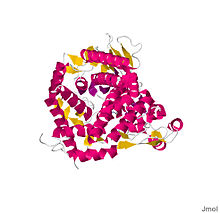

The enzyme Trehalase is a glycoside hydrolase, produced by cells in the brush border of the small intestine, which catalyzes the conversion of trehalose to glucose.[2][3][4][5] It is found in most animals.

| trehalase (brush-border membrane glycoprotein) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Trehalase [1] | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Symbol | TREH | ||||||

| NCBI gene | 11181 | ||||||

| HGNC | 12266 | ||||||

| OMIM | 275360 | ||||||

| RefSeq | NM_007180 | ||||||

| UniProt | O43280 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| EC number | 3.2.1.28 | ||||||

| Locus | Chr. 11 q23.3 | ||||||

| |||||||

The non-reducing disaccharide trehalose (α-D-glucopyranosyl-1,1-α-D-glucopyranoside) is one of the most important storage carbohydrates, and is produced by almost all forms of life except mammals. The disaccharide is hydrolyzed into two molecules of glucose by the enzyme trehalase. There are two types of trehalases found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, viz. neutral trehalase (NT) and acid trehalase (AT) classified according to their pH optima [4]. NT has an optimum pH of 7.0, while that of AT is 4.5.

Recently it has been reported that more than 90% of total AT activity in S. cerevisiae is extracellular and cleaves extracellular trehalose into glucose in the periplasmic space.

Trehalose hydrolysis

editOne molecule of trehalose is hydrolyzed to two molecules of glucose by the enzyme trehalase. Enzymatic hydrolysis of trehalose was first observed in Aspergillus niger by Bourquelot in 1893. Fischer reported this reaction in S. cerevisiae in 1895. Since then the trehalose hydrolyzing enzyme, trehalase (α, α-trehalose-1-C-glucohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.28) has been reported from many other organisms including plants and animals.[6] Though trehalose is not known to be produced by mammals, trehalase enzyme is found to be present in the kidney brush border membrane and the intestinal villi membranes. In the intestine the function of this enzyme is to hydrolyze ingested trehalose. Individuals with a defect in their intestinal trehalase have diarrhea when they eat foods with high trehalose content, such as mushrooms.[6] Trehalose hydrolysis by trehalase enzyme is an important physiological process for various organisms, such as fungal spore germination, insect flight, and the resumption of growth in resting cells.[6]

Bacterial trehalase

editTrehalose has been reported to be present as a storage carbohydrate in Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Rhizobium and in several actinomycetes and may be partially responsible for their resistance properties. Most of the trehalase enzymes isolated from bacteria have as optimum pH of 6.5–7.5. The trehalase enzyme of Mycobacterium smegmatis is a membrane bound protein. Periplasmic trehalase of Escherichia coli K12 is induced by growth at high osmolarity. The hydrolysis of trehalose into glucose takes place in the periplasm, and the glucose is then transported into the bacterial cell. Another cytoplasmic trehalase has also been reported from E. coli. The gene, which encodes this cytoplasmic trehalase, exhibits high homology to the periplasmic trehalase.

Trehalase in plants

editIn plant kingdom, though trehalose has been reported from several pteridophytes including Selaginella lepidophylla and Botrychium lunaria; the sugar is rare in vascular plants and reported only in ripening fruits of several members of Apiaceae and in the leaves of the desiccation-tolerant angiosperm Myrothamnus flabellifolius. But, the enzyme trehalase is ubiquitous in plants. This is puzzling that trehalase is present in higher plants, though its substrate is absent. No clear role has been demonstrated for trehalase activity in plants. However, trehalose inhibits the synthesis of its precursor, trehalose 6-phosphate, a plant metabolism regulator;[7] hence, its removal may be required.[8] It has been suggested that trehalases could play a role in defense mechanisms or the enzyme could play a role in the degradation of trehalose derived from plant-associated microorganisms.

Fungal trehalase

editTwo distinct trehalases have been reported from S. cerevisiae. One is regulated by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation and localized to the cytosol. The second trehalase activity is found in the vacuoles. The pH optimum of cytosolic trehalse was determined to be approximately 7.0 and is thus referred to as 'neutral trehalase' (NT); whereas the vacuolar trehalase is most active at pH 4.5 and consequently termed 'acid trehalase' (AT). These enzymes are encoded by two different genes – NTH1 and ATH1 respectively.

Neutral trehalase

editThe cytosolic trehalase enzyme, NT, has been purified and characterized extensively from S. cerevisiae. In non-denaturing gels this enzyme protein exhibited a molecular mass of 160 kDa, while in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) it showed a mass of 80 kDa. This hydrolase enzyme is specific for trehalose. The Km of NT has been reported to be 5.7 mM. The gene responsible for trehalase activity in S. cerevisiae is NTH1. This gene is with an open reading frame of 2079 base pairs (bp), encoding a protein of 693 amino acids, corresponding to a molecular mass of 79569 Da.

NT activity is regulated by protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Phosphorylation with cAMP-dependent protein kinase activates NT. Dephosphorylation of the purified phosphorylated enzyme by alkaline phosphatase caused an almost complete inactivation of the enzyme activity; but a recovery of the enzyme activity could be observed by rephosphorylation while incubating with ATP and protein kinase. The activity of NT in crude extracts is enhanced by polycations, while the activity of purified phosphorylated NT is inhibited by them. The activation of crude extracts was found to be due to the removal of polyphosphates, both of which inhibit NT activity.

Acid Trehalase

editThe molecular weight of AT was found to be 218 kDa by gel filtration chromatography. AT is a glycoprotein. It has 86% carbohydrate content. It has been reported that the maturation of AT is a stepwise process beginning with a carbohydrate-free 41 kDa protein; this form is then core-glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum to form a 76 kDa glycol-protein. In Golgi bodies, the protein is further glycosylated yielding a 180 kDa form, which ultimately attains a maturity in vacuoles, where its molecular weight becomes around 220 kDa. The 41 kDa carbohydrate free protein moiety of the enzyme was obtained by Endoglycosidase H treatment of purified AT, resulted after sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis27. AT exhibited an apparent Km for trehalose of about 4.7 mM at pH 4.5. The gene responsible for AT activity in S. cerevisiae is ATH1.

Ath1p, i.e. AT, has been reported to be necessary for S. cerevisiae to utilize extracellular trehalose as carbon source16. ATH1 deletion mutant of the yeast could not grow in the medium with trehalose as the carbon source.

Researchers have suggested that AT moves from its site of synthesis to the periplasmic space, where it binds exogenous trehalose to internalize it and hydrolyze it in the vacuoles. Recently it has been shown that more than 90% of AT activity in S. cerevisiae is extracellular and the hydrolysis of trehalose into glucose takes place at the periplasmic space. Previously, a highly glycosylated protein, gp37, which is the product of YGP1 gene, was reported to be co-purified with AT activity. Invertase activity was also reported to be co-purified with AT activity. The physical association of AT with these two proteins was thought to suffice for the AT to be secreted by invertase and gp37 secretion pathways in absence of any known secretion signal for Ath1p.

In a Candida utils strain, one regulatory a one non-regulatory trehalase were also reported. These two enzymes were reported to be distinguishable by their molecular weight, behavior in ion-exchange chromatography and kinetic properties. The regulatory trehalase appeared to be a cytoplasmic enzyme and the nonregulatory enzyme was mostly detected in vacuoles. But, in a more recent report, a C. utils strain was demonstrated to lack any detectable AT activity but contain only NT activity. AT activity was not detectable in this strain, though the strain was shown to utilize extracellular trehalose as carbon source.

References

edit- ^ Gibson RP, Gloster TM, Roberts S, Warren RA, Storch de Gracia I, García A, et al. (2007). "Molecular basis for trehalase inhibition revealed by the structure of trehalase in complex with potent inhibitors". Angewandte Chemie. 46 (22): 4115–9. doi:10.1002/anie.200604825. PMID 17455176.

- ^ Myrbäck K, Örtenblad B (1937). "Trehalose und Hefe. II. Trehalasewirkung von Hefepräparaten". Biochem. Z. 291: 61–69.

- ^ Kalf GF, Rieder SV (February 1958). "The purification and properties of trehalase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 230 (2): 691–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)70491-2. PMID 13525386.

- ^ Hehre EJ, Sawai T, Brewer CF, Nakano M, Kanda T (June 1982). "Trehalase: stereocomplementary hydrolytic and glucosyl transfer reactions with alpha- and beta-D-glucosyl fluoride". Biochemistry. 21 (13): 3090–7. doi:10.1021/bi00256a009. PMID 7104311.

- ^ Mori H, Lee JH, Okuyama M, Nishimoto M, Ohguchi M, Kim D, et al. (November 2009). "Catalytic reaction mechanism based on alpha-secondary deuterium isotope effects in hydrolysis of trehalose by European honeybee trehalase". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 73 (11): 2466–73. doi:10.1271/bbb.90447. PMID 19897915. S2CID 22774772.

- ^ a b c Elbein AD, Pan YT, Pastuszak I, Carroll D (April 2003). "New insights on trehalose: a multifunctional molecule". Glycobiology. 13 (4): 17R – 27R. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwg047. PMID 12626396.

- ^ Paul MJ, Primavesi LF, Jhurreea D, Zhang Y (2008). "Trehalose metabolism and signaling". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 59: 417–41. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092945. PMID 18257709.

- ^ Loewus FA, Tanner W, eds. (December 2012). Plant carbohydrates I: Intracellular carbohydrates. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 274. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-68275-9_7. ISBN 978-3-642-68277-3.