Texas City is a city in Galveston County, Texas, United States. Located on the southwest shoreline of Galveston Bay, Texas City is a busy deepwater port on Texas's Gulf Coast, as well as a petroleum-refining and petrochemical-manufacturing center. The population was 51,898 at the 2020 census,[3] making it the third-largest city in Galveston County, behind League City and Galveston. It is a part of the Houston metropolitan area. It is notable as the site of a major explosion in 1947 that demolished the port and much of the city.

Texas City, Texas | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "The city that would not die" | |

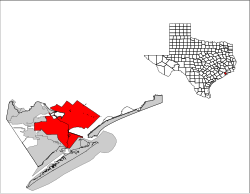

Location in Galveston County in the state of Texas | |

| Coordinates: 29°24′0″N 94°56′2″W / 29.40000°N 94.93389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Galveston |

| Founded | 1830s |

| Incorporated | 1911 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Mayor |

| • Mayor | Dedrick D. Johnson, Sr. |

| • City commission | Thelma Bowie Abel Garza, Jr. DeAndre' Knoxson Felix Herrera Dorthea Pointer Jami Clark |

| Area | |

• City | 186.58 sq mi (483.24 km2) |

| • Land | 66.27 sq mi (171.62 km2) |

| • Water | 120.31 sq mi (311.61 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 51,898 |

• Estimate (2022)[4] | 55,667 |

| • Rank | US: 719th TX: 69th |

| • Density | 840/sq mi (324.4/km2) |

| • Urban | 191,863 (US: 200th) |

| • Urban density | 1,760.5/sq mi (679.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC–6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 77510, 77539, 77568, 77590, 77591, 77592 |

| Area code | 409 |

| FIPS code | 48-72392 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1376420[2] |

| Website | texascitytx.gov |

History

editThree duck hunters in 1891 noted that a location along Galveston Bay, known locally as Shoal Point, had the potential to become a major port. Shoal Point had existed since the 1830s, when veterans of the Texas Revolution (1835–1836) were awarded land for their services. The name was applied to the community when a post office opened in 1878.[5] The duck hunters were three brothers from Duluth, Minnesota, named Benjamin, Henry, and Jacob Myers. After they returned to Duluth, they formed the Myers Brothers syndicate, convinced other investors to put up money to buy 10,000 acres (4,000 hectares) of Galveston Bay frontage, including Shoal Point. They renamed the area Texas City.

Founding

editBy 1893, the investors had formed the Texas City Improvement Company (TCIC), which plotted and filed the townsite plan. A post office opened in 1893 with Frank B. Davison appointed as the town's first postmaster, to serve about 250 people who had moved there from Minnesota and Michigan. TCIC also received permission from the federal government to dredge an eight-foot channel in the bay from Bolivar Roads (at the east end of Galveston Island) to serve Texas City.[6] In 1894, the channel was first used commercially. TCIC eventually dredged the channel to a 40-foot depth and extended the length of the port to 1.5 mi. TCIC also built a 4-mi railroad to the Texas City Junction south of town, where it connected to two other rail lines: Galveston, Houston and San Antonio and Galveston-Houston and Henderson.[7]

Despite these successes, the TCIC went bankrupt in 1897. Its assets were reorganized into two new companies: Texas City Company (TCC), and Texas City Railway Terminal Company (TCRTC). TCC acquired 3,000 city lots and provided water, gas, and electricity to the town. TCRTC operated the railroad. These companies were chartered on February 4, 1899.[6][7]

A grid of streets and avenues was laid out during the 1890s, and houses and other structures began to appear. The Davison Home, where the first childbirth in the town took place, was constructed between 1895 and 1897. As the TCIC, the TCC, and TCRTC expanded, urbanization expanded.

Permission was granted in the summer of 1900 to dredge the Texas City channel to a depth of 25 ft. The disastrous Galveston Hurricane of 1900 interrupted the project, washing the dredge ashore. However, the Texas City port remained open after the storm passed. Even before the channel dredging was complete, the first ocean-going ship, SS Piqua, arrived at the port from Mexico on September 28, 1904. Dredging was completed March 19, 1905, when the US government opened a customs house in Texas City.[6] Port growth progressed rapidly after this, from 12 ships in 1904, to 239 in 1910.[7]

Texas City Refining Company was chartered in 1908 to build a refinery adjacent to the port facility. For several years, it was the only Texas refinery capable of producing the byproducts wax and lubricating oil. This facility was later acquired and expanded by Texas oilman Sid Richardson.[6] Three more refineries soon followed, making Texas City a major port for deepwater shipping of Texas petroleum products to the Atlantic Coast.[7]

Texas City incorporated in 1911 with a mayor and commission form of government. It held its first mayoral election on September 16, choosing William P. Tarpey as mayor.[6]

The 2nd Division of the United States Army deployed to Texas City in 1913 to guard the Gulf Coast from incursions during the Mexican Revolution, essentially encamping nearly half of the nation's land military personnel there, due to the perceived double threat that the Mexican Revolution might spill over across the border or that the neighboring country might become a German ally in the incipient World War.

The military deployment also included the 1st Aero Division, and the Wright brothers trained over a dozen soldiers as military pilots, essentially turning Texas City into the birthplace of what became the United States Air Force, as the city claims at its monument of the birthplace of the Air Force at Bay Street City Park.[8] Speed and distance records were set by pilots trained and planes flying out of Texas City's impromptu military air base.

An August 1915 hurricane completely demolished the encampment. Nine soldiers were killed. Military leaders promptly moved the camp to San Antonio.[7]

In 1921, the Texas City Railway Terminal Company took over operations of the port facilities. Hugh B. Moore was named president of the company and began an ambitious program of expansions. He was credited with attracting a sugar refinery, a fig processing plant, a gasoline cracking plant, and a grain elevator. Also, more warehouses and tank farms were built to support this growth. By 1925, Texas City had an estimated population of 3,500 and was a thriving community with two refineries producing gasoline, the Texas City Sugar Refinery, two cotton compressing facilities, and even passenger bus service.[7]

The Great Depression and competition caused the sugar refinery to fail in 1930. Economic hard times afflicted the city for a few years until the oil business returned to expansion. Republic Oil Refinery opened a gasoline refinery in 1931. In 1934, Pan American Refinery (a subsidiary of Standard Oil Company of Indiana) began operating. Moore was able to win this refinery from the Houston Ship Channel because of Texas City's location nearer the Gulf of Mexico. By the end of the 1930s, Texas City's population had grown to 5,200.[7]

Seatrain Lines constructed a terminal at the Texas City port during 1939–1940. This was a specialized company that owned ships designed to carry railroad cars from Texas City to New York City on a weekly schedule. By 1940, Texas City was the fourth-ranked Texas port, exceeded only by Houston, Beaumont, and Port Arthur.[6]

Texas City Dike

editTexas City is home to the Texas City Dike, a man-made breakwater built of tumbled granite blocks in the 1930s, that was originally designed to protect the lower Houston Ship Channel from silting. The dike, famous among locals as being "the world's longest man-made fishing pier", extends roughly 5.2 mi (8 km) to the southeast into the mouth of Galveston Bay.

World War II impact

editProsperity and industrial expansion returned as the United States became more involved in World War II. Enemy submarines had almost completely stopped the shipment of petroleum products to friendly countries from the Middle East, South America, and Southeast Asia. Texas City refineries and chemical plants worked around the clock at full capacity to supply the war effort. Realizing that all of the world's tin smelters could no longer supply the US demand, Jesse H. Jones, head of the Defense Plant Corporation, decided to build the Texas City tin smelter. The government also funded construction of a petrochemical plant to make styrene monomer, a vital raw material for synthetic rubber. Monsanto Chemical Company contracted to operate the facility, which became the nucleus of an even larger petrochemical complex after the war. By 1950, the local population had reached 16,620.[7]

1947 Texas City disaster

editThe postwar prosperity was interrupted on the morning of April 16, 1947, when the French ship Grandcamp, containing ammonium nitrate fertilizer, exploded, initiating what is generally regarded as the worst industrial accident in United States history, the Texas City disaster. The fertilizer manufactured in Nebraska and Iowa was already overheating when stored at the Texas City docks. The blast devastated the Monsanto plant and offices, which were immediately across the slip from the Grandcamp, blew away the warehouses, showered shrapnel from the ship in all directions, and ignited a second ship, the S.S.High Flyer, docked at an adjacent slip. Released from its mooring by the blast, the High Flyer rammed a third ship, SS Wilson B. Keene, docked across the slip. Both ships also carried ammonium nitrate fertilizer and were ablaze. They, too, exploded. In all, the explosions killed 581 and injured over 5,000 people. The explosions were so powerful and intense that many of the bodies of the emergency workers who responded to the initial explosion were never accounted for. The entire Texas City and Port Terminal Fire departments were wiped out.[7]

The steel-reinforced concrete grain elevator was pockmarked with shrapnel and the drive shaft of the Grandcamp was embedded in the headhouse. The ship's anchor was hurled several miles away, where it was discovered embedded in the ground at the PanAmerican refinery. School children and townspeople who were attracted to the smoke also died, and entire blocks of homes near the port were destroyed. People in Galveston 14 miles (23 km) away were knocked to their knees. Surrounding chemical and oil tanks and refineries were ignited by the blast. At least 63 who died and were not able to be identified are memorialized in a cemetery in the north part of town. The Texas City disaster is widely regarded as the foundation of disaster planning for the United States. Monsanto and other plants committed to rebuilding, and the city ultimately recovered quite well from the accident. Numerous petrochemical refineries are still located in the same port area of Texas City. The city has often referred to itself as "the town that would not die," a moniker whose accuracy would be tested once again in the days surrounding Hurricane Ike's assault on the region early on September 13, 2008.

1987 Marathon Oil refinery hydrogen fluoride gas release

editOn October 30, 1987, a crane at the Marathon Oil refinery accidentally dropped its load on a tank of liquid hydrogen fluoride, causing a release of 36,000 pounds (16,000 kg) of hydrogen fluoride gas and requiring 3,000 residents to be evacuated.[9]

2005 BP explosion

editOn March 23, 2005, the city suffered another explosion in a local BP (formerly Amoco) oil refinery which killed 15 and injured 180.[10][11] In the U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB)'s final report on the accident, published in March 2007, they described the event as "one of the worst industrial disasters in recent U.S. history."[11] The BP facility in Texas City is the United States' third-largest oil refinery, employing over 2,000 people, processing 460,000 barrels (73,000 m³) of crude oil each day, and producing roughly 4% of the country's gasoline.

2008 Hurricane Ike

editEven in the widespread destruction throughout Galveston County caused by the wind and surge associated with Ike, Texas City was largely spared the devastation that other low-lying areas suffered. Texas City is mostly surrounded by a 17-mile-long (27 km) levee system that was built in the early 1960s following the devastating floods from Hurricane Carla in 1961. Together with pump stations containing several Archimedes' screws located at various places throughout the northeast periphery of the city adjoining Galveston, Dollar Bay, and Moses Lake, the levee and pump station system may well have saved the city from wholesale devastation at the hands of Ike's powerful tidal surge. Damage in the city was largely limited to that caused by Ike's powerful winds and heavy rains.

Beginning Sunday, September 14, 2008, the day after landfall, Texas City's high school football complex, Stingaree Stadium, was used as a staging and relocation area for persons evacuated by National Guard Black Hawk helicopters from nearby bayfront communities such as the Bolivar Peninsula and Galveston Island. Also, by the morning of Monday, September 15, the American Red Cross had opened a relief and material distribution center in the city.

The Texas City Dike was overtopped by a greater than 12-foot (3.7 m) storm surge when Hurricane Ike barreled through the region in the early-morning hours of Saturday, September 13, 2008. Although all buildings, piers, and the Dike Road were destroyed, the dike itself weathered the storm. The dike was closed for three years while the road and supporting facilities were rebuilt. It was reopened to traffic in September 2011.

Geography

editTexas City is 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Galveston and 37 miles (60 km) southeast of Houston.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 186.58 square miles (483.24 km2), of which 66.27 square miles (171.64 km2) is land and 120.31 square miles (311.60 km2), or 67.61%, is covered by water.[1]

Officially, the elevation of Texas City is 10 feet above sea level, though some areas are even lower. It was naturally vulnerable to flooding by hurricane storm surges and heavy rainstorms.

The land south and west of the city is flat coastal plain. A large part of this area to the south is marshland. Texas City is bounded on the north by Moses Lake, which is fed by Moses Bayou, a freshwater stream. The lake drains into Galveston Bay, which bounds the city on the east.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 2,509 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,534 | 40.9% | |

| 1940 | 5,748 | 62.6% | |

| 1950 | 16,620 | 189.1% | |

| 1960 | 32,065 | 92.9% | |

| 1970 | 38,908 | 21.3% | |

| 1980 | 41,201 | 5.9% | |

| 1990 | 40,822 | −0.9% | |

| 2000 | 41,521 | 1.7% | |

| 2010 | 45,099 | 8.6% | |

| 2020 | 51,898 | 15.1% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 55,667 | [4] | 7.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 2020 Census[3] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 18,822 | 36.27% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 14,189 | 27.34% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 158 | 0.3% |

| Asian (NH) | 680 | 1.31% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 34 | 0.07% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 224 | 0.43% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,675 | 3.23% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 16,116 | 31.05% |

| Total | 51,898 | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 51,898 people, 19,526 households, and 13,005 families residing in the city.[16] There were 21,493 housing units.

2000 census

editAs of the 2000 census, there were 41,521 people, 15,479 households, and 10,974 families resided in the city. The population density was 665.7 inhabitants per square mile (257.0/km2). The 16,715 housing units averaged 268.0/sq mi (103.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 60.75% White, 27.47% African American, 0.50% Native American, 0.88% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 8.23% from other races, and 2.12% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 20.52% of the population.

Of the 15,479 households, 33.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.6% were married couples living together, 17.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.1% were not families. About 24.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.62 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the city, the population was distributed as 26.7% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 13.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,963, and for a family was $42,393. Males had a median income of $36,463 versus $24,754 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,057. About 12.0% of families and 14.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.5% of those under age 18 and 11.2% of those aged 65 or over.

Racial groups

editThe Hispanic and Latino population's percentage of the overall population of Texas City had increased to 29.9% in 2017 from 27% in 2010, and by then the city had a Hispanic supermarket and other businesses catering to Hispanics. The African-American percentage had declined to 28% in 2017 from 30.8% in 2010.[17]

Economy

editThe Texas City economy has long been based on heavy industry, particularly shipping at the Port of Texas City, as well as petroleum and petrochemical refining.[18] The Texas City Industrial Complex is a leading center of the petrochemical industry. Within this complex, the Galveston Bay Refinery operated by Marathon is the second-largest petroleum refinery in Texas and third-largest in the United States.[19][20] The Port of Texas City became the third-leading port in Texas by tonnage and ninth in the nation.[7][21] In recent decades, the city's planners have made efforts to diversify the economy into tourism, health care, and many other sectors.[18] As early as 1974, Texas City was placed on the top-ten list for the EPA superfund. Outdated practices for the disposal of toxic waste have continued there for years.

The Port of Texas City, operated by the Port of Texas City / Texas City Terminal Railway, is the eighth-largest port in the United States and the third-largest in Texas, with waterborne tonnage exceeding 78 million net tons. The Texas City Terminal Railway Company provides an important land link to the port, handling over 25,000 carloads per year. The Port of Texas City's success as a privately owned port has been aided by its shareholders, the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroads, whose connections allow for expeditious interchange of their traffic.

The Galveston County Juvenile Justice Department Jerry J. Esmond Juvenile Justice Center is in Texas City.[22] Prisoners there attend the Dickinson Independent School District.[23]

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice maintains the Young Medical Facility Complex for females in Texas City.[24] Young opened in 1996 as the Texas City Regional Medical Unit.[25]

Arts and culture

editIn 1928, the city dedicated a room in city hall to form a municipal library, operated by the Texas City Civic Club. In 1947, city hall received damage from the Texas City explosion; it was later demolished. In 1948, the library moved to a former house. In 1964, the library moved into its current building. In 1984, the Moore Memorial Public Library was expanded to 21,000 square feet (2,000 m2).[26]

The Texas City Museum includes the Galveston County Model Railroad Club exhibit.[27]

Parks and recreation

editThe city operates 42 parks, some of which are part of the Great Texas Coastal Birding Trail.[28]

The Texas City Prairie Preserve is a 2,300-acre (930-hectare) nature preserve located on the shores of Moses Lake opposite the city. The terrain of the preserve includes prairie and wetland habitats. The preserve includes 40 acres (16 hectares) of public-access areas, including campsites. The remainder of the preserve is available for tours, including boardwalk access through the marshes.[29]

The Bay Street Park is a 45-acre (18-hectare) property near the bay and the levee. Part of the park commemorates the Aero Squadron, one of the first U.S. Army air squadrons and a precursor to the modern Air Force. The rest of the park features wilderness trails and family entertainment areas.[30]

Nessler Park is a 55-acre (22-hectare) property used for community events such as the annual "Music Fest by the Bay". Other large city parks include Carver Park, Godard Park, and Holland Park.

The centerpiece of Texas City's Heritage Square historical district is the former residence of one of the city's fathers, Frank B. Davison. The Victorian-styled Davison Home was completed in 1897.

Education

editPrimary and secondary schools

editPublic schools

editMost of Texas City is served by the Texas City Independent School District, which has four elementary schools for grades K–4: Kohfeldt Elementary, Roosevelt-Wilson Elementary, Heights Elementary, and Guajardo Elementary. The TCISD intermediate school, Levi Fry Intermediate, provides for fifth and sixth graders, and one TCISD middle school, Blocker Middle School, provides for seventh and eighth graders. Texas City High School serves the TCISD portion of Texas City.

Other portions are a part of the Dickinson Independent School District.

Some were previously in the La Marque Independent School District. On December 2, 2015, Texas Education Agency (TEA) Commissioner Michael Williams announced that the Texas City Independent School District would absorb the La Marque district effective July 1, 2016.[31]

Private schools

editOur Lady of Fatima School, a Roman Catholic elementary school operated by the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, is in Texas City.[32]

Colleges and universities

editTexas City is served by the College of the Mainland, which is located in Texas City.[33]

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editThe major freeway serving the area is the Gulf Freeway, part of Interstate 45, which connects Texas City with Galveston and Houston. Texas State Highway 146 locally connects Texas City with other Galveston Bay Area communities on the shoreline. Texas Loop 197 combines with Highway 146 to form a ring around the city, providing access to the city's major areas.[34]

Police

editIn 2008, civilian code-enforcement officers were replaced with police officers because residents tended to ignore civilian officials.[35]

Notable people

edit- Chris Ballard, NFL Colts General Manager

- Charles Brown, blues singer and pianist

- John Carona, politician

- Frank B. Davison, city pioneer who built Davison home, now a museum

- George Ducas, country music singer

- Charlie Dupre, former NFL player

- L.G. Dupre, former NFL player

- Ben Emanuel, American football player

- D'Onta Foreman, professional football player

- Andy Hassler, professional baseball player

- Johnny Lee, country music singer

- Edi Patterson, actress on The Righteous Gemstones

- Stone Phillips, television reporter and correspondent

- Ron Raines, actor

- Mary Simpson, one of the first women to be ordained a priest by the American Episcopal Church

- Donna Wick, author and broadcaster

In popular culture

edit- The 2021 movie Red Rocket is set in Texas City.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Texas City, Texas

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2022". United States Census Bureau. February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ The Historical Marker Database. "Shoal Point and Half Moon Shoal Lighthouse."[1]

- ^ a b c d e f Wheaton, Grant. "Annals of Texas City." Retrieved March 2, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Priscilla Myers Benham, "TEXAS CITY, TX," Handbook of Texas Online. Accessed February 29, 2012 [2]. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ "Bay Street Park". Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ Nordin, John. "Technically Speaking: Hydrogen Fluoride – Spilled and Tested". The First Responder (Newsletter). Aristatek, Inc. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ Goodwyn, Wade (May 6, 2010). "Previous BP Accidents Blamed On Safety Lapses". NPR. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ a b U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (March 20, 2007). "INVESTIGATION REPORT REFINERY EXPLOSION AND FIRE" (PDF). U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. p. 17. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

Explosions and fires killed 15 people and injured another 180

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/ [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Eastburn, Kathryn (April 13, 2019). "Hispanic-Latino population on the rise in Texas City". Galveston Daily News. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "Economic Development". City of Texas City. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Refineries* Operable Capacity". Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration. July 2008.

- ^ Regester, Michael; Larkin, Judy (2008). Risk Issues and Crisis Management in Public Relations: A Casebook of Best. Kogan Page. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7494-2393-3.

- ^ "U.S. Port Ranking by Cargo Volume 2004". American Association of Port Authorities. 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010.

- ^ Reynolds, Jennifer (November 25, 2022). "Galveston County juvenile detention center full despite lower crime rates". Galveston County Daily News. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "Esmond Juvenile Justice Center Residential School Comprehensive Needs Assessment for the Development of the Campus Improvement Plan 2013-14" (PDF). Dickinson Independent School District. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "YOUNG MEDICAL FACILITY COMPLEX (GC) Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ^ Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Turner Publishing Company, 2004. 51. ISBN 1-56311-964-1, ISBN 978-1-56311-964-4.

- ^ "About Us Archived September 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine." Moore Memorial Public Library. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ^ Texas City Museum. Retrieved March 6, 2011

- ^ "Parks Locations". Texas City. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ "Gulf Coast Bird Observatory: Texas City Prairie Preserve" (PDF). Gulf Coast Bird Observatory. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ "Bay Street Park". Texas City. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ Daughtry, Shannon. "TEA: Texas City ISD to annex La Marque ISD ." The Galveston County Daily News. Wednesday December 2, 2015. Retrieved on January 12, 2016. "Texas City ISD will annex La Marque ISD into its school district beginning in the 2016-17 school year."

- ^ "Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston / School Page / Our Lady of Fatima School - Texas City". diogh.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Texas Education Code, Section 130.174, "College of the Mainland District Service Area".

- ^ "Economic Development". City of Texas City. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2010.

- ^ Rice, Harvey. "POLICING THE NEIGHBORHOOD / ARRESTING BLIGHT ON PATROL / Texas City is using a team of officers to put teeth in city code enforcement Archived May 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Chronicle. August 27, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2008. B1MetFront

External links

edit- City of Texas City – Official Website

- Historic Photos from the Moore Memorial Public Library, Texas City, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Texas City from the Handbook of Texas Online

- "Texas City Markers." The Historical Markers Database. Retrieved March 11, 2012 Archived April 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Wheaton, Grant. "Annals of Texas City Port of Opportunity."[3]