Stingy Jack O'Lantern, also known as Jack the Smith, Drunk Jack, Flaky Jack or Jack-o'-lantern, is a mythical character sometimes associated with All Hallows Eve while also acting as the mascot of the holiday. The "jack-o'-lantern" may be derived from the character.[1]

| Stingy Jack | |

|---|---|

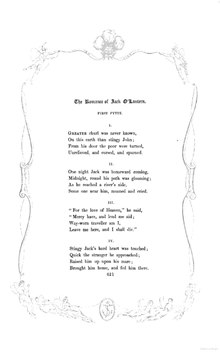

This 1851 poem by Hercules Ellis dramatizes the story of Stingy Jack. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Also known as | Jack-o'-Lantern

Jack the Smith Drunk Jack Flaky Jack Jack of the Lantern |

| Country | Ireland |

History

editAn 1836 edition of the Dublin Penny Journal has Jack help an old man who is revealed to be an angel. To reward him, the angel grants Jack three wishes. He uses these to punish anyone who sits in his chair, takes wood from his tree, or tries to take his cobbling tools, by fixing them to the ground. The angel is disappointed by this and bars Jack from entering Heaven. Jack manages to deflect Satan's messengers who attempt to trick him, and he is condemned to roam the world neither Heaven or Hell.[2]

In 1851, Hercules Ellis presumably wrote and published "The Romance of Jack-o'-Lantern," a romantic poem, in poetry anthology The Rhyme Book.[3] The poem described Stingy Jack's encounters with an angel and with Satan.[3]

Story

editAs the story of Stingy Jack goes,[clarification needed] several centuries ago in Ireland, there lived a drunkard known as Stingy Jack. He was known throughout the land as a deceiver or manipulator. On a fateful night, Satan overheard the tale of Jack's evil deeds and silver tongue. Unconvinced (and envious) of the rumours, the devil went to find out for himself whether or not Jack lived up to his vile reputation.

Typical of Jack, he was drunk and wandering through the countryside at night when he came upon a body on his cobblestone path. The body, with an eerie grimace on its face, turned out to be the devil himself. Jack realized that this was his end; Satan had finally come to collect his malevolent soul. So Jack made a last request: he asked the devil to let him drink ale before he departed to Hell. Finding no reason not to acquiesce the request, Satan took Jack to the local pub and supplied him with many alcoholic beverages. Upon quenching his thirst, Jack asked Satan to pay the tab for the ale, much to his surprise because he didn't carry any money. Jack convinced him to turn himself into a silver coin with which to pay the bartender and change back when he's not looking. Satan did so, impressed upon by Jack's unyielding nefarious tactics. Shrewdly, Jack stuck the now transmogrified Satan (coin) into his pocket, which also contained a crucifix. The crucifix's presence kept the devil from escaping his form. This coerced Satan to agree to Jack's demand: in exchange for his freedom, he had to spare Jack's soul for ten years.

Ten years after the date Jack originally struck his deal, he naturally found himself once again in the devil's presence. Jack happened upon Satan in the same setting as before and he seemingly accepted it was his time to go to Hell for good. As Satan prepared to take him to Hell, Jack asked if he could have one apple to feed his starving belly. Foolishly, Satan once again agreed to this request. As he climbed up the branches of a nearby apple tree, Jack surrounded its base with crucifixes. Satan, frustrated at the fact that he had been entrapped again, demanded his release. As Jack did before, he made a second demand: that he will never take his soul to Hell. Having no choice, the devil agreed and was set free.

Eventually the drinking took its toll on Jack, and he died. Jack's soul prepared to enter heaven through the gates of St. Peter, but he was stopped. Jack was told by God that because of his sinful lifestyle of deceitfulness and drinking, he was not allowed into Heaven. Jack then went down to the Gates of Hell and begged for admission into the underworld. Satan, fulfilling his obligation to Jack, could not take his soul. He gave Jack an ember to light his way. Jack is doomed to roam the world between the planes of good and evil, with only an ember inside a hollowed turnip ("turnip" in this context referring to a large rutabaga) to light his way.[4]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hofherr, Justine; Turchi, Megan (29 October 2014). "The History of The Jack-O-Lantern (& How It All Began With a Turnip)". Boston.com. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Traynor, Jessica (29 October 2019). "The story of Jack-o'-lantern: 'If you knew the sufferings of that forsaken craythur'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ a b Ellis, Hercules (1851). The Rhyme Book. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. pp. 621–627.

- ^ Bachelor, Blane (27 October 2020). "The twisted transatlantic tale of American jack-o'-lanterns". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.