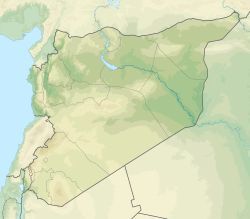

Terqa is the name of an ancient city discovered at the site of Tell Ashara on the banks of the middle Euphrates in Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria, approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the modern border with Iraq and 64 kilometres (40 mi) north of the ancient site of Mari, Syria. Its name had become Sirqu by Neo-Assyrian times.

| |

| Location | Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Deir ez-Zor Governorate |

| Coordinates | 34°55′24″N 40°34′10″E / 34.92333°N 40.56944°E |

Location

editTerqa was located near the mouth of the Khabur river, thus being a trade hub on the Euphrates and Khabur rivers.[1] To the south was Mari. To the north was Tuttul (Tell Bi'a) near the mouth of the Balikh river. Terqa ruled a larger hinterland. Terqa was always second to Mari, as the valley could hold only one political main center. The region was dominated by arid/non-irrigable land, with a characteristic relationship to water resources and land exploitation.[2]

Amorite tribal groups included the Khaeans and Suteans south of Mari.

Terqa would politically play to role as a minor provincial center with a governor or a petty local kingdom.

History

editLittle is yet known of the early history of Terqa, though it was a sizable entity even in the Early Dynastic period. The principal god of Terqa was Dagan.

Early Bronze

editIn the late Early Bronze III-IV, Ebla and Mari competed for hegemony in the Euphrates region and Terqa became a contested town before the Akkadian Empire took control.

Terqa was an urban center with a massive defensive wall, but a provincial city under the political control of Mari.[3]

In Early Bronze IVB, the Ur III dynasty had governors at Mari, which may have included Terqa as well.

Middle Bronze

editIn the early 2nd millennium BC it was under the control of Shamshi-Adad (c. 1808–1776 BC) of the Amorite Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, followed by Mari beginning with the reign of the Amorite ruler Yahdun-Lim one of whose year names was "Year in which Yahdun-Lim built the city walls of Mari and Terqa". Control by Mari continued into the time of Zimri-Lim (c. 1775 to 1761 BC). One year name of Zimri-Lim was "Year in which Zimri-Lim offered a great throne to Dagan of Terqa".

When not ruled by a king, Terqa was a vassal city-state ruled by a governor subordinate to Mari. Kibri-Dagan, governor of Terqa, under Zimri-Lim.[4][5]

In Mari Letter ARM 13.110 concerns the Temple of Dagan. Letter by Kibri-Dagan governor of Terqa to the king: “My lord wrote me about the 10 minas of silver that offenders settled to me: This is silver must arrive quickly to be processed for the works on the throne of Dagan.[6]

Mari/Terqa interacted over the wide steppes in Syria with their herdsmen coming in contact with the herdsmen from Qatna,[7] by the way of Palmyra.

In a major change of events, the 'Fall of Mari' came when Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1792-1750 BC) attacked his former ally, Zimri-Lim of Mari (r. 1775 to 1761 BC). With Mari destroyed power in the Middle Euphrates shifted to Terqa.

Terqa became the leading city of the kingdom of Khana after the decline of Babylon.

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Yapah-Sumu | circa 1700 | |

| Isi-Sumu-Abu | ||

| Yadikh-Abu | Contemporary of Samsu-iluna of Babylon, 7 year names known | |

| Kastiliyasu | 4 year names known | |

| Sunuhru-Ammu | 4 year names known | |

| Ammi-Madar | 16th century | 1 year name known |

| ... several other kings omitted ...[8] |

Late Bronze

editIn mid-15th century BC, Terqa came under the control of the Mitanni kingdom. Kings Sinia and Qiš-Addu ruled during the time of the Mitanni kings Sausadatra, Sa’itarna and Parattarna.

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sinia (Qiš-Addu served as governor) | ||

| Qiš-Addu (under Parattarna of Mitanni) | mid-15th century | |

| Iddin-Kakka | late 15th century | |

| Isar-Lim | late 15th century | 1 year name known |

| Yaggid-Lim (Iggid-Lim, son of Isar-Lim) | ||

| Isih-Dagan | 1 year name known | |

| Hammurapih | 3 year names known | |

| Parshatatar | Mitanni king |

According to Podany (2014),

- "The kings who called themselves “king of the land of Hana” and who were not associated with the names of Mittanian rulers (i.e., those other than Sinia and Qiš-Addu [both mid-15th century]) ruled for at least seven and perhaps as many as eight generations. The first four passed the throne from father to son: Iddin-Kakka [late 15th century] → Išar-Lim → Iggid-Lim → Isih-Dagan [early 14th century]."[9]

Iron Age

editLater, it fell into the sphere of the Kassite dynasty of Babylon and eventually the Neo-Assyrian Empire. A noted stele of Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta II (890 to 884 BC) was found near Terqa.[10]

Archaeology

editThe main site is around 20 acres (8.1 ha) in size and has a height of 60 feet (18 m). Two thirds of the remains of Terqa are covered by the modern town of Ashara, which limits the possibilities for excavation.

The site was briefly excavated by Ernst Herzfeld in 1910.[11] In 1923, 5 days of excavations were conducted by François Thureau-Dangin and P. Dhorrne.[12]

From 1974 to 1986, Terqa was excavated for 10 seasons by a team from the International Institute for Mesopotamian Area Studies including the Institute of Archaeology at the University of California at Los Angeles, California State University at Los Angeles, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Arizona and the University of Poitiers in France. The team was led by Giorgio Buccellati and Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati.[13][14][15] The final reports from these excavations have been released over time.[16][17][18] The same team also excavated the nearby (5 kilometers north) 4th Millennium site of Tell Qraya which they viewed as the probably source for the settlement of Terqa.[19] After 1987, a French team led by Olivier Rouault of Lyon University took over the dig and continued to work there until local conditions deteriorated around 2010.[20][21][22]

There are 550 cuneiform tablets from Terqa held at the Deir ez-Zor Museum.[23]

Notable features found at Terqa include

- A city wall, consisting of three concentric masonry walls, 20 feet (6.1 m) high and 60 feet (18 m) in width, fronted by a 60-foot-wide (18 m) moat. The walls encompass a total area of around 60 acres (24 ha) with a perimeter of around 1800 meters. Based on ceramic and radiocarbon dating the inner wall was built c. 2900 B.C., the middle wall c. 2800 BC and the outer wall c. 2700 BC and the fortifications were in use until at least 2000 BC.

- A temple to Ninkarrak dating at least as old as the 3rd millennium. The temple finds included Egyptian scarabs.[24]

- The House of Puzurum, where a large and important archive of Khana Period tablets, mostly contracts for purchases of land and houses in the Terqa area, were found.[25] The location produced a number of sealing (on tablets, tags, and bullae). Many of the tablets are dated to the time of ruler Yadib-Abu. A few Mari Period sealings were found elsewhere at the site.[26]

Temple to Ninkarrak

editNinkarrak was the ancient goddess of healing. Her temple was identified based on a tablet with a list of offerings which starts with her name, and by seals mentioned the goddess. Thousands of beads made out of precious materials such as agate, carnelian, and lapis lazuli were found here.[27]

Archaeologists also found a number of small bronze figurines of dogs inside the temple as well. Dogs were the animals sacred to Ninkarrak.[28]

A ceremonial axe and a scimitar with a devotional inscription mentioning Ninkarrak, both bronze, were also found.

Early occupation of the structure has been dated to roughly the same period as the reigns of three kings of Terqa. The earliest of them was Yadikh-abu, a contemporary of Samsuiluna of Babylon, defeated by the latter in 1721 BCE.[29] Kashtiliash, and Shunuhru-ammu also ruled during this period. The temple was remodeled multiple times.

The Egyptian scarabs found in the temple of Ninkarrak represent the easternmost known example of such objects in a sealed deposit dated to the Old Babylonian period.[30] They are attributed to around 1650-1640 BC, or the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt. The hieroglyphs inscribed on them are regarded as "poorly executed and sometimes misunderstood," indicating Levantine, rather than Egyptian, origin. Similar scarabs are also known from Byblos, Sidon and Ugarit.[31]

Temple to Lagamal

editLagamal was a Mesopotamian deity worshiped chiefly in Dilbat, but it was prominent in Terqa as well, and also in Susa. This was a deity associated with the underworld.[32]

In the majority of known sources Lagamal is a male deity, but it was regarded as a goddess rather than a god in Terqa.[33]

Icehouse

editThe oldest attested ice house (building) in the world may have been built in Terqa. It is recorded in a cuneiform tablet from c. 1780 BC that Zimri-Lim, the King of Mari ordered such a construction in Terqa, "which never before had any king built."[34]

Trade

editEvidence of trade contacts with the Indus valley has been found here. Archaeologist Giorgio Buccellati found cloves, an important spice, in a burned-down house which was dated to 1720 BC.[35]

- "In the pantry of a house belonging to an individual named Puzurum, dated by tablets to c. 1700 BCE or slightly thereafter, were found 'a handful of cloves ... well preserved in a partly overturned jar of a medium size'."[36][37]

Since this house was described as being of a medium size, it seems that, at that time, cloves were already accessible to the common people of Terqa.

Cloves are native to the Molucca Islands off the coast of Indonesia, and were extensively used in ancient India. This was the first evidence of cloves being used in the west before Roman times. The discovery was first reported in 1978.[38][39][40]

Genetics

editAncient mitochondrial DNA from freshly unearthed remains (teeth) of 4 individuals deeply deposited in slightly alkaline soil of ancient Terqa and Tell Masaikh (ancient Kar-Assurnasirpal, located on the Euphrates 5 kilometres (5,000 m) upstream from Terqa) was analysed in 2013. Dated to the period between 2.5 Kyrs BC and 0.5 Kyrs AD the studied individuals carried mtDNA haplotypes corresponding to the M4b1, M49 and M61 haplogroups, which are believed to have arisen in the area of the Indian subcontinent during the Upper Paleolithic and are absent in people living today in Syria. However, they are present in people inhabiting today’s India, Pakistan, Tibet and Himalayas.[41] A 2014 study expanding on the 2013 study and based on analysis of 15751 DNA samples arrives at the conclusion, that "M65a, M49 and/or M61 haplogroups carrying ancient Mesopotamians might have been the merchants from India".[42]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Buccellati (1992) Ebla and the Amorites

- ^ Buccellati 1992:88

- ^ Buccellati 1992:94

- ^ Letters from Mari, ARM 3.42

- ^ [1] Correspondance de Kibri-Dagan

- ^ Ilya Arkhipov (2019) Zimri-Lim offers a throne to Dagan of Terqa, in J. Evans, E. Roßberger, P. Paoletti (eds.), Mesopotamian Temple Inventories in the Third and Second Millennia BCE: Integrating Archaeological, Textual, and Visual Sources. Proceedings of a conference held at the LMU Centre for Advanced Studies, November 14–15, 2016. Gladbeck, p. 131-137.

- ^ Buccellati 1992:94

- ^ Amanda H. Podany (2014), Hana and the Low Chronology. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 73, No. 1 (April 2014), pp. 49-71. (see Table I)

- ^ Amanda H. Podany (2014), Hana and the Low Chronology. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 73, No. 1 (April 2014), pp. 49-71

- ^ H. G. Güterbock, A Note on the Stela of Tukulti-Ninurta II Found near Tell Ashara, JNES, vol. 16, pp. 123, 1957

- ^ E. Herzfeld, Hana et Mari, RA, vol. 11, pp. 131-39, 1910

- ^ François Thureau-Dangin and P. Dhorrne, Cinq jours de fouilles à 'Ashârah (7-11 Septembre 1923), Syria, vol. 5, pp. 265-93, 1924

- ^ TextPlates G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 1: General Introduction and the Stratigraphic Record of the First Two Seasons, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol 1, no.3, pp. 73-133, 1977

- ^ [2] G. Buccellati and M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 6: The Third Season: Introduction and the Stratigraphic Record, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, vol 2, pp. 115-164, 1978

- ^ [3] Giorgio Buccellati, Terqa Preliminary Reports 10: The Fourth Season: Introduction and Stratigraphic Record, Undena, 1979, ISBN 0-89003-042-1

- ^ [4] Olivier Rouault, "Terqa Final Reports No. 1: L'Archive de Puzurum", BM 16, Undena, 1984 ISBN 0-89003-103-7

- ^ [5] Olivier Rouault, "Terqa Final Reports No. 2: Les textes des saisons 5 à 9", BM 29, Undena, 2011 ISBN 978-0-9798937-1-1

- ^ [6] Federico Buccellati, "Terqa Final Reports 3: Cloves and paleobotany, scarabs and beads, plaques and figurines", BM 31, Undena, 2020 ISBN 978-0-9798937-6-6

- ^ [7] Daniel Shimabuku, "Terqa Final Reports No. 2: Tell Qraya on the Middle Euphrates", BM 32, Undena, 2020 ISBN 978-0-9798937-7-3

- ^ Olivier Rouault, Mission archéologique à Ashara-Terqa (Syrie) : note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2005, S.l., 2004

- ^ Olivier Rouault, Projet Terqa et sa région (Syrie) : mission archéologiques à Terqa et à Masaïkh, recherches historiques et épigraphiques ; rapport final de la saison 2001 ; note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2003, S.l., 2002

- ^ Olivier Rouault, Projet Terqa et sa région (Syrie) : recherches à Terqa et dans la région, année 2001 ; note de synthèse sur les opérations projetées en 2002, S.l., 2001

- ^ [8] Buccellati, G., "On the distribution of epigraphic finds at Terqa", AAAS 26-7, pp. 102-106, 1987(2

- ^ [9] R. M. Liggett, Ancient Terqa and its Temple of Ninkarrak: the Excavations of the Fifth and Sixth Seasons, Near East Archaeological Society Bulletin, NS 19, pp. 5-25, 1982; see now also: A. Ahrens, The Scarabs from the Ninkarrak Temple Cache at Tell ’Ašara/Terqa (Syria): History, Archaeological Context, and Chronology, Egypt and the Levant 20, 2010, 431-444

- ^ Podany, Amanda H., In the 3700 year footsteps of a king, a barber, and a slave, Aeon, February 9, 2023

- ^ kelly-buccellati, marilyn. "Sealing Practices at Terqa" in Insight through images. Studies in Honor of E. Porada. ed. by Marilyn Kelly-buccellati. - Malibu: Undena publ. 1986. X, 268, 64 s., ill., kt., portr. (= bibliotheca mesopotamica. 21.), 1986

- ^ Ahrens, Alexander (2010). "THE SCARABS FROM THE NINKARRAK TEMPLE CACHE AT TELL 'AŠARA/TERQA (SYRIA): HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT, AND CHRONOLOGY". Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant. 20. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: 431–444. doi:10.1553/AEundL20s431. ISSN 1015-5104. JSTOR 23789950. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Liggett, Renata M. (1982). "Ancient Terqa and its temple of Ninkarrak: The Excavations of the Fifth and Sixth Seasons". Near Eastern Archaeology Society Bulletin. p. 14

- ^ Liggett, Renata M. (1982). "Ancient Terqa and its temple of Ninkarrak: The Excavations of the Fifth and Sixth Seasons". Near Eastern Archaeology Society Bulletin. p.23

- ^ Ahrens, Alexander (2010). "THE SCARABS FROM THE NINKARRAK TEMPLE CACHE AT TELL 'AŠARA/TERQA (SYRIA): HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT, AND CHRONOLOGY". Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant. 20. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: 431–444. doi:10.1553/AEundL20s431. ISSN 1015-5104. JSTOR 23789950. Retrieved 2021-08-02. p. 431.

- ^ Ahrens, Alexander (2010). "THE SCARABS FROM THE NINKARRAK TEMPLE CACHE AT TELL 'AŠARA/TERQA (SYRIA): HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT, AND CHRONOLOGY". Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant. 20. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: 431–444. doi:10.1553/AEundL20s431. ISSN 1015-5104. JSTOR 23789950. Retrieved 2021-08-02. p. 435.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7.

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni; Marchetti, Nicoló (2019). "A babylonian official at Tilmen Höyük in the time of king Sumu-la-el of Babylon". Orientalia. 88 (1): 1–36. ISSN 0030-5367. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ Stephanie Dalley (1 May 2002). Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. Gorgias Press. p. 91. ISBN 9781931956024.

- ^ [10] Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa: The First Eight Seasons, Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 33(2), 1983, 47-67

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (1997), Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. A&C Black publishers, p. 269

- ^ Buccellati 1983:19

- ^ Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, The Terqa Archaeological Project: First Preliminary Report., Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 27-28, 1977-78, 71-96

- ^ Buccellati, G., M. Kelly-Buccellati, Terqa: The First Eight Seasons, Les Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes 33(2), 1983, 47-67

- ^ Terqa - A Narrative terqa.org

- ^ Witas, Henryk W.; Jacek Tomczyk; Krystyna Jędrychowska-Dańska; Gyaneshwer Chaubey & Tomasz Płoszaj (2013) "mtDNA from the Early Bronze Age to the Roman Period Suggests a Genetic Link between the Indian Subcontinent and Mesopotamian Cradle of Civilization"; PLOS ONE, September 11, 2013. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073682.

- ^ Palanichamy, Malliya gounder; Mitra, Bikash; Debnath, Monojit; Agrawal, Suraksha; Chaudhuri, Tapas Kumar; Zhang, Ya-Ping (9 October 2014). "Tamil Merchant in Ancient Mesopotamia". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e109331. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9331P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109331. PMC 4192148. PMID 25299580.

References

edit- [11] G. Buccellati, The Kingdom and Period of Khana, Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 270, pp. 43–61, 1977

- [12] Giorgio Buccellati, "Terqa Preliminary Report 2: A Cuneiform Tablet of the Early Second Millennium B.C", Syro-Mesopotamian Studies 1, pp. 135–142, 1977

- M. Chavalas, Terqa and the Kingdom of Khana, Biblical Archaeology, vol. 59, pp. 90–103, 1996

- A. H. Podany, A Middle Babylonian Date for the Hana Kingdom, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 43/45, pp. 53–62, (1991–1993)

- J. N. Tubb, A Reconsideration of the Date of the Second Millennium Pottery From the Recent Excavations at Terqa, Levant, vol. 12, pp. 61–68, 1980

- A. Soltysiak, Human Remains from Tell Ashara - Terqa. Seasons 1999-2001. A Preliminary Report, Athenaeum, 90, no. 2, pp. 591–594 2002

- J Tomczyk, A Sołtysiak, Preliminary report on human remains from Tell Ashara/Terqa. Season 2005, Athenaeum. Studi di Letteratura e Storia dell’Antichità, vol. 95 (1), pp. 439–441, soo7