A steelyard balance, steelyard, or stilyard is a straight-beam balance with arms of unequal length. It incorporates a counterweight which slides along the longer arm to counterbalance the load and indicate its weight. A steelyard is also known as a Roman steelyard or Roman balance.

Structure

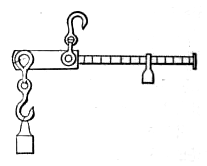

editThe steelyard comprises a balance beam which is suspended from a lever/pivot or fulcrum which is very close to one end of the beam. The two parts of the beam which flank the pivot are the arms. The arm from which the object to be weighed (the load) is hung is short and is located close to the pivot point. The other arm is longer, is graduated and incorporates a counterweight which can be moved along the arm until the two arms are balanced about the pivot, at which time the weight of the load is indicated by the position of the counterweight.[1]

Mechanism

editThe steelyard exemplifies the law of the lever, wherein, when balanced, the weight of the object being weighed, multiplied by the length of the short balance arm to which it is attached, is equal to the weight of the counterweight multiplied by the distance of the counterweight from the pivot.[2]

History

editAccording to Thomas G. Chondros of Patras University, a simple steelyard balance with a lever mechanism first appeared in the ancient Near East over 5,000 years ago.[3] According to Mark Sky of Harvard University, the steelyard was in use among Greek craftsmen of the 5th and 4th centuries BC, even before Archimedes demonstrated the law of the lever theoretically.[4] The Latin name statera comes from the Ancient Greek στατήρ (statḗr). Roman and Chinese steelyards were independently invented around 200 BC. Steelyards dating from AD 100 to 400 have been unearthed in Great Britain. Steelyards and their components have also been excavated from shipwrecks of the Byzantine period in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, such as the 7th-century wreck at Yassi Ada, Turkey, and the mid-first millennium shipwreck at Black Assarca Island, Eritrea. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that the name "steelyard" is derived from steel combined with yard, influenced by an allusion to the Steelyard, the main trading base of the Hanseatic League in London in the 14th century.[5]

Large steelyard balances (known as cart balances), both public and private, were a common feature in agricultural areas in England from the eighteenth century forward. An example of a public cart steelyard remains at Soham, Cambridgeshire, and another is at Woodbridge, Suffolk.[6][7][8]

Function

editSteelyards of different sizes have been used to weigh loads ranging from ounces to tons. A small steelyard could be a foot or less in length and thus conveniently used as a portable device that merchants and traders could use to weigh small ounce-sized items of merchandise. In other cases a steelyard could be several feet long and used to weigh sacks of flour and other commodities. Even larger steelyards were three stories tall and used to weigh fully laden horse-drawn carts.

Scandinavian variant

editA Scandinavian steelyard is a variant which consists of a bar with a fixed weight attached to one end, a movable pivot point, and an attachment point for the object to be weighed at the other end. Once the object to be weighed is attached to its end of the bar, the pivot point, which is frequently a loop at the end of a cord or chain, is moved until the bar is balanced. The bar is calibrated so that the object's weight can be read off directly from the position of the pivot. This type is known in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland .

Gallery

edit-

Scandinavian steelyard balance with moveable pivot

-

Scandinavian steelyard balance

-

Steelyard balance from ancient Rome

-

Swedish steelyard balance with fixed weight and movable, combined hook and handle

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lock, John (1891). Mechanics for Beginners. Vol. One. London: Macmillan. pp. 168–171. OCLC 437255436.

- ^ Whewell, William (1832). First principles of mechanics, with historical and practical illustrations. Cambridge, England: Deighton. p. 35. OCLC 13469803.

- ^ Paipetis, S. A.; Ceccarelli, Marco (2010). The Genius of Archimedes -- 23 Centuries of Influence on Mathematics, Science and Engineering: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Syracuse, Italy, June 8-10, 2010. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 416. ISBN 9789048190911.

- ^ Simon, Emily (11 October 2007). "Even Without Math, Ancients Engineered Sophisticated Machines". Faculty of Arts & Science, Harvard University. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "steelyard, n.2". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Steelyard at the Fountain Inn". Historic England. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ Slight, James; Burn, Robert Scott (1868). "Machines for the products of the soil". In Stephens, Henry (ed.). The Book of Farm Implements & Machines. Edinburgh: Blackwood. pp. 425–428. OCLC 458892190.

- ^ Fairhall, David (2013). East Anglian shores : history, harbours, rivers, fisheries, pubs and architecture. Bloomsbury. p. 123. ISBN 9781472903402.