Teiaiagon was an Iroquoian village on the east bank of the Humber River in what is now the York district of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was located along the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail. The site is near the current intersection of Jane Street and Annette Street, at which is situated the community of Baby Point.

The name means "It crosses the stream."[1]

History

editPercy Robinson's Toronto During the French Regime shows Teiaiagon as being a jointly occupied village of Seneca and Mohawk. Helen Tanner's Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History describes Teiaiagon as a Seneca village around the years 1685-1687, although it existed before that time, and as a Mississauga village around 1696.[2]

Étienne Brûlé passed through Teiaiagon in 1615.[3] The village was on an important route for the developing fur trade industry,[4] and it was also "surrounded by horticultural fields".[5] It was said to be about "a day's journey from the Toronto Lake, our present Lake Simcoe".[6]

On November 18, 1678, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle departed Fort Frontenac for Niagara in a brigantine with a crew including La Motte and the Récollet missionary Louis Hennepin, following the north shore of Lake Ontario to mitigate the effects of a storm. The ship was grounded three times, forcing the crew to stop at the mouth of the Humber River on November 26. The surprised inhabitants of the village "were hospitable and supplied them with provisions".[7] On December 5, the ship set off after being cut out of the ice with axes.[7] Before departing, "La Motte's men bartered their commodities with the natives" for corn.[8]

Hennepin and others have recorded that the village was inhabited by as many as 5,000 people and had 50 long houses. La Salle camped at Teiaiagon several other times, once in the summer of 1680, and "perhaps twice in 1681" during his expeditions.[5] There was a 10-acre (40,000 m2) burial ground located in the central part of the village.

The Senecas left the village, either pushed out by, or voluntarily for, the Mississaugas by 1701. With the removal of the Iroquois from southern Ontario by the Mississaugas,[9] the Anishinaabe and French trade began to flourish in the region shortly after the Great Peace of Montreal of 1701. Associated with this trade, there was a very small French garrison or Magasin Royal located near the site of Teiaiagon from 1720 to 1730. In 1730, the French garrison was located downriver of the site. A store was later built at the mouth of the Humber in 1750 and Fort Rouillé soon after, east of the Humber.

The Mississaugas did not live at the site of the village of Teiaiagon,[10] but had a village located across the Humber River, on the west bank of the river, near Old Mill Road and Bloor Street, from 1788-1805. James Bâby from Detroit in 1816 acquired the land now called Baby Point and only had orchards located on the site of Teiaiagon. The site was relatively undisturbed as it was not farmed. The Teiaiagon area was acquired by the government for a military fortress and army barracks, but then was sold to Robert Home Smith, who began developing the Baby Point subdivision in 1912. In 1949, at the south-west corner of Baby Point Road and Baby Point Crescent, a plaque was erected, briefly mentioning "Taiaiagon."

Cartography

editPossibly because early European explorers had difficulty in transcribing First Nations names into European orthographic systems, numerous spelling variations exist. These include Taiaiako'n, Taiaiagon, Teyeyagon, and Toioiugon.

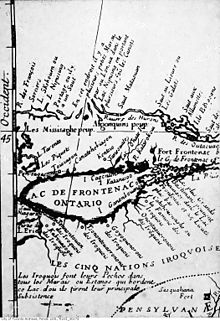

The name "Teiaigon" appears on a 1688 map of New France drawn by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin based on "sixteen years' of observation of the author".[11] It was indicated to be on the eastern side of a small bay, from which a portage route led to the west branch of Lake Taronto.

Archeology

editExcavations at Baby Point were first conducted in the late nineteenth century. Records from that excavation have been lost, though it is known that they revealed "traces of palisade walls".[5] In the late 1990s and early 2000s another excavation, conducted as a result of installation of a natural gas line to the residential neighbourhood, discovered the burial plots of two Seneca women, which were dated to the 1680s.[5] One of the women was buried with a moose antler comb engraved with a rattlesnake-tailed panther, "possibly representing Mishipizheu",[12] which morphs into a bear. The other woman was buried with three brass rings and a carved moose antler comb depicting "two human figures wearing European-style clothes flanking an Aboriginal figure".[12] Another burial plot on Baby Point was found in 2010 when a house was being renovated. Artifacts were studied and a ceremonial reburial took place.[13]

Just north of the site, in today's Magwood Park, is "Thunderbird Mound", which is believed to be an ancient burial mound.[13] The site has not been studied for its archaeology. The site is considered threatened by erosion and pedestrian traffic by the Taiaiako'n Historical Preservation Society.[14]

Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario

editBy the late 1660s various Five Nation Iroquois had established seven villages along the shores of Lake Ontario where trails led off into the interior. In addition to Teiaiagon at the mouth of the Humber River, the following settlements have been identified by historian Percy James Robinson:[15]

- Ganneious - on the site of present-day Napanee

- Kente - on the Bay of Quinte

- Kentsio - on Rice Lake

- Ganaraske - on the site of present-day Port Hope

- Ganatsekwyagon - at the mouth of the Rouge River

- Quinaouatoua (or Tinawatawa) - Near modern-day Hamilton

See also

editReferences

edit- Eid, Leroy V. (Autumn 1979). "The Ojibwa-Iroquois War: The War the Five Nations Did Not Win". Ethnohistory. 26 (4). Duke University Press: 297–324. doi:10.2307/481363.

- Groves, Tim. The Village of Taiaiako'n/Teiaiagon.

- Lizars, Kathleen Macfarlane (1913). The Valley of the Humber. Global Heritage Press (2010), William Briggs (1913). ISBN 978-1-926797-14-4.

- Schmalz, Peter S. (1991). The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2736-9. LCCN 94137640. OCLC 21910492.

- Tanner, Helen Hornbeck; Hast, Adele; Peterson, Jacqueline; Surtees, Robert J.; Pinther, Miklos (1987). Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2056-8.

- Ronald F. Williamson, ed. (2008). Toronto: A Short Illustrated History of its first 12,000 Years. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55277-007-8.

Notes

edit- ^ Robinson, Percy J. (2019). Toronto During the French Regime. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 243. ISBN 9781487584504. Retrieved Feb 18, 2022.

- ^ Tanner 1987: 33

- ^ Teiaiagon

- ^ Williamson 2008: 50

- ^ a b c d Williamson 2008: 51

- ^ Lizars 1913: 17

- ^ a b Lizars 1913: 24

- ^ Lizars 1913: 25

- ^ Eid 1979

- ^ Lizars 1913: 32

- ^ Lizars 1913: 16

- ^ a b Williamson 2008: 52

- ^ a b "Archaeological Significance | Baby Point Heritage Foundation". Baby Point Heritage Foundation. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ "Magwood Park". Taiaiako'n Historical Preservation Society. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Marcel, C.M.W. "Iroquois origins of modern Toronto". counterweights. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

43°39′22″N 79°29′43″W / 43.65601320416743°N 79.49539641090861°W