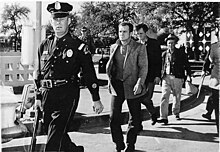

The three tramps are three men photographed by several Dallas-area newspapers under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. Since the mid-1960s, various allegations have been made about the identities of the men and their involvement in a conspiracy to kill Kennedy. The three men were later identified from Dallas Police Department records as Gus Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John Gedney.

Early allegations

editThe Dallas Morning News, the Dallas Times Herald, and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram photographed three transients under police escort near the Texas School Book Depository shortly after the assassination.[1] The men later became known as the "three tramps".[2] According to Vincent Bugliosi, allegations that these men were involved in a conspiracy originated from theorist Richard E. Sprague who compiled the photographs in 1966 and 1967, and subsequently turned them over to Jim Garrison during his investigation of Clay Shaw.[2] Appearing before a nationwide audience on the January 31, 1968, episode of The Tonight Show, Garrison held up a photo of the three and suggested they were involved in the assassination.[2]

Later allegations: E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis

editLater, in 1974, assassination researchers Alan J. Weberman and Michael Canfield compared photographs of the men to people they believed to be suspects involved in a conspiracy and said that two of the men were Watergate burglars E. Howard Hunt and Frank Sturgis.[3] Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory helped bring national media attention to the allegations against Hunt and Sturgis in 1975 after obtaining the comparison photographs from Weberman and Canfield.[3] Immediately after obtaining the photographs, Gregory held a press conference that received considerable coverage and his charges were reported in Rolling Stone and Newsweek.[3][4]

The Rockefeller Commission reported in 1975 that they investigated the allegation that Hunt and Sturgis, on behalf of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), participated in the assassination of Kennedy.[5] The final report of that commission stated that witnesses who testified that the "derelicts" bore a resemblance to Hunt or Sturgis, "were not shown to have any qualification in photo identification beyond that possessed by an average layman".[6] Their report also stated that FBI Agent Lyndal L. Shaneyfelt, "a nationally-recognized expert in photoidentification and photoanalysis" with the FBI photographic laboratory, had concluded from photo comparison that none of the men were Hunt or Sturgis.[7]

In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations reported that forensic anthropologists had again analyzed and compared the photographs of the "tramps" with those of Hunt and Sturgis, as well as with photographs of Thomas Vallee, Daniel Carswell, and Fred Lee Crisman.[8] According to the Committee, only Crisman resembled any of the tramps; but the same Committee determined that he was not in Dealey Plaza on the day of the assassination.[8]

According to Mark Lane, Sturgis became involved with Marita Lorenz in 1985, who later identified Sturgis as a gunman in the assassination.[9]

Other allegations: Charles Harrelson, Charles Rogers, and Chauncey Holt

editIn September 1982, contract killer Charles Harrelson, while wanted for the murder of federal judge John H. Wood Jr., "confessed" to killing Wood and President Kennedy, during a six-hour standoff with police in which he was reportedly high on cocaine.[10][11] Joseph Chagra, the brother of Jamiel Chagra, testified during Harrelson's trial that Harrelson claimed to have shot Kennedy and drew maps to show where he was hiding during the assassination.[12] Chagra said that he did not believe Harrelson's claim, and the AP reported that the FBI "apparently discounted any involvement by Harrelson in the Kennedy assassination".[12]

According to Jim Marrs's 1989 book Crossfire, Harrelson is believed to be the youngest and tallest of the "tramps" by many assassination researchers.[13] Marrs stated that Harrelson was involved "with criminals connected to intelligence agencies and the military"[14] and suggested that he was connected to Jack Ruby through Russell Douglas Matthews, a third party with links to organized crime who was known to both Harrelson and Ruby.[14]

In September 1991, private investigators John Craig and Philip Rogers, who were working on a book about an unsolved murder case, claimed that Charles Rogers, who disappeared in 1965 after the dismembered bodies of his parents were found in a refrigerator, was a CIA operative who was identified by his friends and relatives as one of the "tramps".[15] According to the Houston Chronicle, a homicide detective who worked on the original murder case of Rogers's parents described the scenario as "far-fetched".[15]

Three months later, in a 1991 Newsweek article about Oliver Stone's JFK, Chauncey Holt received national attention for various claims that he made regarding the assassination of President Kennedy, including that he was one of three CIA operatives photographed as the "tramps".[16][17][18] Holt stated that he was with Harrelson in Dealey Plaza on the day of the assassination.[19] According to Holt, he was ordered to Dallas to deliver phony Secret Service credentials, but was not involved in killing Kennedy nor did he have knowledge of who did.[16][17]

John Craig and Philip Rogers's 1992 book The Man on the Grassy Knoll eventually connected Charles Harrelson, Charles Rogers, and Chauncey Holt by alleging that they were the three tramps photographed in Dealey Plaza.[20] According to that book, Harrelson and Rogers were sharpshooters on the grassy knoll who were assisted by Holt.[20]

Historical explanation: Gus Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John Gedney

editIn 1992, journalist Mary La Fontaine discovered November 22, 1963 arrest records the Dallas Police Department had released in 1989, which named the three men as Gus W. Abrams, Harold Doyle, and John F. Gedney.[21] According to the arrest reports, the three men were "taken off a boxcar in the railroad yards right after President Kennedy was shot", detained as "investigative prisoners", described as unemployed and passing through Dallas, then released four days later.[21]

An immediate search for the three men by the FBI and others was prompted by an article by Ray and Mary La Fontaine on the front page of the February 9, 1992, Houston Post.[21] Less than a month later, the FBI reported that Abrams was dead and that interviews with Gedney and Doyle revealed no new information about the assassination.[22] According to Doyle, the three men had spent the night before the assassination in a local homeless shelter where they showered and ate before heading back to the railyard.[21]

Interviewed by A Current Affair in 1992, Doyle said that he was aware of the allegations and did not come forward for fear of being implicated in the assassination.[21] He added: "I am a plain guy, a simple country boy, and that's the way I want to stay. I wouldn't be a celebrity for $10 million."[21] Gedney independently affirmed Doyle's account,[21] and a researcher who tracked down Abrams' sister confirmed that Abrams lived the life of an itinerant train hopper and had died in 1987.[23]

Despite the Dallas Police Department's 1989 identifications of the three tramps as being Doyle, Gedney and Abrams and the lack of evidence connecting them to the assassination, some researchers have continued to maintain other identifications for the tramps and to theorize that they may have been connected to the crime.[24] Photographs of the three at the time of their arrest have fueled speculation as to their identities as they appeared to be well-dressed and clean-shaven, unusual for rail riders. Some researchers also thought it suspicious that the Dallas police had quickly released the tramps from custody, apparently without investigating whether they might have witnessed anything significant related to the assassination,[a] and that Dallas police claimed to have lost the records of their arrests[26][better source needed] as well as their mugshots and fingerprints.[27]

See also

editFurther reading

edit- Hedegaarde, Erik (5 April 2007). "The Last Confession of E. Howard Hunt". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 930. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi 2007, p. 930.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi 2007, p. 931.

- ^ Weberman, Alan J; Canfield, Michael (1992) [1975]. Coup D'Etat in America: The CIA and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy (Revised ed.). San Francisco: Quick American Archives. p. 7. ISBN 9780932551108.

- ^ "Chapter 19: Allegations Concerning the Assassination of President Kennedy". Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. June 1975. p. 251.

- ^ Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States, Chapter 19 1975, p. 256.

- ^ Report to the President by Commission on CIA Activities in the United States, Chapter 19 1975, p. 257.

- ^ a b "I.B. Scientific acoustical evidence establishes a high probability that two gunmen fired at President John F. Kennedy. Other scientific evidence does not preclude the possibility of two gunmen firing at the President. Scientific evidence negates some specific conspiracy allegations". Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations of the U.S. House of Representatives. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1979. pp. 91–92.

- ^ Lane, Mark. Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK? (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press 1992), pp. 294-97, pp. 298-303. ISBN 1-56025-048-8

- ^ Cartwright, Gary (September 1982). Curtis, Gregory (ed.). "The Man Who Killed Judge Wood". Texas Monthly. 10 (9). Austin, Texas: Texas Monthly, Inc.: 250. ISSN 0148-7736. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ^ Marrs, Jim (1989). Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-88184-648-5.

- ^ a b Jorden, Jay (November 22, 1982). "Kennedy controversy still goes on". The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. AP. p. 7. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ^ Marrs 1989, p. 333.

- ^ a b Marrs 1989, p. 335.

- ^ a b Hanson, Eric (September 28, 1991). "'65 case tied to JFK death?/Book will claim suspect in CIA". Houston Chronicle. Houston, Texas. p. A29. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ a b Alvord, Valerie (July 5, 1997). "Chauncey Holt; claimed inside scoop in JFK killing". The San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego. p. B.7.1.6.

- ^ a b Gates, David (December 23, 1991). "Bottom Line: How Crazy Is It?". Newsweek. 118: 52–54.

- ^ Presentation by Mary Holt at the November In Dallas Research Conference 2000.[1]

- ^ Kroth, Jerome A. (2003). Conspiracy in Camelot: The Complete History of the Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Algora Publishing. p. 1012. ISBN 0-87586-247-0.

- ^ a b Kroth 2003, pp. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bugliosi 2007, p. 933.

- ^ Bolt, John A. (March 3, 1992). "FBI queries hobos seized day JFK shot". Houston Chronicle. Houston, Texas. AP. p. A9. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ^ Bugliosi 2007, p. 934.

- ^ Fetzer, James H. Assassination Science : Experts Speak Out on the Death of JFK (Open Court, 1998). ISBN 0-8126-9366-3

- ^ Hurt, Henry (1986). Reasonable Doubt: An Investigation into the Assassination of John F. Kennedy. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 121. ISBN 0-03-004059-0.

- ^ Ray and Mary La Fontaine, The Fourth Tramp, Washington Post, 8/94.

- ^ Groden, Robert J., The Killing of a President, Studio, 1994. ISBN 0-14-024003-9.