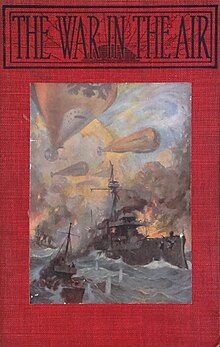

The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells and published in 1908.

First edition (UK) | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Published | 1908[1] |

| Publisher | George Bell & Sons(UK) Macmillan (US) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Serial, Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 389 |

| Text | The War in the Air at Wikisource |

The novel was written in four months[2] in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in The Pall Mall Magazine.

Like many of Wells's works, the novel is notable for its prophetic ideas, images, and concepts—particularly the use of aircraft for the purpose of warfare—as well as conceptualizing and anticipating events related to World War I. The novel's hero and main character is Bert Smallways, who is described as "a forward-thinking young man" and a "kind of bicycle engineer of the let's-'ave-a-look-at-it and enamel-chipping variety."[3]

Plot summary

editThe first three chapters of The War in the Air expound on details of the life of the novel's hero Bert Smallways and his extended family. They reside in a location called Bun Hill, a fictional, former Kentish village that had become a London suburb.

The chapters introduce Bert's brother Tom, a stolid greengrocer, who views technological progress with apprehension. Also introduced is their aged father, who recalls, with longing, the time when Bun Hill was a quiet village and he had been able to drive the local squire's carriage. The story soon shifts focus to Bert; an unimpressive, unsuccessful, not particularly gifted young man with few ideas about larger things. Bert is far from unintelligent, however and we come to know that Bert has a strong attachment to a young woman named Edna.

When bankruptcy threatens his business one summer, he and his partner abandon their shop and devise a singing act, calling themselves "the Desert Dervishes". They attempt to resolve their misfortunes by staging performances at English sea resorts. As chance would have, their initial performance is interrupted by a certain balloon that lands on the beach before them. The balloon contains a new character: Mr. Butteridge.

Butteridge is famous for his successful invention of an easily maneuverable fixed-wing aircraft, whose secret he has not revealed. We come to know that he intends to sell his secrets to the British government or, if not possible, instead to Germany. We also come to know that prior to Mr. Butteridge's invention, nobody had succeeded in producing a practical, "heavier-than-air" machine—only a few awkward devices of limited utility had been made since (such as the German "Drachenflieger" which had to be towed aloft and released from an airship). Butteridge's invention is considered a major breakthrough. The invention is highly maneuverable, capable of both very fast and very slow flight, and requires only a small area to take off and land—reminiscent of the later autogyro.

Later in the novel, Bert is carried off in Butteridge's balloon and ends up discovering Butteridge's secret plans while he is on board. Bert is clever enough to appraise his situation, and when the balloon is shot down in a secret German "aeronautic park east of Hamburg"[4] Bert tries to sell Mr. Butteridges's invention. However, he has unknowingly stumbled upon the German air fleet just as it is about to launch a surprise attack on the United States. Prince Karl Albert, the author and leader of the plan, decides to take him along for the campaign.

The Prince, world-famous as "the German Alexander" or Napoleon, is a living manifestation of German nationalism and boundless imperial ambitions—his personality as depicted by Wells in some ways resembling that of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Bert's disguise is soon seen through by the Germans, and, after he avoids being thrown overboard by the furious prince, he becomes relegated to the role of a witness to the true horror of war.

The German aerial forces, comprising airships and Drachenfliegers, are mounting their surprise attack on the United States before the Americans can build a large aerial navy; the pretext for the attack is a German demand for the US to abandon the Monroe Doctrine, so as to facilitate German imperial ambitions in South America. The Germans are, however, unaware that the "Confederation of Eastern Asia" (China and Japan) has secretly been building a massive air force. Tensions between Japan and the United States, exacerbated by the issue of American citizenship being denied to Japanese immigrants, leads to war breaking out between the Confederation of Eastern Asia and the US, whereupon the Confederation turns out to possess overwhelmingly strong aerial forces, and the US finds itself fighting a war on two fronts: the Eastern and the Western, in the air as well as on sea.

Bert Smallways is present as the Germans first attack an American naval fleet in the Atlantic, utterly obliterating it and proving dreadnoughts to be obsolete and helpless against aerial bombardment. The Germans then appear over New York City, bomb several key points, and establish that they have the city at their mercy, whereupon the mayor, with the consent of the White House, offers New York's surrender. However, the surrender announcement rouses the population's patriotic fury; local militias rebel and manage to destroy a German airship over Union Square using a concealed artillery piece. Following this, the vengeful prince orders a wholesale destruction, airships moving along Broadway and systematically raining death and destruction on the population below.

Following the destruction of New York, the far inferior American flying machines launch a suicidal attack on the overwhelming German force. They are almost completely obliterated, but cripple the Germans. The prince's flagship is disabled, and is unable to avoid being driven north by gale-force winds, eventually crashlanding in Labrador. Bert becomes an official member of the crew, as they struggle to survive in the freezing wilderness, befriends an English-speaking German junior officer, and for a time feels strong fellowship towards his crew mates. After a week they are picked up by another German airship, and carried directly into the fray of a ferocious new battle.

According to the prince's plans for the attack on the US, simultaneously with the subduing of New York, other German forces had landed at Niagara Falls, summarily evicted all the American population as far as Buffalo, and set to work building a large German airfield on American soil. However, the Asians – who have their own plans of conquest in America, and have already destroyed San Francisco – send their aerial forces over the Rocky Mountains and engage the Germans in battle, seeking to conquer or destroy the Niagara base.

The Asiatic air fleet is equipped with large numbers of lightweight one-man flying machines called Niais, which appear to be ornithopters, armed with a gun carried by the pilot firing explosive bullets "loaded with oxygen" (i.e. incendiary bullets) for use against the hydrogen-filled airships. The Asians prove overwhelmingly superior, and the German airships are either destroyed or forced to flee, eventually surrendering to the Americans; only a few remain with Prince Karl Albert, who attempts a heroic last stand.

Bert is stranded on Goat Island in the middle of Niagara Falls, where he finds a crashed Niais and discovers that Prince Karl Albert and a surviving German officer share the island with him. Their clash of personalities eventually culminates in a life-or-death confrontation, and Bert – originally gentle and sickened by bloodshed – overcomes his civilised scruples and kills the prince. Bert then manages to repair the Asian flying machine and escapes from the island on it, crash-landing near Tanooda, New York.

Upon making contact with local Americans, Bert learns that the Asiatic forces have landed "a million men" on the western seaboard. The original German–American conflict, which had set off the conflagration, is almost forgotten in the massive conflict with the Asian forces – a conflict carried out with great savagery, neither side taking prisoners. All over the US, Chinese Americans are being lynched and in some places the lynching extends to blacks as well.

Bert learns that the war is going badly for the Americans, who are unable to withstand the superior Asian flying machines; the Americans mourn the loss of the Butteridge machine which might have turned the tide, if its inventor had not died suddenly shortly before the outbreak of war, taking his secret with him. Bert discloses that the plans for Butteridge's flying machine are in his possession, whereupon a local militia leader named Laurier urges him to turn the plans over to the president.

After an adventurous ride through war-ravaged upstate New York they find the president hiding out in "Pinkerville on the Hudson." The president proceeds to have copies printed and distributed widely all over the US, as well as sent to Europe. However, the results are not quite as expected. A decisive Asiatic victory is, indeed, averted – but there is no American or European victory, either. The Butteridge machine is cheap, easy and quick to build, and needs no big fields to take off or land – which mean it can be built and operated not only by national governments, but also by private groups, local militias, and even bandits – a development which tends to break up the war into a vast, incoherent multitude of localised struggles and which accelerates the already-begun process of break-up and disintegration of the world's nations.

While Bert experiences directly the events in America, news about what has happened in the rest of the world (specifically, in his native England) is few and scattered, with newspapers reduced to a single page before finally ceasing publication altogether; still, he hears with great alarm that London had shared the fate of New York.

The omniscient author, whose point of view is that of a future historian documenting the war and its aftermath, reveals information not available to Bert. The German assault on the US had bypassed Germany's European rivals, whose air fleets were considered too puny to constitute a threat, with the intention of totally dominating them once the Americans had been subdued. However, the alarmed United Kingdom, France, Spain and Italy pooled their aerial resources into a single strong force, passed through Swiss airspace after destroying that country's own flying machines, and devastated Hamburg and Berlin. The Germans mobilised a counter-attack which destroyed London and Paris, but then, as in America, the feuding Europeans were faced with an enormous attack from Asia.

The Asiatic fleet had attacked a combined Anglo-Indian aerial force, captured the Burmese airfields, Australia, and the Pacific islands. They then struck westwards, capturing the Middle East and South Africa and starting to build airships at Cairo, Damascus and Johannesburg. Moving further northwards, they soon reached Armenia then defeating the German forces in the Battle of the Carpathians before attacking Western Europe.

A global financial collapse is caused by hostile nations freezing assets, and the end of the credit system. This is referred to as "the Panic," which is followed by "The Purple Death." The War in the Air, the Panic, and the Purple Death bring about "[w]ithin the space of five years" a total collapse of "the whole fabric of civilisation."[5] But Bert Smallways, fixated on his amorous attachment, returns home after many adventures to kill a rival and win the hand of his beloved Edna; they marry and have eleven children. We are assured in the final chapter that "our present world state, orderly, scientific, and secured,"[6] would be eventually established, but that future is many decades or centuries off. For the plot's present time, the novel reverts to the ensuing fortunes of the Smallways family as England relapses into a sort of an agricultural barbaric age, Bert Smallways doing very well as a kind of tribal chieftain, occasionally resorting to bloodthirsty acts and his civilized scruples long forgotten.

Themes

editThe story was written in 1907 and depicts a war happening in the late 1910s – then a future history, which can be considered as a retroactive alternate history. The basic assumption behind the plot is that immediately after the Wright brothers's first successful flight in 1903, all of the world's major powers became aware of the decisive strategic importance of air power, and embarked on a secret arms race to develop this power (there is a reference to the Wright Brothers themselves disappearing from public view, having been recruited for a secret military project of the US government – as were other aviation pioneers in their own respective countries). The general public is virtually unaware of this arms race, until it finally bursts out in a vastly destructive war which destroys civilisation.

In actual history, it took politicians and generals several decades to fully grasp these strategic implications. Moreover, the limited effect of the World War I German airship raids on London proved airships far from being the overwhelming destructive weapon depicted in Wells' book, nor were the early aeroplanes of the 1900s and 1910s capable of such massive bombings and destruction. Thus, the visions conjured by Wells were prophetic of the Second World War rather than the First one. (In fact, the actual First World war – characterised by very rigid fronts and a clear advantage of defence over offence – turned out to be the diametrical opposite of the one depicted by Wells, a completely fluid war with no clear fronts, and with a devastating offence against which no effective defence is possible.)

The latter parts of the book feature a post-apocalyptic theme – i.e., worldwide use of weapons of mass destruction and the war ending with no victors but with the total collapse of civilisation and the disintegration of all warring powers – which prefigures the themes of the later extensive literature depicting the aftermath of a Third World War. A similar theme appears in Wells' later The Shape of Things to Come. In a sense, "Things to Come" is a kind of sequel to The War in the Air. Though the details of the war in the latter book are different, its outcome is essentially the same – a complete disintegration of civilisation. "Things to Come" concentrates on the reconstruction of the world after this vast destruction and the creation of a peaceful, prosperous world state – and it depicts pilots and their aircraft as having a key role in re-building and unifying the world, just as they had a key role in destroying it. Also the major semi-historical chapters – interspersed in "The War in the Air" between the depictions of Bert Smallways' personal adventures, and written from the perspective of a future historian looking back with compassion at Twentieth Century people and their lethal nationalistic folly – clearly prefigure the tone of "Things to Come".

The idea of Japan and China uniting into a single power, the "Confederation of East Asia", prefigures "Eastasia" which is one of the three world powers in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty Four. The military might and ability attributed to the Sino–Japanese alliance is clearly and manifestly inflated: constructing far more airships and flying machines than all the rest of the world put together; waging simultaneous all-out wars of conquest against the United States, Britain, Germany, and other powers; performing the gigantic logistical task of transporting a million people across the Pacific within a few days while at the same time conducting extensive military operations all over Asia, Africa, Europe and North America.

As was pointed out by George Bright,[7] there was no way that a sober analysis of Japan and China's economic and military potential would have led Wells to attribute to them such might – even assuming, as the book does, an incredibly fast industrialisation of China, a backward and predominantly agrarian country at the time of writing. Rather, this theme is clearly linked to fears of the "Yellow Peril", which came about as a response to increasing Chinese emigration to the Western world.

Specifically, Wells' book is considered to have been influenced by M. P. Shiel's novel The Yellow Danger,[8] which also influenced novelist Jack London's The Unparalleled Invasion (1910).[9] A bit of scepticism on this issue is retained in The War in the Air in a passage where a German officer, hearing of the massive Asiatic offensive, remarks with astonishment: "The Yellow Peril was a peril, after all!".[10]

The recent Japanese success in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the first time when an Asian army had proved superior to a European one, was fresh in the memory of Wells' readers, the worldwide Asian assault depicted being in effect a monstrously magnified echo of the Japanese surprise attack on Port Arthur.

The background of Bert Smallways bears some resemblance to Wells' own – a working-class family in a London suburb (which is similar to Wells' native Bromley), with a struggling small shop. Jessica, Bert's strong-willed but narrow-minded sister in law – a former domestic servant who rose to a kind of petit bourgeois respectability and who tries to make Bert an errand boy in the family shop – resembles Wells' mother who intended him to be a draper. Bert seeks to break out of this background, as Wells did, but fails to gain the higher education which Wells got, and in the conditions of worldwide collapse he ends up as a semi-Medieval peasant eking out a bare subsistence.

Bert's basic moral attitudes go through three distinct stages. To begin with, he tends to glorify war, patriotism and jingoism, and supports his nation becoming involved in wars in a haze of quasi-patriotic fever – this in a shallow way, derived from the popular press and without having or expecting to have a personal experience of war and bloodshed. When on board the German air fleet, Bert is exposed to a mounting series of horrors and bloody scenes which make him increasingly sickened. The same process is shared with Lieutenant Kurt, the young English-speaking German whom Bert befriends; a professional military officer, Kurt had in fact not witnessed war before, either, and he is equally sickened and vehemently rejects the idea that people should be "blooded" to make them used to violence and bloodshed. When marooned on Goat Island and finding himself locked in a deadly confrontation with the two equally marooned Germans, Bert is full of compunctions and does not want to kill them. After having killed the Prince, Bert speaks to the kitten he had rescued in the middle of all the carnage, telling the innocent little creature of his regrets at having committed this act. Moreover, Bert does spare the other German officer roaming the island, even when having him in his gun sights. Nevertheless, Bert did become "blooded" through the killing of the Prince, and undergoes further unspecified "violent incidents" during his harrowing crossing of the Atlantic and then while crossing on foot a starving English countryside which is fast reverting to barbarism. A year later, he returns to his beloved Edna and discovers she is being intimidated by a local strongman seeking to add her to his "harem". Bert feels no hesitation or compunction about shooting the man out of hand and taking over his gang.

Wells later republished several of his works with William Heinemann of London, who had recently been purchased by Doubleday. These versions contained numerous edits to the works and are collectively referred to as the "Heinemann text". In this 1924 version, Bert and Edna live happily ever after, producing eleven children. In the epilogue of this version, we meet up with Bert's brother, Tom, again. Tom is now an "old man" at 63 years of age, and speaks to the youngest of Bert's children, his nephew Teddy, about "the good old days." He recounts his time as a prosperous greengrocer, and describes an abundant life that his nephew finds hard to believe. He then follows through, describing all the events that happened "back home," offering correlation to Bert's adventure in the rest of the text. Although events differ between the brothers' stories, the sentiment of civilization's unraveling is presented in much the same emotion of regret and loss, showing similarity to Bert's earlier feelings on life events. Tom is surprised and disturbed to find his nephew "was blooded" when he was only six years old, exhibiting Bert's apparent change in attitude toward that process. Tom goes on to relate ghost stories to his nephew, weaving in the characters mentioned by the narrator in the first few chapters. Tom describes the sequence of events that caused the destruction of Bun Hill, and in the end Teddy agrees that it "shouldn't have happened" the way it did. We leave Tom in his conviction that "somebody somewhere ought to have stopped something" and "it ought not to have ever begun."

Reception

editOne biographer has called The War in the Air "an extraordinary concoction—as if H.G. had shaken up Kipps and The War of the Worlds and poured out a new story that would appeal both to those who liked his social comedies and those who had been impressed by his early fantasies of terror."[11] Beatrice Webb annoyed Wells by preferring The War in the Air to Tono-Bungay, which Wells regarded as his masterpiece.[12]

Influence

edit- The War in the Air is part of the historical backdrop of Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill's series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, as described in The New Traveller's Almanac.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Facsimile of the original 1st edition

- ^ Arnold Bennett's diary is the source of this information, which states that the book earned 3,000 pounds for Wells. Norman and Jeanne Mackenzie, H.G. Wells: A Biography (Simon and Schuster, 1973), p. 234. Wells wrote Tono-Bungay concurrently but regarded the latter as so superior artistically that he ultimately finished up The War in the Air in order to get it out of the way, so that he could concentrate his efforts on the more important novel. David C. Smith, H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal: A Biography (Yale UP, 1986), p. 203.

- ^ H.G. Wells, The War in the Air, Ch. 1, §2

- ^ H.G. Wells, The War in the Air, Ch. 3, §5.

- ^ H.G. Wells, The War in the Air, Ch. 11, §1.

- ^ H.G. Wells, The War in the Air, Ch. 11, §1.

- ^ George A. Bright, "The Magnified and Distorted Image of The Orient", Forward, Ch. 2

- ^ Squires, "The Dragon's Tale", 299.

- ^ Yorimitsu Hashimoto, "Germs, Body-Politics and Yellow Peril: Relocation of Britishness in The Yellow Danger," Australasian Victorian Studies Journal (Vol. 9, 2003,) 56.

- ^ "The War in the Air", Ch. VII, 7

- ^ Noman and Jeanne Mackenzie, H.G. Wells: A Biography (Simon and Schuster, 1973), p. 222.

- ^ Michael Sherborne, H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life (Peter Owen, 2010), pp. 185–86.

Further reading

edit- Mollmann, Steven (March 2015). "Air-Ships and the Technological Revolution: Detached Violence in George Griffith and H.G. Wells". Science Fiction Studies. 42 (1): 20–41. doi:10.5621/sciefictstud.42.1.0020. JSTOR 10.5621/sciefictstud.42.1.0020.

External links

edit- The War in the Air at Project Gutenberg

- The War in the Air public domain audiobook at LibriVox