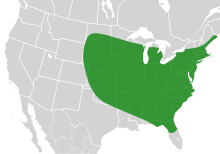

The two-spotted bumble bee (Bombus bimaculatus) is a species of social bumble bee found in the eastern half of the United States and the adjacent south-eastern part of Canada. In older literature this bee is often referred to as Bremus bimaculatus, Bremus being a synonym for Bombus.[3] The bee's common name comes from the two yellow spots on its abdomen.[4] Unlike many of the other species of bee in the genus Bombus, B. bimaculatus is not on the decline, but instead is very stable. They are abundant pollinators that forage at a variety of plants.

| Two-spotted bumble bee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Genus: | Bombus |

| Subgenus: | Pyrobombus |

| Species: | B. bimaculatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bombus bimaculatus | |

| |

| The range of Bombus bimaculatus in the US. | |

Taxonomy and phylogeny

editBombus bimaculatus is in the subgenus Pyrobombus, which is closely related to the subgenera Alpinobombus and Bombus out of the 15 total. Within Pyrobombus, B. bimaculatus is most closely related to B. monticola, B. sylvicola, and B. lapponicus.[5] Additionally, B. bimaculatus can oftentimes be confused with B. impatiens and B. griseocollis, as their colorations are very similar.[6]

Identification

editBombus bimaculatus was first described by Ezra Townsend Cresson, an American entomologist, in 1863.

Workers look very similar to queens, with the two mainly distinguished by size. Sometimes large workers can be mistaken for small queens, especially toward the end of the season when workers have grown larger and new queens emerge. Queens have a black face with a triangular patch of yellow hairs on the vertex. Their thorax is yellow except for a shining area on the disc that is bordered by black hairs. Their venter is black with some yellow hairs on the legs.[7]

Male faces have intermixed black and yellow hairs. They resemble females in most markings, except their tergite 2 has more yellow lateral hairs than the female whose tergite 2 has black edges and few yellow lateral hairs.[7]

The size of the radial cell in the wing differs for each. Workers have the smallest, ranging from 2.5 to 3.6 mm. Males are slightly bigger at 2.6–3.6 mm. Queens have the largest at 3.4–4.1 mm.[7]

Distribution and habitat

editB. bimaculatus is mainly found in eastern temperate forest regions throughout the United States and the southeastern part of Canada. It can also live in the coastal plains of the southeastern United States, the eastern Boreal forest, and the eastern Great Plains.[8]

This bee lives in underground nests, preferably in or around wooden areas and gardens. Nests can be anywhere from 6 inches to a foot below the surface. Tunnels traveling to the nest range from 9 inches to 4 feet long.[9] B. bimaculatus can also nest above ground or in cavities. Bees do not build nests and instead rely on finding abandoned rodent dens, hollow logs, suitable man-made structures, or tussocks. Queens will hibernate in loose dirt or rotting logs.[8]

This bumble bee is very common and has been experiencing steady growth unlike many other bumble bees that are in decline.[10]

Colony cycle

editBumble bee colonies are annual and a new colony is founded when a mated queen, the foundress, emerges from hibernation in the spring. Habitats for hibernation and colonies are different so she must find a suitable location to start her nest and she must do this on her own. She will provision it with pollen and nectar and then lay her eggs. This first brood will become non-reproducing female workers. At this time the queen must alternate between incubating the larvae and foraging for more provisions. Thus, this is the most vulnerable time for a fledgling colony.[6][8] Alternatively, some queens will not have mated the previous year and her offspring will all be male.[11]

Eggs typically hatch after four days and spend two weeks feeding on stored provisions before pupating. After another two weeks the pupae will have developed into adults. Once the workers emerge, queens will forage less and spend more time laying eggs. For B. bimaculatus, workers typically emerge in May and peak in July. Workers are responsible for brood care, foraging, regulating nest temperature and defending the nest. Males emerge last in June and peak in July. Unlike workers who stay and care for the brood, males will soon leave the nest after maturation to seek mates. New queens are produced at about the same time as males, and will forage extensively to build reserves for their overwintering. Unlike males that leave the nest and do not return, new queens will return to the nest at night.[6][8]

B. bimaculatus is one of the earliest bumble bee species to emerge, with queens being sighted as early as February. By the time fall arrives, newly mated queens will all be hibernating to repeat the cycle the following spring. Workers, males, and foundresses will have died. B. bimaculatus's colonies emerge quickly and die quickly in comparison with other bumble bee species.[6][8]

Behavior

editMale incubation

editMale B. bimaculatus can help care for larvae during the first days, or even weeks, of their life. Though female workers are mainly responsible for brood care, males cannot fly for the first 24 hours of their life so they cannot leave the nest. Incubating larvae is a potential opportunity for males to exercise their flight muscles. They assume the same position on the cocoon as females would and pump their abdomen to facilitate heat flow from their thorax to their abdomen to the brood. Male incubation may be more significant towards the end of the season when there are fewer workers to incubate larvae.[12]

Mating

editB. bimaculatus mate outside the nest with males patrolling in circuits, searching for a queen to mate with.[8] Most queens only mate once; however, there are some queens who mate multiple times and have offspring of multiple paternity.[13]

Foraging

editB. bimaculatus queens forage on Aquilegia flowers. The queens hang upside down on stamens, clutch the filament with their forelegs, and scrape off pollen using their middle and hind legs. Workers enter the Aquilegia spurs by pushing their head and part of their thorax into the spur's mouth. They then extend the maxillae and tongue into the spur to drink nectar, repeating this process on multiple spurs of the same plant before visiting the next one.[14]

B. bimaculatus queens' probosces range from 10.53 to 12.19 mm in length, which has little overlap with other Bombus species. This may potentially be the reason why B. bimaculatus are such abundant pollinators.[14]

Research comparing B. bimaculatus to Xylocopa virginica, a carpenter bee, found that the former learned faster and had more flexible foraging patterns. It was hypothesized that B. bimaculatus being a social bee could have individuals specialize in either foraging for nectar or pollen, instead of having to worry about both in overall food collection as the nonsocial carpenter bees needed to do.[15]

Mimicry and camouflage

editSeveral fly species are Batesian mimics of bumble bees, including robber flies, flower flies, deer bot flies, and bee flies. Some species of beetles, moths, sawflies and even other bees will mimic bumble bees. Additionally, the bumble flower beetle does not mimic the bumble bee's coloration but its buzzing flight sound.[8]

Bumble bees are not only mimicked by other insects, but also take on similar color patterns to each other in a form of Müllerian mimicry when multiple bumble bee species are found in the same region. B. bimaculatus is in the same group as B. impatiens, B. griseocollis, B. affinis, B. vagans, B. sandersoni, B. perplexus and B. fraternus. They all have a predominantly yellow thorax with a darker central spot.[8]

Nests typically do not need camouflage as they are hidden underground or in cavities.[8]

Interactions with other species

editDiet

editBumble bees eat nectar and pollen from plants. B. bimaculatus is known to pollinate a wide variety of plants, but they seem to have favorites. Queens can be found on willow and plum. Workers are found on red clover and mint. Males are found on mint and sweet clover.[7]

As a species they have been found foraging at the following plants:

- Zenobia pulverulenta[16]

- Gelsemium sempervirens[17]

- Lyonia lucida[18]

- Solanum dulcamara[19]

- Aquilegia species[19]

- Dicentra species[14]

- Mertensia species[14]

- Pedicularis species[14]

- Aesculus glabra[14]

- Camassia scilloides[14]

- Delphinium tricorne[14]

- Hydrophyllum appendiculatum[14]

Predators

editPredators of bumble bees include crab spiders, Florida black bears, ambush bugs, robber flies, dragonflies, assassin bugs, and some wasp species.[8] Crab spiders ambush B. bimaculatus at flowers, paralyze them, and then eat them.[8] Florida black bears eat B. bimaculatus most abundantly in the spring, and continue to eat them to a lesser extent in the summer.[20]

Defense

editB. bimaculatus will defend its nests against intruders, such as Psithyrus variabilis, a cuckoo bumble bee. In an experiment, a female P. variabilis was placed in a B. bimaculatus nest. Workers quickly recognized her as an intruder, halted their work and attacked her when she entered the inner part of the nest.[21]

Oftentimes though, B. bimaculatus are content to ignore intruders, such as Psithyrus labrosius. Like P. variabilis, P. labrosius also is a cuckoo bumble bee. It will attack Bombus vagans, but not B. bimaculatus though they are in the same subgenus, Pyrobombus.[21][22]

B. bimaculatus queens can kill each other when dueling. Queens can also be hostile to unrelated workers of their own species by squirting feces in their faces.[11]

Parasites

editBrachycoma sarcophagina is an ectoparasitoid that will consume B. bimaculatus bees from the outside. Female B. sarcophagina deposit young larvae on B. bimaculatus larvae. B. sarcophagina larvae will not begin consuming their host until the host has begun spinning its cocoon.[23]

Tracheal mites, will parasitize multiple Bombus species, but strongly prefer B. bimaculatus. Mites were recovered from the autosomal air sacs of bumble bees. These mites can affect behavior and reduce longevity, which may cause further stress to colonies already facing difficulties.[24]

Conopid flies also parasitize B. bimaculatus. Male bees were less likely to be parasitized than workers, and larger bees were more likely to be parasitized than smaller bees.[25]

B. bimaculatus is also parasitized by a bumble bee of the subgenus Psithyrus, Bombus citrinus, a brood parasite.[8]

Phoresy

editKuzinia, Scutacarid, and Parasitid mites were found on B. bimaculatus bees. Scutacarid and Parasitid mites were found in the propodia, the first abdominal segment in bees.[24] These mites, being phoretic, likely just use the bee as a means of transport. It is unknown what effect, either detrimental or beneficial, these mites may have on the bee.

Diseases

editB. bimaculatus can be infected with Nosema bombi, a microsporidian. This bee can also be infected by other fungal species. It is unknown how detrimental such an infection is to the bee's health.[24] Compared to other bumble bees that are in decline, B. bimaculatus has a lighter infection, which may be the reason why it is experiencing stable growth compared to the decline in other Bombus species. However, the reason for the difference in infection is unknown.[26]

B. bimaculatus can also be infected by Crithidia bombi and Apicystis bombi. Both are protozoans, but C. bombi is known to hinder colony creation, decrease host lifespan and colony fitness, and have a negative effect on workers' behavior. This can cause undue stress on colonies, leading to a species' decline.[24]

Microbiome

editThe gut bacteria of B. bimaculatus was isolated and include Snodgrassella alvi and Gilliamella apicola strains.[27] B. bimaculatus had more gut bacteria from environmental sources, and less core bacteria compared to other bumble bee species. B. bimaculatus had more core bacteria when collected from farms as opposed to collection from semi-natural habitats.[28]

Human importance

editPollinator

editB. bimaculatus is an important pollinator in temperate forest regions as it is still abundant, unlike many other species of honey and bumble bees. They also pollinate a wide variety of plants. In addition, bumble bees can continue foraging even under sub-optimal conditions such as rain or clouds.[6] B. bimaculatus is capable of flying even at 7 °C.[29] This makes the continued growth and stability of B. bimaculatus particularly valuable.

Sting

editOnly female bees have a sting, males do not. Bumble bees typically only sting when defending their nest or when captured. Allergies to bumble bee stings are much less common than allergies to honey bee stings though the venom composition is similar. B. bimaculatus venom contains additional proteins, including acrosin and a tryptic amidase related to clotting enzymes.[30]

References

edit- ^ Hatfield, R.; Jepsen, S.; Thorp, R.; Richardson, L.; Colla, S. (2014). "Bombus bimaculatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T44937719A69000240. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T44937719A69000240.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Bombus bimaculatus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ^ Michener, Charles Duncan (1974-01-01). The Social Behavior of the Bees: A Comparative Study. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674811751.

- ^ Brian Devore (July–August 2009). "Pollinators". Department of Natural Resources: 12.

- ^ Cameron, S. A.; Hines, H. M.; Williams, P. H. (May 2007). "A comprehensive phylogeny of the bumble bees (Bombus)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 91 (1): 161–188. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00784.x.

- ^ a b c d e Colla, Sheila; Richardson, Lief; Williams, Paul (March 2011). "Bumble Bees of the Eastern United States" (PDF). The Xerces Society. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Medler, John Thomas; Carney, D. W. (1963). "Bombus bimaculatus Cresson". Bumblebees of Wisconsin: (hymenoptera: apidae). Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Wisconsin. pp. 21–22. OCLC 1008565077.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Williams, Paul H.; Thorp, Robbin W.; Richardson, Leif L.; Colla, Sheila R. (2014-03-23). Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400851188.

- ^ Plath, O. E. (1 January 1922). "Notes on the Nesting Habits of Several North American Bumblebees". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 29 (5–6): 189–202. doi:10.1155/1922/34572. hdl:1721.1/96241.

- ^ Colla, Sheila R.; Gadallah, Fawziah; Richardson, Leif; Wagner, David; Gall, Lawrence (1 December 2012). "Assessing declines of North American bumble bees (Bombus spp.) using museum specimens". Biodiversity and Conservation. 21 (14): 3585–3595. Bibcode:2012BiCon..21.3585C. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0383-2. S2CID 13056138.

- ^ a b Plath, O. E. (1923). "Breeding Experiments with Confined Bremus (Bombus) Queens". Biological Bulletin. 45 (6): 325–341. doi:10.2307/1536729. JSTOR 1536729.

- ^ Cameron, Sydney A. (October 1985). "Brood care by male bumble bees". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 82 (19): 6371–6373. Bibcode:1985PNAS...82.6371C. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.19.6371. PMC 390717. PMID 16593608.

- ^ Payne, C. M.; Laverty, T. M.; Lachance, M. A. (1 November 2003). "The frequency of multiple paternity in bumble bee (Bombus) colonies based on microsatellite DNA at the B10 locus". Insectes Sociaux. 50 (4): 375–378. doi:10.1007/s00040-003-0692-2. S2CID 38261887.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Macior, Lazarus W. (1978). "Pollination Ecology of Vernal Angiosperms". Oikos. 30 (3): 452–460. Bibcode:1978Oikos..30..452M. doi:10.2307/3543340. JSTOR 3543340.

- ^ Dukas, Reuven; Real, Leslie A. (August 1991). "Learning foraging tasks by bees: a comparison between social and solitary species". Animal Behaviour. 42 (2): 269–276. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80558-5. S2CID 53161274.

- ^ Dorr, Laurence J. (1981). "The Pollination Ecology of Zenobia (Ericaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 68 (10): 1325–1332. doi:10.2307/2442731. JSTOR 2442731.

- ^ Adler, Lynn S.; Irwin, Rebecca E. (1 January 2006). "Comparison of Pollen Transfer Dynamics by Multiple Floral Visitors: Experiments with Pollen and Fluorescent Dye". Annals of Botany. 97 (1): 141–150. doi:10.1093/aob/mcj012. PMC 2000767. PMID 16299005.

- ^ Benning, John W. (October 2015). "Odd for an Ericad: Nocturnal Pollination of Lyonia lucida (Ericaceae)". The American Midland Naturalist. 174 (2): 204–217. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-174.2.204. S2CID 86085087.

- ^ a b Macior, Lazarus Walter (1966). "Foraging Behavior of Bombus (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in Relation to Aquilegia Pollination". American Journal of Botany. 53 (3): 302–309. doi:10.2307/2439803. JSTOR 2439803.

- ^ Maehr, David S.; Brady, James R. (1984). "Food Habits of Florida Black Bears". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 48 (1): 230–235. doi:10.2307/3808478. JSTOR 3808478.

- ^ a b Frison, Theodore H. (1 June 1926). "Contribution to the Knowledge of the Interrelations of the Bumblebees of Illinois with Their Animate Environment". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 19 (2): 203–235. doi:10.1093/aesa/19.2.203.

- ^ Lillie, Frank Rattray; Moore, Carl Richard; Redfield, Alfred Clarence (1922-01-01). The Biological Bulletin. Lancaster Press, Incorporated.

- ^ Goulson, Dave (2003). Bumblebees: Their Behaviour and Ecology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852607-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Kissinger, Christina N.; Cameron, Sydney A.; Thorp, Robbin W.; White, Brendan; Solter, Leellen F. (July 2011). "Survey of bumble bee (Bombus) pathogens and parasites in Illinois and selected areas of northern California and southern Oregon". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 107 (3): 220–224. Bibcode:2011JInvP.107..220K. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2011.04.008. PMID 21545804.

- ^ Malfi, Rosemary L.; Roulston, T'Ai H. (February 2014). "Patterns of parasite infection in bumble bees ( Bombus spp.) of Northern Virginia: Parasitism in bumble bees of Virginia". Ecological Entomology. 39 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1111/een.12069. S2CID 86392918.

- ^ Tripodi, Amber D.; Cibils-Stewart, Ximena; McCornack, Brian P.; Szalanski, Allen L. (April 2014). "Nosema bombi (Microsporidia: Nosematidae) and Trypanosomatid Prevalence in Spring Bumble Bee Queens (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Bombus ) in Kansas". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 87 (2): 225–233. doi:10.2317/JKES130730.1. hdl:2097/18657. S2CID 55303192.

- ^ Kwong, Waldan K.; Moran, Nancy A. (1 June 2013). "Cultivation and characterization of the gut symbionts of honey bees and bumble bees: description of Snodgrassella alvi gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Neisseriaceae of the Betaproteobacteria , and Gilliamella apicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of Orbaceae fam. nov., Orbales ord. nov., a sister taxon to the order ' Enterobacteriales ' of the Gammaproteobacteria". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 63 (6): 2008–2018. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.044875-0. PMID 23041637.

- ^ Cariveau, Daniel P; Elijah Powell, J; Koch, Hauke; Winfree, Rachael; Moran, Nancy A (December 2014). "Variation in gut microbial communities and its association with pathogen infection in wild bumble bees (Bombus)". The ISME Journal. 8 (12): 2369–2379. Bibcode:2014ISMEJ...8.2369C. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.68. PMC 4260702. PMID 24763369.

- ^ Goller, Franz; Esch, Harald (1 May 1990). "Comparative Study of Chill-Coma Temperatures and Muscle Potentials in Insect Flight Muscles". Journal of Experimental Biology. 150 (1): 221–231. doi:10.1242/jeb.150.1.221.

- ^ Hoffman, D; Jacobson, R (March 1996). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XXVII: Bumblebee venom allergy and allergens". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 97 (3): 812–821. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(96)80159-x. PMID 8613638.

External links

edit- [1] A color key pattern by Dr. Paul Williams to help identify different bumble bee species

- [2] Discover Life's online tool to identify bumble bees

- [3] High quality images of Pyrobombus bees, including B. bimaculatus

- [4] Video of a B. bimaculatus queen creating an egg cup, laying an egg and sealing it

- Hatfield, R.; Jepsen, S.; Thorp, R.; Richardson, L.; Colla, S. (2014). "Bombus bimaculatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T44937719A69000240. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T44937719A69000240.en. Retrieved 4 May 2021.