This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2012) |

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Korean: 진실·화해를위한과거사정리위원회), established on December 1, 2005, is a South Korean governmental body responsible for investigating incidents in Korean history which occurred from Japan's rule of Korea in 1910 through the end of authoritarian rule in South Korea with the election of President Kim Young-sam in 1993.

| Truth and Reconciliation Commission | |

| Hangul | 진실·화해를위한과거사정리위원회 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Jinsil hwahaereul wihan gwageosa jeongni wiwonhoe |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chinsil hwahae rŭl wihan kwagŏsa chŏngni wiwŏnhoe |

The body has investigated numerous atrocities committed by various government agencies during Japan's occupation of Korea, the Korean War, and the authoritarian governments that ruled afterwards. The commission estimates that tens of thousands of people were executed in the summer of 1950.[1][2] The victims include political prisoners, civilians who were killed by US forces, and civilians who allegedly collaborated with communist North Korea or local communist groups. Each incident investigated is based on a citizen's petition, with some incidents having hundreds of petitions. The commission, staffed by 240 people with an annual budget of $19 million, was expected to release a final report on their findings in 2010.[3]

Objective

editOperating under the Framework Act on Clearing up Past Incidents for Truth and Reconciliation,[4] the purpose of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRCK) is to investigate and reveal the truth behind violence, massacres, and human rights abuses that occurred throughout the course of Japan's rule of Korea and Korea's authoritarian regimes.

Background

editKorea's history during the last 60 years as it transitioned from a colony to a democracy has been filled with violence, war, and civil disputes. With Japan's defeat in World War II in 1945, Korea was divided in two at the 38th parallel, with administration of the north side given to the Soviet Union, while the south side was administered by the United States (see Gwangbokjeol). In 1948, two separate governments formed, each claiming to be the legitimate government of all of Korea.

South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea) was formally established on August 15, 1948, by Korean statesman and authoritarian dictator Syngman Rhee. The establishment of a legitimate government body in South Korea was marked by civil unrest and several instances of violence (see Jeju Uprising, Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion). Two years after the establishment of the Republic of Korea, North Korean forces invaded South Korea, precipitating the Korean War.

The war ended with the Korean Armistice Agreement, signed on July 27, 1953. Syngman Rhee attempted to maintain his control of the government by pushing through constitutional amendments, declaring martial law, and jailing members of parliament who stood against him. His rule came to an end in April 1960 as protests throughout Korea forced him to resign on April 26 (see April Revolution).

After Syngman Rhee's resignation, an interim government briefly held power until Major General Park Chung-hee took control through a military coup on May 16, 1961. Amid pressure from the United States, the new military government decided to hold elections in 1963 to return power to a civilian government. Park Chung-hee ran for president in those elections and was narrowly elected. In 1967 and 1971, Park Chung-hee ran for re-election and won using a constitutional amendment that allowed a president to serve more than two terms.

During his rule, Korea saw dramatic economic growth and increased international recognition as it maintained close ties with, and received aid from, the United States. On October 17, 1972, Park Chung-hee declared martial law, dissolving the national assembly and putting forth the Yushin Constitution, which gave the president effective control of parliament, leading to civil unrest and the jailing of hundreds of dissidents.

In 1979, Park Chung-hee was assassinated by Korean NIS Director Kim Jaegyu, which led to another military coup by Major General Chun Doo-hwan. This coup led to more civil unrest and government clampdowns (see Gwangju Massacre). Public outrage over government killings led to more popular support for democracy.

In 1987, Roh Tae-woo, a colleague of Chun Doo-hwan, was elected president. During his rule, he promised a more democratic constitution, a wide program of reforms, and popular election of the president. In 1993, Kim Young-sam was elected president, becoming the first civilian president in 30 years.

Korea under Japanese rule

editIndependence movements immediately preceding and during the Japanese occupation, and efforts by overseas Koreans to uphold Korea's sovereignty, are described below.

Abuses of governmental power against the Guro farmland owners

editThe TRCK verified that the government abused its power by fabricating facts concerning the owners of farmland in Guro. In 1942, the Japanese Ministry of Defense confiscated the land of 200 farmers in the Guro area. The farmers continued to use the land under the supervision of the Central Land Administration Bureau, even after Korea's liberation in 1945. Beginning in 1961, the government constructed an industrial complex and public housing on the land. In 1964, the farmers claimed rightful ownership of the land and brought several civil action lawsuits against the government. The rulings for many of these cases were not issued until after 1968.

The government began appealing the rulings in 1968, appealing three cases in 1968 and one case in 1970. The government accused the defendants of defrauding the government and launched an investigation. The prosecutor arrested the accused without warrants or explanation, and coerced them into surrendering their rights through the use of violence. However, the investigation did not uncover any evidence that supported the accusations.

The lack of evidence and the fact that the civil action suit rulings were already passed did not deter the government from demanding that the defendants surrender their rights. After 40 of the defendants refused to obey the demand, several lawsuits were brought against them. The prosecution accused them of fraud and attempted to punish the defendants by holding criminal trials.

Official documents verify that the defendants were eligible for farmland distributed by the government under the Farming Land Reform Act and, therefore, did not defraud the government as alleged. Although most of the defendants were cleared of suspicion, the government conducted a second investigation to punish them.

The Commission recommended that the government officially apologize, hold a retrial, and implement relevant measures for the defendants.[citation needed]

Korean nurses and miners in Germany contributed to Korea's economic growth

editAccording to the commission's findings, Korean miners were recruited and dispatched to West Germany.[5] The Korean government was involved in both their recruitment and dispatch. A total of 7,936 Korean miners were relocated to Germany between 1963 and 1977. In addition, a total of 10,723 registered Korean nurses were dispatched to West Germany beginning in the late 1950s until 1976. The Korean government also played roles in the later stage of this period.

Between 1965 and 1975, the Korean miners and registered nurses in West Germany wired a total of USD 101,530,000 back to Korea, which comprised 1.6%, 1.9%, and 1.8% of Korea's total export amount in 1965, 1966, and 1967, respectively. Considering that the foreign exchange rate was 100% and the earned dollars in the past were valued much higher than today, the Korean miners and nurses in West Germany were estimated to have greatly contributed to Korea's economic growth. The commission found the allegations false that the Korean government received commercial loans successfully from West Germany in return for forcibly depositing the Korean miners and registered nurses’ income in Commerzbank in West Germany.

From Korea's total commercial loan of DM 150,000,000 from West Germany, the West German government issued DM 75,000,000 under the "protocol concerning economic and technical cooperation between the government of the Republic of Korea and Germany" to guarantee the invoice payments of imported German industrial facilities. It was also found that approximately 60% of the dispatched Korean miners and nurses have resided in West Germany and other nations, and contributed greatly to forming and developing Korean communities in their respective residing nations.

The commission's findings report that the dispatch of Korean miners and nurses to West Germany was considered to be the Korean government's first attempt to relocate Korea's workforce overseas. Its impact on Korea's economic growth has been greatly underestimated and inadequately documented. A significant finding reveals that the commercial loan from West Germany was not a result of the German Commerzbank forcefully holding wages of the dispatched Korean miners and nurses.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that the Korean government collect relevant documents and make full use of them for educational purposes, as well as to take adequate actions to prevent the spread of false information.

Allied occupation

editThe Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that the reputations should be cleared and compensation paid to the families of those who had been unlawfully victimized by authorities in the Daegu October Incident.[6]

Dictatorship periods

editThe commission's scope included political killings, torture, forced disappearances, unfair trials, and other human rights abuses committed through the illegal exercise of state power. This period begins on August 15, 1945, and lasts until the end of military rule following the June Democratic Uprising in 1987.

Sometimes, the commission deals with cases that have already been ruled on in court, but qualify for new trials and need to be reinvestigated for truth, as well as cases that the Presidential Truth Commission on Suspicious Deaths investigated inconclusively and requested the TRCK to reinvestigate.

Fabricated case against Seo Chang-deok

editSeo Chang-deok, a fisherman, was kidnapped to North Korea in 1967 while on a regular fishing trip and returned home to the South. Seventeen years later, security forces in Jeonju arrested Seo without charges using a falsified confession, which was the result of illegal confinement and torture. Seo was sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment and his human rights were violated.

Fabricated espionage case against five fishermen kidnapped by North Korea

editThe TRCK's investigation into North Korea's kidnapping of the five fishermen found that the organization overseeing investigations illegally detained and interrogated the returning men and their families. Based on the fabrications, the detainees were falsely accused and punished for espionage.

On July 22, 1967, the crew of the fishing vessel Song-yang, operating off the coast of the island of Soyeonpyeongdo, were kidnapped by a North Korean coastal defense ship. After a month of captivity, the North Koreans released the fishermen on the west coast. They were met by police officers, who promptly questioned them before releasing them without charges.

In December 1968, a year after the kidnapping, a special investigation organization interrogated, without a warrant, five of the fishermen regarding their work at the time of the incident. While it was determined that sea currents carried the Song-yang within range of the North Korean coastal defense ship, the organization accused the men of escaping to North Korea and then infiltrating South Korea for propaganda purposes. The organization illegally detained the men and one of their wives for 88 days. The wife was accused of receiving counterfeit money and coded messages from three unidentified men thought to be spies, as well as failing to notify the authorities.

During the fishermen's imprisonment, the organization subjected them to abusive interrogation tactics, including torture and assault. Initial reports indicated that the Song-yang was in South Korean waters at the time of the incident, but the interrogators coerced the fishermen into signing false statements saying otherwise. The organization also falsified charges against Ms. Kim, the wife, after they detained her on accusations of accepting counterfeit money. No specific evidence of the unidentified men existed, nor was there any evidence of anyone of that nature visiting her house. The 500,000 won of counterfeit money and the coded message were not found, nor mentioned in any investigative document, and no report describing such an incident was ever submitted to the court.

Based on the charges, the fishermen were sentenced to serve between one and five years in prison. Ms. Kim was sentenced to one year in prison and one year of probation. During their sentences, their families faced discrimination due to the stigma of being related to a suspected North Korean spy. This ostracism made it impossible for many family members to obtain jobs. Besides the social stigma they experienced after their release, the fishermen suffered psychological trauma from torture and abusive treatment.

The special investigation organization did not limit the scope of the probe to the fishermen. Instead, they extended their interrogations to village acquaintances. Such wide-sweeping investigations further ostracized the men and disrupted the amicable relations of the community by exacerbating the hostility and discrimination.

The TRCK recommended that the government apologize to the victims and re-examine the situation, or take action to repair the damage and restore the honor of the victims and their families.[citation needed]

Detainment and torture of Lim Seong-kook

editThe TRCK ascertained Lim Seong-kook was forcefully taken by the Gwangju security forces and tortured during 28 hours of detention. TRCK found that the Gwangju security forces did not have investigative jurisdiction and they additionally abused their power by repeatedly torturing Lim Seong-kook during the interrogation. He died two weeks after his release.

Without a warrant, the security forces forcibly detained Lim Seong-kook in July 1985 and placed him under custody for an espionage charge based on a suspicion that he might be in contact and cooperating with North Korean spies.[citation needed] The landlord's family, with whom Lim had a close relationship until his arrest, was sentenced to imprisonment for meeting his brother, who had been dispatched as a spy from North Korea in 1969.[citation needed]

The security forces’ interrogators in Gwangju were aware of the restrictions of the judicial measurements while investigating civilians. Nevertheless, they illegally arrested and interrogated Lim.[clarification needed] TRCK collected statements from eyewitnesses and other sources, including the interrogators. TRCK found that Lim was lynched, and that this lynching was the main cause of his death. Lim suffered physically and emotionally after the security forces tortured him. He did not receive adequate medical treatment.[citation needed]

With Lim the main breadwinner, his family suffered financial difficulties after he died. Feeling discrimination from their neighbors, the family relocated to Gunsan, North Jeolla Province.[citation needed]

In the 21st century, Lim's family petitioned the Presidential Truth Commission on Suspicious Deaths and the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) to find out the truth concerning Lim's death. Their petitions were rejected because they either missed the application period or the statute of limitations had expired.[citation needed]

Lim's family testified that officials[clarification needed] discounted or did not believe their claim that his death was a result of the harsh interrogation from the security forces. They stated that they did not know which of the authorities was responsible for Lim's forceful abduction and torture. In particular, fear of further persecution for seeking the truth inhibited them from bringing attention to the case.[citation needed]

Coercion of The Dong-a Ilbo

editThe official government Truth and Reconciliation Commission determined that one of the more famous press suppression cases of the Park Chung-hee years, the "Dong-a Ilbo Advertising Coercion and Forced Layoff Case" during 1974 and 1975, was orchestrated by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA, now known as the Intelligence Service), and that The Dong-a Ilbo itself, the leading newspaper in Korea, went along with what was unjust oppression by the Yusin regime, as it was then called.

In a report issued October 29, the commission formally recommended that the state and The Dong-a Ilbo "apologize to those who were fired and make appropriate amends" for what the report defines as "a case in which the state power apparatus, in the form of the KCIA, engaged in serious civil rights violations."

According to the commission, the KCIA summoned companies with significant advertising contracts with The Dong-a Ilbo Company to the KCIA's facility in Seoul's Namsan neighborhood and had them sign written documents pledging to cancel their contracts with the company for advertisements with its various periodicals, including the daily Dong-a Ilbo, as well as with Dong-a Broadcasting, which Chun Doo-hwan later took from them.

Individuals who bought smaller advertisements with The Dong-a Ilbo expressing encouragement to the paper were either called in or physically detained by the KCIA and threatened with tax audits.

The commission cited The Dong-a Ilbo for "surrendering to the unjust demands of the Yusin regime by firing journalists at the government’s insistence, instead of protecting the journalists that had stood by the newspaper to defend its honor and press freedom." According to the report, the KCIA demanded, and The Dong-a Ilbo accepted, the condition that no less than five newspaper section chiefs always confer with the KCIA, before allowing the resumption of advertising.

On seven occasions between March and May 1975, The Dong-a Ilbo fired 49 journalists and "indefinitely suspended" the employment of 84 others. The commission cited executives at the time for "failing to admit that the firings were forced by the regime" and for "going along with suppression of press freedoms for claiming they were being fired for managerial reasons."

"Ultimately," the report said, The Dong-a Ilbo "will find it hard to avoid responsibility for hurting the freedom of the press, the livelihoods of journalists, and (its own) honor."

Later on the day the report was made public, members of the Struggle Committee to Defend Press Freedom at the Dong-a (Dong-a Teugwi), an organization of journalists who were fired at the time, met with the media in front of The Dong-a Ilbo company's offices along Seoul's Sejongno boulevard to read a statement calling on the government and the newspaper to "accept the recommendation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and apologize to us journalists, and take action commensurate with what happened to correct the damage."[7]

Many of the journalists suspended or fired from The Dong-a Ilbo later went on to found The Hankyoreh.[citation needed]

Falsified espionage charge against Lee Soo-keun

editLee Soo-keun, the former vice president of the Korean Central News Agency in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), was exiled to the Republic of Korea through the demilitarized zone on March 22, 1967. Lee then worked as an analyst at the KCIA until he was caught by KCIA agents en route to Cambodia under forged passports on January 27, 1969. After returning to South Korea, Lee was charged with violating the National Security Law and the Anti-communist Law by secretly collecting classified information and taking it out of the country, among other crimes.

A death sentence was imposed on Lee on May 10, 1969, and he was executed on July 2 of the same year. South Korea's Truth and Reconciliation Commission ascertained that the KCIA illegally confined Lee, thereby meeting the prerequisites for a retrial, abiding by provision 7 under Article 420 and Article 422 of the Criminal Law. The commission also said that the illegal confinement during the interrogation, and the fact that the prosecution relied solely on the defendant's statements, failed to satisfy the rules of evidence.

The commission recommended that the government make an official apology, restore of the honor of the dead, and retry the case in accordance with its findings.[citation needed]

Abduction of Taeyoung-ho fishing crew

editFive petitioners pleaded for a truth verification concerning the abduction cases of the Taeyoungho crews. The crews were forcibly taken away by North Korean coast guards when they were got caught fishing on the North Korean side of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL). They were found guilty by the South Korean authorities for violating the Anti-communist Law soon after they returned from their four-month detention in North Korea.

The commission found that the crews were illegally confined and tortured during their interrogations at the Buan Police Office, which qualified the case for a retrial. Additionally, the commission found that the espionage charges against the abductees were falsified, and that the prosecutions were pursued without sufficient evidence, based only on testimony from the defendants, which did not meet the rules of evidence.

The commission advised that the government officially apologize to the victims and have a retrial in accordance with its findings.[citation needed]

Falsified espionage charges against the family of Shin Gui-young

editShin Gui-young was sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment for allegedly collecting classified military information with orders from Shin Soo-young, the senior member of Chōsen Sōren in Japan. Found guilty, Shin was sentenced at the Busan District Court in 1980 and released upon completion of his 10-year term.[citation needed]

Aram-hoe Incident

editPark Hae-jeon, et al., concerned 11 residents of Geumsan and Daejon, whose occupations included teacher, student, salaryman, soldier, and housewife, had held regular meetings between May 1980 and July 1981 based on friendship originating from their school days. They were taken to the Daejeon Police Office and arrested soon afterwards for having inappropriate gatherings at which traitorous conversations took place. They were accused of violating the National Security Law by joining a treasonous organization and praising enemies of the nation, and sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment.

The commission found that the organizations concerned, including South Chungcheong Province’s Provisional Police Agency conducted illegal confinement and brutal torture, and improperly pressed charges on the victims without sufficient evidence. The TRCK recommended that the government retry the case and make an official apology to the victims.[citation needed]

Civilian massacres during the Korean War

editIllegal summary executions of civilians were practiced, often on a large scale, from August 15, 1945, up to the end of Korean War. Mass killings were conducted by various parties in both the North and South, as well as US forces who bombed civilians indiscriminately for fear of disguised enemy soldiers.

Ulsan massacre

editThe Ulsan Bodo League massacre was committed by the South Korean police against suspicious left-leaning civilians, most of them illiterate and uneducated peasants, who were misinformed when they registered themselves as Bodo League members. In the southeastern city of Ulsan, hundreds of people were massacred by South Korean police during the early months of the Korean War. In July and August 1950 alone, 407 civilians were summarily executed without trials.

On January 24, 2008, the former President of Korea Roh Moo-hyun apologized for the mass killings.

(See also the mass killings conducted against prison inmates who were suspected leftists, which took place at prisons in other cities such[8] as Busan, Masan and Jinju.)

Wolmido Incident

editThe commission concluded on March 11, 2008, that indiscriminate bombing by the US on[9][10] Wolmido Island, Incheon, Korea, on Sept. 10, 1950, caused severe casualties of civilians residing in the area. At the time, the United Nations attempted a sudden landing maneuver in Incheon to reverse the course of the war, and Wolmido Island was a strategically significant location that needed to be secured.[11]

Declassified US military documents provided evidence of the attack without acknowledging the civilian casualties. On Sept. 10, 1950, five days before the Inchon landing, 43 United States Air Force (USAF) aircraft dropped 93 napalm canisters over Wolmido's eastern slope to clear the way for American troops. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission ruled that the attack violated international conventions on war, accusing the US military of using indiscriminate force on three attacks in 1950 and 1951, in which at least 228 civilians, possibly hundreds more, were killed. The commission asked the country's leaders to seek compensation from the United States.[12] Surviving villagers were forced to evacuate their homes and did not return, since the island became designated as a strategically important military base even after the Korean War.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that the Korean government negotiate with the US government to seek compensation for those victimized by the incident. [13][14]

Bodo League massacre

editThe Bodo League[15] (National Guidance Alliance, 국민보도연맹; gukmin bodo rungmaeng, 國民保導聯盟) was established on April 20, 1949, in order to convert left-wingers residing in South Korea, including former members of South Korean Workers Party(남조선로동당; 南朝鮮勞動黨), and embrace them as citizens of the "democratic" South Korea. However, its goal was an apparent manipulative tactic of the right-wing South Korean government to identify potential communists within the South and eventually eliminate them by execution around the time of the Korean War.

Its headquarters was established on June 5, 1949, and regional branches were set up by the end of March the following year. In the course of recruiting members of the Bodo League, many innocent civilians were coerced to join by regional branches and governmental authorities trying to reach their allocated numbers.

Shortly after the Korean War broke out, Syngman Rhee's government became obsessed with the idea that communist sympathizers might cooperate with the communist North and become threats to the South, and ordered each police station to arrest those who had left-leaning tendencies. From July to September 1950, police authorities and special troops of South Korea were organized to strategically carry out the orders. In most cases, arrested Bodo League members or sympathizers were forcefully held in storage spaces near police stations for several days before being summarily executed at sites such as remote valleys in deep forest, isolated islands or abandoned mine areas.

The number of Bodo League members reached an estimated 300,000 nationwide before the Korean War. Several thousand civilians were illegitimately killed without due process. In addition, the families of the victims were branded as associated with communists and often targeted by a series of regimes suffering from extreme McCarthyism.[citation needed]

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission received 10,859 cases around the time of the Korean War. The committee received over 200 additional cases, but it needed to amend the law in order to proceed. Rep. Kang Chang-il of the United Democratic Party (Republic of Korea) proposed a revision to the bill to prolong the time limit for a maximum of six months.[16]

Uljin massacre

editThe commission found that 256 people were killed in Uljin, Gangwon Province, by South Korea's police forces, the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), and the 3rd ROK Army after being accused of siding with local leftists. The massacre took place between September 26, 1950, and the end of December 1950. The victims were identified by historical documents, testimony by witnesses and petitioners, records from the Uljin police station, and field research conducted throughout the county.

Reserve troops from the 3rd Army selected about 40 village residents with leftist tendencies from Uljin police-station cells based on lists by right-wing organizations and village chiefs, summarily executed and buried them in Hujeong-ri's Budul Valley on October 20, 1950. The Uljin police released some of the accused between October and November 1950, but about 250 civilians were buried in Shinrim's Olsi Valley.

In the late fall of 1950, several Onjeong-myeon villagers were accused of providing food to fugitive relatives who had fled after being suspected of leftist tendencies. On November 26, 1950, the Onjeong police arrested suspects and confined them to a storage space. Twelve were executed en route to the Uljin police station in Sagye-ri, Buk-myeon, by police from Hadang.

The victims were accused of holding positions in North Korea's occupation authority, and were targeted for mass killings conducted by South Korean authorities when they re-entered the region. Most collaborators with North Korean forces had already crossed the border to the north at the time of the massacre, however, and civilians had joined the local leftists.

There were no clear distinctions to separate the guilty from the innocent, and many took the opportunity to eliminate personal opponents. The summary executions of civilians without adequate judicial process were crimes against humanity, and the victims' descendants experienced social discrimination in McCarthyist, pre-democratic South Korea.

The commission advised the government to apologize to the victims' families, to conduct human-rights education, and to hold memorial services for those who were wrongfully prosecuted and murdered.

Geumsan massacre

editThe commission found a total of 118 rightists, including civil servants, were killed by left-leaning regional self-defense forces, communist guerillas, and the North Korean People's Army in Geumsan County after North Korean troops entered the area, especially between July and November 1950.

On September 25, 1950, a number of right-wing personnel, including civil servants under the South Korean regional government, were brought to the ad hoc police entity in Geumsan, which was established by the North after its entry to the region. They were slaughtered before being buried at a nearby hill called Bibimi-jae. The massacre was carried out by members of the ad hoc police and North Korean troops on orders from the provisional police chief.

At dawn on November 2, 1950, a group of communist guerillas swarmed into the Buri-myeon police department controlled by the South, incinerated the building, and captured those inside. During the course of the assault, many villagers were accused of collaborating with the South, and 38 of them were executed.

Additional mass killings of civilians by communist partisans in locations including Seokdong-ri in Namyi-myeon, and Eumji-ri in Geumsan County, were also confirmed by the commission during the investigation. Most of the victims were accused of being affiliated with the South Korean governing entities before the North's entry into the region or of having right-leaning political loyalties. The accused included members of the Korean Youth Association (대한청년단; 大韓靑年團) and the Korean National Association (국민회; 國民會), both of which were representative right-wing political organizations in the peninsula.

In spite of the various accusations, the commission discovered the majority of casualties were committed due to personal animosities and a desire of the perpetrators to eliminate their adversaries. The commission's investigation found that the perpetrators of the Geumsan massacre were members of the regional self-defense forces, communist partisans, local leftists residing in the area, and North Korean troops who fell behind their main regiments.

The commission recommended revising the historical accounts kept in governmental archives in accordance with the commission's finding.[citation needed]

Gurye Massacre

editThe TRCK found that, between late October 1948 and July 1949 in Gurye County, shortly after the Yeo-Sun Incident, a large number of civilians were illegitimately killed as South Korean troops and police forces conducted military operations to subdue communist insurgents. These mass killings are considered separate from the Yeosun Incident. Approximately 800 civilians were massacred. 165 victims were identified, according to various historical records kept in Korea's National Archives, historical records of subjugating communist insurgents (공비토벌사; 共匪討罰史) in the South Korean Army Headquarters (1954), field research, and statements from witnesses. South Korean troops and police forces captured, tortured, and executed civilians accused of collaborating with local leftists or insurgents.

Villages located near insurgent bases were incinerated, and their residents were accused of collaboration before being executed during operations to "clean up" communist insurgents. A series of similar mass killings occurred between late October 1948 and early 1949 near Gurye, when the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 3rd Regiment of the South Korean Army were based in the region. The Gurye Police Office detained civilians suspected of collaborating with local communist partisans and commonly tortured their captives before executing them and concealing their bodies in nearby areas or on Mt. Bongseong. The members of the Korean Youth Association (대한청년단; 大韓靑年團) in Gurye also directly or indirectly abetted these systematic operations of mass killings by providing groundless accusations and supporting the extermination of those affiliated with communist guerillas or local leftists. They mostly assisted with the removal and burial of bodies after the executions.

Accusations against victims included joining a left-leaning organization, such as the Socialist Labor Party in South Korea (남로당; 南勞黨). Other accusations were as minor as residing near areas targeted by the military, or being related to suspected victims. South Korean troops and police forces commonly conducted indiscriminate arrests, detention, and imprisonment. They tortured and summarily executed people without adequate investigation or legitimate judicial process.

The martial law proclaimed at the time was not supported by any law and, thus, the administrative and judicial authorities of the chief commander under martial law were subject to revocation. Furthermore, administrative and judicial authority were arbitrarily interpreted and implemented by regional chiefs, which increased the number of civilian casualties. Even if martial law is considered legitimate, the principle of non-combatant immunity was neglected for the authority to execute innocent civilians. Perpetrators often practiced a type of extrajudicial punishment (즉결처분권; 卽決處分權) to carry out summary executions. This was often misunderstood to be the authority to arbitrarily kill civilians.

The commission found that the killing of innocent civilians by the public authorities in Yeosu and Suncheon greatly transgressed the constitutional legality given to the military and police force at the time. They failed in their sacred obligations of protecting the lives and property of civilians.

The commission advised the government to officially apologize to the bereaved families of the victims, restore the honor of the dead, revise historical records in accordance with its findings, and reinforce education in sustaining peace.[citation needed]

Massacre at Muan-gun

editThe TRCK verified that on October 3, 1950, leftists massacred 96 right-wing residents of Cheonjang-ri, Haejae-myeon, in Muan County. Around 10:00 pm on October 3, 1950, four regional leftist leaders drew up lists of right-wing residents to be executed. The selected families were bound and dragged by the leftist perpetrators to a nearby shore, where the perpetrators executed the adult family members using knives, clubs, bamboo spears, and farm implements before pushing them off a cliff near the shore. Children under the age of 10 were executed by being pushed into a deep well. While the commission identified 96 victims, including 22 children and 43 women, the total number may be as high as 151. The total number of perpetrators is estimated to be 54 leftists.

The Commission found that this incident offers an opportunity for self-examination in regard to the atrocities of war.[citation needed]

Ganghwa Massacre

editAround the time of the Third Battle of Seoul, the Ganghwa Regional Self-defense Forces assumed that, if North Korean troops occupied the region, those with left-leaning tendencies and their families would collaborate with the North. Therefore, preemptively eliminating a potential fifth column became a strategically beneficial objective.[citation needed]

Shortly before the retreat, the Chief of the Ganghwa Police and the Chief of the Ganghwa Branch Youth Self-defense Forces issued execution orders.[citation needed] These were followed by special measurements issued from the Gyeonggi Provincial Police Chief with regard to traitors.[citation needed] The mass executions carried out afterwards often occurred with the aid or tacit consent of South Korean and U.S. forces.[citation needed]

Shortly thereafter, some residents of Ganghwa and their families, were accused of treachery. They were captured by the Ganghwa Regional Self-defense Forces, and detained at the Ganghwa Police Station and its subordinate police branches. The detainees were tortured before being executed at remote sites scattered throughout the region. The possible number of casualties based on statements from witnesses, petitioners, and documents, was as high as 430.

Details of the incidents emerged when a group of residents registered their deceased family members as victims under the Korean War Veteran Memorial Law.

The TRCK concluded that the Ganghwa Regional Self-defense Forces were guilty of killing 139 civilians residing in the Ganghwa, Seokmo and Jumun island areas around the time of the January 4, 1951, recapture of Seoul by Communist forces.[citation needed] These summary executions of civilians without due process were considered to be a crime against humanity. Family members were presumed to be tainted by guilt by association. They suffered social stigma. While direct responsibility for the incidents may be directed at regional governments and civil organizations, the South Korean government was also held accountable since they neglected their obligations to administer and control the regional authorities’ activities.[citation needed] The Commission found that the Ganghwa Self-defense Forces, an organization outside the control of any U.S. or South Korean authorities, was provided with arms, which they then used to assault civilians. This action by the government[clarification needed] resulted in the deaths of innocent villagers. The Commission advised the government to officially apologize to the victims’ bereaved families, seek reconciliation between the victims and perpetrators, and arrange adequate emergency alternatives, considering Ganghwa's geographical circumstances.[citation needed]

Mass Murder of Accused Leftists in Naju

editTwenty seven petitioners filed for verification of a mass murder that took place in Naju, South Korea, on February 26, 1951. According to the petitioners, a total of 28 villagers were summarily executed at Cheolcheon-ri, Bonghwang—myeon in Naju without due process, having been accused of collaborating with communist guerillas.

The TRCK found that the Naju Police Special Forces were responsible for the atrocity, and recommended that the government officially apologize to the families of the victims, restore the honor of the dead, and implement preventive measures.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related massacres in the Gunwi, Gyeongju, and Daegu regions

editThe Commission determined that at least 99 local residents in Gunwi, Gyeongju, and Daegu were massacred between July and August 1950 by the military, local police, and CIC after being blacklisted or accused of being members of the Bodo League. In July 1950, dispatched CIC forces and local policemen arrested and temporarily detained members of the Bodo League at local police stations or detention centers. The detainees were categorized into three different groups before being transported to Naenam-myeon, Ubo-myeon, or Gunwi County and massacred.

The Commission recommended that the government issue an official apology, provide support for memorial services, revise official documents including family registries, and strengthen peace and human rights-related education.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related massacres in the Goryeong, Seongju, and Chilgok regions

editThe Commission found that a number of civilians were killed by the local police, military, CIC, and military police after being accused of cooperating with leftists or being a member of the Bodo League. The killings took place between July and August 1950 in the Goryeong, Seongju, and Chilgok regions of North Gyeongsang Province. Bodo League members were either arrested by local police or summoned to nearby police stations and detained. As North Korean troops advanced southward, the army and military police took custody of the detainees before killing them.

The Commission recommended that the government officially apologize to the families of the victims, support memorial services, revise family registries and other records, and provide peace and human rights education.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related massacres in Miryang, South Gyeongsang Province

editThe Commission ascertained that members of the Bodo League in the Miryang region were massacred by the local police and the South Gyeongsang Province CIC between July and August 1950. The victims were forcibly confined in various warehouses before being executed in August 1950.

The Commission recommended that the government officially apologize to the families of the victims, support memorial services, revise family registries and other records, and provide peace and human rights education.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related massacres in Yangsan, South Gyeongsang Province

editThe Commission found that regional members of the Bodo League and those in preventive detention were killed by the local police and CIC forces between July and August 1950. The victims were either forcibly arrested by the police or summoned to the police station, where they were detained or transferred to nearby detainment centers before being executed in August 1950.

The Commission recommended that the government officially apologize to the families of victims, support memorial services, revise family registries and other records, and provide peace and human rights education.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related Massacres in Yeongdeok, North Gyeongsang Province

editThe Commission determined that in July 1950, approximately 270 regional Bodo League members and those held in preventive detention were illegally victimized by the military and police forces in Yeongdeok County, North Gyeongsang Province. Shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War, the 23rd Regiment of the 3rd Army and Yeongdeok Police were concerned that Bodo League members might collaborate with the North Korean People's Army and conduct sabotage behind the front lines. In order to prevent this, the police and army executed them.

The Commission recommended an official apology, revision of family registries and other records, peace and human rights education, and financial support for memorial services.[citation needed]

Bodo League-related massacres in Busan and Sacheon

editThe Commission found that regional Bodo League members and those in preventive detention were killed by the Busan CIC, the military, and local police between July and September 1950. Bodo League members in the Busan and Sacheon regions were forcibly arrested or summoned to local police stations, where they were detained before being executed.

The Commission recommended that the government officially apologize to the families of the victims, support memorial services, revise family registries and other records, and provide peace and human rights education.[citation needed]

Survey to identify massacre victims

editA project was undertaken to conduct a survey of the number of civilian victims of the mass killings the took place during the Korean War, carried out in collaboration with outside research teams. In 2007, the Seokdang Research Institute at Dong-a University carried out a survey of civilian victims in the cities of Gimhae and Gongju, as well as rural areas in Jeolla, Chuncheong, Gyeongsang, and Gyeonggi provinces. The selected regions were chosen after an estimate of the scale and the representation of each mass killing. In particular, Ganghwa County, near Incheon, was included because it was on the military borderline between the two conflicting powers at the time. Gimhae was significant because a large number of mass killings against civilians occurred there, even though the region was never taken by the North.

In 2007, the investigative process was conducted on a total of 3,820 individuals, including bereaved family members and witnesses. As a result, some 8,600 victims were uncovered.

Categorized by region, there were found:

- 356 victims in Ganghwa County,

- 385 victims in Cheongwon County,

- 65 victims in Gongju,

- 373 victims in Yeocheon County,

- 517 victims in Cheongdo County,

- 283 victims in Gimhae,

- 1,880 victims in Gochang County,

- 2,818 victims in Youngam County, and

- 1,318 victims in Gurye County.

Divided by the type of victim, there were found:

- 1,457 leftist guerillas killed by the army or police forces of South Korea,

- 1,348 Bodo League members,

- 1,318 local leftist victims,

- 1,092 victims of the Yeosun Incident, and

- 892 victims accused of being collaborators of North Korea.[citation needed]

External relations

editCollaboration with truth-finding organizations and regional autonomous entities

editThe TRCK is an organization independent of any governmental or non-governmental political entities, and has sought to uncover the truth behind previously unknown or popularly misconceived historical incidents, thereby pursuing reconciliation between the victims and the perpetrators. It has sought to maintain cooperative relationships with regional governments and organizations, since its investigations cover a time period of nearly a century, and deal with areas throughout the Korean peninsula.

Collaboration with the government and other truth commissions

editThe TRCK is an organization established to discover the truth behind incidents in the past, and it has been crucial to call upon assistance from governmental authorities, such as the nation's police forces, the Ministry of Defense, and the National Intelligence Service. The TRCK held a monthly gathering with the heads of other truth-finding commissions and conducted meetings and seminars with various governmental organizations.

Through building a cooperative relationship among the organizations, the TRCK sought to increase efficiency in carrying out its work by exchanging relevant documents, sharing thoughts on the selection of research subjects, and adjudicating duplicated work.

The TRCK co-hosted a conference on the "Evaluation of Truth-finding Works and the Prospect Thereof" with the Presidential Commission on Suspicious Death in the Military, the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under the Japanese Imperialism, and the Presidential Committee for the Inspection of Collaborations for Japanese Imperialism. The concerned commissions shared various field experiences with respect to truth-finding work and exchanged ideas through various seminars and conferences.[citation needed]

Collaboration with regional organizations

editThe TRCK is authorized to delegate part of its work to local organizations or to cooperate with them. It relies on local organizations to solicit and gather petitions and to carry out on-the-ground research. The TRCK, together with 246 local organizations, led an awareness campaign soliciting petitions for a year starting on December 1, 2005. During this period, Song Ki-in, the first president of the TRCK, visited 16 different cities and numerous civic groups, and engaged in a media campaign to raise awareness of the significance of the TRCK's truth-finding work.[citation needed]

Collaboration with bereaved family members

editThe TRCK has the authority to hold conferences and consult with experts regarding its work. Especially in the case of investigations on Korea's independence movement and Korean communities abroad, the commission can carry out its investigation in collaboration with relevant research institutes or other agencies. In particular, since the organization representing family members of civilian victims killed during the Korean War accounts for a large portion of the petitions filed at the commission, close cooperation with this organization was essential.

The TRCK has been working to resolve any misunderstandings from more than 50 bereaved family unions. Additionally, the TRCK paid special attention to civic groups in order to collect diverse opinions and build an alliance to raise awareness and promote its mission through seminars and forums.[citation needed]

Future of truth-finding work in Korea

editSince the conservative Grand National Party (한나라당) came to power in Korea in February 2008, led by the new president Lee Myung-bak, some perceive that the commission's resources and mandate have become more vulnerable. Other commissions established during the term of former president Roh Moo-hyun have been targeted for cuts under the Lee government's policy of budget reduction.[citation needed]

In November, 2008, Shin Ji-ho, a lawmaker from the conservative Grand National Party, proposed a draft bill to merge multiple truth-finding commissions into one, the TRCK, a move which was met with strong resistance from progressives. On November 26, 2008,[17] American academic historian and author Bruce Cumings criticized the Lee's administration's handling of the textbook selection process in his interview with[18] The Hankyoreh daily.

The commission has been actively attempting to build an international alliance with countries that have similar historical experiences of civil wars and authoritarian dictatorships. Recently[when?], it signed a Memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Chile.

See also

edit- Bodo League massacre

- Chinilpa

- Ganghwa massacre

- Geochang massacre

- Goyang Geumjeong Cave Massacre

- Hà My massacre

- Jeju Uprising

- Mungyeong Massacre

- National Defense Corps Incident

- No Gun Ri Massacre

- Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất massacre

- Sancheong-Hamyang massacre

- Yeosu–Suncheon Rebellion

- Yongsan bombing

- Brothers Home

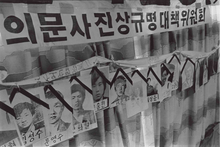

Gallery

edit-

Near Daejeon, South Korea, 1950

-

South Korean soldiers walk among some of the thousands of political prisoners shot at Daejeon, South Korea, 1950

References

edit- ^ Hanley, Charles J.; Jae-Soon Chang (August 3, 2008). "Seoul probes civilian 'massacres' by US". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (December 3, 2007). "Unearthing War's Horrors Years Later in South Korea". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J.; Jae-Soon Chang (August 3, 2008). "AP IMPACT: Seoul probes civilian 'massacres' by US". AP Impact. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ^ Framework Act on Clearing up Past Incidents for Truth and Reconciliation

- ^ Nurses, Miners (October 17, 2008). "Korea's Economic Growth Contributed by Dispatched Korean Nurses and Miners in Germany". The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (South Korea). Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ "[Editorial] We must properly understand and define the 1946 Daegu uprising". Hankyoreh. 2013-01-22. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ DongA Teugwi (October 30, 2008). "DongA Ilbo and the government are told to apologize for past civil rights violations". HanKyorye Daily. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ^ Hardy, Bert. "Political prisoners waiting for being loaded in trucks transferring them to their execution sites, Sept. 1, 1950". Picture Post.

- ^ Choe, Sang-hun (July 21, 2008). "Korean War survivors tell of carnage inflicted by U.S." International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ^ Donadio, Rachel. "IHT.com". IHT.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ In accommodating international norms, the American reinterpretation of the immunity of noncombatant placed some limits on the use of violence. One clear limit manifested itself in Americans' unwillingness to accept the idea that civilian populations themselves were legitimate targets in war. However, the limits on violence provided meager protection for civilians caught in the midst of the Korean War, and the reinterpretation of noncombatant immunity helped to justify violence as well. When Americans believed their armed forces did not intend to harm noncombatants and attacked only military targets, they remained more accepting of war's violence. Collateral damage became, to many, an unfortunate but acceptable cost of war., Collateral Damage; Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II, 2006, Routledge, Sahr Conway-Lanz

- ^ "PR Apologizes for Past Abuses of State Power". Korea Broadcasting System (KBS). January 24, 2008. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J.; Martha Mendoza (2006-05-29). "U.S. Policy Was to Shoot Korean Refugees". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J.; Martha Mendoza (2007-04-13). "Letter reveals U.S. intent at No Gun Ri". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ The Hankyoreh (June 25, 2007). "Waiting for the truth". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ The Hankyoreh (June 25, 2007). "Waiting for the truth". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce (November 27, 2008). "Lee administration is trying to 'bury all the new history we have learned'". The Hangyoreh Daily. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ^ "한겨레". The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 2019-06-06.