Stevensville (Salish: ɫq̓éɫmlš[3]) is a town in Ravalli County, Montana, United States. The population was 2,002 at the 2020 census.[4]

Stevensville, Montana | |

|---|---|

Stevensville and the Bitterroot River seen from Saint Mary's Peak (2005) | |

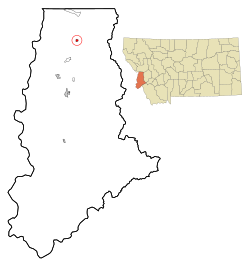

Location of Stevensville, Montana | |

| Coordinates: 46°30′28″N 114°5′36″W / 46.50778°N 114.09333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Ravalli |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Steve Gibson |

| • Body | Stevensville Town Council |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.31 sq mi (3.40 km2) |

| • Land | 1.29 sq mi (3.35 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.05 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,323 ft (1,013 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 2,002 |

| • Density | 1,545.95/sq mi (596.90/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 59870 |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-71200 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2413335[2] |

| Website | www |

Stevensville is officially recognized as the first permanent settlement of non-indigenous peoples in the state of Montana. Forty-eight years before Montana became the nation's 41st state, Stevensville was settled by Jesuit Missionaries at the request of the Bitterroot Salish tribe.

History

editThe Bitterroot Valley is the ancestral homeland of the Bitterroot Salish people. Between 1812 and 1821, the Salish learned about the "powerful medicine" of Christianity and Jesuit missionaries from Iroquois fur traders. In 1831, four young Salish men were dispatched to St. Louis, Missouri, to request "Black Robes" for the tribe.[5] The four Salish men were directed to the home and office of William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) to make their request. At that time Clark was in charge of administering the territory they called home. Through the perils of their trip, two of the Salish died at the home of General Clark. The remaining two Salish men secured a visit with St. Louis Bishop Joseph Rosati, who assured them that missionaries would be sent to the Bitterroot Valley when funds and missionaries were available in the future.

Again in 1835 and 1837 the Bitterroot Salish dispatched men to St. Louis to request missionaries, but to no avail. Finally in 1839 a group of Iroquois and Salish met Father Pierre-Jean De Smet in Council Bluffs. The meeting resulted in Fr. DeSmet promising to fulfill their request for a missionary the following year.

In 1841, DeSmet led a group of Jesuits to the Bitterroot and founded St. Mary's Mission. It became the first permanent white settlement in what is now Montana.[6] Construction of a chapel began immediately, followed by other permanent structures including log cabins. The settlement was the site of many of Montana's "firsts": irrigation, agriculture, ranching, and cattle branding. Father Ravalli, Jesuit priest and physician, arrived at the mission in 1845 and built the first pharmacy.[5]

In 1850 Major John Owen arrived in the valley and set up camp north of St. Mary's.[7] When Blackfeet raids forced the closure of the mission, Owen bought it from the Jesuits and established a trading post called Fort Owen. The Jesuits later returned to the area and built a new church. Both St. Mary's Mission and Fort Owen still have permanent structures that stand in present-day Stevensville, denoting its historical past starting in 1841.[8]

The name of the settlement was changed from St. Mary's to Stevensville in 1864 to honor territorial governor Isaac Stevens.[9] In 1879, G. A. Kellogg platted the townsite.[10] In 1891, the Bitterroot Salish who remained in the valley were forced to remove to the Flathead Indian Reservation.[11] In 1893, Ravalli County was created, and Stevensville became the county seat until 1898, when the town lost the election to Hamilton. More than forty properties in Stevensville are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[10]

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.00 square mile (2.59 km2), of which 0.98 square miles (2.54 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.05 km2) is water.[12]

"Flanked by the Bitterroot and Sapphire mountains, the small, historic town in the Bitterroot Valley offers beautiful views, outdoor recreation, and watchable wildlife."[13] The Bitterroot Mountain Range, just west of Stevensville, is the longest single mountain range in the Rocky Mountains. The Bitterroot River runs along the eastern border.

Climate

editThis climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (rarely humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold) winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Stevensville has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.[14]

| Climate data for Stevensville, Montana (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1911–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

70 (21) |

80 (27) |

88 (31) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

98 (37) |

87 (31) |

74 (23) |

65 (18) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.6 (1.4) |

38.3 (3.5) |

49.6 (9.8) |

58.0 (14.4) |

67.5 (19.7) |

74.8 (23.8) |

85.3 (29.6) |

83.9 (28.8) |

73.6 (23.1) |

58.0 (14.4) |

42.5 (5.8) |

33.1 (0.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.8 (−2.9) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

38.0 (3.3) |

45.0 (7.2) |

53.2 (11.8) |

60.1 (15.6) |

67.1 (19.5) |

65.6 (18.7) |

57.0 (13.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

45.6 (7.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18.9 (−7.3) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

32.0 (0.0) |

38.9 (3.8) |

45.4 (7.4) |

49.0 (9.4) |

47.2 (8.4) |

40.4 (4.7) |

32.1 (0.1) |

24.5 (−4.2) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

32.9 (0.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −36 (−38) |

−37 (−38) |

−19 (−28) |

2 (−17) |

15 (−9) |

27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

27 (−3) |

7 (−14) |

−3 (−19) |

−28 (−33) |

−36 (−38) |

−37 (−38) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.00 (25) |

0.92 (23) |

0.77 (20) |

0.93 (24) |

1.45 (37) |

1.59 (40) |

0.83 (21) |

0.81 (21) |

0.84 (21) |

1.04 (26) |

1.15 (29) |

1.12 (28) |

12.45 (316) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.0 (10) |

3.0 (7.6) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.6 (4.1) |

6.8 (17) |

17.1 (43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.4 | 7.6 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 100.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 9.4 |

| Source: NOAA[15][16] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 47 | — | |

| 1900 | 346 | — | |

| 1910 | 796 | 130.1% | |

| 1920 | 744 | −6.5% | |

| 1930 | 692 | −7.0% | |

| 1940 | 703 | 1.6% | |

| 1950 | 772 | 9.8% | |

| 1960 | 784 | 1.6% | |

| 1970 | 829 | 5.7% | |

| 1980 | 1,207 | 45.6% | |

| 1990 | 1,221 | 1.2% | |

| 2000 | 1,553 | 27.2% | |

| 2010 | 1,809 | 16.5% | |

| 2020 | 2,002 | 10.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[17][4] | |||

2010 census

editAs of the census[18] of 2010, there were 1,809 people, 836 households, and 455 families living in the town. The population density was 1,845.9 inhabitants per square mile (712.7/km2). There were 935 housing units at an average density of 954.1 units per square mile (368.4 units/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.0% White, 0.1% African American, 1.0% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 0.6% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.4% of the population.

There were 836 households, of which 24.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.8% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 45.6% were non-families. 40.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 19.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.87.

The median age in the town was 42.3 years. 22.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.3% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.8% were from 25 to 44; 25.1% were from 45 to 64; and 21.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 46.9% male and 53.1% female.

2000 census

editAs of the census[19] of 2000, there were 1,553 people, 652 households, and 385 families living in the town. The population density was 3,008.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,161.5/km2). There were 711 housing units at an average density of 1,377.3 units per square mile (531.8 units/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.52% White, 0.26% African American, 1.03% Native American, 0.26% Asian, 0.32% from other races, and 1.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.00% of the population.

There were 652 households, out of which 29.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.0% were married couples living together, 10.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.8% were non-families. 35.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 25.3% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 20.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females there were 89.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.0 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $27,951, and the median income for a family was $34,583. Males had a median income of $29,327 versus $20,729 for females. The per capita income for the town was $14,700. About 10.4% of families and 12.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.3% of those under age 18 and 9.7% of those age 65 or over.

Education

editStevensville Public Schools educates students from kindergarten through 12th grade.[20] Stevensville High School had 383 students enrolled in the 2021–2022 school year.[21] Their team name is the Yellowjackets.[22]

North Valley Public Library is located in Stevensville.[23]

Media

editThe Bitterroot Star is a weekly newspaper owned by Mullen Newspaper Company.

Infrastructure

editStevensville is accessed from U.S. Route 93 by Montana Highway 269. Montana Highway 203 exits town on the northeast.

Stevensville Municipal Airport is a town-owned public-use airport located two miles (3.2 km) northeast of town.[25] The nearest commercial airport is Missoula Montana Airport, 32 miles (51 km) north.

Notable people

edit- Janine Benyus, author

- Tyler Bradt, whitewater kayaker, ran Palouse Falls in 2009

- Edward Catich, author was born in the town

- Huey Lewis, lead singer of Huey Lewis and the News

- Marion Marshall, actress

- Washington J. McCormick, United States Representative from Montana, retired to Stevensville

- George McGovern owned a book store and a summer home in the area

- Lee Metcalf, United States congressman (1953–1961) and senator (1961–1978) from Montana

- Kathleen Meyer, author

- Anthony Ravalli, Jesuit pioneer and founder of western U.S. settlements

References

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Stevensville, Montana

- ^ Tachini, Pete; Louie Adams, Sophie Mays, Mary Lucy Parker, Johnny Arlee, Frances Vanderburg, Lucy Vanderburg, Diana Christopher-Cote (1998). nyoʻnuntn q̓éymin, Flathead Nation Salish dictionary. Pablo, Montana: Bilingual Education Department, Salish Kootenai College. p. 137.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Baumler, Ellen (Spring 2016). "A Cross in the Wilderness: St. Mary's Mission Celebrates 175 Years". Montana The Magazine of Western History. 66 (1): 18–38. JSTOR 26322905. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Historic St. Mary's Mission - Where Montana Began - National Historic Site". www.SaintMarysMission.org. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Major John Owen". mt.gov. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Fort Owen". mt.gov. Archived from the original on September 25, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Stevensville". VisitMt.com. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Aarstad, Rich; Arguimbau, Ellen; Baumler, Ellen; Porsild, Charlene L.; Shovers, Brian (2009). Montana Place Names from Alzada to Zortman. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0975919613. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Bigart, Robert (Spring 2010). "'Charlot loves his people': The Defeat of Bitterroot Salish Aspirations for an Independent Bitterroot Valley Community". Montana The Magazine of Western History. 60 (1): 24–94. JSTOR 25701716. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Official State of Montana Department of Tourism, "Towns and Cities: Stevensville"". VisitMt.com. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Stevensville, Montana Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Stevensville Public Schools". Stevensville Public Schools. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Stevensville High School". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ "Member Schools". Montana High School Association. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "North Valley Public Library". North Valley Public Library. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "KKVU". FCC. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ "32S Stevensville". FAA. Retrieved October 27, 2023.