This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

Storvindeln (Swedish: Storvindeln) is a lake in Sorsele, Västerbotten County, Lapland, Sweden. It is part of the Ume River catchment area and is flooded by the Vindel River.[1]

| Storvindeln | |

|---|---|

| |

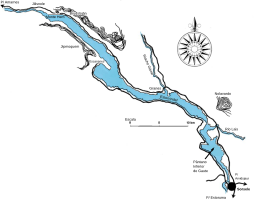

Map of Storvindeln | |

| Location | Sweden, Norrland, Lapland, Västerbotten, Sorsele |

| Coordinates | 65°43′01″N 17°04′59″E / 65.71694°N 17.08306°E |

| Type | Lake |

| Primary inflows | Vindel River |

| Basin countries | Sweden |

| Max. length | 50 metres (160 ft) |

| Surface area | 52 square kilometres (20 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 11.7 metres (38 ft) |

| Max. depth | 35.9 metres (118 ft) |

| Water volume | 0.614 cubic kilometres (0.147 cu mi) |

| Surface elevation | 341.1 metres (1,119 ft) |

The lake has a length of 50 km, an area of 52.1 km2, an average depth of 11.7 m, a maximum depth of 35.9 m, a volume of 0.614 km3, and an elevation of 341.1 m.[2][3] It is flooded by the Vindel.[4]

Along the lake there are high rocks rich in quartz. Jipmoque forms a wall 7 km long and 100 to 150 m high on the southwest side. Below the rocks are very large blocks that may have been shaken by the strong earthquakes that followed soon after the ice melted. On the northeast side of the lake there are whole series of boulders. Not far from Mount Hem, a stream crosses the edge of the lake and forms the Brudslöjan waterfall. At the western end of the lake is the Jillesnåle Chapel, a simple wooden building erected in the early 18th century.[3]

Uses

editThe lake has a natural change of almost five meters in its water level throughout the year. It lowers from winter to spring, when the thaw drains the water into it. It reaches its highest level just before midsummer and then the water drops during the summer and fall. The old boat traffic from Sorsele to Jillesnåle Chapel flowed on the west end of the lake, but with the completion of a road along the lake in the late 1930s, traffic slowed and in the fall of 1938 the last boat passed through. Between Jillesnåle and the village of Amarnas, the road was completed as early as 1923. The Besca waterfall at the outlet between the Lower Gaute Marsh and the Storvindeln was channeled in 1910 to allow boats to reach the lake, causing a drop of half a meter. Since then, the coastal vegetation has adapted to the lower water level, with green belts along the shores moving toward the water. The change in water levels provides wide beaches, where vegetation zonates for the time it is submerged.[3]

Flora and fauna

editIn the Storvindel blooms the rare Jämtland Taraxacum (dandelion), which has become even rarer given the exploitation of all the large lakes below the Vindel. At the bottom of the water during late spring, when the lake is at its lowest point, there are blocky beaches with unique tufts of Caltha and Carex. Due to the influence of ice and frost, blocks and stones can be assembled into rings with the thinner material toward the center. Higher up on the beach, the vegetation becomes denser and full of species, including alders, willows, Carex, herbs, and alpine plants. At the top of the open beaches, Calluna plants abound. The river invades its riparian forest when it is at its highest, and in it grow Filipendula, Angelica, and many other plants. In the eastern part of the lake there are sandy beaches where raigrases, whose discovery in the early 19th century proved that they can grow in regions far from the sea, flourish, as they do in the Gaute Marsh. The discoverer, the Swedish botanist Göran Wahlenberg, published his find in the "Flora Lapponica" of 1812.[3]

In the early 1960s, the Swedish Conservation Council allowed works to be conducted along the flow of the rivers in the area as soon as the original plans were changed so that no expansion would occur in the Vindel upstream of the lake[5] so as not to impact the fish stock. Aimed at fisheries science, the rivers are of great value for the opportunity to study the species.[6] Trout, perch, charr, graylings, pike and whitefish (C. maxillaris, C. widegreni, C. nilssoni and C. peled), etc. live there.[3][7] According to data from the 1970s, about 2.5 tons of fish are caught per year.[8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Storvindeln". VISS Vatteninformationssystem Sverige (in Swedish).

- ^ Gardeström, Johanna (2018). Vindelälven-Juhtatdahka – Biosphere Reserve Application (PDF) (in Swedish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-10.

- ^ a b c d e Storvindeln – Länsstyrelsen Naturvårdsverket (in Swedish). 1997.

- ^ "Storvindeln". VISS Vatteninformationssystem Sverige (in Swedish).

- ^ Vattenkraft och miljö 4 (PDF). Vattenöverledningsutredningen. 1979. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-09.

- ^ Vattenkraft och miljö 4 (PDF). Vattenöverledningsutredningen. 1979. p. 77. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-09.

- ^ Gardeström, Johanna (2018). Vindelälven-Juhtatdahka – Biosphere Reserve Application (PDF) (in Swedish). p. 110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-10.

- ^ Vattenkraft och miljö 4 (PDF). Vattenöverledningsutredningen. 1979. pp. 150–151. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-09.