Thornicroft's giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti), also known as the Rhodesian giraffe or Luangwa giraffe, is a subspecies of giraffe. It is sometimes considered a species in its own right (as Giraffa thornicrofti)[2] or a subspecies of the Masai giraffe (as Giraffa tippelskirchi thornicrofti).[3][4][5] It is geographically isolated, occurring only in Zambia’s South Luangwa Valley.[6] An estimated 550 live in the wild, with no captive populations. Its lifespan is 22 years for males and 28 years for females.[7] The ecotype was originally named after Harry Scott Thornicroft, a commissioner in what was then North-Eastern Rhodesia and later Northern Rhodesia.

| Thornicroft's giraffe | |

|---|---|

| |

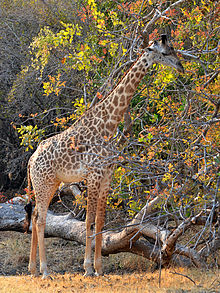

| Thornicroft's giraffe in Mfuwe, Zambia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Giraffidae |

| Genus: | Giraffa |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | G. c. thornicrofti

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti Lydekker, 1911

| |

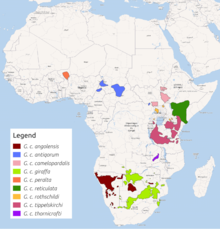

| |

| Range in purple | |

| Synonyms | |

|

G. thornicrofti | |

Description

editThornicroft's giraffes are tall with very long necks.[8] They have long, dark tongues and skin-colored horns.[9] Giraffes have a typical coat pattern, with regional differences among subspecies. The pattern consists of large, irregular shaped brown to black patches separated by white to yellow bands.[9] Male giraffes' coats darken with age, particularly the patches. The darkening of the coat has not been studied extensively enough to indicate absolute age; however, it can estimate relative age of male Thornicroft's giraffes.[7]

Range, distribution and habitat

editGiraffes occur in arid and dry-savannah zones in sub-Saharan Africa, provided trees are available as a food source. Thornicroft's giraffe is endemic to Zambia.[6] Giraffes are herd animals with a flexible social system.[10]

Diet

editGiraffes are exclusively browsers that primarily feed on leaves and shoots of trees and shrubs. They consume deciduous plants in the wet season and transition to evergreen and semi-evergreen species in the dry season, choosing flowers, fruits, and pods when they are available. They are true ruminants with forestomach fermentation. Their food intake is approximately 2.1% of the body mass of females and 1.6% for males. They can obtain their water through the foliage they consume, but drink regularly when water is available. Giraffes seek out acacia species when browsing. Their feeding stimulates shoot production of the species.[11]

Reproduction

editThornicroft's giraffes breed throughout the year. They reach sexual maturity at approximately six years, and then produce offspring approximately every 677 days. About half of all calves die before one year of age, mostly due to predation. Giraffes[which?] can become pregnant while lactating, an unusual characteristic.[12]

Conservation

editGiraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti is endemic to Zambia with a population of less than 550. There are none in captivity. Ecotourism has played a vital role in conservation of all subspecies of giraffes, due to their popularity with tourists. Giraffes as a species are classified as vulnerable according to the IUCN, but their populations are rapidly declining, with some subspecies being listed as critically endangered[13] Their primary threats are poaching, human population growth, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and habitat degradation.[14]

References

edit- ^ Bercovitch, F.; Carter, K.; Fennessy, J.; Tutchings, A. (2018). "Thornicroft's Giraffe". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Groves, Colin P. (2011). Ungulate taxonomy. Peter Grubb. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0329-8. OCLC 1202771597.

- ^ Fennessy, Julian; Bidon, Tobias; Reuss, Friederike; Kumar, Vikas; Elkan, Paul; Nilsson, Maria A.; Vamberger, Melita; Fritz, Uwe; Janke, Axel (2016). "Multi-locus Analyses Reveal Four Giraffe Species Instead of One". Current Biology. 26 (18): 2543–2549. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.036. PMID 27618261. S2CID 3991170.

- ^ Petzold, Alice; Hassanin, Alexandre (2020-02-13). Joger, Ulrich (ed.). "A comparative approach for species delimitation based on multiple methods of multi-locus DNA sequence analysis: A case study of the genus Giraffa (Mammalia, Cetartiodactyla)". PLOS ONE. 15 (2): e0217956. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1517956P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217956. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7018015. PMID 32053589.

- ^ Coimbra, Raphael T.F.; Winter, Sven; Kumar, Vikas; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Gooley, Rebecca M.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Fennessy, Julian; Janke, Axel (2021). "Whole-genome analysis of giraffe supports four distinct species" (PDF). Current Biology. 31 (13): 2929–2938.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.033. PMID 33957077. S2CID 233983230.

- ^ a b Fennessy, Julian, et al. "Mitochondrial DNA analyses show that Zambia's South Luangwa Valley giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti) are genetically isolated." African Journal of Ecology 51.4 (2013): 635–640.

- ^ a b Berry, P. S. M., and F. B. Bercovitch. "Darkening coat colour reveals life history and life expectancy of male Thornicroft's giraffes." Journal of Zoology 287.3 (2012): 157–160.

- ^ Wilson, and Reeder. "Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti." Mammal Species of the World. Bucknell University, n.d. Web. 2 May 2014.

- ^ a b Hassanin, Alexandre, et al. "Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa." Comptes Rendus Biologies 330.3 (2007): 265–274.

- ^ Bercovitch, Fred B., and Philip SM Berry. "Ecological determinants of herd size in the Thornicroft’s giraffe of Zambia." African Journal of Ecology 48.4 (2010): 962-971.

- ^ Owen-Smith, R. Norman. Megaherbivores: the influence of very large body size on ecology. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- ^ Bercovitch, Fred B., and Philip SM Berry. "Reproductive life history of Thornicroft’s giraffe in Zambia." African journal of ecology 48.2 (2010): 535–538.

- ^ Fennessy, J. & Brown, D. 2010. Giraffa camelopardalis. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 02 May 2014.

- ^ "Giraffe – The Facts”. Giraffe Conservation Foundation. Retrieved 2010-12-21.