Tallaght (/ˈtælə/ TAL-ə; Irish: Tamhlacht, IPA: [ˈt̪ˠəul̪ˠəxt̪ˠ]) is the largest settlement, and county town, of South Dublin, Ireland, and the largest satellite town of Dublin. The central village area was the site of a monastic settlement from at least the 8th century, which became one of medieval Ireland's more important monastic centres.[2]

Tallaght

Tamhlacht | |

|---|---|

Suburban town | |

From top, left to right: Skyline from Sean Walsh Park, High Street, Luas terminus; The Square Tallaght | |

| Motto(s): Aontacht (Irish: Unity) | |

| Coordinates: 53°17′19″N 6°21′26″W / 53.2886°N 6.3572°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Leinster |

| County | South Dublin |

| Traditional county | County Dublin |

| Government | |

| • Dáil constituency | Dublin South-West |

| Elevation | 90 m (300 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 81,022[1] |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing key | D24 |

| Telephone area code | +353 (0)1 |

| Irish Grid Reference | O093265 |

Up to the 1960s, Tallaght was a small village in the old County Dublin, linked to several nearby rural areas which were part of the large civil parish of the same name—the local council estimates the population then to be 2,500.[3] Suburban development began in the 1970s and a "town centre" area has been developing since the late 1980s. There is no legal definition of the boundaries of Tallaght, but the 13 electoral divisions known as "Tallaght" followed by the name of a locality have, according to the 2022 census, a population of 81,022,[1] up from 76,119 over six years.[4] This makes Tallaght the largest settlement on the island without city status, however there have been calls in recent years for it to be declared one.[5]

The village core of the district is located north of, and near to, the River Dodder, and parts of the broader area within South Dublin are close to the borders of Dublin City, County Kildare, Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown and County Wicklow. Several streams flow in the area, notably the Jobstown or Tallaght Stream (a tributary of the Dodder), and the Fettercairn Stream (a tributary of the River Camac), while the Tymon River, the main component of the River Poddle (Liffey tributary), rises in Cookstown, near Fettercairn.

Tallaght is also the name of an extensive civil parish, which includes other areas of southern and southwestern Dublin, from Templeogue to Ballinascorney in the mountains. A book about the civil parish was published in the 19th century, The History and Antiquities of Tallaght in the County of Dublin, written by William Domville Handcock.[2]

Etymology

editThe place-name Tallaght is said to derive from támh-leacht, meaning "plague pit" in Irish, and consisting of "támh", meaning plague, and "leacht", meaning grave or memorial stone. The earliest mention of a Tallaght is in Lebor Gabála Érenn ("The Book Of Invasions"), and is there linked to Parthalón, said to be the leader of an early invasion of Ireland. He and many of his followers were said to have died of the plague. The burials that have been found in the Tallaght area, however, are all normal pre-historic interments, mainly from the Bronze Age, and nothing suggesting a mass grave has so far been recorded here. The Annals of the Four Masters record the legendary event as follows:

- Naoi mile do ecc fri h-aoin-sechtmain do muinter Parthaloin for Shenmhaigh Ealta Eadoir .i. cúig míle d'feroibh, & ceithre míle do mnáibh. Conadh de sin ata Taimhleacht Muintere Parthalain. Trí ced bliadhain ro caithsiot i n-Erinn."[6]

In translation:

- "Nine thousand of Parthalón's people died in one week on Sean Mhagh Ealta Edair, namely, five thousand men, and four thousand women. Whence is named Taimhleacht Muintire Parthalóin. They had passed three hundred years in Ireland."[7]

The name in Irish, Tamhlacht, is found at other places, such as Tamlaght in Magherafelt District, Northern Ireland, though the mention of Eadoir, probably Binn Éadair (Howth) in the passage below, suggests that Tallaght is the more likely location for this tale.

Places near Tallaght featured in the ancient legends of the Fianna, a band of warriors that roamed the country and fought for the High King at Tara. In Lady Gregory's Gods and Fighting Men, mention is made of, in particular, Gleann na Smól: in Chapter 12 "The Red Woman", on a misty morning, Fionn says to his Fians, "Make yourselves ready, and we will go hunting to Gleann-na-Smol".[8] There they meet Niamh of the Golden Hair, who chose Oisín from among all the Fianna to be her husband, told him to come with her on her fairy horse, after which they rode over the land to the sea and across the waves to the land of Tír na nÓg.

History

edit8th to 12th centuries

editWith the foundation of the monastery of Tallaght by St. Maelruain in 769 AD, there is a more reliable record of the area's early history.[citation needed] The monastery was a centre of learning and piety, particularly associated with the Céli Dé spiritual reform movement. It was such an important institution that it and the monastery at Finglas were known as the "two eyes of Ireland".[9] St. Aengus, an Ulsterman, was one of the most illustrious of the Céli Dé and devoted himself to the religious life. Wherever he went, he was accompanied by a band of followers who distracted him from his devotions. He secretly travelled to the monastery at Tallaght where he was not known and enrolled as a lay brother. He remained unknown for many years until his identity was discovered by Maeilruain. They may have written the Martyrology of Tallaght together, and St Aengus also wrote a calendar of saints known as the Félire Óengusso ("Martyrology of Aengus"). St. Maelruain died on 7 July 792 and was buried in Tallaght. The influence of the monastery continued after his death, as can be judged by the fact that, in 806, the monks of Tallaght were able to prevent the holding of the Tailteann Games, because of some infringement of their rights. [citation needed]

In 811 A.D., the monastery was devastated by the Vikings but the destruction was not permanent and the annals of the monastery continued to be recorded for several following centuries. After the Anglo-Norman invasion in 1179, Tallaght and its appurtenances were confirmed to the Diocese of Dublin and became the property of the Archbishop. The complete disappearance of every trace of what must have been an extensive and well-organised monastic settlement can only be accounted for by the subsequent history of the place, the erection and demolition of defensive walls and castles, and the incessant warfare and destruction that lasted for hundreds of years.[citation needed]

13th to 20th centuries

editThroughout the greater part of the 13th century a state of comparative peace existed at Tallaght, but subsequently, the O'Byrnes and O'Tooles, in what would become County Wicklow, took offensive action and were joined by many of the Archbishop's tenants. As a result of this the land was not tilled, the pastures were not stocked and the holdings were deserted. In 1310 the bailiffs of Tallaght got a royal grant to enclose the town. No trace of these defensive walls survive and there is no evidence of their exact location, except, perhaps, for the name of the Watergate Bridge which spans the Dodder on the Oldbawn Road.[citation needed] The continuation of such raids prompted the construction, in 1324, of Tallaght Castle, and it was finished sometime before 1349. Tallaght had become an important defensive site on the edge of the Pale. A century later the castle was reported to be in need of repair.[citation needed]

The 17th and 18th centuries brought many changes to Tallaght. Many mills were built along the Dodder and this brought new prosperity to the broad area, which saw the building of many houses.[citation needed]

When Archbishop Hoadley replaced Archbishop King in 1729 he found the castle in ruins and had it demolished, building himself a palace at a cost of £2,500. By 1821 the palace too had fallen into ruin and an Act of Parliament was passed which stated that it was unfit for habitation. The following year it was sold to Major Palmer, Inspector General of Prisons, who pulled the palace down and used the materials to build his mansion, Tallaght House, as well as a schoolhouse and several cottages. Parts of Tallaght House, including one tower, were incorporated into St Joseph's Retreat House, situated on the grounds of St Mary's Priory; the rest was demolished. That tower contains a spiral staircase and was originally four storeys high but is now reduced internally to two. Attached to the castle was a long building that was used in the archbishop's time as a brewery and later as a granary and stables. When the Dominicans came, it was converted into a chapel and was used as such until 1883, when the new church dedicated to Fr Tom Burke (now the older part of the parish church) was built.[citation needed]

The Dominicans came to Tallaght in 1855/6 and soon established a priory that was also a seminary for the formation of Dominicans in Ireland and on missions in Trinidad and Tobago, South America, Australia, India, and elsewhere. The cramped accommodation of Tallaght house was replaced by the austere priory in phases of 1864, 1903 and again in 1957. The work that goes on in these buildings is various: St Joseph's retreat house, the Tallaght parish, St Catherine's counselling centre, at least two publishing enterprises, individual writing and international research in several domains.[citation needed]

The grounds of the Priory, the old palace gardens, still retain older features such as the Archbishop's bathhouse, the Friar's Walk and St. Maelruain's Tree, a Persian walnut of the eighteenth century.[citation needed]

The old constabulary barracks on the main street were the scene of the engagement known as the 'Battle of Tallaght', which occurred during the Fenian Rising on 5 March 1867. On that night the Fenians moved out to assemble at the appointed place on Tallaght Hill. The large number of armed men alarmed the police in Tallaght who sent a warning to the nearest barracks. There were fourteen constables and a head constable under Sub-inspector Burke at Tallaght, and they took up a position outside the barracks where they commanded the roads from both Greenhills and Templeogue. The first body of armed men came from Greenhills and, when they came under police fire, retreated. Next, a party came from Templeogue and was also dispersed.[citation needed] In 1936 a skeleton, sword-bayonet and water bottle were found in a hollow tree stump near Terenure. It is thought that these were the remains of one of the Fenians who had taken refuge there after the Battle of Tallaght and either died of his wounds or was frozen to death.[citation needed]

In 1888 the Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway opened and it passed through Tallaght Village. This provided a new means of transporting goods and also brought day-trippers from the city.

Modern development

editWhile no plan was formally adopted, Tallaght was laid out as a new town, as set out in the 1967 Myles Wright masterplan for Greater Dublin (this proposed four self-contained "new towns" - at Tallaght, Clondalkin, Lucan and Blanchardstown - around Dublin, all of which were, at that time, villages surrounded by extensive open lands, with some small settlements). Many of the social and cultural proposals in this plan were ignored by the Dublin local authorities, and contrary to planners' suggestions, Tallaght and the other "new towns" were not provided with adequate facilities. Characterised by the same problems associated with poorly planned fringe areas of many European cities, during the 1970s and 1980s Tallaght became synonymous with suburban mismanagement.

While it was absorbed into the larger suburban area of Dublin (including being included in the postal district Dublin 24 in the 1980s), Tallaght has developed a distinctive identity, arising largely from its rapid growth during recent decades, and now has active local arts, cultural, sports, and economic scene.

Tallaght's Civic Square contains the seat of the local authority, County Hall, a modern and well-equipped library facility, a theatre building and a "cutting edge" 4-storey arts centre named "Rua Red" (which opened on 5 February 2009). This facility offers activities in the areas of music, dancing, art, drama and literature.[10] Along with other local libraries and arts groups, it also has another theatre building and a homegrown youth theatre company. It is also the home to the Tallaght Swim Team, Tallaght Rugby Club, the National Basketball Arena, Shamrock Rovers F.C., and several martial arts schools and Gaelic Athletic Association clubs.

Chronology

edit- 769: Saint Maelruain's monastery founded.

- 792: AI792.1 Kl. Mael Rúain, bishop of Tamlachta, [rested].

- 811: Saint Maelruain's monastery was devastated by the Vikings.

- 824: "Tamlachta of Mael Ruain plundered by the community of Cell Dara.

- 1179: Tallaght and its hinterland, previously within the Diocese of Glendalough, were confirmed as holdings of the Archdiocese of Dublin.[11]

- 1310: bailiffs of Tallaght given royal grant to enclose the town.

- 1324: Alexander de Bicknor begins the building of Tallaght Castle.

- 1331-1332; Tallaght Castle plundered by O'Toole of Imaile.

- 1378: Mathew, son of Redmond de Bermingham, takes up station at Tallaght Castle to resist the O'Byrnes.

- 1540: O'Tooles invade, and devastate Tallaght Castle and surrounding manors.

- 1635: Old Bawn House was built.

- 1729: Tallaght Castle demolished; Archbishop's Palace built by Archbishop Hoadley.

- 1822: Archbishop's Palace was demolished by Major Palmer, who then builds Tallaght House.

- 1829: Modern Church of Ireland parish created.

- 1856: Tallaght House is sold to the Dominicans.

- 1864: Saint Mary's Priory was built.

- 1867: Battle of Tallaght fought in March.[12] 2 July 1882, Tom Bourke O.P. dies.

- 1883: New Priory Church built.

- 1888: The Dublin and Blessington Steam Tramway commences operation, passing through Tallaght village.

- 1903: New wing was built at the Priory, connecting Priory and the church

- 1955: New retreat house built at the Priory, enclosing Tallaght House.

- 1955: Michael Cardinal Browne buried in Tallaght Dominican church

- 1984: Public library, at Castletymon, opened in June.

- 1987: Alan Dukes outlines the Tallaght Strategy to the Tallaght Chamber of Commerce.

- 1990: The Square shopping centre opens.

- 1992: Institute of Technology, Tallaght opens.

- 1994: South Dublin County Council comes into existence, with new headquarters at Tallaght; Tallaght Youth Theatre is founded; Tallaght's second public library, situated beside the South Dublin County Council offices, opened in December.

- 1997: Tallaght Theatre is officially opened, on Greenhill's Road in Kilnamanagh.

- 1998: Tallaght Hospital opens.

- 1999: Civic Theatre opens adjacent to County Council headquarters in Tallaght centre.

- 2004: The Red Line of the Luas light rail system opens, connecting central Tallaght to Heuston Station and Connolly Station in Dublin City.

- 2008: Extensive rebuilding of Tallaght's main library is completed; the first attempt to design a flag specifically for Tallaght results in An Bratach Fulaingt (The Suffering Flag), created as part of a Tallaght Youth Theatre project on citizenship.

- 2009: The County Arts Centre, Rua Red, is opened; completion of Tallaght Stadium; An Bratach Fulaingt is utilised in a performance by Tallaght Youth Theatre at the Rua Red Arts Centre.

- 2011: On 15 September Shamrock Rovers hosted Rubin Kazan in what was the first UEFA Europa League group stage game to contain an Irish team. This game took place in the Tallaght Stadium which would host 2 more games in the group stage.[13]

- 2017: An Bhratach Aontacht Thamlachta (The Unity Flag of Tallaght) is adopted by Tallaght Historical Society and Tallaght Community Council as an unofficial flag for the entire Tallaght area and is flown publicly from a flag pole at the Priory in Tallaght village during Tallafest on 24 June.[citation needed]

Geography

editLocation

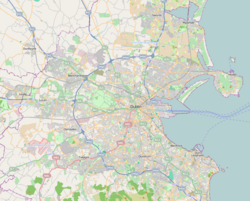

editTallaght is centred 13 km southwest of Dublin city, near the foothills of the Wicklow Mountains. While there is no formal definition as such, it can be described as beginning southwest of Templeogue, running west towards Saggart, southwest towards the mountain areas of Bohernabreena, Glenasmole and Brittas, southeast towards Firhouse, and to the southern edges of Clondalkin in the northwest and Greenhills in the northeast. It lies outside the M50 Dublin orbital motorway, and in effect forms an irregular circle on either side of the N81 Dublin-Blessington road. The suburban villages of Saggart and Rathcoole, and the Citywest campus, with growing amounts of housing, lie west of Tallaght, along with the Air Corps aerodrome at Baldonnel. There is also still considerable open land, some still actively farmed, in this direction.

The village core of the district is located north of, and near to, the River Dodder, and several streams flow in the area. The Jobstown Stream[14] or Tallaght Stream[15] (a tributary of the Dodder), approaches from the west, and takes in at least one tributary, the Killinarden Stream from the south, near the N81.[14] The Fettercairn Stream (a tributary of the River Camac), also passes through the northwest fringes of the area, while the Tymon River, the main component of the River Poddle (an historically important Liffey tributary), rises in Cookstown, near Fettercairn.

Transport

editTallaght is connected to Dublin city by bus services and by the Red Line of the Luas light rail system, which opened in September 2004. Though the first stop (Tallaght Cross) of the Red Line is called Tallaght, most of the 'Red 4' zone (with the exception of the stops at Citywest Campus, Fortunestown and the terminus at Saggart) lies within the broader Tallaght area. The other stops that serve Tallaght include Belgard (which is the last stop before the junction), Fettercairn, Cheeverstown, Cookstown and Hospital. As of 2013, a single ticket from Red 4 to Central 1 was €2.70.[citation needed]

Tallaght is not well connected to Dublin's other towns and suburbs,[original research?] as public transport lines predominantly run through the city centre; this has led to high levels of car dependence. However the 76 bus route links Tallaght to Clondalkin, Liffey Valley Shopping Centre and Ballyfermot, while the S8 connects to Citywest, Rathfarnham, Ballinteer, Dundrum, Sandyford, Leopardstown, Stillorgan, Monkstown and Dún Laoghaire, and the S6 connects with Templeogue, Dundrum and UCD and Blackrock. According to a 2019 consultation paper for the BusConnects project, Tallaght would be establish as a public transport hub for surrounding villages and suburbs.[16]

Routes to the city centre include the 27 (via Jobstown and Tymon Park), 49 (The Square, Aylesbury, Oldbawn, Ballycullen and Firhouse), 54a (Kiltipper, Killinarden Heights, The Square, Tallaght Hospital, Tallaght Village, Balrothery), 56a (The Square, Springfield, Fettercairn and Kingswood), 65 (The Square, Tallaght Hospital, Tallaght Village and Balrothery), 65b (Killinarden Heights, Kiltipper Road, Aylesbury, Old Bawn, Firhouse and Ballycullen) and 77a (Blessington, Killinarden Heights, The Square, Tallaght Hospital, Tallaght Village, Oldbawn, Balrothery and Tymon Park).

Former routes include the 75 (The Square, Rathfarnham, Ballinteer, Dundrum, Stillorgan, and Dún Laoghaire) and 175 (Citywest, Dundrum and UCD). Since 26 November 2023, they have been withdrawn and largely replaced with the brand new S6 and S8 routes.

A metro rail line, Metro West, was proposed to pass through Tallaght but was shelved in 2011.[17] Early plans for the line proposed to link Tallaght with several satellite towns west of Dublin city, including Clondalkin, Lucan, and Blanchardstown. If completed as proposed it would also join with Metrolink and continue out to Dublin Airport. The first 4 stops of the proposed Metro West were to be in Tallaght, with the first stop, 'Tallaght East' being situated near Tallaght IT, now the Tallaght Campus of Technological University Dublin.[citation needed]

A Luas extension from Belgard to Saggart and Citywest was added to the original Luas system. This is a 4.2 km (2.5 mi) extension, funded by a Public-Private Partnership with property developers, including Davy Hickey Properties. Identified as Line A1, this €150 million spur off the Red Line at Belgard runs to Saggart. Originally intended to be a spur of the proposed Red Line as far as Fortunestown, it was later decided to extend it to Saggart. Construction started on 9 February 2009, with the line completed by early 2011. Passenger services on the 4.2 km light rail link started in early 2011. It serves housing developments such as Cairnwood, Ambervale, Belgard Green, Fettercairn, Kilmartin, Brookview, Ardmore, Citywest and Russell Square.

Population

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1653 | 145 | — |

| 1659 | 391 | +169.7% |

| 1821 | 510 | +30.4% |

| 1831 | 359 | −29.6% |

| 1841 | 348 | −3.1% |

| 1851 | 375 | +7.8% |

| 1861 | 537 | +43.2% |

| 1871 | 312 | −41.9% |

| 1881 | 267 | −14.4% |

| 1891 | 289 | +8.2% |

| 1901 | 299 | +3.5% |

| 1911 | 232 | −22.4% |

| 1926 | 333 | +43.5% |

| 1936 | 406 | +21.9% |

| 1946 | 378 | −6.9% |

| 1951 | 352 | −6.9% |

| 1956 | 710 | +101.7% |

| 1961 | 1,402 | +97.5% |

| 1966 | 2,476 | +76.6% |

| 1971 | 6,174 | +149.4% |

| 1981 | 55,104 | +792.5% |

| 1986 | 46,833 | −15.0% |

| 1991 | 62,570 | +33.6% |

| 1996 | 61,611 | −1.5% |

| 2002 | 60,215 | −2.3% |

| 2006 | 65,167 | +8.2% |

| 2011 | 69,454 | +6.6% |

| 2016 | 76,119 | +9.6% |

| 2022 | 81,022 | +6.4% |

| [18][1] | ||

South Dublin County Council stated in 2003 that the population of Tallaght and environs was just under 73,000.[3] Tallaght is the seat of South Dublin County Council and has no specific local administration. In addition, while there exist two distinct local electoral areas in the form of "Tallaght Central" (based around the historic village core and key modern developments) and "Tallaght South" (the outlying "suburbs" and some rural areas), Tallaght possesses no legal boundary and as a result, it is very difficult to define an official population figure for the area. The population of the village remains modest but the broader area is now one of Ireland's largest population agglomerations. If the entirety of Tallaght and its broadly defined environs were taken into account, then the population would be greater than that of Galway City (75,414), rendering Tallaght the fourth largest area by population in the state. Irish population statistics are calculated from District Electoral Divisions, and these are often combined to estimate "area populations". As of the 2016 census, the total population of the area was 76,119.

| Tallaght Ethnic groups 2011 | White Irish | Irish Traveller | Other White | Black | Asian | Other | Not Stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tallaght Population 69,454 | 58,596 | 787 | 3,934 | 2,001 | 1,271 | 856 | 2,009 |

The population of the historic civil parish of Tallaght, including areas such as Templeogue, Ballyroan, and wide areas of mountain as far away as Castlekelly, is 101,059.[20]

Districts

edit"Greater Tallaght" comprises Tallaght village and a range of areas that were formerly small settlements (Jobstown, Old Bawn, Kilnamanagh) and rural townlands.[citation needed]

The original village of Tallaght lies west of the Tallaght Bypass (N81). It stretches east–west from Main Road and Main Street to the Abberley Court Hotel at the end of High Street and encompasses the Village Green shopping plaza, Tallaght Courthouse, Westpark, and many shops, and restaurants and banks. It also houses Tallaght Youth Service, Tallaght's first newspaper printing house the Tallaght Echo, and (formally) Tallaght Community Arts Centre. The area's Institute of Technology, Saint Mary's Priory, and Saint Maelruain's Church are located in the historic quarter of Tallaght village.

The newer "town centre" lies immediately to the south across the Belgard Road, encompassing Belgard Square, the main shopping complex (known as The Square also known as the Pyramid), the Luas Red Line terminus, Tallaght Hospital (including the National Children's Hospital), County Hall, the Civic Theatre, South Dublin County Library, Rua Red Arts Centre, and several bars, restaurants and hotels.

To the northeast of the village lies the Tymon North / Balrothery area, which comprised rural townlands until the 1970s.[citation needed] This district includes estates such as Bancroft, Balrothery, Glenview, Castle Park, Saint Aongus, Tymon, Bolbrook and Avonbeg. These areas are home to several sporting facilities, including the National Basketball Arena, a fitness centre, two swimming pools, an athletics track, and an astroturf football facility. Tymon Park is watered by the River Poddle and borders Greenhills and Templeogue. It contains sporting grounds, ponds, Coláiste De Hide and a large playground at the Tymon North entrance.[citation needed]

Old Bawn, formerly a small village in its own right, is immediately south of the village, bordered by Sean Walsh Memorial Park (also locally called Watergate). To the east of Old Bawn, estates include Home Lawns, Mountain Park, Millbrook Lawns and Seskin View. To the south and southwest of the village lie Ellenborough, Aylesbury, and Killinarden (the latter comprising the residential areas of Deer Park, Cushlawn, Donomore, Killinarden Estate and Knockmore). Beyond these are rural lands, running towards the Wicklow Mountains.

In the northwest is Belgard Green, with Belgard Heights (built 1974) to the north.[citation needed] Half of Kingswood is served by Clondalkin Garda Station. Kingswood and Belgard Heights are adjacent to Clondalkin, while Kilnamanagh is situated beside Greenhills and south-west of Walkinstown and Crumlin. Tallaght Theatre is situated along Greenhills Road.

Virginia Heights and Springfield are close to the area's centre, and further west of the town centre is the former hamlet of Jobstown, which is divided from Central Tallaght via the N81 and the Cheeverstown Road, Jobstown now has dense housing estates, and also the previously rural areas of Kiltalown, Brookfield and Fettercairn. [citation needed]

Features

editHistorical features in the area include St. Maelruain's Church and Tallaght Castle

The more modern "town centre" area of Tallaght holds offices of local and central government entities, including South Dublin County Council, the Revenue Commissioners, the Department of Social and Family Affairs, the Health Service Executive (Eastern Region), County Dublin V.E.C., as well as local FÁS offices. It is also the location of the County Library, Rua Red - the County Arts Centre, the Civic Theatre, and many shops, bars, and restaurants. Tallaght University Hospital is located nearby.

Tallaght is home to The Square (stylised as "sq."), one of Ireland's largest shopping centres, with three retail levels and accessible by the Luas and by bus. Anchor tenants at the centre include Tesco, Easons, Heatons and Dunnes Stores. Tallaght's 12-screen United Cinemas International cinema closed in March 2010, but was replaced in April 2012 when a 13-screen IMC cinema opened in place of the old one.[citation needed]

Five hotels are located in the "town centre" area: the Plaza Hotel near The Square, the Abberley Court Hotel at High Street, the Maldron Hotel at Whitestown Way, near Seán Walsh Park, and the Glashaus Hotel and Tallaght Cross Hotel at "Tallaght Cross", near the Tallaght Luas Stop.

Across the N81 dual carriageway - south of the "town centre" - is the 10,000-seat football ground called Tallaght Stadium. Initially, construction was undertaken by Shamrock Rovers F.C. on lands belonging to South Dublin County Council, but the project was marred by financial problems, and the site reverted to council ownership. Work on the site recommenced on 6 May 2008,[21] after a judicial review taken by a local GAA club had been thrown out of court the preceding January.[22]

Sean Walsh Memorial Park also lies south of the N81.[citation needed]

Politics and government

editTallaght is represented, within the Dublin South-West constituency in Dáil Éireann, with four TDs.[23] It is divided into two electoral areas for South Dublin County Council elections - Tallaght Central and Tallaght South - and between these 12 councillors are elected.[citation needed]

Education

editSchools in Tallaght include St. Mark's National School, St. Mark's Community School, Scoil Maelruain, St. Martin de Porres, St. Dominic's NS, St. Aidan's, St. Thomas', Holy Rosary NS, Scoil Treasa, Old Bawn Community School, Tallaght Community School, Killinarden Community School, Coláiste de hÍde gaelscoil,[24] St. Aidan's Community School, Firhouse Community College and Mount Seskin Community School.[25]

Tallaght is home to one of the campuses of the Technological University Dublin, formerly Institute of Technology, Tallaght (ITT), a third-level college offering undergraduate degrees[26] as well as higher certificates and post-graduate professional qualifications, founded in 1992 as the Regional Technical College, Tallaght. The Priory Institute at the Dominican, St. Mary's Priory, runs certificate, diploma and degree courses in Theology and Philosophy.

Sports

editAssociation football

editShamrock Rovers F.C. is based in Tallaght, and started playing in Tallaght Stadium in 2009. The club finished its first season in Tallaght as runners-up in the league. The club won their 16th League title in 2010.[27][28] Rovers followed this up by winning the 2011 League of Ireland. Rovers hosted their first game in European competition in Tallaght in the second qualifying round of the 2010–11 UEFA Europa League against Bnei Yehuda from Israel, with Rovers advancing 2–1 on aggregate. Rovers faced former Champions League and UEFA Cup winners Juventus, Rovers were beaten 2–0 in Tallaght and 3–0 on aggregate. In 2011 the club played its first-ever Champions League game and its first game in the highest level of European Cup Competition since the 1987–88 European Cup, beating Estonian Champions Flora Tallinn in the 2011–12 Champions League Second qualifying round. Rovers were then beaten 3–0 on aggregate in the next round by Danish Champions F.C. Copenhagen but advanced to the 2011-12 Europa League Play-off round. There they were drawn against Serbian Champions FK Partizan, whom they defeated 3–2 on aggregate (2-1 on the night after extra time) to reach the group stages of the Europa League. Rovers also won the All Ireland Setanta Sports Cup in 2011. Rovers wrapped up a second league title in a row on 25 October 2011.[29][30]

St Maelruans FC is located in Bancroft Park near Tallaght Village. They were founded in 1968, and have teams playing at underage levels and a senior team playing football in the Leinster Senior League.[31] Newtown Rangers AFC is located at Farrell Park, Kiltipper. They were founded in 1957 and have two senior teams playing in the Leinster Senior League.

Brookfield Celtic, one of Dublin's largest underage football clubs, was founded in Tallaght in 1999. Kingswood Castle FC is another local men's soccer club. Founded in 2013, they play their home matches in Ballymount park. The club's home colours are black and white.

Gaelic games

editSaint Anne's GAA, Saint Marks GAA and Thomas Davis GAA Club are local Gaelic Athletic Association clubs.

Sports amenities and events

editThe National Basketball Arena lies east of the village.

The trailhead of the Dublin Mountains Way, a long-distance walking route across the Dublin side of the Wicklow Mountains between Tallaght and Shankill, begins at Sean Walsh Park near Tallaght Stadium.[32]

In July 1998, a section of the Tour de France routed through Tallaght.[33]

Other sports

editTallaght Swim Team is located at the Tallaght Sports Complex, Balrothery, beside Tallaght Community School.[34]

Glenanne Hockey Club is based in Tallaght, playing their home games on the astroturf pitch located in St. Marks Community School.

South Dublin Taekwondo and Eire Taekwondo Association are the only WTF (Olympic Style) Taekwondo clubs in Tallaght. Eire Taekwondo Association was founded in 1988 as St. Martin's Taekwondo club and has since been rebranded and grown to include clubs around Dublin County, as well as in other counties. South Dublin Taekwondo was founded in 2008 and are tenants in the Tallaght Leisure Centre. There are several I.T.F style Taekwon-do clubs in the area.[citation needed]

Tallaght Rugby Football Club was founded as a youth team in 2002 with financial support from the IRFU before setting up a senior team in 2006.[citation needed]

Arts and entertainment

editTallaght Theatre, Tallaght's first dedicated theatre, was launched in 1975 by a not-for-profit amateur dramatic group. It is situated on Greenhills Road.[35] Built sometime later in 1999 beside the civic offices, the Civic Theatre became Tallaght's second theatre.[36]

Rua Red hosts arts/entertainment events and groups.[37] Tallaght Young Filmmakers are a youth filmmaking group initiated by South Dublin County Council's Arts Office in partnership with local young people.[38]

Movies@ The Square is a cinema located in the Square shopping centre. The cinema boasts 11 screens and a V.I.P lounge. The site previously housed UCI Cinemas, before being closed and re-opened as IMC Cinemas. IMC closed down this location during the Covid-19 pandemic, with the Movies@ The Square re-opening in 2021.

Irish language use

editTallaght has a vibrant and intergenerational network of urban Irish speakers. This is supported by Gaelphobal Thamhlachta, a cultural association which grew out of Cumann Gaelach Thamhlachta, founded in 1974 as a branch of the Gaelic League.[39]

Particular emphasis has been placed on providing education through Irish. There are now three Gaelscoileanna (Irish-speaking primary schools), Scoil Santain (founded in 1979),[40] Scoil Chaitlín Maude (founded in 1986)[41] (Caitlín Maude, after whom the latter is named, was a well-known Irish-language poet, singer and activist who settled in the area), as well as Scoil na Giúise founded in 2012. There is also an Irish-medium secondary school, Coláiste de hÍde.[42]

The importance of the language was given official recognition in 2015 with the announcement of a €50,000 council grant to Gaelphobal Thamhlachta, supplemented by a government grant of €150,000 in 2016, meant to facilitate the creation of a local Irish-language cultural centre, including a public cafe staffed by local Irish speakers.[43][44] A further €30,000 was granted by South Dublin County Council in 2019 to help develop a theatre as part of a cultural centre at 518 Tallaght Village. Gaelphobal Thamhlachta opened a bilingual café named 'Aon Scéal?' as part of a cultural centre in Tallaght village in December 2019.[citation needed]

Flag projects

editIn October 2008 An Bhratach Fhulaingt[45] or The Suffering Flag was designed for Tallaght during The D'No Project[further explanation needed], run by Tallaght Youth Theatre in partnership with Tallaght Community Arts, and funded by Léargas - and was intended to be flown at the new county arts centre, Rua Red, on 17 and 18 April 2009. However, the flag was ultimately not flown and instead, its colours were utilised within aspects of the performance.[46]

The flag developed into "An Bhratach Seasmhacht",[47] or "The Endurance Flag", which was flown from The Cabin at the Fettercairn Community Centre for 12 months, as part of Tallaght Community Arts 'Headin' Out Project' between 2013 and 2014.

The Tallaght Unity Flag

editDesigned by Seos Ó Colla and launched in August 2017 after a decade of development by the Tallaght Historical Society, An Bratach Aontacht Thamlachta[48] or The Tallaght Unity Flag has been adopted as a flag for Tallaght by both the Tallaght Historical Society and the Tallaght Community Council. The flag was first flown publicly from a flagpole at the Priory in Tallaght village during Tallafest 2017. Since Easter 2018, it has also been displayed at the Dragon Inn,[49][50] and as of August 2018, it is also flown at Molloy's The Foxes Covert, a pub in Tallaght village.[51][52]

In September 2017, The Tallaght Unity Flag was presented to Bridie Sweeney, the first ever Tallaght Person of the Year and a dedicated volunteer at the Vincent's shop in Tallaght Village, in recognition of her extensive community work. Bridie, honored in 1984 during the inaugural Tallaght Person of the Year awards, was acknowledged by the Tallaght Community Council for her enduring energy and commitment to volunteering. Tara De Buitléar, TCC’s volunteer PRO, highlighted Bridie's continuous community focus and her significant role at St Vincent de Paul. The flag is intended as a symbol of Tallaght’s identity and community spirit. It is now displayed proudly in Vincent’s shop, joining many local businesses and groups that embrace and fly the Tallaght flag with pride.[52]

Description

editThe Tallaght Unity Flag, prominently features a red deer, symbolising strength and resilience, with its leaping posture suggesting forward movement and progress, embodying the spirit of the Tallaght people. The green triangle in the lower left corner represents the lush landscapes and natural beauty of Tallaght, a color historically associated with Ireland, signifying growth and harmony. The flag also includes three blue, eight-pointed stars on the right side, inspired by the design captured during the Battle of Tallaght in 1867, representing endurance and the historical struggles of the community, with blue emphasising inclusivity and unity. The white background provides a neutral canvas, symbolising peace and unity, reflecting the community’s aspirations for harmony and collaboration.[53]

People

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Notable people from Tallaght include:

- Rhasidat Adeleke (2002-), Irish Athlete[54]

- Dessie Baker, football player

- Richie Baker, football player

- Richard Baneham, Two Oscars for Visual Effects

- Graham Barrett, football player

- Ciarán Bourke, Former member of The Dubliners

- Stephen Bradley, football player and manager

- Jason Byrne, football player

- Kurtis Byrne, football player

- Mark Byrne (1988-), football player

- Richard Dunne (1979-), football player

- Keith Fahey (1983-), football player

- Alice Furlong, Poet and Activist

- Graham Gartland, football player

- Jason Gavin, football player

- Kojii Helnwein (née Wyatt), model and musician

- Patrick Holohan, mixed martial artist / member of South Dublin County Council

- Evie Hone (1894–1955), artist, buried here

- William Howard Russell (1820–1907), journalist, and possibly the world's first modern war correspondent

- Eddie Hyland, professional Boxer

- Patrick Hyland, professional boxer

- Paul Hyland, professional boxer

- Jafaris (1995-) musician

- Alan Joyce (executive) (1966-), CEO Qantas Airlines

- Robbie Keane (1980-), football player

- Oisín Kelly (1915–1981), artist and sculptor

- Paul Kelly Irish Musician

- Stephen Kenny football manager

- Emmet Kirwan actor and writer

- Eric McGill, football player

- Barry Murphy, football player

- Nucentz, rapper, born here in 1987

- David O'Connor (footballer), football player

- Shane O'Connor (1985), dart player

- Kieran O'Reilly (1979-), actor, musician

- Mark O'Rowe (1970-), playwright

- Tomás Ó Súilleabháin actor, film director

- Al Porter, comedian

- Nicola Pierce, Irish writer and ghost writer

- Elizabeth Rivers Artist

- June Rodgers (b. 1959), comedian

- Lynn Ruane, Senator / activist

- George Otto Simms (1910–1991), Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh, and Primate of All Ireland

- Aidan Turner (1983-), actor (Mitchell in Being Human)

- Katharine Tynan (1861–1931), writer

- Mark Yeates (1985-), football player

- Katie McCabe, football player

See also

editExternal sources

edit- Dublin, Hodges Figgis, 1889; Handcock, William Domville, "The History and Antiquities of Tallaght in the County of Dublin", 2nd edition, revised and enlarged

- "South Dublin County Council history of Tallaght". Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2006.

References

edit- ^ a b c "Census 2022 - F1008 Population by Electoral Divisions in County Dublin, by Birthplace". Central Statistics Office Census 2022 Reports. Central Statistics Office Ireland. August 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ a b Handcock, William Domville (1889). History and Antiquities of Tallaght in the County of Dublin (2nd ed.). Dublin, Ireland.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Tallaght, Dublin, Ireland: County Development Plan 2004-2010, p. 78

- ^ "Search - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

- ^ "Tallaght City | South Dublin County Council". Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Annals of the Four Masters, M2820.1". Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Annals of the Four Masters". Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ "And we will go hunting to Gleann na Smol". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Feastdays of the Saints, 2006; Ó Riain, Pádraig

- ^ "Rua Red info". Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "History of Tallaght" (PDF). South Dublin County Council. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Multitext - Flag captured from the Fenians at Tallaght, March 1867 Archived 2015-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "As it Happened: Shamrock Rovers 0-3 Rubin Kazan". RTÉ News. 15 September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ a b Office of Public Works, The (31 December 2017). "Flood Risk Management - County Summary, Dublin" (PDF). Flood Information (Ireland). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ Dublin City Council (31 May 2018). "River Dodder Catchment Flood Risk Assessment & Management Study". Dublin City Council. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

There are a number of tributaries draining into the River Dodder with the significant ones being the Tallaght Stream, ...

- ^ "Consultation: Tallaght" (PDF). busconnects.ie. Dublin Bus. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Airport Metro link plan suspended". Irish Independent. 25 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "CSO - Census: Census Startpage". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 24 August 2013..

- ^ "Search - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Census data by traditional Civil Parish of Tallaght area". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Tallaght Stadium - Building Recommences May 2008 Archived May 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Shamrock Rovers F.C. Published on 07-05-08. Retrieved on 14-05-08.

- ^ Shamrock Rovers F.C Archived 2008-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dáil Éireann Members' Directory". Houses of the Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Coláiste de hÍde". Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Tallaght Schools". Tallaght 4 Kids. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ "Institute of Technology, Tallaght : Complete Course List". Institute of Technology Tallaght. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ McDonnell, Daniel (30 October 2010). "Twigg writes new chapter in Rovers' history". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 1 November 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "How the title was won". The Irish Times. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "Shamrock Rovers retain Irish title". UEFA.com. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "O'Neill hails back-to-back champions". Irish Examiner. 26 October 2011. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ "St Maelruans FC Website". Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Dublin Mountains Way | Dublin Mountains Way | Dublin Mountains Partnership". Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Brisk wind blows riders through Tallaght in a flash Tallaght". The Irish Times. 7 July 1998. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Home". tallaghtswimteam.com.

- ^ "Tallaght Theatre". tallaghttheatre.com. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ "Civic Theatre". Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Rua Red". Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ "Tallaght Young Filmmakers - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Gaelphobal Thamhlachta - Baile". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Baile". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "The History of SCOIL CHAITLÍN MAUDE - Scoil Chaitlin Maude". Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Coláiste de hÍde". Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "€50,000 grant for Irish language and cultural centre in village - Echo.ie". 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "€150,000 ceadaithe d'Ionad Gaeilge i dTamhlacht ina mbeidh 'caifé Gaelach', siopa leabhar agus amharclann – Tuairisc.ie". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "South Dublin County, Ireland". Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "South Dublin County, Ireland". Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ "South Dublin County, Ireland". Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "South Dublin County, Ireland". Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Flag Protocol - Tallaght Flag". Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Unity Flag of Tallaght hoisted high over The Dragon Inn - Echo.ie". 6 April 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Molloy's proudly fly the Unity Flag outside the pub - Echo.ie". 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ a b O'Flaherty, Aideen (31 March 2022). "Unity Flag Presented to First Tallaght Person of the Year". The Echo. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Tallaght Flag: The Unity Flag - Tallaght Together". Litter Mugs. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ O'Riordan, Ian (29 July 2017). "Three reasons to be cheerful for the future of Irish athletics Gina Akpe-Moses, Patience Jumbo-Gula and Rhasidat Adeleke represent new generation". The Irish Times. Retrieved 1 November 2018.