Tefnut (Ancient Egyptian: tfn.t; Coptic: ⲧϥⲏⲛⲉ tfēne)[1][2] is a deity in Ancient Egyptian religion, the feminine counterpart of the air god Shu. Her mythological function is less clear than that of Shu,[3] but Egyptologists have suggested she is connected with moisture, based on a passage in the Pyramid Texts in which she produces water, and on parallelism with Shu's connection with dry air.[4][5] She was also one of the goddesses who could function as the fiery Eye of Ra.[6]

| Tefnut | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

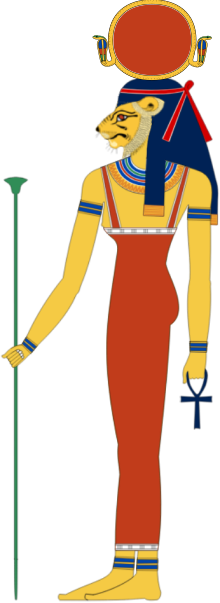

The goddess Tefnut portrayed as a woman with the head of a lioness and a sun disc resting on her head. | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Heliopolis, Leontopolis | ||||

| Symbol | Lioness, Sun Disk | ||||

| Genealogy | |||||

| Parents | Ra or Atum | ||||

| Siblings | Shu, Hathor, Maat, Anhur, Sekhmet, Bastet, Mafdet, Satet | ||||

| Consort | Shu, Geb | ||||

| Offspring | Geb and Nut | ||||

Etymology

editThe name Tefnut has no certain etymology but it may be an onomatopoeia of the sound of spitting, as Atum spits her out in some versions of the creation myth. Additionally, her name was written as a mouth spitting in late texts.[7]

Like most Egyptian deities, including her brother, Tefnut has no single ideograph or symbol. Her name in hieroglyphs consists of four single phonogram signs t-f-n-t. Although the n phonogram is a representation of waves on the surface of water, it was never used as an ideogram or determinative for the word water (mw), or for anything associated with water.[8]

Mythological origins

editTefnut is a daughter of the solar deity Ra-Atum. Married to her twin brother Shu, she is mother of Nut, the sky and Geb, the earth. Tefnut's grandchildren were Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and, in some versions, Horus the Elder. She was also the great-grandmother of Horus the Younger. Alongside her father, brother, children, grandchildren, and great-grandchild, she is a member of the Ennead of Heliopolis.

There are a number of variants to the myth of the creation of the twins Tefnut and Shu. In every version, Tefnut is the product of parthenogenesis, and all involve some variety of body fluid.

In the Heliopolitan creation myth, Atum sneezed to produce Tefnut and Shu.[9] Pyramid Text 527 says, "Atum was creative in that he proceeded to sneeze while in Heliopolis. And brother and sister were born - that is Shu and Tefnut."[10]

In some versions of this myth, Atum also spits out his saliva, which forms the act of procreation. This version contains a play on words, the tef sound which forms the first syllable of the name Tefnut also constitutes a word meaning "to spit" or "to expectorate".[10]

The Coffin Texts contain references to Shu being sneezed out by Atum from his nose, and Tefnut being spat out like saliva. The Bremner-Rind Papyrus and the Memphite Theology describe Atum as sneezing out saliva to form the twins.[11]

Iconography

editTefnut is a leonine deity, and appears as human with a lioness head when depicted as part of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis. The other frequent depiction is as a lioness, but Tefnut can also be depicted as fully human. In her fully or semi anthropomorphic form, she is depicted wearing a wig, topped either with a uraeus serpent, or a uraeus and solar disk, and she is sometimes depicted as a lion headed serpent. Her face is sometimes used in a double headed form with that of her brother Shu on collar counterpoises.[12]

During the 18th and 19th Dynasties, particularly during the Amarna Period, Tefnut was depicted in human form wearing a low flat headdress, topped with sprouting plants. Akhenaten's mother, Tiye was depicted wearing a similar headdress, and identifying with Hathor-Tefnut. The iconic blue crown of Nefertiti is thought by archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley to be derived from Tiye's headdress, and may indicate that she was also identifying with Tefnut.[13]

Cult centres

editHeliopolis and Leontopolis (now ell el-Muqdam) were the primary cult centres. At Heliopolis, Tefnut was one of the members of that city's great Ennead,[12] and is referred to in relation to the purification of the wabet (priest) as part of the temple rite. Here she had a sanctuary called the Lower Menset.[4]

I have ascended to you

with the Great One behind me

and [my] purity before me:

I have passed by Tefnut,

even while Tefnut was purifying me,

and indeed I am a priest, the son of a priest in this temple."

— Papyrus Berlin 3055[14]

At Karnak, Tefnut formed part of the Ennead and was invoked in prayers for the health and wellbeing of the pharaoh.[15]

She was worshiped with Shu as a pair of lions in Leontopolis in the Nile Delta.[4]

Mythology

editTefnut was connected with other leonine goddesses as the Eye of Ra.[16] As a lioness she could display a wrathful aspect and is said to have escaped to Nubia in a rage, jealous of her grandchildren's higher worship. Only after receiving the title "honorable" from Thoth, did she return.[7] In the earlier Pyramid Texts she is said to produce pure waters from her vagina.[17]

As Shu had forcibly separated his son Geb from his sister-wife Nut, Geb challenged his father Shu, causing the latter to withdraw from the world. Geb, who was in love with his mother Tefnut, takes her as his chief queen-consort.[18]

References

edit- ^ "Tfn.t (Lemma ID 171880)". Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae.

- ^ Love, Edward O. D. (2021). "Innovative Scripts and Spellings at Narmoute/Narmouthis". Script Switching in Roman Egypt. de Gruyter. p. 312. doi:10.1515/9783110768435-014. ISBN 9783110768435. S2CID 245076169.

- ^ Allen, James P. (1988). Genesis in Egypt: The Philosophy of Ancient Egyptian Creation Accounts. Yale Egyptological Seminar. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-912532-14-1.

- ^ a b c Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Second Edition. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-203-02362-4.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 183. ISBN 0-500-05120-8. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Betro, Maria Carmela (1996). Hieroglyphics: The Writings of Ancient Egypt. Abbeville Press. pp. 163. ISBN 0-7892-0232-8.

- ^ Hassan, Fekri A (1998). "5". In Goodison, Lucy; Morris, Christine (eds.). Ancient Goddesses. London: British Museum Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-7141-1761-7.

- ^ a b Watterson, Barbara (2003). Gods of Ancient Egypt. Sutton Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 0-7509-3262-7.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-57607-242-4.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Richard H (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 183. ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- ^ Tyldesley, Joyce (2005). Nefertiti: Egypt's Sun Queen (2nd ed.). Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0140258202. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Hays, H.M (2009). Nyord R, Kyolby A (ed.). "Between Identity and Agency in Ancient Egyptian Ritual". Leiden University Repository: Archaeopress: 15–30. hdl:1887/15716.

Rite 25 from Moret, Le Rituel de Cult, Paris 1902

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Meeks, Dimitri; Christine Favard-Meeks (1999). Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods. Pimlico. p. 128. ISBN 0-7126-6515-3.

- ^ Watterson, Barbara (2003). Gods of Ancient Egypt. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3262-7.

- ^ The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, trans R.O. Faulkner, line 2065 Utt. 685.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 76. ISBN 1576072428.

External links

edit- Media related to Tefnut at Wikimedia Commons