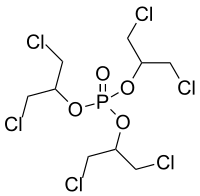

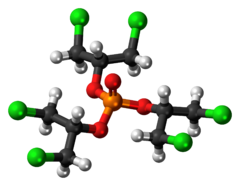

Tris(1,3-dichloroisopropyl)phosphate (TDCPP) is a chlorinated organophosphate. Organophosphate chemicals have a wide variety of applications and are used as flame retardants, pesticides, plasticizers, and nerve gases. TDCPP is structurally similar to several other organophosphate flame retardants, such as tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP) and tris(chloropropyl)phosphate (TCPP). TDCPP and these other chlorinated organophosphate flame retardants are all sometimes referred to as "chlorinated tris".

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Tris(1,3-dichloropropan-2-yl) phosphate | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.767 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H15Cl6O4P | |

| Molar mass | 430.89 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling:[1] | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H351 | |

| P201, P202, P281, P308+P313, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Manufacture

editTDCPP is produced by the reaction of epichlorohydrin with phosphorus oxychloride.

Uses

editFlame retardant

editUntil the late 1970s, TDCPP was used as a flame retardant in children’s pajamas in compliance with the U.S. Flammable Fabrics Act of 1953. This use was discontinued after children wearing fabrics treated with a very similar compound, tris(2,3-dibromopropyl) phosphate, were found to have mutagenic byproducts in their urine.[2]

Following the 2005 phase-out of PentaBDE in the United States, TDCPP became one of the primary flame retardants used in flexible polyurethane foam used in a wide variety of consumer products, including automobiles, upholstered furniture, and some baby products.[3][4][5][6] TDCPP can also be used in rigid polyurethane foam boards used for building insulation.[7] In 2011 it was reported that TDCPP was found in about a third of tested baby products.[8]

Some fabrics used in camping equipment are also treated with TDCPP to meet CPAI-84, a standard established by the Industrial Fabrics Association International to evaluate the flame resistance of fabrics and other materials used in tents.[9]

Current total production of TDCPP is not well known. In 1998, 2002, and 2006, production in the United States was estimated to be between 4,500 and 22,700 metric tons,[7] and thus TDCPP is classified as a high production volume chemical.

Presence in the environment

editTDCPP is an additive flame retardant, meaning that it is not chemically bonded to treated materials. Additive flame retardants are thought to be more likely to be released into the surrounding environment during the lifetime of the product than chemically bonded, or reactive, flame retardants.[7]

TDCPP degrades slowly in the environment and is not readily removed by waste water treatment processes.[7]

Indoors

editTDCPP has been detected in indoor dust, although concentrations vary widely. A study of house dust in the U.S. found that over 96% of samples collected between 2002 and 2007 contained TDCPP at an average concentration of over 1.8 ppm, while the highest was over 56 ppm.[5] TDCPP was also detected in 99% of dust samples collected in 2009 in the Boston area from offices, homes, and vehicles. The second study found an average concentration similar to that of the previous study but a greater range of concentrations: one sample collected from a vehicle contained over 300 ppm TDCPP in the dust.[3] Similar concentrations have been reported for dust samples collected in Europe and Japan.[10][11][12]

TDCPP has also been measured in indoor air samples. Its detection in air samples, however, is less frequent and generally at lower concentrations than other organophosphate flame retardants such as TCEP and TCPP, likely due to its lower vapor pressure.[7][13][14]

Outdoors

editAlthough TDCPP is generally found at the highest concentrations in enclosed environments, such as homes and vehicles, it is widespread in the environment. Diverse environmental samples, ranging from surface water to wildlife tissues, have been found to contain TDCPP.[7] The highest levels of contamination are generally near urban impacted areas; however, samples from even relatively remote reference sites have contained TDCPP.[15][16]

Human exposure

editHumans are thought to be exposed to TDCPP and other flame retardants through several routes, including inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact with treated materials. Rodent studies show that TDCPP is readily absorbed through the skin and gastrointestinal tract.[17][18] Infants and young children are expected to have the highest exposure to TDCPP and other indoor contaminants for several reasons. Compared to adults, children spend more time indoors and closer to the floor, where they are exposed to higher amounts of dust particles. In addition, they frequently put their hands and other objects into their mouths without washing.[19]

Several studies show that TDCPP can accumulate in human tissues. It has been detected in semen, fat, and breast milk,[20][21][22] and the metabolite bis (1,3-dichloropropyl) phosphate (BDCPP) has been detected in urine.[3][23][24]

Health effects

editAcute

editOrganophosphate toxicity is classically associated with acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme responsible for breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Many organophosphates, especially those designed to act as nerve agents or pesticides, bind with the active site on acetylcholinesterase, preventing it from breaking down acetylcholine.[25] In rodent studies, TDCPP was found to have very low capacity to inhibit acetylcholinesterase, and it is considered to have low acute toxicity.[26] Animals that were given very high doses (>1 g/kg/day) exhibited clinical signs of organophosphate poisoning, including muscle weakness, loss of coordination, hyperactivity, and death.[7]

Chronic

editCancer

editSeveral studies suggest that TDCPP may be carcinogenic. Rodents that were fed TDCPP over two years showed increased tumor formation in the liver and brain.[27] Metabolites of TDCPP were also determined to be mutagenic in bacteria using the Ames test.[2]

In 2011, TDCPP was listed as a carcinogen under California Proposition 65, a law that identifies and regulates chemicals determined by the California Environmental Protection Agency ‘to cause cancer, birth defects or other reproductive harm.’[28]

Reproduction

editMen living in homes with high concentrations of TDCPP in house dust were more likely to have decreased sperm counts and increased serum prolactin levels.[29] Women typically have higher concentrations of the hormone prolactin than men do. Release of prolactin is regulated by the neurotransmitter dopamine. Prolactin is important for regulating lactation, sex drive, and other hormones.

Development

editTDCPP and other similar organophosphate flame retardants have been found to disrupt normal development.

Chickens exposed to TDCPP as embryos developed abnormally: Exposure to 45 ug/g resulted in shorter head-to-bill lengths, decreased body weight, and smaller gallbladders, while 7.64 ug/g lowered free thyroxine (T4) levels in the blood.[30]

Similarly, zebrafish raised in water containing TDCPP died or developed severe malformations. When the TDCPP exposure began very early during embryogenesis, by the 2 cell stage, the developing embryos were more severely affected.[31][32][33]

TDCPP was found to affect several neurodevelopmental processes in a neuronal cell line. PC12 cells showed decreased cell replication and growth, increased oxidative stress, and altered cellular differentiation.[34] In a developing organism, these effects could change the way the brain cells communicate and function, resulting in permanent changes in nervous system function.[35]

Thyroid

editTDCPP exposure was found to alter mRNA expression of several genes that regulate thyroid function in zebrafish embryos and larvae.[36][37] Early life exposure also changed thyroid hormone levels in both zebrafish and chick embryos: triiodothyronine (T3) levels increased in exposed zebrafish while thyroxine (T4) levels decreased in both species.[30][37]

TDCPP may affect brain development and function via the thyroid system. Thyroid hormones are critical for normal growth and development and for proper function in the endocrine system. The developing brain in particular is highly sensitive to thyroid hormone disruptions. Disruptions to the thyroid system of either the mother or the fetus during early brain development are associated with lower IQ scores and increased risk for ADHD or other neurobehavioral disorders.[38][39]

References

edit- ^ "Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl)phosphate". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ a b Gold MD, Blum A, Ames BN (May 1978). "Another flame retardant, tris-(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl)-phosphate, and its expected metabolites are mutagens". Science. 200 (4343): 785–7. Bibcode:1978Sci...200..785G. doi:10.1126/science.347576. PMID 347576.

- ^ a b c Carignan CC, McClean MD, Cooper EM, Watkins DJ, Fraser AJ, Heiger-Bernays W, Stapleton HM, Webster TF (May 2013). "Predictors of tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate metabolite in the urine of office workers". Environment International. 55: 56–61. Bibcode:2013EnInt..55...56C. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2013.02.004. PMC 3666188. PMID 23523854.

- ^ Stapleton HM, Klosterhaus S, Eagle S, Fuh J, Meeker JD, Blum A, Webster TF (October 2009). "Detection of organophosphate flame retardants in furniture foam and U.S. house dust". Environmental Science & Technology. 43 (19): 7490–5. Bibcode:2009EnST...43.7490S. doi:10.1021/es9014019. PMC 2782704. PMID 19848166.

- ^ a b Stapleton HM, Klosterhaus S, Keller A, Ferguson PL, van Bergen S, Cooper E, Webster TF, Blum A (June 2011). "Identification of flame retardants in polyurethane foam collected from baby products". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (12): 5323–31. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.5323S. doi:10.1021/es2007462. PMC 3113369. PMID 21591615.

- ^ Stapleton HM, Sharma S, Getzinger G, Ferguson PL, Gabriel M, Webster TF, Blum A (December 2012). "Novel and high volume use flame retardants in US couches reflective of the 2005 PentaBDE phase out". Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (24): 13432–9. Bibcode:2012EnST...4613432S. doi:10.1021/es303471d. PMC 3525014. PMID 23186002.

- ^ a b c d e f g van der Veen I, de Boer J (August 2012). "Phosphorus flame retardants: properties, production, environmental occurrence, toxicity and analysis". Chemosphere. 88 (10): 1119–53. Bibcode:2012Chmsp..88.1119V. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.067. PMID 22537891.

- ^ Martin A (17 May 2011). "Chemical Suspected in Cancer Is in Baby Products". The New York Times.

- ^ Keller AS, Raju NP, Webster TF, Stapleton HM (February 2014). "Flame Retardant Applications in Camping Tents and Potential Exposure". Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 1 (2): 152–155. Bibcode:2014EnSTL...1..152K. doi:10.1021/ez400185y. PMC 3958138. PMID 24804279.

- ^ Bergh C, Torgrip R, Emenius G, Ostman C (February 2011). "Organophosphate and phthalate esters in air and settled dust - a multi-location indoor study". Indoor Air. 21 (1): 67–76. Bibcode:2011InAir..21...67B. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2010.00684.x. PMID 21054550.

- ^ Kanazawa A, Saito I, Araki A, Takeda M, Ma M, Saijo Y, Kishi R (February 2010). "Association between indoor exposure to semi-volatile organic compounds and building-related symptoms among the occupants of residential dwellings". Indoor Air. 20 (1): 72–84. Bibcode:2010InAir..20...72K. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00629.x. hdl:2115/87324. PMID 20028434.

- ^ Marklund A, Andersson B, Haglund P (December 2003). "Screening of organophosphorus compounds and their distribution in various indoor environments". Chemosphere. 53 (9): 1137–46. Bibcode:2003Chmsp..53.1137M. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00666-0. PMID 14512118.

- ^ Marklund A, Andersson B, Haglund P (October 2005). "Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in Swedish sewage treatment plants". Environmental Science & Technology. 39 (19): 7423–9. Bibcode:2005EnST...39.7423M. doi:10.1021/es051013l. PMID 16245811.

- ^ Staaf T, Ostman C (September 2005). "Organophosphate triesters in indoor environments". Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 7 (9): 883–7. doi:10.1039/b506631j. PMID 16121268.

- ^ Andresen JA, Grundmann A, Bester K (October 2004). "Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticisers in surface waters". The Science of the Total Environment. 332 (1–3): 155–66. Bibcode:2004ScTEn.332..155A. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.021. PMID 15336899.

- ^ Regnery J, Püttmann W (February 2010). "Seasonal fluctuations of organophosphate concentrations in precipitation and storm water runoff". Chemosphere. 78 (8): 958–64. Bibcode:2010Chmsp..78..958R. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.027. PMID 20074776.

- ^ Minegishi KI, Kurebayashi H, Nambaru S, Morimoto L, Takahashi T, Yamaha T (1988). "Comparative studies on absorption, distribution, and excretion of flame retardants halogenated alkyl phosphate in rats". Eisei Kagaku. 34 (2): 102–114. doi:10.1248/jhs1956.34.102.

- ^ Nomeir AA, Kato S, Matthews HB (March 1981). "The metabolism and disposition of tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (Fyrol FR-2) in the rat". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 57 (3): 401–13. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(81)90238-6. PMID 7222047.

- ^ Child-specific exposure factors handbook. United States Environmental Protection Agency. September 2008.

- ^ Hudec T, Thean J, Kuehl D, Dougherty RC (February 1981). "Tris(dichloropropyl)phosphate, a mutagenic flame retardant: frequent cocurrence in human seminal plasma". Science. 211 (4485): 951–2. Bibcode:1981Sci...211..951H. doi:10.1126/science.7466368. PMID 7466368.

- ^ LeBel GL, Williams DT, Berard D (August 1989). "Triaryl/alkyl phosphate residues in human adipose autopsy samples from six Ontario municipalities". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 43 (2): 225–30. Bibcode:1989BuECT..43..225L. doi:10.1007/BF01701752. PMID 2775890. S2CID 30730887.

- ^ Sundkvist AM, Olofsson U, Haglund P (April 2010). "Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers in marine and fresh water biota and in human milk". Journal of Environmental Monitoring. 12 (4): 943–51. doi:10.1039/b921910b. PMID 20383376.

- ^ Cooper EM, Covaci A, van Nuijs AL, Webster TF, Stapleton HM (October 2011). "Analysis of the flame retardant metabolites bis(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (BDCPP) and diphenyl phosphate (DPP) in urine using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 401 (7): 2123–32. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-5294-7. PMC 3718013. PMID 21830137.

- ^ Meeker JD, Cooper EM, Stapleton HM, Hauser R (May 2013). "Urinary metabolites of organophosphate flame retardants: temporal variability and correlations with house dust concentrations". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (5): 580–5. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205907. PMC 3673195. PMID 23461877.

- ^ Eaton DL, Daroff RB, Autrup H, Bridges J, Buffler P, Costa LG, Coyle J, McKhann G, Mobley WC, Nadel L, Neubert D, Schulte-Hermann R, Spencer PS (2008). "Review of the toxicology of chlorpyrifos with an emphasis on human exposure and neurodevelopment". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 38 Suppl 2 (s2): 1–125. doi:10.1080/10408440802272158. PMID 18726789. S2CID 84162223.

- ^ Eldefrawi AT, Mansour NA, Brattsten LB, Ahrens VD, Lisk DJ (June 1977). "Further toxicologic studies with commercial and candidate flame retardant chemicals. Part II". Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 17 (6): 720–6. Bibcode:1977BuECT..17..720E. doi:10.1007/BF01685960. PMID 880389. S2CID 31364047.

- ^ Freudenthal RI, Henrich RT (2000). "Chronic toxicity and carcinogenic potential of tris-(1, 3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate in Sprague-Dawley rat". International Journal of Toxicology. 19 (13674): 119–125. doi:10.1080/109158100224926. S2CID 93824913.

- ^ "Proposition 65 in Plain Language!". California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. 2013. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ^ Meeker JD, Stapleton HM (March 2010). "House dust concentrations of organophosphate flame retardants in relation to hormone levels and semen quality parameters". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (3): 318–23. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901332. PMC 2854757. PMID 20194068.

- ^ a b Farhat A, Crump D, Chiu S, Williams KL, Letcher RJ, Gauthier LT, Kennedy SW (July 2013). "In Ovo effects of two organophosphate flame retardants--TCPP and TDCPP--on pipping success, development, mRNA expression, and thyroid hormone levels in chicken embryos". Toxicological Sciences. 134 (1): 92–102. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kft100. PMID 23629516.

- ^ McGee SP, Cooper EM, Stapleton HM, Volz DC (November 2012). "Early zebrafish embryogenesis is susceptible to developmental TDCPP exposure". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (11): 1585–91. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205316. PMC 3556627. PMID 23017583.

- ^ Dasgupta S, Cheng V, Vliet SM, Mitchell CA, Volz DC (September 2018). "Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) Phosphate Exposure During the Early-Blastula Stage Alters the Normal Trajectory of Zebrafish Embryogenesis". Environmental Science & Technology. 52 (18): 10820–10828. Bibcode:2018EnST...5210820D. doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b03730. PMC 6169527. PMID 30157643.

- ^ Dasgupta S, Vliet SM, Kupsco A, Leet JK, Altomare D, Volz DC (2017-12-14). "Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate disrupts dorsoventral patterning in zebrafish embryos". PeerJ. 5: e4156. doi:10.7717/peerj.4156. PMC 5733366. PMID 29259843.

- ^ Dishaw LV, Powers CM, Ryde IT, Roberts SC, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, Stapleton HM (November 2011). "Is the PentaBDE replacement, tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCPP), a developmental neurotoxicant? Studies in PC12 cells". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 256 (3): 281–9. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2011.01.005. PMC 3089808. PMID 21255595.

- ^ Bondy SC, Campbell A (September 2005). "Developmental neurotoxicology" (PDF). Journal of Neuroscience Research. 81 (5): 605–12. doi:10.1002/jnr.20589. PMID 16035107. S2CID 39938045.

- ^ Liu X, Ji K, Choi K (June 2012). "Endocrine disruption potentials of organophosphate flame retardants and related mechanisms in H295R and MVLN cell lines and in zebrafish". Aquatic Toxicology. 114–115: 173–81. Bibcode:2012AqTox.114..173L. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.02.019. PMID 22446829.

- ^ a b Wang Q, Liang K, Liu J, Yang L, Guo Y, Liu C, Zhou B (January 2013). "Exposure of zebrafish embryos/larvae to TDCPP alters concentrations of thyroid hormones and transcriptions of genes involved in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis". Aquatic Toxicology. 126: 207–13. Bibcode:2013AqTox.126..207W. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.11.009. PMID 23220413.

- ^ Gilbert ME, Rovet J, Chen Z, Koibuchi N (August 2012). "Developmental thyroid hormone disruption: prevalence, environmental contaminants and neurodevelopmental consequences". Neurotoxicology. 33 (4): 842–52. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2011.11.005. PMID 22138353.

- ^ Zoeller TR, Dowling AL, Herzig CT, Iannacone EA, Gauger KJ, Bansal R (June 2002). "Thyroid hormone, brain development, and the environment". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 Suppl 3 (April): 355–61. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110s3355. PMC 1241183. PMID 12060829.