| Related spacecraft | |

| Derived from | SpaceX Dragon 1 |

| Launch vehicle | Falcon 9 Block 5 |

| Thruster details | |

| Propellant mass | 2,562 kg (5,648 lb)[4] |

| Powered by |

|

| Maximum thrust |

|

| Specific impulse | Draco: 300 s (2.9 km/s) |

| Propellant | N2O4 / CH6N2[10] |

| Configuration | |

Cross-sectional views of the Crew Dragon 1: Parachutes, 2: Crew access hatch, 3: Draco thrusters, 4: SuperDraco engines, 5: Propellant tank, 6: IDSS port, 7: Port hatch, 8: Control panel, 9: Cargo pallet, 10: Environmental control system, 11: Heat shield | |

Crew Dragon's primary role is to transport crews to and from the ISS under NASA's Commercial Crew Program, a task handled by the Space Shuttle until it was retired in 2011. It will be joined by Boeing's Starliner in this role when NASA certifies it. Crew Dragon is also used for commercial flights to ISS and other destinations, and is expected to be used to transport people to and from Axiom Space's planned space station.

Cargo Dragon brings cargo to the ISS under a Commercial Resupply Services-2 contract with NASA, a duty it shares with Northrop Grumman's Cygnus spacecraft. As of December 2024, it is the only reusable orbital cargo spacecraft in operation, though it may eventually be joined by the under-development Sierra Space Dream Chaser spaceplane.[11]

Development and variants

editThere are two variants of Dragon 2: Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon.[6] Crew Dragon was initially called "DragonRider"[12][13] and it was intended from the beginning to support a crew of seven or a combination of crew and cargo.[14][15] Earlier spacecraft had a berthing port and were berthed to ISS by ISS personnel. Dragon 2 instead has an IDSS-compatible docking port to dock to the International Docking Adapter ports on ISS. It is able to perform fully autonomous rendezvous and docking with manual override ability.[16][17] For typical missions, Crew Dragon remains docked to the ISS for a nominal period of 180 days, but is designed to remain on the station for up to 210 days, matching the Russian Soyuz spacecraft.[18][19][20][21][22][23]

Crew Dragon

editCrew Dragon is capable of autonomous operation. SpaceX and NASA state that it is capable of carrying seven astronauts, but in normal operations it carries two to four crew members and as of December 2024[update] has never carried more than four.[24]

Crew Dragon includes an integrated pusher launch escape system whose eight SuperDraco engines can separate the capsule away from the launch vehicle in an emergency. SpaceX originally intended to use the SuperDraco engines to land Crew Dragon on land; parachutes and an ocean splashdown were envisioned for use only in the case of an aborted launch. Precision water landing under parachutes was proposed to NASA as "the baseline return and recovery approach for the first few flights" of Crew Dragon.[25] However, propulsive landing was later cancelled, leaving ocean splashdown under parachutes as the only option.[26]

In 2012, SpaceX was in talks with Orbital Outfitters about developing space suits to wear during launch and re-entry.[27] Each crew member wears a custom-fitted space suit that provides cooling inside inside the Dragon (IVA type suit) but can also protect its wearer in a rapid cabin depressurization.[28][29] For the Demo-1 mission, a test dummy was fitted with the spacesuit and sensors. The spacesuit is made from Nomex, a fire-retardant fabric similar to Kevlar.

The spacecraft's design was unveiled on 29 May 2014, during a press event at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California.[30][31][32] In October 2014, NASA selected the Dragon spacecraft as one of the candidates to fly American astronauts to the International Space Station, under the Commercial Crew Program.[33][34][35] In March 2022, SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell told Reuters that "We are finishing our final (capsule), but we still are manufacturing components, because we'll be refurbishing".[36] SpaceX later decided to build a fifth Crew Dragon capsule, to be available by 2024.[37] SpaceX also manufactures a new expendable trunk for each flight.

SpaceX's CCtCap contract values each seat on a Crew Dragon flight to be around US$88 million,[38] while the face value of each seat has been estimated by NASA's Office of Inspector General (OIG) to be around US$55 million.[39][40][41] This contrasts with the 2014 Soyuz launch price of US$76 million per seat for NASA astronauts.[42]

Cargo Dragon

editDragon 2 was intended from the earliest design concept to carry crew, or with fewer seats, both crew and cargo.

The cargo version, dubbed Cargo Dragon, became a reality after 2014, when NASA sought bids on a second round of multi-year contracts to bring cargo to the ISS in 2020 through 2024. In January 2016, SpaceX won contracts for six of these flights, dubbed CRS-2.[43] As of April 2024[update], Cargo Dragon has completed nine missions to and from the ISS with six more planned.

Cargo Dragons lack several features of the crewed variant, including seats, cockpit controls, astronaut life support systems, and SuperDraco abort engines.[44][45] Cargo Dragon improves on many aspects of the original Dragon design, including the recovery and refurbishment process.[46]

Since 2021, Cargo Dragon has been able to provide power to some payloads, saving space in the ISS and eliminating the time needed to move the payloads and set them up inside. This feature, announced on 29 August 2021 during the CRS-23 launch, is called Extend-the-Lab. "For CRS-23 there are 3 Extend-the-Lab payloads launching with the mission, and once docked, a 4th which is currently already on the space station will be added to Dragon".[47][48] For the first time, Dragon Cargo Dragon C208 performed test reboost of the ISS via its aft-facing Draco thrusters on 8 November 2024 at 17:50 UTC.[49]

The US Deorbit Vehicle is a planned Cargo Dragon variant that will be used to deorbit the ISS and direct any remnants into the "spacecraft cemetery", a remote area of the southern Pacific Ocean.[50] The vehicle will attach to the ISS using one of the Cargo Dragon vehicles, which will be paired with a longer trunk module equipped with 46 Draco thrusters (instead of the normal 16) and will carry 30,000 kg (66,000 lb) of propellant, nearly six times the normal load. NASA plans to launch the deorbit vehicle in 2030 where it will remain attached, dormant, for about a year as the station's orbit naturally decays to 220 km (140 mi). The spacecraft is to then conduct one or more orientation burns to lower the perigee to 150 km (93 mi), followed by a final deorbiting burn.[51] In June 2024, NASA awarded a contract worth up to $843 million to SpaceX to build the deorbit vehicle as it works to secure funding.[52][53]

Design

editSpaceX, which aims to dramatically lower space transportation costs, designed Dragon 2 to be reused, not discarded as is typical of spacecraft. It is composed of a reusable capsule and a disposable trunk.

SpaceX and NASA initially certified the capsule to be used for five missions. As of March 2024[update], they are working to certify it for up to fifteen missions.[54]

To maximize cost-effectiveness, SpaceX incorporated several innovative design choices. The Crew Dragon employs eight side-mounted SuperDraco engines for its emergency escape system, eliminating the need for a traditional, disposable escape tower. Furthermore, instead of housing the critical and expensive life support, thruster, and propellant storage systems in a disposable service module, Dragon 2 integrates them within the capsule for reuse.

The trunk serves as an adapter between the capsule and the Falcon 9 rocket's second stage and also includes solar panels, a heat-dissipation radiator, and fins to provide aerodynamic stability during emergency aborts.[25] Dragon 2 integrates solar arrays directly into the trunk's structure, replacing the deployable panels of its predecessor, Dragon 1. The trunk can also accommodate unpressurized cargo, such as the Roll Out Solar Array transported to the ISS. The trunk is connected to the capsule using a fitting known as "the claw."[55]

The typical Crew Dragon mission includes four astronauts: a commander who leads the mission and has primary responsibility for operating the spacecraft, a pilot who serves as backup for both command and operations and two mission specialists who may have specific duties assigned depending on the mission. However, the Crew Dragon can fly missions with just two astronauts as needed, and in an emergency, up to seven astronauts could return to Earth from the ISS on Dragon.[7]

On the ground, crews enter the capsule through a side hatch.

On the Crew Dragon, above the two center seats (occupied by the commander and pilot), there is a three-screen control panel. Below the seats is the cargo pallet, where around 230 kilograms (500 lb) of items can be stowed.[56] The capsule’s ceiling includes a small space toilet (with privacy curtain),[57] and an International Docking System Standard (IDSS) port. For private spaceflight missions not requiring ISS docking, the IDSS port can be replaced with a 1.2-meter (3 ft 11 in) domed plexiglass window offering panoramic views, similar to the ISS Cupola.[58] Additionally, SpaceX has developed a "Skywalker" hatch for missions involving extravehicular activities.[59]

The Cargo Dragon is also loaded from the side hatch and has an IDSS port on the ceiling. However, it lacks the control panels, windows, and seats of the Crew Dragon.

The spacecraft can be operated in full vacuum, and "the crew will wear SpaceX-designed space suits to protect them from a rapid cabin depressurization emergency event". The spacecraft has also been designed to be able to land safely with a leak "of up to an equivalent orifice of 6.35 mm [0.25 in] in diameter".[25]

The spacecraft's nose cone protects the docking port and four forward-facing thrusters during ascent and reentry. This component pivots open for in-space operations.[25][32] Dragon 2's propellant and helium pressurant for emergency abort and orbital maneuvers are stored in composite-carbon-overwrap titanium spherical tanks at the capsule's base in an area known as the service section.

For launch aborts, the capsule relies on eight SuperDraco engines arranged in four redundant pairs. Each engine generates 71 kN (16,000 lbf) of thrust.[30] Sixteen smaller Draco thrusters placed around the spacecraft control its attitude and perform orbital maneuvers.

When the capsule returns to Earth, a PICA-3 heat shield safeguards the capsule during reentry. Dragon 2 uses a total of six parachutes (two drogues and four mains) to decelerate after atmospheric entry and before splashdown, compared to the five used by Dragon 1.[60] The additional parachute was required by NASA as a safety measure after a Dragon 1 suffered a parachute malfunction. The company also went through two rounds of parachute development before being certified to fly with crew.[61] In 2024, the use of the SuperDraco thrusters for propulsive landing was enabled again, but only as a back-up for parachute emergencies.[62]

Crewed flights

editCrew Dragon is used by both commercial and government customers. Axiom launches commercial astronauts to the ISS and intends to eventually launch to their own private space station. NASA flights to the ISS have four astronauts, with the added payload mass and volume used to carry pressurized cargo.[60]

On 16 September 2014, NASA announced that SpaceX and Boeing had been selected to provide crew transportation to the ISS. SpaceX was to receive up to US$2.6 billion under this contract to provide development test flights and up to six operational flights.[63] Dragon was the less expensive proposal,[34] but NASA's William H. Gerstenmaier considered the Boeing Starliner proposal the stronger of the two. However, Crew Dragon's first operational flight, SpaceX Crew-1, was on 16 November 2020 after several test flights, while Starliner suffered multiple problems and delays, with its first operational flight slipping to no earlier than early 2025.[64]

In a departure from the prior NASA practice, where construction contracts with commercial firms led to direct NASA operation of the spacecraft, NASA is purchasing space transport services from SpaceX, including construction, launch, and operation of the Dragon 2.[65]

NASA approved a new propellant loading procedure due to the Falcon 9 rocket's novel use of superchilled propellants. Unlike earlier NASA spacecraft, such as the Saturn V and Space Shuttle—where propellants were fully loaded hours before launch and before astronauts boarded—on the Falcon 9, propellants are loaded just before launch to keep the liquid oxygen near −340 °F (−206.7 °C) and the kerosene near 20 °F (−7 °C).[66] Propellant loading begins approximately 40 minutes before liftoff, with the launch escape system active to ensure the crew can be safely pulled away from the rocket in the event of an emergency during fuel loading.[67]

The first uncrewed test mission, Demo-1, launched to the International Space Station (ISS) on 2 March 2019.[68] After schedule slips,[69] the first crewed flight, Demo-2, launched on 30 May 2020.[70]

Testing

editSpaceX planned a series of four flight tests for the Crew Dragon: a pad abort test, an uncrewed orbital flight to the ISS, an in-flight abort test, and finally, a crewed flight to the ISS,[71] which was initially planned for July 2019,[69] but after a Dragon capsule explosion, was delayed to May 2020.[72]

Pad abort test

editThe pad abort test was conducted successfully on 6 May 2015 at SpaceX's leased SLC-40 launch site.[60] Dragon landed safely in the ocean to the east of the launchpad 99 seconds after ignition of the SuperDraco engines.[73] While a flight-like Dragon 2 and trunk were used for the pad abort test, they rested atop a truss structure for the test rather than a full Falcon 9 rocket. A crash test dummy embedded with a suite of sensors was placed inside the test vehicle to record acceleration loads and forces at the crew seat, while the remaining six seats were loaded with weights to simulate full-passenger-load weight.[65][74] The test objective was to demonstrate sufficient total impulse, thrust and controllability to conduct a safe pad abort. A fuel mixture ratio issue was detected after the flight in one of the eight SuperDraco engines causing it to under perform, but did not materially affect the flight.[75][76][77]

On 24 November 2015, SpaceX conducted a test of Dragon 2's hovering abilities at the firm's rocket development facility in McGregor, Texas. In a video, the spacecraft is shown suspended by a hoisting cable and igniting its SuperDraco engines to hover for about 5 seconds, balancing on its 8 engines firing at reduced thrust to compensate exactly for gravity.[78] The test vehicle was the same capsule that performed the pad abort test earlier in 2015; it was nicknamed DragonFly.[79]

Demo-1: orbital flight test

editIn 2015, NASA named its first Commercial Crew astronaut cadre of four veteran astronauts to work with SpaceX and Boeing – Robert Behnken, Eric Boe, Sunita Williams, and Douglas Hurley.[80] The Demo-1 mission completed the last milestone of the Commercial Crew Development program, paving the way to starting commercial services under an upcoming ISS Crew Transportation Services contract.[65][81] On 3 August 2018, NASA announced the crew for the DM-2 mission.[82] The crew of two consisted of NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. Behnken previously flew as mission specialist on the STS-123 and the STS-130 missions. Hurley previously flew as a pilot on the STS-127 mission and on the final Space Shuttle mission, STS-135.[83]

The first orbital test of Crew Dragon was an uncrewed mission, commonly called "Demo-1" and launched on 2 March 2019.[84][85] The spacecraft tested the approach and automated docking procedures with the ISS,[86] remained docked until 8 March 2019, then conducted the full re-entry, splashdown and recovery steps to qualify for a crewed mission.[87][88] Life-support systems were monitored for the entirety the test flight. The same capsule was planned to be re-used in June 2019 for an in-flight abort test before it exploded on 20 April 2019.[84][89]

Explosion during testing

editOn 20 April 2019, Crew Dragon C204, the capsule used in the Demo-1 mission, was destroyed in an explosion during static fire testing at the Landing Zone 1 facility.[90][91] On the day of the explosion, the initial testing of the Crew Dragon's Draco thrusters was successful, with the anomaly occurring during the test of the SuperDraco abort system.[92]

Telemetry, high-speed camera footage, and analysis of recovered debris indicate the problem occurred when a small amount of dinitrogen tetroxide leaked into a helium line used to pressurize the propellant tanks. The leakage apparently occurred during pre-test processing. As a result, the pressurization of the system 100 ms before firing damaged a check valve and resulted in the explosion.[92][93]

SpaceX modified the Dragon 2 replacing check valves with burst discs, which are designed for single use, and the adding of flaps to each SuperDraco to seal the thrusters prior to splashdown, preventing water intrusion.[94] The SuperDraco engine test was repeated on 13 November 2019 with Crew Dragon C205. The test was successful, showing that the modifications made to the vehicle were successful.[95]

Since the destroyed capsule had been slated for use in the upcoming in-flight abort test, the explosion and investigation delayed that test and the subsequent crewed orbital test.[96]

In-flight abort test

editThe Crew Dragon in-flight abort test was launched on 19 January 2020 at 15:30 UTC from LC-39A on a suborbital trajectory to conduct a separation and abort scenario in the troposphere at transonic velocities shortly after passing through max Q, where the vehicle experiences maximum aerodynamic pressure. The Dragon 2 used its SuperDraco abort engines to push itself away from the Falcon 9 after an intentional premature engine cutoff, after which the Falcon was destroyed by aerodynamic forces. The Dragon followed its suborbital trajectory to apogee, at which point the spacecraft's trunk was jettisoned. The smaller Draco engines were then used to orient the vehicle for the descent. All major functions were executed, including separation, engine firings, parachute deployment, and landing.

Dragon 2 splashed down at 15:38:54 UTC just off the Florida coast in the Atlantic Ocean.[97] The test objective was to demonstrate the ability to safely move away from the ascending rocket under the most challenging atmospheric conditions of the flight trajectory, imposing the worst structural stress of a real flight on the rocket and spacecraft.[60] The abort test was performed using a Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket with a fully fueled second stage with a mass simulator replacing the Merlin engine.[98]

Earlier, this test had been scheduled before the uncrewed orbital test,[99] however, SpaceX and NASA considered it safer to use a flight representative capsule rather than the test article from the pad abort test.[100]

This test was previously planned to use the capsule C204 from Demo-1, however, C204 was destroyed in an explosion during a static fire testing on 20 April 2019.[101] Capsule C205, originally planned for Demo-2 was used for the In-Flight Abort Test[102] with C206 being planned for use during Demo-2. This was the final flight test of the spacecraft before it began carrying astronauts to the International Space Station under NASA's Commercial Crew Program.

Prior to the flight test, teams completed launch day procedures for the first crewed flight test, from suit-up to launch pad operations. The joint teams conducted full data reviews that needed to be completed prior to NASA astronauts flying on the system during SpaceX's Demo-2 mission.[103]

Demo-2: crewed orbital flight test

editOn 17 April 2020, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced the first crewed Crew Dragon Demo-2 to the International Space Station would launch on 27 May 2020.[104] Astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley crewed the mission, marking the first crewed launch to the International Space Station from U.S. soil since STS-135 in July 2011. The original launch was postponed to 30 May 2020 due to weather conditions at the launch site.[105] The second launch attempt was successful, with capsule C206, later named Endeavour by the crew, launching on 30 May 2020 19:22 UTC.[106][107] The capsule successfully docked with the International Space Station on 31 May 2020 at 14:27 UTC.[108][109][110] On 2 August 2020, Crew Dragon undocked and splashed-down successfully in the Atlantic Ocean. Launching in the Dragon 2 spacecraft was described by astronaut Bob Behnken as "smooth off the pad" but "we were definitely driving and riding a dragon all the way up ... a little bit less g's [than the Space Shuttle] but more 'alive' is probably the best way I would describe it".[111]

Regarding descent in the spacecraft, Behnken stated, "Once we descended a little bit into the atmosphere, Dragon really came alive. It started to fire thrusters and keep us pointed in the appropriate direction. The atmosphere starts to make noise—you can hear that rumble outside the vehicle. And as the vehicle tries to control, you feel a little bit of that shimmy in your body. ... We could feel those small rolls and pitches and yaws—all those little motions were things we picked up on inside the vehicle. ... All the separation events, from the trunk separation through the parachute firings, were very much like getting hit in the back of the chair with a baseball bat ... pretty light for the trunk separation but with the parachutes it was a pretty significant jolt".[112]

List of vehicles

edit| S/N | Name | Type | Status | Flights | Flight time | Total flight time | Notes | Cat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C201 | DragonFly | Prototype | Retired | 1 | 99s (Pad Abort Test) | 99s | Prototype used for pad abort test at Cape Canaveral and tethered hover tests at the McGregor Test Facility. | |

| C202 | None | Prototype | Retired | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pressure vessel qualification module used for structural testing. | |

| C203 | None | Prototype | In use | N/A | N/A | N/A | Environmental control and life support system testing module, still in use for human-in-the-loop testing. | |

| C204 | None | Crew | Destroyed | 1 | 6d 5h 56m (Demo-1) | 6d 5h 56m | First Dragon 2 to fly in space. Only flight was Demo-1; accidentally destroyed during ground testing of the abort thrusters weeks after the flight. | |

| C205 | None | Crew | Retired | 1 | 8m 54s (In-Flight Abort Test) | 8m 54s | Was originally to be used on Demo-2 but instead flew the Crew Dragon In-Flight Abort Test due to the destruction of C204 and was retired afterwards. | |

| C206 | Endeavour | Crew | Active | 5 | 701d 21h 16m | First vehicle to carry crew; named after Space Shuttle Endeavour. First flown during Crew Demo-2.[116] Has since flown Crew-2,[117] Axiom-1, and Crew-6. | ||

| C207 | Resilience | Crew | Active | 3 |

|

175d 3h 4m | First flew on Crew-1 on 16 November 2020.[118] Used for Inspiration4, featuring the largest window ever flown in space in place of the docking adapter.[119] It also flew on the Polaris Dawn mission, which involved the first private EVA. Scheduled to fly Fram2. | |

| C208 | None | Cargo | Active | 5 | 175d 13h 52m | First Cargo Dragon 2, which flew the CRS-21, CRS-23, CRS-25, CRS-28 and CRS-31 missions.[120] | ||

| C209 | None | Cargo | Active | 4 | 142d 2h 7m | Second Cargo Dragon 2, which flew the CRS-22, CRS-24, CRS-27 and CRS-30 missions. | ||

| C210 | Endurance | Crew | Active | 3 | 532d 15h | First flew on Crew-3 on 11 November 2021.[121] Has since flown Crew-5 and Crew-7. | ||

| C211 | None | Cargo | Active | 2 | 88d 7h 4m | Third Cargo Dragon 2, which flew the CRS-26 and CRS-29 missions.[122][123] | ||

| C212 | Freedom | Crew | Active (docked to ISS) |

4 | 302 days, 11 hours, 17 minutes (currently in space) |

First flew on Crew-4 on 24 April 2022.[122] Has since flown Axiom-2, Axiom-3, and Crew-9. | ||

| C213 | TBA | Crew | Active | None | None | None | Scheduled to make maiden flight on Crew-10.[124] |

List of flights

editList includes only completed or currently manifested missions. Dates are listed in UTC, and for future events, they are the earliest possible opportunities (also known as NET dates) and may change.

Crew Dragon flights

edit| Mission and Patch | Capsule[115] | Launch date | Landing date | Remarks | Crew | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pad Abort Test (patch) | C201 DragonFly | 6 May 2015 | Simulating an escape from a rocket failure on the ground, Crew Dragon's SuperDraco engines lifted the capsule from a ground pad at SLC-40 and propelled it to a safe splashdown in the nearby ocean. | — | Success | |

| Demo-1 (patch) | C204 | 2 March 2019 | 8 March 2019 | Uncrewed orbital test flight, successfully docked with the ISS. | — | Success |

| In-Flight Abort Test (patch) | C205 | 19 January 2020 | Booster was commanded to simulate an in-flight engine failure. In response, Crew Dragon's SuperDraco engines fired successfully, propelling the capsule away to a safe splashdown. | — | Success | |

| Demo-2 | C206.1 Endeavour | 30 May 2020 | 2 August 2020 | First crewed flight test of Dragon 2. The mission was extended from two weeks to nine, to allow the crew to bolster activity on the ISS ahead of Crew-1. | Success | |

| Crew-1 | C207.1 Resilience | 16 November 2020 | 2 May 2021 | First operational Commercial Crew flight, flying four astronauts to the ISS for a six-month mission. Broke the record for the longest spaceflight by a U.S. crew vehicle, previously held by the Skylab 4 mission.[125] | Success | |

| Crew-2 | C206.2 Endeavour | 23 April 2021 | 9 November 2021 | First reuse of a capsule and booster rocket. Crew includes the first ESA astronaut to fly on Crew Dragon. After spending almost 200 days in orbit, the Crew Dragon Endeavour set the record for the longest spaceflight by a U.S. crew vehicle previously set by her sibling Crew Dragon Resilience on May 2, 2021.[126] | Success | |

| Inspiration4 (patch 1 and 2) | C207.2 Resilience | 16 September 2021 | 18 September 2021 | The first fully private, all-civilian orbital flight. Crew reached a 585 km (364 mi) orbit and conducted science experiments and public outreach activities for three days.[129] First standalone orbital Crew Dragon flight and the first flight with the cupola. | Success | |

| Crew-3 | C210.1 Endurance | 11 November 2021 | 6 May 2022 | Success | ||

| Axiom-1 (patch) | C206.3 Endeavour | 8 April 2022 | 25 April 2022 | First fully private flight to the ISS. Contracted by Axiom Space. Axiom employee served as commander with three paying tourists. | Success | |

| Crew-4 | C212.1 Freedom | 27 April 2022 | 14 October 2022 | Success | ||

| Crew-5 | C210.2 Endurance | 5 October 2022 | 12 March 2023 | First crew to include a Russian cosmonaut as part of Dragon–Soyuz swap flights to ensure that all countries are familiar with their separate systems if either vehicle is grounded for an extended period.[130] | Success | |

| Crew-6 | C206.4 Endeavour | 2 March 2023 | 4 September 2023 | Success | ||

| Axiom-2 (patch) | C212.2 Freedom | 21 May 2023 | 31 May 2023 | Fully private flight to the ISS. Contracted by Axiom Space. Axiom employee served as commander, Saudi Space Agency bought two seats and sent two astronauts to research cancer, cloud seeding, and microgravity.[131] Third seat purchased by a tourist. | Success | |

| Crew-7 | C210.3 Endurance | 26 August 2023 | 12 March 2024 | Success | ||

| Axiom-3 (patch) | C212.3 Freedom | 18 January 2024[132] | 9 February 2024 | Fully private flight to the ISS. Axiom employee served as commander, other seats purchased by AM, TUA and SNSA/ESA. | Success | |

| Crew-8 | C206.5 Endeavour | 4 March 2024 | 25 October 2024 | Longest Crew Dragon mission. ISS stay extended and two makeshift seats added to allow Crew-8 to serve as "lifeboat" for the Boeing CFT crew if needed. | Success | |

| Polaris Dawn (patch) | C207.3 Resilience | 10 September 2024 | 15 September 2024 | Fully private orbital flight, including two SpaceX employees. First of three planned flights of the private Polaris Program. Flew 1,400 km (870 mi) away from Earth, the highest orbit of the planet flown by a crewed spacecraft to date. Isaacman and Gillis made the first commercial spacewalk during the mission.[133] | Success | |

| Crew-9 | C212.4 Freedom | 28 September 2024 | March 2025 | Was the first crewed mission to launch from SLC-40.[134] Launched with only two crew members and will return with the crew of the Boeing Crew Flight Test due to issues with the Boeing Starliner Calypso.[135] |

|

In progress |

| Fram2 (patch) | C207.4 Resilience | March 2025 | March 2025 | Fully private, all-civilian orbital flight. Planned to be the first crewed mission to launch into a polar orbit.[136] | Planned | |

| Crew-10 | C213.1[124] | March 2025[137] | July 2025 | Planned | ||

| Axiom-4 | TBA | Q2 2025[139] | Q2 2025 | Fully private flight to the ISS. Axiom employee will serve as commander; other seats purchased by ISRO, POLSA/ESA and Hungary. | Planned | |

| Crew-11 | TBA | July 2025[140] | TBA | TBA | Planned | |

| Vast-1 | TBA | August 2025 | TBA | Servicing of the Haven-1 space station.[141] | TBA | Planned |

| Axiom-5 | TBA | 2025 | 2025 | Fully private flight to the ISS.[142] | TBA | Planned |

| Polaris-2 | TBA | TBA | TBA | Last Polaris Program flight to use Crew Dragon (final flight plans to use Starship).[143] On hiatus since Jared Isaacman is nominated as NASA Administrator. |

|

Planned |

| Crew-12[144] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | Planned | |

| Crew-13[144] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | Planned | |

| Crew-14[144] | TBA | TBA | TBA | TBA | Planned | |

Cargo Dragon flights

edit| Mission and Patch | Capsule[145] | Launch date | Landing date | Remarks | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRS-21 | C208.1 | 6 December 2020 | 14 January 2021 | First SpaceX mission performed under the CRS-2 contract with NASA and the first flight of Cargo Dragon 2. Also delivered the Nanoracks Bishop Airlock module. | Success |

| CRS-22 | C209.1 | 3 June 2021 | 10 July 2021 | Also delivered solar arrays iROSA 1 and iROSA 2 | Success |

| CRS-23 | C208.2 | 29 August 2021 | 1 October 2021 | Success | |

| CRS-24 | C209.2 | 21 December 2021 | 24 January 2022 | Success | |

| CRS-25 | C208.3 | 15 July 2022 | 20 August 2022 | Success | |

| CRS-26 | C211.1 | 26 November 2022 | 11 January 2023 | Also delivered solar arrays iROSA 3 and iROSA 4.[146] | Success |

| CRS-27 | C209.3 | 15 March 2023 | 15 April 2023 | Success | |

| CRS-28 | C208.4 | 5 June 2023, 15:47 | 30 June 2023 | Also delivered solar arrays iROSA 5 and iROSA 6.[147] With this mission, Dragon 2 fleet's 1,324 days in orbit surpassed the Space Shuttle. This was the 38th Dragon mission to ISS, surpassing the Shuttle's 37.[148] | Success |

| CRS-29 | C211.2 | 10 November 2023 | 22 December 2023 | Success | |

| CRS-30 | C209.4 | 21 March 2024 | 30 April 2024 | First Dragon 2 launch from SLC-40. | Success |

| CRS-31 | C208.5 | 5 November 2024 | 16 December 2024 | First Dragon to perform a reboost of the ISS.[149] | Success |

| CRS-32 | TBA | March 2025[150][151] | Planned | ||

| CRS-33 | TBA | 2025[150][152] | Planned | ||

| CRS-34 | TBA | 2025[150][153] | Planned | ||

| CRS-35 | TBA | 2025[150][154] | Planned | ||

| United States Deorbit Vehicle | TBA | 2030[155] | To deorbit the ISS after it is decommissioned. | Planned |

Timeline

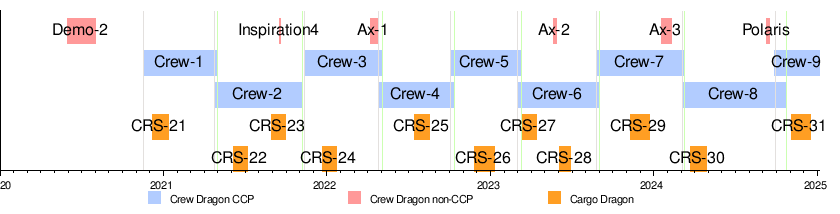

editCrew Dragon has flown nine operational CCP missions and seven other missions. Cargo Dragon has flown eleven missions. For brevity, the Demo-1 mission is not shown.

See also

edit- Comparison of crewed space vehicles

- Comparison of space station cargo vehicles

- List of crewed spacecraft

- Crew Dragon Launch Abort System

- Private spaceflight – Spaceflight technology development not paid for by a government agency

Notes

edit- ^ The reentry capsule weighs 9,600 kg (21,200 lb) including crew + 150 kg (330 lb) payload (Crew Dragon Demo-2)

- ^ up to 2,507 kg (5,527 lb) pressurized and up to 800 kg (1,800 lb) unpressurized

- ^ McArthur used the same seat of the Crew Dragon Endeavour in this mission which her husband, Bob Behnken, used in the earlier SpaceX Demo-2 mission.[127]

- ^ The European Portion of SpaceX Crew-2 is called Mission Alpha, which is headed by Thomas Pesquet.[128]

- ^ The European Portion of SpaceX Crew-3 is called Mission Cosmic Kiss, which is headed by Matthias Maurer shown by the logo

- ^ a b c d Axiom Space employee

- ^ a b SpaceX employee

References

edit- ^ "DragonLab datasheet" (PDF). Hawthorne, California: SpaceX. 8 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2011.

- ^ "NASA, SpaceX to Launch First Astronauts to Space Station from U.S. Since 2011". NASA. Retrieved 20 June 2024. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Heiney, Anna (23 July 2020). "Top 10 Things to Know for NASA's SpaceX Demo-2 Return". nasa.gov. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

At the time of undock, Dragon Endeavour and its trunk weigh approximately 27,600 pounds

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ a b "Final Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact for Issuing SpaceX a Launch License for an In-Flight Dragon Abort Test" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. June 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e SpaceX (1 March 2019). "Dragon". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Audit of Commercial Resupply Services to the International Space Station Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine NASA 26 April 2018 Report No. IG-18-016 Quote: "For SpaceX, certification of the company's unproven cargo version of its Dragon 2 spacecraft for CRS-2 missions carries risk while the company works to resolve ongoing concerns related to software traceability and systems engineering processes" This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Howell, Elizabeth (9 August 2024). "Will SpaceX carry Boeing Starliner crew home? Here's how Dragon could do it". Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Rauf, Jim (Fall 2023). "SpaceX Dragon Spacecraft" (PDF). University of Cincinnati.

- ^ a b Richardson, Derek. "Dragon 2". Orbital Velocity. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ "The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2012" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. February 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Dream Chaser Lifting Body Set For Delivery To NASA Ahead Of 2024 Launch | Aviation Week Network". aviationweek.com. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Final Environmental Assessment for Issuing an Experimental Permit to SpaceX for Operation of the DragonFly Vehicle at the McGregor Test Site, McGregor, Texas" (PDF). FAA. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Gwynne Shotwell (21 March 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell. The Space Show. Event occurs at 24:05–24:45 and 28:15–28:35. 2212. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

we call it v2 for Dragon. That is the primary vehicle for crew, and we will retrofit it back to cargo

- ^ "Q+A: SpaceX Engineer Garrett Reisman on Building the World's Safest Spacecraft". PopSci. 13 April 2012. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

DragonRider, SpaceX's crew-capable variant of its Dragon capsule

- ^ "SpaceX Completes Key Milestone to Fly Astronauts to International Space Station". SpaceX. 20 October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ "Dragon Overview". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Parma, George (20 March 2011). "Overview of the NASA Docking System and the International Docking System Standard" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

iLIDS was later renamed the NASA Docking System (NDS), and will be NASA's implementation of an IDSS compatible docking system for all future U.S. vehicles

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ Bayt, Rob (16 July 2011). "Commercial Crew Program: Key Driving Requirements Walkthrough". NASA. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Oberg, Jim (28 March 2007). "Space station trip will push the envelope". NBC News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Bolden, Charles (9 May 2012). "2012-05-09_NASA_Response" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ With the exception of the Project Gemini spacecraft, which used twin ejection seats: "Encyclopedia Astronautica: Gemini Ejection" Archived 25 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine Astronautix.com Retrieved 24 January 2013

- ^ Chow, Denise (18 April 2011). "Private Spaceship Builders Split Nearly US$270 Million in NASA Funds". Space.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "Spaceship teams seek more funding" MSNBC 10 December 2010 Retrieved 14 December 2010

- ^ "COMMERCIAL CREW PROGRAM" (PDF). NASA. p. 20. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d Reisman, Garrett (27 February 2015). "Statement of Garrett Reisman, Director of Crew Operations, Space Explorations Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) before the Subcommittee on Space, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives" (PDF). United States House of Representatives, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "SpaceX Updates – Taking the next step: Commercial Crew Development Round 2". SpaceX. 17 January 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Sofge, Eric (19 November 2012). "The Deep-Space Suit". PopSci. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Dragon". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Gibbens, Sarah. "A First Look at the Spacesuits of the Future". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ a b Norris, Guy (30 May 2014). "SpaceX Unveils 'Step Change' Dragon 'V2'". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (30 May 2014). "SpaceX Unveils Dragon V2 Spaceship, a Manned Space Taxi for Astronauts — Meet Dragon V2: SpaceX's Manned Space Taxi for Astronaut Trips". Space.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (30 May 2014). "SpaceX lifts the lid on the Dragon V2 crew spacecraft". NASAspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Post, Hannah (16 September 2014). "NASA Selects SpaceX to be Part of America's Human Spaceflight Program". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Why NASA Rejected Sierra Nevada's Commercial Crew Vehicle". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Berger, Eric (9 June 2017). "So SpaceX is having quite a year". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (28 March 2022). "EXCLUSIVE SpaceX ending production of flagship crew capsule". Reuters. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (19 November 2022). "SpaceX to launch last new cargo Dragon spacecraft". SpaceNews. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

Walker revealed at the briefing SpaceX plans to build a fifth and likely final Crew Dragon.

- ^ Potter, Sean (31 August 2022). "NASA Awards SpaceX More Crew Flights to Space Station". NASA.gov. NASA.

This is a firm fixed-price, indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract modification for the Crew-10, Crew-11, Crew-12, Crew-13, and Crew-14 flights. The value of this modification for all five missions and related mission services is $1,436,438,446. The amount includes ground, launch, in-orbit, and return and recovery operations, cargo transportation for each mission, and a lifeboat capability while docked to the International Space Station. The period of performance runs through 2030 and brings the total CCtCap contract value with SpaceX to $4,927,306,350

- ^ McCarthy, Niall (4 June 2020). "Why SpaceX Is A Game Changer For NASA [Infographic]". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

According to the NASA audit, the SpaceX Crew Dragon's per-seat cost works out at an estimated $55 million while a seat on Boeing's Starliner is approximately $90 million ...

- ^ McFall-Johnsen, Morgan; Mosher, Dave; Secon, Holly (26 January 2020). "SpaceX is set to launch astronauts on Wednesday. Here's how Elon Musk's company became NASA's best shot at resurrecting American spaceflight". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

Eventually, a round-trip seat on the Crew Dragon is expected to cost about $US55 million. A seat on Starliner will cost about $US90 million. That's according to a November 2019 report from the NASA Office of Inspector General.

- ^ Wall, Mike (16 November 2019). "Here's How Much NASA Is Paying Per Seat on SpaceX's Crew Dragon & Boeing's Starliner". Space.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

NASA will likely pay about $90 million for each astronaut who flies aboard Boeing's CST-100 Starliner capsule on International Space Station (ISS) missions, the report estimated. The per-seat cost for SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule, meanwhile, will be around $55 million, according to the OIG's calculations.

- ^ "SpaceX scrubs launch to ISS over rocket engine problem". Deccan Chronicle. 19 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Bergin, Chris. "NASA lines up four additional CRS missions for Dragon and Cygnus". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Ralph, Eric. "Dragon 2 modifications to Carry Cargo for CRS-2 missions". SpaceX/Teslarati. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Audit of Commercial Resupply Services to the International Space Center (PDF). Office of Inspector General (Report). Vol. IG-18-016. NASA. 26 April 2018. pp. 24, 28–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (2 August 2019). "SpaceX to begin flights under new cargo resupply contract next year". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ CRS-23 Mission, 29 August 2021, archived from the original on 29 August 2021, retrieved 29 August 2021

- ^ CRS-21 Mission

- ^ Foust, Jeff (5 November 2024). "Falcon 9 launches cargo Dragon mission to ISS". SpaceNews. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "NASA plans to take International Space Station out of orbit in January 2031 by crashing it into 'spacecraft cemetery'". Sky News. 1 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (9 May 2023). "NASA proposes 'hybrid' contract approach for space station deorbit vehicle". SpaceNews. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "NASA Selects International Space Station US Deorbit Vehicle – NASA". Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (1 May 2024). "Nelson lobbies Congress to fund ISS deorbit vehicle in supplemental spending bill". SpaceNews. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Tingley, Brett (6 March 2024). "NASA, SpaceX looking to extend lifespan of Crew Dragon spacecraft to 15 flights". space.com. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Davenport, Justin (14 September 2024). "Polaris Dawn returns home after landmark commercial spaceflight". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Crew-1 Dragon Arrives At the International Space Station". SpaceNews. 16 November 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (11 November 2021). "SpaceX's toilet is working fine, thanks for asking". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (30 March 2021). "SpaceX's Dragon spaceship is getting the ultimate window for private Inspiration4 spaceflight". Space.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (11 July 2024). "Overview: Approaching Dawn". CNBC's Investing in Space Newsletter. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bergin, Chris (28 August 2014). "Dragon V2 will initially rely on parachute landings". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (5 December 2019). "SpaceX's Crew Dragon parachutes are almost ready for NASA astronauts". TESLARATI. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ McCrea, Aaron (10 October 2024). "Dragon receives long-planned propulsive landing upgrade after years of development". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "NASA Chooses American Companies to Transport U.S. Astronauts to International Space Station". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 March 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2014. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Scott, Heather (12 October 2023). "NASA Updates Commercial Crew Planning Manifest". NASA. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Bergin, Chris (5 March 2015). "Commercial crew demo missions manifested for Dragon 2 and CST-100". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (17 December 2015). "-340 F in this case. Deep cryo increases density and amplifies rocket performance. First time anyone has gone this low for O2. [RP-1 chilled] from 70F to 20 F" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015 – via Twitter.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (17 August 2018). "NASA, SpaceX Agree on Plans for Crew Launch Day Operations". NASA. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA's Commercial Crew Program Target Test Flight Dates". NASA. 21 November 2018. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NASA, Partners Update Commercial Crew Launch Dates". NASA Commercial Crew Program Blog. 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Chan, Athena (17 April 2020). "Elon Musk Shares Simulation Video, Schedule Of Crew Dragon's First Crewed Flight". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Ray, Justin (13 December 2016). "S.S. John Glenn freighter departs space station after successful cargo delivery". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "NASA sets tentative date for launching astronauts in SpaceX ship". futurism.com. 26 June 2019. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (6 May 2015). "SpaceX crew capsule completes dramatic abort test". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (3 April 2015). "SpaceX preparing for a busy season of missions and test milestones". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ "SpaceX Crew Dragon pad abort: Test flight demos launch escape system". collectspace.com. 6 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (6 May 2015). "Dragon 2 conducts Pad Abort leap in key SpaceX test". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "SpaceX crew capsule completes dramatic abort test". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Dragon 2 Propulsive Hover Test. SpaceX. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (21 October 2015). "SpaceX DragonFly arrives at McGregor for testing". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "NASA assigns 4 astronauts to commercial Boeing, SpaceX test flights". collectspace.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (27 January 2015). "Private Space Taxis on Track to Fly in 2017". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "NASA Assigns Crews to First Test Flights, Missions on Commercial Spacecraft". NASA. 3 August 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2018. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Nail, Rachael (16 July 2021). "Commander of first crewed SpaceX launch Doug Hurley retires". Florida Today. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ a b "NASA, Partners Update Commercial Crew Launch Dates". NASA Commercial Crew Program Blog. 6 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Crew Demo-1 | Launch". YouTube. 2 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "SpaceX Crew Dragon Hatch Open". NASA. 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Crew Demo 1 Mission Overview" (PDF). SpaceX. March 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ SpaceX #CrewDragon Demonstration Flight Return to Earth. YouTube. 8 March 2019.

- ^ Baylor, Michael (20 April 2019). "SpaceX's Crew Dragon spacecraft suffers an anomaly during static fire testing at Cape Canaveral". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Bridenstine, Jim [@JimBridenstine] (20 April 2019). "NASA has been notified about the results of the @SpaceX Static Fire Test and the anomaly that occurred during the final test. We will work closely to ensure we safely move forward with our Commercial Crew Program" (Tweet). Retrieved 21 April 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ Mosher, Dave. "SpaceX confirmed that its Crew Dragon spaceship for NASA was 'destroyed' by a recent test. Here's what we learned about the explosive failure". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ a b Shanklin, Emily (15 July 2019). "Update: In-Flight Abort Static Fire Test Anomaly Investigation". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ William, Harwood (15 July 2020). "Explosion that destroyed SpaceX Crew Dragon is blamed on leaking valve". CBS News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (14 November 2019). "SpaceX fires up redesigned Crew Dragon as NASA reveals SuperDraco thruster 'flaps'". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (13 November 2019). "SpaceX fires up Crew Dragon thrusters in key test after April explosion". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Eric M. (18 June 2019). "NASA boss says no doubt SpaceX explosion delays flight program". Journal Pioneer. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Northon, Karen (19 January 2020). "NASA, SpaceX Complete Final Major Flight Test of Crew Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Richardson, Derek (30 July 2016). "Second SpaceX Crew Flight Ordered by NASA". Spaceflight Insider. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

Currently, the first uncrewed test of the spacecraft is expected to launch in May 2017. Sometime after that, SpaceX plans to conduct an in-flight abort to test the SuperDraco thrusters while the rocket is traveling through the area of maximum dynamic pressure – Max Q.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (4 February 2016). "SpaceX seeks to accelerate Falcon 9 production and launch rates this year". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

Shotwell said the company is planning an in-flight abort test of the Crew Dragon spacecraft before the end of this year, where the vehicle uses its thrusters to separate from a Falcon 9 rocket during ascent. That will be followed in 2017 by two demonstration flights to the International Space Station, the first without a crew and the second with astronauts on board, and then the first operational mission.

- ^ Siceloff, Steven (1 July 2015). "More Fidelity for SpaceX In-Flight Abort Reduces Risk". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

In the updated plan, SpaceX would launch its uncrewed flight test (DM-1), refurbish the flight test vehicle, then conduct the in-flight abort test prior to the crew flight test. Using the same vehicle for the in-flight abort test will improve the realism of the ascent abort test and reduce risk.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ Shanklin, Emily (15 July 2019). "Update: In-Flight Abort Static Fire Test Anomaly Investigation". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "SpaceX conducts successful Crew Dragon In-Flight Abort Test". NASA Spaceflight. 17 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Northon, Karen (19 January 2020). "NASA, SpaceX Complete Final Major Flight Test of Crew Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Bridenstine, Jim [@JimBridenstine] (17 April 2020). "BREAKING: On May 27, @NASA will once again launch American astronauts on American rockets from American soil! With our @SpaceX partners, @Astro_Doug and @AstroBehnken will launch to the @Space_Station on the #CrewDragon spacecraft atop a Falcon 9 rocket. Let's #LaunchAmerica pic.twitter.com/RINb3mfRWI" (Tweet). Retrieved 17 April 2020 – via Twitter. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ @SpaceX (27 May 2020). "Standing down from launch today due to unfavorable weather in the flight path. Our next launch opportunity is Saturday, May 30 at 19:22 UTC" (Tweet). Retrieved 27 May 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ @SpaceX (30 May 2020). "Liftoff!" (Tweet). Retrieved 31 May 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ @elonmusk (30 May 2020). "Dragonship Endeavor" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ @SpaceX (31 May 2020). "Docking confirmed – Crew Dragon has arrived at the @space_station!" (Tweet). Retrieved 31 May 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ "SpaceX's historic Demo-2 delivers NASA astronauts to ISS". CNET. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ Bartels, Meghan (last update) (31 May 2020). "SpaceX's 1st Crew Dragon with astronauts docks at space station in historic rendezvous". Space.com. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "We were surprised a little bit at how smooth things were off the pad ... and our expectation was as we continued with the flight into second stage that things would basically get a lot smoother than the Space Shuttle did, but Dragon was huffing and puffing all the way into orbit, and we were definitely driving and riding a dragon all the way up, and so it was not quite the same ride, the smooth ride as the Space Shuttle was up to MECO. A little bit less g's but a little bit more 'alive' is probably the best way I would describe it". NASA Astronauts Arrive at the International Space Station on SpaceX Spacecraft. 31 May 2020. Event occurs at 03:46:02. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (4 August 2020). "SpaceX: Nasa crew describe rumbles and jolts of return to Earth". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (29 May 2019). "NASA briefly updates status of Crew Dragon anomaly, SpaceX test schedule". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ SCR00CHY (21 May 2020). "List of Dragon Capsules". ElonX.net. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Crew Dragon". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "NASA astronauts launch from U.S. soil for first time in nine years". Spaceflight Now. 30 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ @jeff_foust (23 July 2020). "McErlean: NASA's plans call for reusing the Falcon 9 booster from the Crew-1 mission on the Crew-2 mission, and to reuse the Demo-2 capsule for Crew-2 as well" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Crew-1 Makes Nighttime Splashdown, Ends Mission". NASA. 2 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The private Inspiration4 astronauts on SpaceX's Dragon may have an epic view ... from the toilet". Space.com. 14 September 2021. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ @SpaceX (13 January 2021). "Splashdown of Dragon confirmed, completing SpaceX's 21st @Space_Station resupply mission and the first return of a cargo resupply spacecraft off the coast of Florida" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (25 October 2021). "What You Need to Know about NASA's SpaceX Crew-3 Mission". NASA. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (6 October 2021). "SpaceX is adding two more Crew Dragons to its fleet". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Kanayama, Lee (16 September 2022). "SpaceX and NASA in final preparations for Crew-5 mission". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b "NASA's SpaceX Crew-9 Mission Overview News Conference". NASA. 26 July 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "Live coverage: SpaceX crew capsule set to move to new space station docking port". Spaceflight Now. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Ralph, Eric (9 November 2021). "SpaceX Dragon returns astronauts to Earth after record-breaking spaceflight". Teslarati. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Megan to reuse Bob's demo-2 seat in crew-2 mission". Al Jazeera. 20 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Thomas Pesquet first ESA astronaut to ride a Dragon to space". ESA Science and Exploration. 28 July 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Second phasing burn complete". Twitter. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Rogozin says Crew Dragon safe for Russian cosmonauts". SpaceNews. 26 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Saudi astronauts to research cancer, cloud seeding, microgravity in space". Al Arabiya English. 23 March 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Block 5 – Axiom Mission 3 (AX-3)". Next Spaceflight. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Polaris Dawn mission set to launch early Friday morning after delays". Fox 35 Orlando. Orlando, Florida. 3 September 2024. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Niles-Carnes, Elyna (6 August 2024). "NASA Adjusts Crew-9 Launch Date for Operational Flexibility – NASA's SpaceX Crew-9 Mission". NASA. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "NASA decides to keep 2 astronauts in space until February, nixes return on troubled Boeing capsule". AP News. 24 August 2024. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (12 August 2024). "SpaceX announces first human mission to ever fly over the planet's poles". Ars Technica. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ Niles-Carnes, Elyna (17 December 2024). "NASA Adjusts Crew-10 Launch Date". NASA. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "NASA Shares its SpaceX Crew-10 Assignments for Space Station Mission – NASA". Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ @NASASpaceOps (9 August 2024). "Axiom Mission 4 (Ax-4), the fourth private astronaut mission to the @Space_Station, now is targeted to launch no earlier than Spring 2025 from @NASAKennedy in Florida" (Tweet). Retrieved 9 August 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Niles-Carnes, Elyna (15 October 2024). "NASA Updates 2025 Commercial Crew Plan". NASA. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ "VAST Announces the Haven-1 and VAST-1 Missions". Vast Space. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ NASA Space Operations [@NASASpaceOps] (20 October 2023). "With Axiom Mission 3 scheduled to liftoff from Florida no earlier than January 2024, @NASA, @Axiom_Space, & @SpaceX teams are now targeting no earlier than October 2024 to launch Axiom Mission 4 to the @Space_Station" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Jared Isaacman, who led the first all-private astronaut mission to orbit, has commissioned 3 more flights from SpaceX". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Berger, Eric (3 June 2022). "NASA just bought the rest of the space station crew flights from SpaceX". Ars Technica. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Dragon CRS-21 – CRS-35". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (14 July 2022). "SpaceX launches cargo Dragon mission to ISS". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

After CRS-25, the next commercial cargo mission is NG-18, a Northrop Grumman Cygnus mission tentatively scheduled for mid-October. The SpaceX CRS-26 Dragon mission will follow late in the year, delivering among other cargo a set of solar arrays to be installed on the station by spacewalking astronauts.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (26 November 2022). "SpaceX launches Dragon cargo ship to deliver new solar arrays to space station – Spaceflight Now". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Wall, Mike (9 June 2023). "SpaceX Dragon breaks 2 space shuttle orbital records". Space.com. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Graf, Abby (8 November 2024). "Dragon Spacecraft Boosts Station for First Time". NASA. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ a b c d "NASA Orders Additional Cargo Flights to Space Station". NASA. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Block 5 | CRS SpX-32". nextspaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Block 5 | CRS SpX-33". nextspaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Block 5 | CRS SpX-34". nextspaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Block 5 | CRS SpX-35". nextspaceflight.com. Retrieved 26 November 2024.

- ^ "NASA Selects International Space Station US Deorbit Vehicle – NASA". Retrieved 27 June 2024.