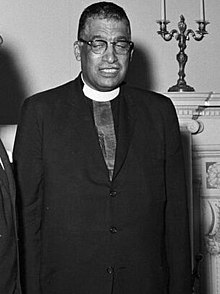

Stephen Gill Spottswood (July 18, 1897 – December 2, 1974)[1] was a religious leader and civil rights activist known for his work as bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) and chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Stephen Spottswood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chair of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People | |

| In office 1961–1975 | |

| Preceded by | Robert C. Weaver |

| Succeeded by | Margaret Bush Wilson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Stephen Gill Spottswood July 18, 1897 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | December 2, 1974 (aged 77) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education | Albright College (BA) Gordon College (ThB) Yale University (DDiv) |

Bishop Spottswood's papers are currently archived at the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University (not Dillard University).

Early life and family

editSpottswood was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the only child of Mary Elizabeth and Abraham Lincoln Spottswood.[1][2] He attended Cambridge Rindge and Latin School and then Freeport High School in Maine. He went on to Albright College, earning a B.A. in history in 1917; Gordon Divinity School; and Yale Divinity School, where he earned his doctorate.[2][3]

Religious leadership

editShortly after finishing his undergraduate work, Spottswood was named assistant pastor of the First Evangelical United Brethren Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, followed soon after by an appointment with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ).[2] Between the time he received his Th.B. from Gordon in 1919 through 1936, he served in leadership positions at several churches around the country: First AMEZ Church of Lowell in Lowell, Massachusetts, which he also founded; Green Memorial AMEZ Church in Portland, Maine; Varick Memorial AMEZ Church in New Haven, Connecticut; Goler Memorial AMEZ Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Jones Tabernacle AMEZ Church in Indianapolis, Indiana; St. Luke AMEZ Church in Buffalo, New York; and John Wesley AMEZ Church in Washington, D.C.[1][2]

While in Washington, in 1952, he was elected the 58th bishop of the AMEZ.[4] He also served in various episcopal districts around the country through the 1950s and 1960s.[2][3]

Civil rights activism and involvement with NAACP

editSpottswood joined the NAACP in 1919 and was an active voice for racial equality throughout his adult life.[4] Though he would later play a more conventional leadership position, he also participated in a number of public protests, including sit-ins, boycotts, and pickets, believing that those activities which had economic impact were among the most effective for bringing about change.[2][4]

He became president of the NAACP's Washington branch in 1947 and was elected to the national board of the NAACP in 1955, vice-president in 1959, and finally chairman in 1961, a post he held until 1975. He became well known for his harsh criticism of those opposing civil rights issues and of the Nixon administration in particular.[5]

Keynote address at the 1970 NAACP convention

editSpottswood earned a reputation as an outspoken critic of racial injustice and several times attracted press coverage for his political censures. At the 61st annual convention of the NAACP, held in Cincinnati in 1970, the 72-year-old Spottswood delivered a controversial and widely publicized keynote address covering a number of topics. He warned people not to trust segregationist Alabama governor and presidential candidate George Wallace, who had begun to speak of a more positive stance on racial issues.[6] He also condemned racism in law enforcement, stating that "killing black Americans has been the 20th-century pastime of our police".[1]

His most prominent criticism was directed at Richard Nixon and his administration's treatment of African-Americans, calling it "anti-Negro".[7][8] Spottswood said it was "the first time since 1920 that the national Administration has made it a matter of calculated policy to work against the needs and aspirations of the largest minority of its citizens".[8][9] In particular, he criticized Nixon's cutting of various social programs related to housing, poverty, and equal opportunity, and accused Republicans of seeking to undermine the Voting Rights Act and desegregation of schools.[10] On Nixon's anti-busing stance, he said, "Nixon does not want to abolish busing for the 20 million children bused every day for educational and social purposes. He just wants to keep 2.7 million children from being bused for desegregation purposes".[6] He went on to declare that the NAACP, which had traditionally been viewed as nonpartisan, "considers itself in a state of war against President Nixon".[9][11][12]

Following the convention, Spottswood drew "staunch support from the Negro press as a whole", according to The Crisis, which aggregated and republished many of the news pieces, while "there was division among the remainder of the press ranging from hearty approval to disparagement".[7] Presidential special counsel Leonard Garment responded to Spottswood's allegations about the Voting Rights Act and school desegregation, calling them "unfair and disheartening".[8][10][13] Fellow AMEZ bishop C. Eubank Tucker said Spottswood's accusations were "both unjustified and unwarranted" and went on to charge the NAACP with receiving funds from the National Democratic Party. The NAACP issued a statement denying Tucker's corruption accusation and speculated about legal remedy while pointing out his longtime "loyalty to the Republican Party".[14] Spottswood replied to Tucker by calling him a "falsifier", expressing he did not wish to call his associate a liar, and to his other critics he defended his "anti-Negro" statement, insisting it was "sustained by the record".[7][15]

At the following year's convention, Spottswood used his keynote address to soften the NAACP's stance on Nixon, admitting that his administration "has taken certain steps and has announced policies in certain phases of the civil rights issue which have earned cautious and limited approval among black Americans",[16] who, he cautioned, should not "live in a vacuum as long as he's President".[9] His colleague Roy Wilkins had previously clarified that in the months following Spottswood's 1970 address, Nixon's policies had been "only 95 percent anti-black".[13]

Personal life

editIn 1919 he married Viola Estelle Booker, whom he was with until her death in a fire in 1953.[1] They had one son and four daughters.[2][17] In 1969 he remarried to Mattie Brownita Johnson Elliott.[2]

Spottswood retired from his position as bishop of AMEZ in 1972.[1] He died of cancer on December 2, 1974, at the age of 77.[17] After his death, his papers were donated to the Amistad Research Center at Dillard University.[18]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Aaseng, Nathan (2003). Spottswood, Stephen Gill. Infobase Publishing. pp. 206–207. ISBN 9781438107813. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Murphy, Larry G.; Melton, J. Gordon; Ward, Gary L., eds. (2013). Spottswood, Stephen Gill. Routledge. pp. 721–722. ISBN 9781135513382. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Altman, Susan (1997). Stephen Spottswood. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-3824-4. Archived from the original on 2022-01-04. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc (December 1980). "Stephen Gill Spottwood". The Crisis. 87 (10): 564–565. ISSN 0011-1422. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Spottswood Talk to Be Feature of NAACP Parley". Chicago Tribune. 26 October 1972.

- ^ a b "NAACP blasts Nixon policies". Star-News. 1 July 1974.

- ^ a b c The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc (August 1970). "In the Nation's Press". The Crisis. 77 (7): 276–282. ISSN 0011-1422. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c Company, Johnson Publishing (16 July 1970). "Uneasy Truce Ends; NAACP". Jet. 38 (15): 6. ISSN 0021-5996. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c Caldwell, Earl (6 July 1971). "N.A.A.C.P. Softens Anti-Nixon Stand". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Minchin, Timothy; Salmond, John A. (2011). After the Dream: Black and White Southerners since 1955. University Press of Kentucky. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8131-3999-9. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ Tuck, Stephen G. N. (2010). We Ain't What We Ought to Be: The Black Freedom Struggle From Emancipation. Harvard University Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-674-03626-0. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ "NAACP, unhappy over Nixon's 'anti-Negro' policies, may oppose President's reelection". Star-News. 5 July 1972.

- ^ a b "Wilkins says Nixon still 'anti-black'". The Afro-American. 30 January 1971.

- ^ Thornton, Jeannye (4 July 1970). "Black Bishop: Dems Paying NAACP Heads". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Thornton, Jeannye (4 July 1970). "Black Bishop: Dems Paying NAACP Heads". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Education, Jobs, Housing: Big Issues Facing NAACP Confab". Jet: 12–13. 22 July 1971.

- ^ a b Company, Johnson Publishing (19 December 1974). "NAACP's 'Mr. Outside' Dies of Cancer at Age 77". Jet. 47 (13): 12. ISSN 0021-5996. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Company, Johnson Publishing (January 1976). "Miscellaneous Notes". Black World/Negro Digest. 25 (3): 79. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite journal}}:|last1=has generic name (help)