Three Lives (1909) is a work of fiction written in 1905 and 1906 by American writer Gertrude Stein. [1] The book is separated into three stories, "The Good Anna," "Melanctha," and "The Gentle Lena."

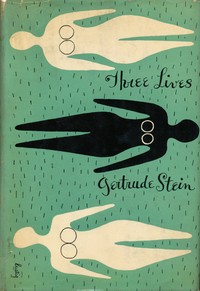

1941 edition (publ. New Directions) | |

| Author | Gertrude Stein |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Alvin Lustig (pictured) |

| Language | English |

Publication date | 30 July 1909 |

| Publication place | United States |

| OCLC | 177801689 |

| LC Class | PS3537.T323 T5 2007 |

The three stories are independent of each other, but all are set in Bridgepoint, a fictional town based on Baltimore.

Synopses

edit"donc je suis un malheureux et ce n’est ni ma faute ni celle de la vie"

"therefore, I am unhappy and this is neither my fault nor that of my life"— Jules Laforgue, quoted as epigraph to Three Lives[2]

Each of the three tales in Three Lives tells of a working-class woman living in Baltimore.[3]

"The Good Anna"

edit"The Good Anna," the first of Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives, is a novella set in "Bridgepoint" about Anna Federner, a servant of "solid lower middle-class south german stock."

Part I describes Anna’s happy life as housekeeper for Miss Mathilda and her difficulties with unreliable under servants and "stray dogs and cats". She loves her "regular dogs": Baby, an old, blind, terrier; "bad Peter," loud and cowardly; and "the fluffy little Rags." Anna is the undisputed authority in the household, and in her five years with Miss Mathilda she oversees in turn four under servants: Lizzie, Molly, Katy, and Sallie. Sometimes even the lazy and benign Miss Mathilda feels rebellious under Anna’s iron hand; she is also concerned because Anna is always giving away money, and tries to protect her from her many poor friends.

Part II, "The Life of the Good Anna", fills in the background. Born in Germany, in her teens Anna emigrates to "the far South", where her mother dies of consumption. She moves to Bridgepoint near her brother, a baker, and takes charge of the household of Miss Mary Wadsmith and her young nephew and niece, who are orphans. Little Jane resists Anna’s strong will, but after Anna has provoked a showdown becomes "careful and respectful" and even gives Anna a green parrot. When after six years Jane is finally married, Anna refuses to follow Miss Mary in the new household. Mrs. Lehntman, a widow and midwife who "was the romance of Anna’s life", helps Anna tell Miss Wadsmith that she cannot accompany her. Anna then goes to work for Doctor Shonjen, a hearty bachelor, with whom she gets along. Previously Shonjen has operated on her, and Anna’s general health remains poor: she has headaches and is "thin and worn". When Mrs. Lehntman, who has two careless children, adopts a baby without consulting Anna, the latter is offended and spends more time with another large working family, the Drehtens. She also visits her brother the baker, but has trouble with her sister-in-law, though she eventually helps with her savings when her god-daughter niece is married. Mrs. Lehntman rashly decides to open a boarding house, and Anna despite her misgivings lends her the necessary money, for "Romance is the ideal in one’s life and it is very lonely living with it lost". Having been once defeated in the matter of Johnny's adoption, she can no longer impose her will in the relationship. ("In friendship, power always has its downward curve.") When Dr. Shonjen marries a "proud" and "unpleasant" woman, Anna seeks a new position. Encouraged by a fortune-teller, she goes to work for Miss Mathilda, and these are her happiest years, until finally her ailing favorite dog Baby dies and Miss Mathilda leaves permanently for Europe.

Part III, "The Death of the Good Anna," chronicles her last years. Anna continues to live in the house Miss Mathilda has left her and takes in boarders, but charges too little to make ends meet and has to dismiss her help Sallie. She is still happy with her customers and her dogs, but works too much and weakens. Mrs. Drehten, her only remaining friend, convinces her to be operated. "Then they did the operation, and then the good Anna with her strong, strained, worn-out body died". Mrs. Drehten writes the news to Miss Mathilda.

The story is written in Stein’s straightforward and sometimes repetitive prose, with a few notable digressions, like the discussion on power and friendship in a romance, and the description of the medium’s dingy house. Stein portrays brilliantly the tense confrontations between Anna and her (female) adversaries. At one point she describes Anna’s quite elaborate costume. One theme is female bonding, since the narrator insists on Anna’s "romance" with Mrs. Lehntman. Anna likes to work only for passive and big women who let her take care of everything, otherwise she prefers to work for men, because "Most women were interfering in their ways."

"The Good Anna" is indebted to Gustave Flaubert's Un Coeur Simple (the first of the Three Tales), which is about a servant and her eventual death (in both stories a parrot figures). But Stein’s Anna is much more determined and wilful than Flaubert’s Felicité, and, though generous to a fault, gets her way in most things.

"Melanctha"

edit"Melanctha," the longest of the Three Lives stories, is an unconventional novella that focuses upon the distinctions between, and blending of, race, sex, gender, and female health. Stein uses a unique form of repetition to portray characters in a new way. "Melanctha", as Mark Schorer depicts it on Gale's Contemporary Authors Online, "attempts to trace the curve of a passion, its rise, its climax, its collapse, with all the shifts and modulations between dissension and reconciliation along the way". But "Melanctha" is more than one woman’s bitter experience with love; it is a representation of internal struggles and emotional battles in finding meaning and acceptance in a tumultuous world.

The main character Melanctha, who is the daughter of a black father and a mixed-race mother in segregated Bridgepoint, goes on a quest for knowledge and power, as she is dissatisfied with her role in the world. Her thirst for wisdom causes her to undergo a lifelong journey filled with unsuccessful self-fulfillment and discovery as she attaches herself to family members, lovers, and friends, each representing physical, emotional, and knowledgeable power. She visualizes herself in relation to those around her, but is consistently unable to meet their expectations. And yet, for all the colorization and gendering of the characters, color and sex are incongruent to social and romantic success. "Melanctha" depicts each of its characters in racial degrees and categories, but their fates often run counter to what readers might expect.

Thoughts of suicide are often appealing to Melanctha, who finds herself "blue" and in despair. The last betrayal and Melanctha’s final blow, her close friend Rose's rejection of her, leaves her broken and ill. At the culmination of the novella, Melanctha is consumed, not so much by the physical illness that overtakes her, as by the despair she has felt throughout her life. She has often complained of feeling "sick," of being "hurt," and of having "pain," but perhaps this physical pain has always included a deep mental pain stemming from her experiences in life. Melanctha’s death from "consumption," as tuberculosis was then widely known, concludes the story.

Werner Sollors boldly declares: "Stein's merging of modernist style and ethnic subject matter was what made her writing particularly relevant to American ethnic authors who had specific reasons to go beyond realism and who felt that Stein's dismantling of the 'old' was a freeing experience...Strangely enough then, 'Melanctha' - which was, as we have seen, the partial result of a transracial projection - came to be perceived as a white American author's particularly humane representation of a black character."[4] "Melanctha" is an experimental work with complex racial, gender, and sexual constructs that leave room for interpretation.

"The Gentle Lena"

edit"The Gentle Lena", the third of Stein's Three Lives, follows the life and death of the titular Lena, a German girl brought to Bridgepoint by a cousin. Lena begins her life in America as a servant girl, but is eventually married to Herman Kreder, the son of German immigrants. Both Herman and Lena are marked by extraordinary passivity, and the marriage is essentially made in deference to the desires of their elders. During her married life, Lena bears Herman three children, all the while growing increasingly passive and distant. Neither Lena nor the baby survives her fourth pregnancy, leaving Herman "very well content now...with his three good, gentle children".

Background

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

Stein's first book, QED, went unpublished until after her death. She began another, The Making of Americans, in 1903 and finished it in 1911, but it took until 1925 to see print.[5] Stein's brother Leo, with whom she was living in Paris, encouraged her to attempt a translation of Flaubert's Three Tales to improve her French.[2] She then started writing Three Lives. She began the project in 1905[5] under the title Three Histories,[2] and finished it in 1909.[5]

As the book developed, Stein included and later dropped an authorial narrator, Jane Sands, perhaps named after George Sand, whose work she admired.[6] Among the titles the book went through as it progressed were The Making of an Author, Being a History of One Woman and Many Others.[7]

In 1904 Leo Stein bought Paul Cézanne's painting Portrait of Madame Cézanne (c. 1881), which depicts the artist's wife holding a fan while reclining in a high-backed red chair. This picture hung above Gertrude Stein's desk as she wrote Three Lives.[8] During this period, Picasso painted his Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906), in which the hairstyle, hands, and mask-like face resemble Cézanne's depiction of his wife.[9]

Style

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

In contrast to Stein's formally challenging later works, the narrative style of Three Lives is relatively straightforward.[10] Stein wrote in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas that an envoy from the book's publisher was surprised on visiting her to discover that she was American, and that she assured him the foreign-seeming syntax was deliberate.[11]

Stein admired both Flaubert and Cézanne for their devotion to means of expression rather than strict representation of their subjects. Stein wished to break from the naturalism then in vogue in American literature.[2] Her brother Leo had drawn her attention to compositional aspects of Cézanne's paintings, in particular his focus on the spatial relationships of the figures depicted rather than on verisimilitude.[2] Similarly, in her writing Stein focused on the relations of movement between characters, and intended that each part of the composition should carry as much weight as any other.[12]

Publication history

editStein's partner Alice B. Toklas helped prepare the proofs of Three Lives.[6] With its unconventional style, the book had difficulty finding a publisher. A friend of her brother Leo's, writer Hutchins Hapgood, tried to help find one, though he was pessimistic of the book's chances. Its first rejection came from Pitts Duffield of Duffield & Co., who recognized the book's French influence, but passed on its "too literary" and realistic qualities, which he believed would find few contemporary readers. Literary agent Flora Holly and Stein's friend Mabel Weeks were also unable to interest a publisher. After a year of rejections, another friend, Mary Bookstaver, found the vanity publisher Grafton Press of New York; Stein had the firm print Three Lives at her own expense for $660. It was her first published book. The 500 copies of its first printing left the presses on July 30, 1909.[13]

Reception and legacy

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

Stein sent copies to popular writers Arnold Bennett, H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and John Galsworthy, and hoped the book would be a commercial success. Sales were sparse, but the book was talked about in literary circles. William James, her psychology teacher at Johns Hopkins, called it "a fine new kind of realism".[14]

Though restrained in comparison to the works to follow, the book was seen as radical in style. Writer Israel Zangwill wrote, "... I always thought [Stein] was such a healthy minded young woman, what a terrible blow this must be for her poor dear brother."[10]

A reviewer for the Chicago Record-Herald wrote in early 1910 of the "analogous methods" of Stein and the subtle works of Henry James, who "presents us the world he knows largely through ... conversations"; Stein’s "murmuring people are as truly shown as are James' people who not only talk but live while they talk".[15]

Stein sent copies of the book to African-American writers W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington.[14] African-American reactions to Stein's portrayal of Melanctha varied: novelist Richard Wright wrote that he could "hear the speech of [his] grandmother, who spoke a deep, pure Negro dialect", while poet Claude McKay "found nothing striking and informative about Negro life. Melanctha, the mulatress, might have been a Jewess."[10]

Three Lives continues to be the most widely taught of Stein's books, considered more accessible than her later works,[16] such as the "Cubist" Tender Buttons which followed in 1914.[3]

References

edit- ^ [1] Stein, Gertrude. Writings 1903–1932. New York: Library of America, 1998, p. 928 ISBN 1-883011-40-X

- ^ a b c d e Daniel 2009, p. 68.

- ^ a b Leick 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Sollors 2008, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Watson 2005, p. 16.

- ^ a b Daniel 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Daniel 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Rowe 2011, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Rowe 2011, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Daniel 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Daniel 2009, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Daniel 2009, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Leick 2012, p. 26.

- ^ a b Daniel 2009, p. 73.

- ^ Watson 2005, p. 139.

- ^ Daniel 2009, p. 67; Leick 2012, p. 26.

Works cited

edit- Daniel, Lucy Jane (2009). Gertrude Stein. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-516-5.

- Leick, Karen (2012). Gertrude Stein and the Making of an American Celebrity. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-60345-7.

- Rowe, John Carlos (2011). Afterlives of Modernism: Liberalism, Transnationalism, and Political Critique. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-58465-996-9.

- Watson, Dana Cairns (2005). Gertrude Stein and the Essence of what Happens. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1463-9.

- Sollors, Werner (2008). "Gertrude Stein and 'Negro Sunshine'". Ethnic Modernism. Harvard University Press. pp. 17–34. ISBN 9780674030916.

Further reading

edit- Curnutt, Kirk (2000). The Critical Response to Gertrude Stein. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30475-0.

- Sollors, Werner (2002). Bercovitch, Sacvan (ed.). The Cambridge History of American Literature; Volume 6: Prose Writing, 1910-1950. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Stendhal, Renate, ed. (1989). Gertrude Stein In Words and Pictures: A Photobiography. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-0-945575-99-3.

External links

edit- Three Lives at Standard Ebooks

- Three Lives at Project Gutenberg

- Three Lives public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Quoting Gertrude Stein, blog discussing Gertrude Stein written by Renate Stendhal, author of Gertrude Stein in Words and Pictures