This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

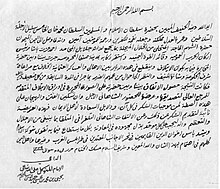

The Treaty of Daan (or Da'an) (Arabic: صلح دعان) was an agreement signed in October 1911 at Daan in the Yemen Vilayet by a representative of the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and Imam Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, the Zaydi Imam of Yemen expanding autonomy in the areas of the Ottoman province inhabited by the Zaydis, and ending the Yemeni–Ottoman conflicts.[1][2]

Background

editRelations between the Ottomans and the imams of the Zaydis had long been conflictual. Angered by the misrule of the Ottoman officials, the imams, who were treated merely as local religious leaders by the Turks who denied them the right to temporal rule, looked back to their historical claim over greater Yemen for inspiration. This was further stimulated by the Zaydi political concept, by which they were encouraged to rise up as imams against an unjust ruler as part of their religious duty, hence the periodic uprisings against the Ottomans. [3]

Negotiations

editSecret negotiations were initiated in June 1911 between Imam Yahya, the spiritual and temporal leader of the Zaydi branch of Shi'a Islam who has been leading periodic uprisings against Ottoman rule in the highlands of Yemen since 1905, and Ahmed Izzet Pasha, the new Ottoman wali and commander-in-chief of Yemen.

In the years when he had been chief of the Ottoman general staff, Izzet Pasha had proposed as a solution to the costly military stalemate in Yemen that the mountainous regions inhabited by the Zaydis be left to their effective control while Turkey would retain the coastal regions, the Tihamah, leaving only a token garrison in Sanaa. It is on this basis that the negotiations were conducted and in September a compromise was reached. The treaty was signed by both parties at a place called Daan north of Amran on 18 October 1911. The terms of the settlement were apparently accepted in principle by the cabinet in Constantinople and the treaty was ratified in 1913. The Ottoman decision to sign a treaty has also been in response to the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War, when Tripoli was attacked by the Italians in September 1911, the Turks being aware that they would be unable to send troops simultaneously to both Yemen and Tripoli. [4]

Treaty provisions

editThe Ottomans agreed to support Imam Yahya against all possible rivals to the imamate in the future, to permit him to reside in Kawkaban and to grant him an annual subsidy of 25,000 Turkish pounds from the revenues of the province. Key Zaydi sheiks were also granted subsidies. Ottoman civil law would be totally abrogated and replaced by Islamic Law in the seven highland districts of Amran, Kawkaban, Dhamar, Yarim, Ibb, Hajjah and Hajjur. Islamic law in those districts would be administered under the imam, who would nominate the qadis in those districts, subject to the approval of the central government.[5]

For his part, Iman Yahya — whose uprising of 1911 had almost collapsed by the end of April due to lack of support from tribesmen from a number of agricultural districts — agreed to renounce his claim to the caliphate and drop the title of 'Commander of the Faithful' assumed by his predecessors and himself, and to style himself simply as 'Imam of the Zaydis'. He also renounced to collect zakat in the areas that were to remain under Ottoman jurisdiction. [6]

Outcome

editThe Treaty of Daan marked a turning point in the history of Yemeni uprisings since the Turkish occupation of Sanaa in 1872. It eliminated the main sources of friction and discord between them and the Imam.

References

edit- ^ Kamil A. Mahdi, et al., Yemen into the Twenty-first Century: Continuity and Change (Garnet & Ithaca Press, 2007) p100

- ^ Robert Burrowes, Historical Dictionary of Yemen (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1995), xxvi.

- ^ Abdol Rauh Yaccob, "Yemeni opposition to Ottoman rule: an overview", Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, volume 42, July 2011 (2012), p. 418.

- ^ Yaccob (2011), p. 416, 418.

- ^ Yaccob (2011), p. 417.

- ^ Yaccob (2011), p. 417.