That'll Be the Day is a 1973 British coming of age drama film directed by Claude Whatham, written by Ray Connolly, and starring David Essex, Rosemary Leach and Ringo Starr. Set primarily in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it tells the story of Jim MacLaine (Essex), a British teenager raised by his single mother (Leach). Jim rejects society's conventions and pursues a hedonistic and sexually loose lifestyle, harming others and damaging his close relationships. The cast also featured several prominent musicians who lived through the era portrayed, including Starr, Billy Fury, Keith Moon and John Hawken. The film's success led to a sequel, Stardust, that followed the life of Jim MacLaine through the 1960s and 1970s.

| That'll Be the Day | |

|---|---|

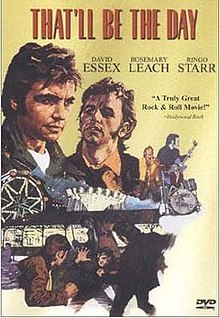

DVD cover by Arnaldo Putzu | |

| Directed by | Claude Whatham |

| Written by | Ray Connolly |

| Produced by | Sanford Lieberson David Puttnam |

| Starring | David Essex Rosemary Leach Ringo Starr James Booth Billy Fury Keith Moon |

| Cinematography | Peter Suschitzky |

| Distributed by | Anglo-EMI Film Distributors |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £288,000[1] |

Plot

editIn an urban area in early 1940s England, a young child, Jim MacLaine, lives with his mother Mary and grandfather. His seaman father returns, spends time with him, and works in the family's grocery shop. However, he finds himself unable to settle down and soon leaves again for good, abandoning his wife and son, and Mary continues to run the shop and raise Jim on her own.

In the late 1950s. Jim is now a very bright but bored schoolboy in his final year at the local secondary school. His mother wants him to do well on his final exams, qualify for university, and have many opportunities—but Jim is far less enthusiastic about continuing his education, preferring to draw, write poetry, listen to rock n' roll, and chase girls—unsuccessfully. Instead of going with his friend Terry to take his exams, he runs away to the coast to work as a deckchair attendant, disappointing and upsetting his mother. He moves on to a barman job at a holiday camp, where he befriends the experienced barman Mike, who helps him hook up with willing women for his first sexual experiences. Jim is also drawn to the music and lifestyle of the resident singer, Stormy Tempest, and his drummer, J.D. Clover.

Mike and Jim next get jobs at a funfair, supplementing their meager pay by short-changing customers. Jim quickly becomes a heartless fairground Romeo, having one-nighters with a wide variety of women, including a young schoolgirl whom he rapes. He lies to Mike about the encounter, but Mike sees through it and berates him. Shortly afterwards, Mike short-changes a gang member and is attacked by the whole gang. Jim sees Mike being beaten, but instead of helping him, Jim hurries away, pretending he saw nothing, and has a tryst with another fair worker. The severely injured Mike is hospitalized, and Jim gets a promotion that was supposed to be Mike's.

Jim contacts Terry, who is now at university, but discovers that Terry and the girls there look down on his lifestyle and musical tastes. After two years gone, Jim decides to return home, finding his resentful mother struggling to run the grocery shop and care for her father, who is now an invalid. Jim helps his mother with the shop and starts dating Terry's sister Jeanette over the objections of her mother and Terry. Unlike all his previous dates, Jim does not have sex with Jeanette, even though she is willing to do so out of love for him. Jim and Jeanette marry, with Terry and her mother wrongly assuming she must be pregnant. Jim, angry at Terry and ambivalent about losing his freedom, has sex with Terry's girlfriend Jean the night before his wedding.

Jim and Jeanette live with his mother and grandfather. Jim pretends to be going to night school, but is secretly spending his nights at rock n' roll shows. Jeanette gets pregnant and they have a son. Jean and Terry plan to get engaged, and Jean makes suggestive remarks to Jim in front of Jeanette.

After talking with friends in a band, Jim leaves home, repeating his father's pattern. Jeanette cries, but his mum is unsurprised. The film ends as Jim buys a secondhand guitar.

Cast

edit- David Essex as Jim MacLaine

- Ringo Starr as Mike

- Rosemary Leach as Mary MacLaine

- James Booth as Mr. MacLaine

- Billy Fury as Stormy Tempest

- Rosalind Ayres as Jeanette Sutcliffe

- Keith Moon as J.D. Clover

- Robert Lindsay as Terry Sutcliffe

- James Ottoway as Grandad

- Deborah Watling as Sandra

- Brenda Bruce as Doreen

- Beth Morris as Jean

- Daphne Oxenford as Mrs. Sutcliffe

- Kim Braden as Charlotte

- Johnny Shannon as Jack

- Karl Howman as Johnny

- Patti Love as Sandra's Friend

- Sue Holderness as Shirley

- Érin Geraghty as Joan

- Sara Clee as Girl With Baby

- Sacha Puttnam as Young Jim Maclaine

- John Hawken as Stormy Tempest Keyboard Player

Production

editDevelopment

editDavid Puttnam and his producing partner Sandy Lieberson met with Nat Cohen of EMI Films who agreed to provide half the budget. The other half, £100,000, was obtained from Ronco Records on the condition that the film include 40 songs from Ronco's catalog of old hits, which they could then sell on TV as a soundtrack album.[2][3]

Writing

editAccording to screenwriter Ray Connolly, the film was Puttnam's idea, who had worked in advertising and recently moved into film production. Connolly says Puttnam was inspired by Harry Nilsson's song "1941", in which an early-1940s father deserts his young son, who subsequently joins a circus; Puttnam suggested changing the circus to a fair.

Puttnam hired Connolly, a journalist friend, to write the script.[2] Connolly worked on it in the evenings, and said they would "ransack our own lives as we created the fictional character of Jim Maclaine, and steal moments from our favourite films, a bit from East of Eden here, something from Francois Truffaut’s 'The 400 Blows' there."[2]

Puttnam offered the directing job to Michael Apted, who turned it down, Director Claude Watham was given the job when Puttnam was impressed with period detail of his TV movie Cider with Rosie.[4] He also liked the fact that Watham was not that interested in rock 'n roll, and thought Watham would provide an objective counterbalance to Puttnam and Connolly.[5]

Casting

editConnolly said that he cast David Essex, then starring in a West End production of Godspell, in an effort to make the selfish Jim MacLaine character more likeable, because Essex "was so good-looking and likeable an audience would forgive him anything."

Ringo Starr was cast as Mike after Connolly, who had never been to a holiday camp, consulted him and former Beatles road manager Neil Aspinall about their Butlins memories. Aspinall also helped to put together the camp band that appeared in the film.[2] Several roles were played by prominent musicians who had lived through the film's era, including Starr, Billy Fury, Keith Moon of the Who, and John Hawken of the Nashville Teens.

Filming

editFilming began on October 23, 1972, on the Isle of Wight, which still had a late-1950s look in the early 1970s.[2] Essex received a seven-week break from his Godspell role to film the picture.[6]

Puttnam clashed with Watham during filming, saying the director did not understand all the script's subtext. When Watham fell ill, Alan Parker directed for two days.[7]

U.S. Release

editThe film was initially acquired by Continental Releasing, a unit of the Walter Reade Organization, but after disappointing test engagements in Boston, Indianapolis, and Austin, they chose to shelve the film. Based on a well-received screening at Filmex in Los Angeles, programmer Jerry Harvey, partnering with Richard Chase and Kenneth Greenstone, created a small company, Mayfair Film Group, to take over distribution.

Soundtrack

editThe tie-in soundtrack to That'll Be the Day was released by Ronco and listed as a 'various artists' album rather than the official soundtrack. It spent seven weeks at the #1 position on the Official Albums Chart Top 50. However, beginning with the week ending 18 August 1973, all compilations listed as 'various artists' were removed from the chart, with only those billed as 'official soundtracks' (to films such as A Clockwork Orange and Cabaret) remaining,[8] causing That'll Be the Day to be excluded from the chart countdown.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

- Bobby Vee and The Crickets – "That'll Be the Day"

- David Essex – "Rock On" (featured in U.S. theatrical release only)

- Billy Fury – "A Thousand Stars"

- Billy Fury – "Long Live Rock"

- Billy Fury – "Get Yourself Together"

- Billy Fury – "That's Alright Mama"

- Billy Fury – "What Did I Say"

- Wishful Thinking – "It'll Be Me"

- Dion (erroneously credited to Dion and the Belmonts) – "Runaround Sue"

- The Everly Brothers – "Bye Bye Love"

- The Everly Brothers – "Devoted To You"

- The Everly Brothers – "Till I Kissed You"

- The Everly Brothers – "Wake Up Little Suzie" (not featured in film)

- The Platters – "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes"

- Big Bopper – "Chantilly Lace"

- Jerry Lee Lewis – "Great Balls of Fire"

- Little Richard – "Tutti Frutti"

- Danny and the Juniors – "At the Hop"

- Frankie Lymon – "Why Do Fools Fall In Love"

- Johnny Tillotson -"Poetry in Motion"

- Jimmie Rodgers – "Honeycomb"

- Larry Williams – "Bony Moronie"

- Del Shannon – "Runaway"

- Ritchie Valens – "Donna"

- Eugene Wallace – "Slow Down"

- Brian Hyland – "Sealed with a Kiss"

- Bobby Vee – "Take Good Care of My Baby" (not featured in film)

- Del Shannon – "Hats Off to Larry" (not featured in film)

- Bobby Darin – "Dream Lover"

- The Paris Sisters – "I Love How You Love Me"

- The Poni-Tails – "Born Too Late"

- Johnny and the Hurricanes – "Red River Rock"

- The Monotones – "The Book of Love"

- Bill Justis – "Raunchy"

- Johnny Preston – "Running Bear" (not featured in film)

- The Diamonds – "Little Darlin' "

- Ray Sharpe – "Linda Lu" (not featured in film)

- Lloyd Price – "(You've Got) Personality" (not featured in film)

- Bobby Vee and The Crickets – "Well All Right"

- Dante and the Evergreens – "Alley Oop" (not featured in film)

- Viv Stanshall – "Real Leather Jacket"

- Stormy Tempest ( Viv Stanshall ) – "What in the World"

- Buddy Knox - "Party Doll"

- Wolverine Cubs Jazz Band – "Weary Blues" (featured in the film but not on Soundtrack recording)

- Maurice Williams & The Zodiacs - "Stay" (featured in the film but not on Soundtrack recording)

(despite its enormous popularity this album has never had an official CD release in the UK)

Chart positions

edit| Chart (1973/74) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[16] | 9 |

| UK Albums Chart[17] | 1 |

Release

editThe film was a hit at the box office (by 1985 it had earned an estimated profit of £406,000).[1] Nat Cohen, who invested in the film, said it made more than 50% profit on top of its cost.[18] It was one of the most popular movies of 1973 at the British box office.[19]

Connolly said "At the time, I was astonished by its success. A sixth form drop out, who throws his school books into a river when he should be sitting his A-level history, writes poetry in the rain while hiring out deck chairs, and lets down just about absolutely everyone was hardly an obvious subject. But, on reflection, I can now see that there was nothing else like it at the time. And the music soundtrack was fantastic."[2]

Reception

editThe Los Angeles Times called it "a very special, strange and fascinating movie."[20]

According to Anne Billson in the Time Out Film Guide, the film was a "hugely overrated dip into the rock 'n' roll nostalgia bucket, ... " also commenting "Youth culture my eye: they're all at least a decade too old. But good tunes, and worth catching for Billy Fury's gold lamé act."[21]

Awards and nominations

editAt the 27th British Academy Film Awards in 1973, the film received two nominations. Rosemary Leach for Best Actress in a Supporting Role and David Essex for Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles.

Sequels

editEssex returned as Jim Maclaine the following year, in the 1974 sequel, Stardust, which continues the story into the early 1970s.

An independent radio drama recording project, That'll be the Stardust!, was released in 2008.[22] The story follows the musical journey of Jim Maclaine's son, Jimmy Maclaine Jr.

References

edit- ^ a b Alexander Walker, National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and Eighties, Harrap, 1985 p 79

- ^ a b c d e f Connolly, Ray (2017-09-30). "On the Origins of the Films That'll Be the Day and Stardust". rayconnolly.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ Yule p 85-86

- ^ In the Picture Sight and Sound; London Vol. 42, Iss. 2, (Spring 1973): 84.

- ^ Yule p 86

- ^ 'Day' Breaks With Starr Variety; Los Angeles Vol. 268, Iss. 11, (Oct 25, 1972): 30.

- ^ Yule p 87

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 50 | Official Charts Company". Official Charts.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 320. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Number 1 Albums – 1970s". The Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Ooh, you are awful, film men tell Tories. David Blundy. The Sunday Times (London, England), Sunday, 16 December 1973; pg. 5; Issue 7853. (939 words)

- ^ Harper, Sue (2011). British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press. p. 270. ISBN 9780748654260.

- ^ Looking Under a Rock Star: UNDER A ROCK Champlin, Charles. Los Angeles Times 30 Oct 1974: f1.

- ^ The TimeOut Film Guide, 3rd edition, 1993, p. 706

- ^ "Tony G. Marshall's "That'll be the Stardust!"". CosmicDwellings.com. 23 October 2014. Retrieved 2019-08-03.

Sources

edit- Yule, Andrew (1989). Enigma : David Puttnam, the story so far ... Sphere Books.