The Express: The Ernie Davis Story is a 2008 American sports drama film produced by John Davis and directed by Gary Fleder. The storyline was conceived from a screenplay written by Charles Leavitt from a 1983 book Ernie Davis: The Elmira Express, authored by Robert C. Gallagher. The film is based on the life of Syracuse University football player Ernie Davis, the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy, portrayed by actor Rob Brown. The Express explores civil rights topics, such as racism, discrimination and athletics. It was the film debut of Chadwick Boseman as Floyd Little.[2]

| The Express: The Ernie Davis Story | |

|---|---|

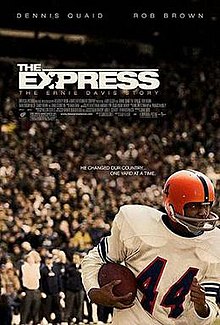

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Gary Fleder |

| Written by | Charles Leavitt |

| Based on | Ernie Davis: The Elmira Express by Robert C. Gallagher |

| Produced by | John Davis |

| Starring | Dennis Quaid Rob Brown Omar Benson Miller Clancy Brown Charles S. Dutton |

| Cinematography | Kramer Morgenthau |

| Edited by | Padraic McKinley William Steinkamp |

| Music by | Mark Isham |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $40 million[1] |

| Box office | $9.8 million[1] |

The film was a co-production between the film studios of Relativity Media and Davis Entertainment. It was commercially distributed by Universal Pictures theatrically, and by Universal Studios Home Entertainment for home media. Dennis Quaid and Charles S. Dutton star in principal supporting roles. The original motion picture soundtrack with a musical score composed by Mark Isham, was released by the Lakeshore Records label on October 28, 2008.

The Express premiered in theaters nationwide in the United States on October 10, 2008. Despite receiving generally positive reviews from critics, the film was a box office bomb, grossing just $9.8 million against its $40 million budget. The Blu-ray version of the film, featuring deleted scenes and the director's commentary was released on January 20, 2009.

Plot

editErnie Davis is a young African American growing up in Pennsylvania with his uncle Will Davis Jr. in the late 1940s. Davis lives with his extended family, including his grandfather, Willie 'Pops' Davis, who guides and educates him. Davis' mother, Marie Davis eventually returns to their residence to inform the family that she has remarried and can now afford to raise Ernie at her own home in Elmira, New York. Upon relocating to Elmira, Davis enrolls in a Small Fry Football League and excels on the field as a running back.

Several years later, Syracuse University football head coach Ben Schwartzwalder searches for a running back to address the absence of Jim Brown, the graduating player completing his All-American senior season. Schwartzwalder is impressed with Davis after viewing footage of him playing for Elmira Free Academy and took his team to a state championship. Schwartzwalder convinces Brown to accompany him on a recruiting visit to see Davis and his family in hopes of luring him to commit to Syracuse. After their visit, Davis decides to enroll at Syracuse and spurns the recruiting efforts of other colleges.

At the start of the 1959 college football season, Davis immediately excels playing for the varsity team, to lead Syracuse to victories over several college football teams. After Syracuse defeats UCLA to conclude the regular season undefeated, the team decides by choice to play the 2nd ranked Texas Longhorns in the Cotton Bowl Classic. Before the game, university officials receive letters threatening attacks to Davis if he plays, but both Schwartzwalder and Davis defy the threats. During the game on January 1, 1960, Davis boldly attempts to lead his team to victory but is hampered by an injured leg and biased officiating. Towards the end of the game, Davis scores a crucial touchdown to preserve a Syracuse lead. The matchup concludes with a victory for Syracuse, and its first national championship. After the game, a banquet is held for the two teams, but when Davis is not allowed to attend, the rest of the Syracuse team leaves with him in a show of solidarity.

In 1961, Davis goes on to win the Heisman Trophy following his senior season in college. He later becomes a professional athlete in the National Football League and signs a contract with the Cleveland Browns. Later, however, following a series of health concerns, Davis is taken to a hospital to undergo medical testing. During a routine practice session, team owner Art Modell informs Davis he will be unable to play the upcoming season due to his condition. Subsequently, Davis holds a press conference and announces he has been diagnosed with leukemia. No longer able to play, Schwartzwalder asks Davis to accompany him on a recruiting trip, to talk to highly prized prospect Floyd Little, who shows to be as much in awe of Davis as Davis had been earlier with Jim Brown. The Cleveland Browns honor Ernie by allowing him to suit up in uniform and join the team while running out before a televised game. Prior to the game, Schwartzwalder meets Davis and tells him that Little has decided to play at Syracuse.

The film's epilogue displays a series of graphics stating that Davis died on May 18, 1963, at the age of 23; while in condolence, President Kennedy expresses sympathy for Davis' fine character as a citizen and an athlete.

Cast

edit- Rob Brown as Ernie Davis

- Dennis Quaid as Ben Schwartzwalder

- Omar Benson Miller as Jack Buckley

- Aunjanue Ellis as Marie Davis

- Clancy Brown as Roy Simmons

- Darrin Dewitt Henson as Jim Brown

- Saul Rubinek as Art Modell

- Nelsan Ellis as Will Davis, Jr.

- Charles S. Dutton as Willie "Pop" Davis

- Geoff Stults as Bob Lundy

- Evan Jones as Roger "Hound Dog" Davis

- Nicole Beharie as Sarah Ward

- Chelcie Ross as Lew Andreas

- Enver Gjokaj as Dave Sarette

- Maximilian Osinski as Gerhard Schwedes

- Chadwick Boseman as Floyd Little

Production

editDevelopment

editThe premise of The Express is based on the true story of Ernie Davis, the charismatic athlete who became the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy, college football's greatest achievement. Excelling in high school football, Davis was later recruited by dozens of predominantly white universities. A local sports columnist dubbed him the Elmira Express.[3] Davis was told of his terminal illness, leukemia, during the summer of 1962.[3] According to a saddened Art Modell, he said "They told him as gently as they could that it was an incurable case of leukemia. It was awful, but the way he took it, it seemed like much more of a blow to me and his teammates than it was to him."[3]

Following the NFL draft which saw the Washington Redskins trade their pick of Davis to Cleveland for Hall of Fame running back Bobby Mitchell, Davis signed a $100,000 contract with the Browns.[3] On May 16, 1963, Davis visited Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell. He promised to make a career comeback even though he looked terminally ill.[4] Two days later on May 18, Davis died from the then-incurable disease. Fellow teammate and close friend John Brown, remembered him as a "genuine gentle man as well as a gentleman."[4] President John F. Kennedy called Davis "an outstanding young man of great character" and "an inspiration to the young people of this country."[4] The book titled Ernie Davis: The Elmira Express, authored by writer Robert C. Gallagher, became the basis for the film.

Set design and filming

editFilming began in April 2007 at Chicago area locations including Lane Technical High School, Amundsen High School, J. Sterling Morton West High School in Berwyn, Northwestern University in Evanston (at Ryan Field, the Northwestern Football stadium), Aurora, Mooseheart, the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Hyde Park (at the former Windemere Hotel) and at Memorial Park and on Walnut Street and Olde Western Ave. in Blue Island.[5] It concluded its fifty-three-day shoot at Syracuse University.[6] Meticulous research was undertaken over several months to recreate the period uniforms and locations depicted, including the creation on film of several stadiums such as Archbold Stadium, that no longer exist. Existing buildings that were not on the Syracuse University campus had to be digitally removed from shots, such as the Carrier Dome.

Soundtrack

editThe original motion picture soundtrack for The Express was released by the Lakeshore Records label on October 28, 2008. It features songs composed with considerable use of the violin, trombone and cello. The score for the film was orchestrated by Mark Isham.[7] Michael Bauer edited the film's music. Original songs written by musical artists Vaughn Horton, Frankie Miller, Ralph Bass, Ray Charles, and Lonnie Brooks, among others, were used in-between dialogue shots throughout the film.[8]

| The Express: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | October 28, 2008 |

| Length | 49:28 |

| Label | Lakeshore Records |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Prologue" | 1:31 |

| 2. | "Jackie Robinson" | 2:06 |

| 3. | "Elmira" | 1:57 |

| 4. | "Lacrosse" | 2:07 |

| 5. | "Training" | 4:17 |

| 6. | "A Meeting" | 1:17 |

| 7. | "A Good Man" | 5:45 |

| 8. | "I'm Staying In" | 1:18 |

| 9. | "Cotton Bowl" | 7:36 |

| 10. | "Don't Lose Yourselves" | 4:43 |

| 11. | "Ernie Davis" | 1:37 |

| 12. | "Heisman" | 1:12 |

| 13. | "Draft" | 2:35 |

| 14. | "Rain" | 1:51 |

| 15. | "I'm An Optimist" | 2:46 |

| 16. | "What Kind of Bottle" | 1:49 |

| 17. | "The Express" | 5:02 |

| Total length: | 49:28 | |

Historical inaccuracies

editJournalists and film critics noted that a scene of "racist vitriol"[9] involving the October 24, 1959, game between Syracuse and West Virginia University was fictitious and, as Film Journal International critic Frank Lovece noted, "veers remarkably toward outright slander."[10] He further points out that the game was "falsely shown as taking place at WVU's Mountaineer Field" in Morgantown, West Virginia, "rather than at Syracuse's own Archbold Stadium," the Orangemen's home field at that time in New York state. Syracuse quarterback Dick Easterly, who played with Davis, said shortly after the movie's release, "I don't blame people in West Virginia for being disturbed. The scene is completely fictitious."[11]

The film suggests that Syracuse University had to win the 1960 Cotton Bowl to be named college football's national champion, when in fact the selection was made at the end of the regular season. This practice did not change until the late '60s.

Bobby Lackey, quarterback for the 1959 Texas Longhorns, stated in 2008 that the racial tensions and Longhorn behavior depicted in the New Year's Day 1960 Cotton Bowl Classic were made-up "stories to try and sell more movie tickets", and justifies the action of his roommate, Larry Stephens, as just "trying to get the guy (Davis) into a fight so he could get him thrown out of the game because their athletes were so much better than ours."[12] However, John Brown, a black offensive tackle for Syracuse, stated that there were "guys who called us racist names on the field", including a Texas lineman who kept calling him "a big black dirty [expletive]."[13] Brown says that the player has since apologized and that he has forgiven the player. Additionally, Al Baker, Syracuse's black fullback, said after the game, "Oh, they were bad. One of them spit in my face as I carried the ball through the line."[14][15] Patrick Whelan and Dick Easterly, both white players for Syracuse, said that although the film may have fictionalized parts of the story, the 1960 Cotton Bowl Classic was the team's worst confrontation with racism.[16]

Other inaccuracies are more along the line of the discrepancies in any fictionalized depiction of historical events. For example, the film places the 1959 Penn State game in the first three of Syracuse's season, with Syracuse winning 32–6, when it was actually the seventh game and Syracuse had their toughest challenge of the season, winning a close 20–18 game to advance to a 7–0 record. The order of scoring in the 1960 Cotton Bowl Classic was adjusted in the film for dramatic tension. Syracuse actually won the Cotton Bowl 23-14, but the film claims that the final score was 23-15, and that Texas had a chance to tie on the game's last play.

Art Modell is shown giving Jim Brown his first Cleveland Browns jersey in a photo op, but Modell did not purchase the Browns until four years after Brown joined the team. The scene in which Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall and Modell arrange a major trade was actually made by Browns coach and general manager Paul Brown behind Modell's back, adding to the tension between the two.

Reception

editCritical response

editOn review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 61% based on 114 reviews, with an average rating of 6.2/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "This inspirational sports biopic set in the civil rights era is interesting even for non-football fans, and features a great performance by Dennis Quaid as tough-but-fair football coach."[17] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average to reviews, the film received a score of 58 based on 27 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[18] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[19]

Roger Ebert wrote: "The Express is involving and inspiring in the way a good movie about sports almost always is. The formula is basic and durable, and when you hitch it to a good story, you can hardly fail. Gary Fleder does more than that in telling the story of Ernie Davis ("The Elmira Express"), the running back for Syracuse who became the first African-American to win the Heisman Trophy, in 1961."[20] Jim Lane, writing in the Sacramento News & Review, said of actor Brown, "the 16-year-old newcomer held his own with Sean Connery; here, he carries the film in partnership with Dennis Quaid".[21] Impressed, he exclaimed, "The film is predictable but inspiring, without going overboard into Brian’s Song tear-jerking. Fleder (expertly assisted by cinematographer Kramer Morgenthau and editors Padraic McKinley and William Steinkamp) ices the cake with some first-rate game footage."[21] Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times called it "special" while remarking, "There is a lot of football in the movie. It's well presented, but there is the usual oddity that it almost entirely shows mostly success."[20]

In the San Francisco Chronicle, Peter Hartlaub wrote that the film "deserves plenty of credit for abandoning the "Remember the Titans"/"Glory Road" school of screenwriting as laid out above and exploring the racial issues in Davis' story in more realistic terms." He thought Quaid gave a "memorable performance" by portraying Schwartzwalder as "sort of an accidental civil rights hero."[22] Mike Clark of USA Today, said the film was "an entertaining race-laced contest of wills". He found the football scenes filled with "kinetic" energy, and the lead performances to be "appealing".[23] The film however, was not without its detractors. Peter Rainer of The Christian Science Monitor, believed the film was a "compendium of virtually every sports movie cliché ever contrived" and that the storyline was "milked for every drop of inspirational uplift."[24] Left equally unimpressed was Anthony Quinn of The Independent. Commenting on the segregational history, he said "we have to suffer apologetic non-dramas like this, the story of a fleet-footed black footballer (Rob Brown) who hits the big time just as his racial conscience starts to bother him". He thought the screenplay was "stewed in such pieties, served up as warm and homely as apple pie – only there's no taste to it."[25] Graham Killeen of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, added to the negativity by saying, "Producer John Davis (The Firm, Behind Enemy Lines), no relation to Ernie, and director Gary Fleder (Kiss the Girls, Don't Say a Word) are masters of the predictable, the safe and the bland. And Davis' story doesn't play to their strengths." He ultimately called the film "an all-brawn, no-brain pigskin potboiler".[26]

Writing for the Boston Herald, Stephen Schaefer said the subject matter was a "paean to a supremely talented if largely unfamiliar sports hero, one which scores both on and off the field."[27] James Berardinelli writing for ReelViews, called the film "an engaging and at times powerful tale of one individual's struggle against the system" and noted that "as a story of courage and inspiration, this works as well as any sports-related bio-pic."[28] Berardinelli also thought that although Ernie's depiction of "on-field accomplishments were extraordinary, it was the environment in which he struggled to achieve them that makes him the worthy subject of a motion picture."[28] Describing some pitfalls, Wesley Morris of The Boston Globe said the film was "especially egregious since it bundles the civil rights era, garden-variety bigotry, and the achievements of Ernie Davis". He didn't believe Davis was "as bland as "The Express" makes him out to be. Aside from managing to get made at all, the movie doesn't do Davis's legacy any favors by giving us the store-brand version of his life."[29] Morris however, was quick to admit "There is so much ripe material here for a socially or historically curious movie." But he frustratingly noted that the filmmakers were more interested in "making a safely commercial football drama that doesn't deviate from the genre's shorthand imagery and plot points."[29]

The movie hints at the complexity of Brown's natural truculence and the chip racism left on his shoulder. But The Express ultimately settles for making him a big glass of tall, dark, and handsome, a neutered personality deployed to spout platitudes.

— Wesley Morris, Boston Globe[29]

Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post, stated that The Express "finesses a cinematic hat trick: It's entertaining, deeply moving and genuinely important."[30] She praised the individual cinematic elements saying the motion picture was "Filmed with pulverizing accuracy, they bristle not only with physical action but also historical and political symbolism."[30] She also complimented the lead acting by mentioning, "As warm as Brown's portrayal of Davis is, it's Dennis Quaid as Syracuse coach Ben Schwartzwalder who provides the movie's most fascinating figure."[30] Similarly, John Anderson wrote in Variety that the film was "a muscular movie with social conscience that portrays Ernie Davis – the first African-American collegian to win college football's coveted Heisman Trophy – as the heir to Martin Luther King and Jackie Robinson." On its production merits, he commented how the film displayed "Terrific editing by William Steinkamp and Padraic McKinley" which "intermarries the onfield action, flashbacks to Davis' Southern boyhood, a smattering of period footage and a great deal of stylized visualization to a degree that distracts from the very basic sports-movie arc of the story".[31] However, on a negative front in The Village Voice, Robert Wilonsky was not moved by the lead acting of Quaid or Brown. He thought Brown portrayed Davis with "quiet subtlety (to the point where he almost disappears in some scenes)" and felt Quaid was "stuck with the thankless role of accidental civil-rights pioneer". He summed up his disappointment stating, "like all formulaic biopics, The Express sacrifices the details for the Big Picture—hagiography without the humanity (wait, is that his girlfriend? Wife? What?), populated by sorta-enlightened Yankees, rabidly racist Southerners, and a ghost who remains as elusive as the running back no defender could ever catch."[32]

Box office

editThe film premiered in cinemas on October 10, 2008, in wide release throughout the U.S.. During its opening weekend, the film opened in a distant 6th place grossing $4,562,675 in business showing at 2,808 locations.[1] The film Beverly Hills Chihuahua soundly beat its competition during that weekend opening in first place with $17,502,077.[33] The film's revenue dropped by 52% in its second week of release, earning $2,191,810. For that particular weekend, the film fell to 12th place screening in 2,810 theaters but not challenging a top ten position. The film Max Payne, unseated Beverly Hills Chihuahua to open in first place grossing $17,639,849 in box office revenue.[34] During its final week in release, The Express opened in 31st place grossing $151,225 in business.[35] The film went on to top out domestically at $9,793,406 in total ticket sales through a 4-week theatrical run. Internationally, the film took in an additional $14,718 in box office business for a combined worldwide total of $9,808,124.[1] For 2008 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 146.[36]

Home media

editFollowing its cinematic release in theaters, the Region 1 code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on January 20, 2009. Special features for the DVD include; deleted scenes with optional commentary by director Gary Fleder; "Making of The Express"; "Making History: The Story of Ernie Davis"; "Inside the Playbook: Shooting the Football Games"; "From Hollywood to Syracuse: The Legacy of Ernie Davis"; and feature commentary with director Gary Fleder.[37] During its release in the home media market, The Express ranked number eleven in its first week on the DVD charts, selling 97,511 units totalling $1,949,245 in business.[38] Overall, The Express sold 370,534 units yielding $6,566,801 in revenue.[38]

The widescreen high-definition Blu-ray Disc version of the film was also released on January 20, 2009. Special features include "Making of The Express"; "Making History: The Story of Ernie Davis"; "Inside the Playbook: Shooting the Football Games"; "From Hollywood to Syracuse: The Legacy of Ernie Davis"; "50th Anniversary of the 1959 Syracuse National Championship"; and deleted scenes with optional commentary by director Gary Fleder.[39]

See also

editReferences

edit- Footnotes

- ^ a b c d "The Express". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Gary Fleder. (2008). The Express [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

- ^ a b c d "Ernie Davis' legacy lives on long after his death". National Football League. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Why Ernie Davis Matters". History News Network. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Salles, Andre (June 13, 2007). "'The Express' stops in Aurora". Archived from the original on June 16, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). The Beacon News. Retrieved 2010-08-08. - ^ The Express’ to Film Scenes on Campus Next Week; Extras Needed Archived January 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. suathletics.com. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Express Original Motion Picture Soundtrack Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "The Express (2008)". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Anderson, John (September 28, 2008). The Express Archived October 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (October 2008). The Express Archived September 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Film Journal International. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Thompson, Matthew (October 8, 2008). New movie shows WVU fans in false, ugly light Archived October 11, 2008, at archive.today. Charleston Daily Mail. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Golden, Cedric (October 10, 2008). The Express isn't a flattering portrait of Texas football Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. statesman.com. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Cogill, Gary (October 15, 2009). The Express (PG) Archived March 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. WFAA. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Krizak, Gaylon (September 17, 2008). Utility Infielder: 'The Express' unenlightens Horns Archived July 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Merron, Jeff (October 9, 2008). 'The Express' in real life . ESPN. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ Persall, Steve (October 5, 2008). Teammates say 'The Express' changes history Archived October 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ The Express (2008) Archived August 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ The Express Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Metacritic. CNET Networks. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 8, 2008). The Express Archived November 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b Lane, Jim (October 9, 2008). The Express. Sacramento News & Review. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (October 10, 2008). Movie review: 'The Express' Archived October 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Clark, Mike (October 10, 2008). Davis biopic 'The Express' doesn't fumble the telling Archived August 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. USA Today. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Rainer, Peter (October 11, 2008). Review: 'The Express' Archived November 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Quinn, Anthony (December 5, 2008). The Express (PG) Archived November 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Independent. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Killeen, Graham (October 10, 2008). ‘The Express’ is slow train to mediocrity Archived October 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Schaefer, Stephen (October 10, 2008). 'Express wins gridiron glory Archived October 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston Herald. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b Berardinelli, James (October 2008). The Express Archived January 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. ReelViews. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b c Morris, Wesley (October 10, 2008). 'Express' doesn't stray from safe playbook Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ a b c Hornaday Ann, (October 10, 2008). 'The Express': A Tale of Football and Awakening Archived September 22, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Anderson, John (September 28, 2008). The Express Archived October 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Variety. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Wilonsky, Robert (October 8, 2008). The Express Makes a Footnote into a Legend Archived January 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The Village Voice. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ "October 10–12, 2008 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ "October 17–19, 2008 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ "October 31-November 2, 2008 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "2008 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ "The Express Widescreen DVD". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ a b "The Express". The Numbers. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ "The Express Widescreen Blu-ray". Barnes & Noble. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- Further reading

- Gallagher, Robert (2008). Ernie Davis: The Elmira Express, the Story of a Heisman Trophy Winner. Bartelby Pr. ISBN 978-0-910155-75-5.

- Gallagher, Robert (2008). The Express: The Ernie Davis Story. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-51086-0.

- Burch, Coralee (2008). A Halo For A Helmet: The Whole Story Of Ernie Davis. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4404-3930-8.

- Youmans, Gary (2003). The Story of the 1959 Syracuse University National Championship Football Team. Campbell Road Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-8139-7.

- Pennington, Bill (2004). The Heisman: Great American Stories of the Men Who Won. Harper Entertainment. ISBN 978-0-06-055471-2.

- Levy, Bill (2004). Return to Glory. Nicholas Ward Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9760447-2-7.

- Davis, Barbara (2006). Syracuse African Americans. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3880-8.