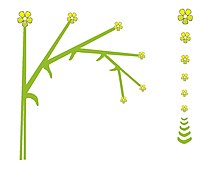

Sympodial growth is a bifurcating branching pattern where one branch develops more strongly than the other, resulting in the stronger branches forming the primary shoot and the weaker branches appearing laterally.[1] A sympodium, also referred to as a sympode or pseudaxis, is the primary shoot, comprising the stronger branches, formed during sympodial growth. The pattern is similar to dichotomous branching; it is characterized by branching along stems or hyphae.[1]

In botany, sympodial growth occurs when the apical meristem is terminated and growth is continued by one or more lateral meristems, which repeat the process. The apical meristem may be consumed to make an inflorescence or other determinate structure, or it may be aborted.

Types

editIf the sympodium is always formed on the same side of the branch bifurcation, e.g. always on the right side, the branching structure is called a helicoid cyme or bostryx.[1]

If the sympodium occurs alternately, e.g. on the right and then the left, the branching pattern is called a scorpioid cyme or cincinus (also spelled cincinnus).

Leader displacement may result: the stem appears to be continuous, but is in fact derived from the meristems of multiple lateral branches, rather than a monopodial plant whose stems derive from one meristem only.[2]

Dichotomous substitution may result: two equal laterals continue the main growth.

In orchids

editIn some orchids, the apical meristem of the rhizome forms an ascendent swollen stem called a pseudobulb, and the apical meristem is consumed in a terminal inflorescence. Continued growth occurs in the rhizome, where a lateral meristem takes over to form another pseudobulb and repeat the process. This process is evident in the jointed appearance of the rhizome, where each segment is the product of an individual meristem, but the sympodial nature of a stem is not always clearly visible.