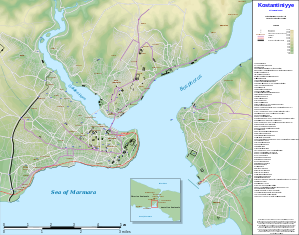

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most notably the Galata Bridge. The medieval citadel of Galata was a colony of the Republic of Genoa between 1273 and 1453. The famous Galata Tower was built by the Genoese in 1348 at the northernmost and highest point of the citadel. Galata is now a quarter within the district of Beyoğlu in Istanbul.

Etymology

editThere are several theories concerning the origin of the name Galata. The Greeks believe that the name comes either from Galatai (meaning "Gauls"), as the Celtic tribe of Gauls (Galatians) were thought to have camped here during the Hellenistic period before settling into Galatia in central Anatolia;[citation needed] or from galatas (meaning "milkman"), as the area was used by shepherds for grazing in the Early Medieval (Byzantine) period.[citation needed] According to another hypothesis it is a variant of the Italian word calata, which means "a section of the docks of the ports intended for the mooring of merchant ships, for the direct embarkation or disembarkation of goods or passengers, for the temporary storage of goods and marine equipment",[1] since the neighborhood was for centuries a Genoese colony. The name Galata has subsequently been given by the city of Genoa to its naval museum, Galata - Museo del mare, which was opened in 2004.

History

editRoman and Byzantine periods

editIn historic documents, Galata is often called Pera, which comes from the old Greek name for the place, Peran en Sykais, literally "the Fig Field on the Other Side."

The quarter first appears in Late Antiquity as Sykai or Sycae. By the time the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae was compiled in ca. 425 AD, it had become an integral part of the city as its 13th region. According to the Notitia, it featured public baths and a forum built by Emperor Honorius (r. 395–423), a theatre, a porticoed street and 435 mansions. It is also probable that the settlement was enclosed by walls in the 5th century.[2] Sykai received full city rights under Justinian I (r. 527–565), who renamed it Iustinianopolis, but declined and was probably abandoned in the 7th century. Only the large tower, Megalos Pyrgos (the kastellion tou Galatou) which controlled the northern end of the sea chain that blocked the entrance to the Golden Horn remained.[2] Galata Tower (Christea Turris) was built in 1348 at the northern apex of the Genoese citadel.

In the 11th century, the quarter housed the city's Jewish community, which came to number some 2,500 people.[2] In 1171, a new Genoese settlement in the area was attacked and nearly destroyed.[3] Despite Genoese averments that Venice had nothing to do with the attack, the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r. 1143–1180) used the attack on the settlement as a pretext to imprison all Venetian citizens and confiscate all Venetian property within the Byzantine Empire.[3] The kastellion and the Jewish quarter were seized and destroyed in 1203 by the Catholic crusaders during the Fourth Crusade, shortly before the sack of Constantinople.[2]

In 1233, during the subsequent Latin Empire (1204–1261), a small Catholic chapel dedicated to St. Paul was built in place of a 6th-century Byzantine church in Galata.[4] This chapel was significantly enlarged in 1325 by the Dominican friars, who officially renamed it as the Church of San Domenico,[5] but local residents continued to use the original denomination of San Paolo.[6] In 1407, Pope Gregory XII, in order to ensure the maintenance of the church, conceded indulgences to the visitors of the Monastery of San Paolo in Galata.[7] The building is known today as the Arap Camii (Arab Mosque) because a few years after its conversion into a mosque (between 1475 and 1478) under the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II with the name Galata Camii (Galata Mosque; or alternatively Cami-i Kebir, i.e. Great Mosque), it was given by Sultan Bayezid II to the Spanish Moors who fled the Spanish Inquisition of 1492 and came to Istanbul.

In 1261, the quarter was retaken by the Byzantines, but Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282) granted it to the Genoese in 1267 in accordance with the Treaty of Nymphaeum. The precise limits of the Genoese colony were stipulated in 1303, and they were prohibited from fortifying it. The Genoese however disregarded this, and through subsequent expansions of the walls, enlarged the area of their settlement.[2] These walls, including the mid-14th-century Galata Tower (originally Christea Turris, "Tower of Christ", and completed in 1348) survived largely intact until the 19th century, when most were dismantled in order to allow further urban expansion towards the northern neighbourhoods of Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, and beyond.[9] At present, only a small portion of the Genoese walls are still standing, in the vicinity of the Galata Tower.

With its design modeled after the 13th century wing of the Palazzo San Giorgio in Genoa,[10] the Genoese Palace was built by the Podestà of Galata, Montano De Marini.[8][11] It was known as the Palazzo del Comune (Palace of the Municipality) in the Genoese period and was initially built in 1314, damaged by fire in 1315 and repaired in 1316.[11][12]

The building's appearance remained largely unchanged until 1880, when its front (southern) façade on Bankalar Caddesi (facing the Golden Horn), together with about two-thirds of the building,[13][14] was demolished for constructing the street's tramway line.[14][15] The front façade was later reconstructed in the 1880s with a different style[14] and became a 5-floor office building named Bereket Han,[15] while its rear (northern) façade on Kart Çınar Sokak (and the remaining one-third of the palace building)[13][14] has retained the materials and design of the original structure, but needs restoration.[11][14][15][16] Bankalar Caddesi has rows of Ottoman-era bank buildings, including the headquarters of the Ottoman Central Bank, which is today the Ottoman Bank Museum. Several ornaments that were originally on the façade of the Genoese Palace were used to embellish these 19th-century bank buildings in the late Ottoman period.

Ottoman period

editWhen Constantinople fell to Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453, the neighborhood was mostly inhabited by Genoese and Venetian Catholics, though there were also some Greek, Armenian and Jewish residents. The Christian residents of Galata maintained a formal neutrality during the Ottoman siege, neither siding with the Sultan, nor openly against him. One modern historian, Halil İnalcık, has estimated (based on a census from 1455) that around 8% of Galata's population fled after the city fell.[17]

In the 1455 census it is recorded that Jews primarily resided in the Fabya quarter and Samona (which is in the vicinity of present-day Karaköy). Though the Greek-speaking Jews of Galata appear to have retained their homes after the conquest, there are no Jewish households recorded in Galata by 1472, a situation that remained unchanged until the mid-16th century.[18]

Contemporary accounts differ about the course of events that took place in Galata during the Ottoman conquest in 1453. By some accounts, those who remained in Galata surrendered to the Ottoman fleet, prostrating themselves before the Sultan and presenting to him the keys of the citadel. This account is fairly consistent in records from Michael Ducas and Giovanni Lomellino; but according to Laonikos Chalkokondyles, the Genoese mayor made the decision to surrender before the fleet arrived in Galata and relinquished the keys to the Ottoman commander Zagan Pasha, not the Sultan. One eyewitness, Leonard of Chios, describes the flight of Christians from the city:[19]

"Those of them who did not manage to board their ships before the Turkish vessels reached their side of the harbor were captured; mothers were taken and their children left, or the reverse, as the case might be; and many were overcome by the sea and drowned in it. Jewels were scattered about, and they preyed on one another without pity."

According to Ducas and Michael Critobulus, the population was not harmed by Zaganos Pasha's forces, but Chalkokondyles does not mention this good conduct, and Leonard of Chios says the population acted against orders from Genoa when they agreed to accept servitude for their lives and property to be spared. Those who fled had their property confiscated; however, according to Ducas and Lomellino, their property was restored if they returned within three months.[20]

Morisco who were expelled from Spain settled in Galata around 1609–1620, their descendants intermingled with the locals.[21]

Galata and Pera in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a part of the Municipality of the Sixth Circle (French: Municipalité du VIme Cercle), established under the laws of 11 Jumada al-Thani (Djem. II) and 24 Shawwal (Chev.) 1274, in 1858; the organisation of the central city in the city walls, "Stamboul" (Turkish: İstanbul), was not affected by these laws. All of Constantinople was in the Prefecture of the City of Constantinople (French: Préfecture de la Ville de Constantinople).[22]

The Camondo Steps, a famous pedestrian stairway designed with a unique mix of the Neo-Baroque and early Art Nouveau styles, and built in circa 1870–1880 by the renowned Ottoman-Venetian Jewish banker Abraham Salomon Camondo, is also located on Bankalar Caddesi.[23] The seaside mansion of the Camondo family, popularly known as the Camondo Palace (Kamondo Sarayı),[24] was built between 1865 and 1869 and designed by architect Sarkis Balyan.[25][26] It is located on the northern shore of the Golden Horn, within the nearby Kasımpaşa quarter to the west of Galata. It later became the headquarters of the Ministry of the Navy (Bahriye Nezareti)[25][26] during the late Ottoman period, and is currently used by the Turkish Navy as the headquarters of the Northern Sea Area Command (Kuzey Deniz Saha Komutanlığı).[24][25][26] The Camondo family also built two historic apartment buildings in Galata, both of which are named Kamondo Apartmanı: the older one is located at Serdar-ı Ekrem Street near Galata Tower and was built between 1861 and 1868;[24] while the newer one is located at the corner between Felek Street and Hacı Ali Street and was built in 1881.[27]

Galatasaray S.K., one of the most famous football clubs of Turkey, gets its name from this quarter and was established in 1905 in the nearby Galatasaray Square in Pera (now Beyoğlu), where Galatasaray High School, formerly known as the Mekteb-i Sultani, also stands. Galatasaray literally means Galata Palace.[28]

In the early 20th century, Galata housed embassies of European countries and sizeable Christian minority groups. At the time, signage in businesses was multilingual. Matthew Ghazarian described Galata in the early 20th century as "a bastion of diversity" which was "the Brooklyn to the Old City’s Manhattan."[29]

Media

editIn the Ottoman era many newspapers in non-Muslim minority and foreign languages were produced in Galata, with production in daylight hours and distribution at nighttime; Ottoman authorities did not allow production of the Galata-based newspapers at night.[30]

Gallery

edit-

Surviving section of the Walls of Galata

-

Another surviving section of the Walls of Galata

Notable buildings in Galata

edit- Genoese Palace (1314)

- Arap Mosque (Church of San Domenico) (1325)

- Galata Tower (1348)

- Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church of Galata (1391)

- Church of Saint Benoit (1427)

- Zülfaris Synagogue (1823)

- Surp Pırgiç Armenian Catholic Church (1834)

- Church of Saints Peter and Paul (1843)

- Camondo Steps (1880)

- St. George's Austrian High School (1882)

- Imperial Ottoman Bank and Ottoman Tobacco Company (1892)

- Tofre Begadim Synagogue (1894)

- Ashkenazi Synagogue (1900)

- British Seaman's Hospital (1904)

- Italian Synagogue (1931)

- Neve Shalom Synagogue (1951)

Notable natives and residents of Galata

editSee also

editReferences and notes

edit- ^ "Calata". Vocabolario Treccani (in Italian). Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, p. 815, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- ^ a b John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice, First Vintage Books Edition May 1986, p. 104

- ^ Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 79

- ^ Eyice (1955), p. 102

- ^ Janin (1953), p. 599

- ^ Janin (1953), p. 600

- ^ a b "Mural Slabs from Genoese Galata". www.thebyzantinelegacy.com. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, pp. 815–816, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- ^ Palazzo del Comune (1314) in Galata compared to Palazzo San Giorgio (13th century) in Genoa

- ^ a b c "Galata'daki tarihi Podesta Sarayı satışa çıkarıldı". haber7.com. 18 July 2022.

- ^ National inventory of historic buildings: Palace of the Podestà (1314) in Galata Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "The front facade of the Genoese Palace (1314) on Bankalar Caddesi that was demolished in 1880".

- ^ a b c d e "The rear (left) and front (right) façades of the Genoese Palace (1314)". hurriyet.com.tr. Hürriyet. 13 July 2021.

- ^ a b c "Ceneviz Sarayı'nı parça parça çalıyorlar". hurriyet.com.tr. Hürriyet. 13 July 2021.

- ^ Ruins of the Genoese Palace (Podesta Sarayı) in Galata, Istanbul, and the 13th century wing of the Palazzo San Giorgio in Genoa, Italy

- ^ Rozen, Minna (2010). A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul:The Formative Years, 1453-1566. Brill. pp. 12–15.

- ^ Rozen, Minna (2010). A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul:The Formative Years, 1453-1566. Brill. p. 15.

- ^ Rozen, Minna (2010). A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul:The Formative Years, 1453-1566. Brill. p. 13.

- ^ Rozen, Minna (2010). A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul:The Formative Years, 1453-1566. Brill. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Krstić, Tijana (2014). "Moriscos in Ottoman Galata, 1609–1620s". The Expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain. pp. 269–285. doi:10.1163/9789004279353_013. ISBN 9789004279353.

- ^ Young, George (1906). Corps de droit ottoman; recueil des codes, lois, règlements, ordonnances et actes les plus importants du droit intérieur, et d'études sur le droit coutumier de l'Empire ottoman (in French). Vol. 6. Clarendon Press. p. 149.

- ^ "Camondo Steps on the Bankalar Caddesi". Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Kamondo Apartmanı (1868) at Serdar-ı Ekrem Street Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Bahriye Nezareti (Ministry of the Navy) building

- ^ a b c Bahriye Nezareti (Ministry of the Navy) building

- ^ National inventory of historic buildings: Kamondo Apartmanı (1881) between Felek Street and Hacı Ali Street Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Galatasaray Sports Club 2288 Website Archived 2009-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ghazarian, Matthew (13 October 2014). "Ottoman Postcards in a Post-Ottoman World". Baraza. ISSN 2373-1079. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (28 February 2018). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien // Cited: p. 40

Sources

edit- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Eyice, Semavi (1955). Istanbul. Petite Guide a travers les Monuments Byzantins et Turcs (in French). Istanbul: Istanbul Matbaası.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.