Stari Grad (Serbian Cyrillic: Стари Град, pronounced [stâːriː ɡrâd]) is a municipality of the city of Belgrade. It encompasses some of the oldest sections of urban Belgrade, thus the name (‘’stari grad’’, Serbian for “old city”). Stari Grad is one of the three municipalities that occupy the very center of Belgrade, together with Savski Venac and Vračar.

Stari Grad

Стари Град (Serbian) | |

|---|---|

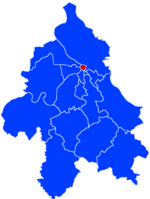

Location of Stari Grad within the city of Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°49′09″N 20°27′26″E / 44.8191359°N 20.4572362°E | |

| Country | |

| City | |

| Status | Municipality |

| Government | |

| • Municipality president | Radoslav Marjanović (SNS) |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.42 km2 (2.09 sq mi) |

| Population (2022) | |

• Total | 44,737 |

| • Density | 8,300/km2 (21,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11000 |

| Area code | +381 11 |

| license plates | BG |

| Website | www.starigrad.org.rs |

History

editEven though some of the oldest sections of Belgrade belong to Stari Grad, the municipality itself is among the latest urban ones formed administratively. It was formed by the merger of the municipality of Skadarlija and part of the municipality of Terazije on January 1, 1957.

Geography

editStari Grad occupies the ending ridge of Šumadija geological bar [self-published source].The cliff-like ridge, where the fortress of Kalemegdan is located, overlooks the Great War Island and the confluence of the Sava river into the Danube, and makes one of the most beautiful natural lookouts in Belgrade. With Novi Beograd, it is one of 2 municipalities of Belgrade (out of 17) which occupy the banks of both major rivers in Belgrade, the Sava and the Danube (Zemun was the third, but when the municipality of Surčin split, Zemun was left with the Danube, and Surčin with the Sava bank).

The municipality of Stari Grad covers an area of just 7 square kilometers (2.7 sq mi) (second smallest in Belgrade, after Vračar) and borders the municipalities of Paliula on the east, Vračar on the south-east and Savski Venac on the south. The Sava makes a border to the municipality of Novi Beograd (west) and the Danube to the municipalities of Zemun (north-west) and the Banat's section of Palilula.

The riverside of the Danube has two distinct artificial bays, the small marina (Marina Dorćol) and the Port of Belgrade.

Neighborhood

editThe neighborhood of Stari Grad is not generally considered by the Belgraders as one single definitive neighborhood. The area which Stari Grad covers is either simply styled "downtown" or by the names of the more established neighborhood which it overlaps: Two parts of Dorćol separated on social-difference and architecture basis, It spreads from the bank of Danube by the Kalemegdan fortress to the Republic Square also known as "The Horse". Downtown Belgrade is most populated area which makes it the heart of the city, it spreads from Terazije down to Despot Stefan Boulevard. Tasmajdan neighborhood is along with Šipka the on the east side of Stari grad next to municipality of Palilula. A lso in this street is located Knez Mihajlova street and the square of the Republic. The most of Belgrade's landmarks are located in this municapality.

This is a list of the neighborhoods in the municipality:

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 67,675 | — |

| 1953 | 81,311 | +3.74% |

| 1961 | 96,517 | +2.17% |

| 1971 | 83,742 | −1.41% |

| 1981 | 73,767 | −1.26% |

| 1991 | 70,791 | −0.41% |

| 2002 | 55,543 | −2.18% |

| 2011 | 48,450 | −1.51% |

| 2022 | 44,737 | −0.72% |

| Source: [2] | ||

Like the other two "old" municipalities of central Belgrade (Savski Venac and Vračar), Stari Grad for decades is a highly depopulating municipality, but being a central municipality and small in area, it remains one of the most densely populated municipalities in Serbia. There were 48,450 inhabitants according to the 2011 census or 6,921/km2 (17,930/sq mi), compared to a population of 96,517 with a density of 13,788/km2 (35,710/sq mi) back in 1961.

Even though residential areas are much densely compact compared to Vračar, the latter is densely populated because almost one third of Stari Grad, even though it is "heart" of Belgrade is not inhabited (mostly the large park of Kalemegdan and the highly industrialized riverside of the Danube, with dozens of factories and spacious hangars and depots). However, a number of people working on the territory of the municipality doubles its own population and makes possible for the municipality of Stari Grad to achieve GDP per capita 6 to 8 times higher than the average in Serbia.

Ethnic structure

editThe ethnic composition of the municipality 2011:[3]

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 43,208 |

| Yugoslavs | 613 |

| Montenegrins | 441 |

| Croats | 268 |

| Macedonians | 203 |

| Gorani | 156 |

| Romani | 116 |

| Muslims | 97 |

| Slovenians | 84 |

| Russians | 68 |

| Albanians | 63 |

| Hungarians | 53 |

| Bosniaks | 40 |

| Romanians | 35 |

| Slovaks | 34 |

| Germans | 31 |

| Bulgarians | 28 |

| Others | 2,912 |

| Total | 48,450 |

The ethnic composition of the municipality 2022:[3]

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 34,962 |

| Yugoslavs | 799 |

| Russians | 447 |

| Montenegrins | 254 |

| Croats | 135 |

| Macedonians | 119 |

| Gorani | 98 |

| Romani | 76 |

| Hungarians | 46 |

| Muslims | 43 |

| Germans | 32 |

| Romanians | 28 |

| Slovenians | 27 |

| Slovaks | 27 |

| Bulgarians | 25 |

| Albanians | 21 |

| Bosniaks | 19 |

| Others | 7,579 |

| Total | 44,737 |

Administration

editRecent presidents of the municipality:

- 1992 – 2000: Jovan Kažić (b. 1937)

- 2000 – 2012: Mirjana Božidarević (b. 1954)

- 2012 – 2016: Dejan Kovačević (b. 1966)

- 2016 – 2020: Marko Bastać (b. 1984)

- 2020 – present: Radoslav Marjanović (b. 1989)

Economy

editThe following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[4]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 60 |

| Mining and quarrying | 32 |

| Manufacturing | 3,192 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 753 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 252 |

| Construction | 1,592 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 7,643 |

| Transportation and storage | 2,704 |

| Accommodation and food services | 4,719 |

| Information and communication | 6,875 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 3,735 |

| Real estate activities | 457 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 7,731 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 6,201 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 3,514 |

| Education | 5,269 |

| Human health and social work activities | 2,136 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 3,074 |

| Other service activities | 2,397 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 9 |

| Total | 62,346 |

Features

editAdministration

editEconomy and tourism

edit- Port of Belgrade; City's general urban plan (GUP) from 1972 projected the removal of the Port of Belgrade and the industrial facilities by 2021. The cleared area was to encompass the Danube's bank from the Dorćol to the Pančevo bridge. At that time, the proposed new locations included the Veliko Selo marsh or the Reva 2 section of Krnjača, across the Danube. When the GUP was revised in 2003, it kept the idea od relocating the port and the industry, and as the new location only Krnjača was mentioned. There was an idea that the already existing port of Pančevo, after certain changes, could become the new Belgrade's port, but the idea was abandoned.[5]

- Large industrial zone on the riverside of the Danube, surrounding the port

- BEKO clothing factory

- Belgrade Fortress with the Kalemegdan park

- Botanical garden of Jevremovac

- Belgrade Zoo

- Prince Michael Street

- Bohemian quarter of Skadarlija

- Aleksandar Palas[6] *****

- Hotel Majestic ****

- Hotel Palace ****

- Le Petit Piaf[7] ***

- Hotel Royal ***

Culture

edit- Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Museum of Applied Arts (Vuka Karadžica 18)

- National Museum of Serbia (Trg republike 1a)

- Residence of Princess Ljubica (Kneza Sime Markovića 3)

- Serbian Orthodox Church Museum[8] (Kralja Petra I 5)

- Military Museum (Kalemegdan)

- Museum of Belgrade Fortress (Kalemegdan)

- Museum of Ethnography (Studentski trg 13)

- Museum of Pedagogy[9] (Uzun Mirkova 14)

- Museum of the City of Belgrade (Zmaj Jovina 1)

- Museum of Theatrical Arts of Serbia (Gospodar Jevremova 19)

- Jewish Historical Museum[10] (Kralja Petra I 71/1)

- Museum of Vuk and Dositej (Gospodar Jevremova 21)

- Museum of Automobiles[11] (Majke Jevrosime 30); the building was constructed in 1929 and was the first purposely built public garage in the city. It was designed by the Russian émigré architect Valery Stashevsky. It was a modern facility for the period, and included the gas station in the front while the hall included the repair shop, had central heating and ventilation. The façade is designed in the way that it simulated a regular residential house. Though it is only a ground-floor hall, it has two-storey windows. There are two pairs of windows on each side of the main entrance and a glass lunette above it. After World War II, the facility was used by the Radio Television Belgrade for their vehicle fleet. Bratislav Petković began parking classic cars in the garage in 1994 and in time it grew into the museum while the building was placed under the state protection.[12] In September 2019 it was announced that the open air garage for the vehicles of the Ministry of the Interior under the Branko's Bridge will be adapted in two museum, one of which will be the relocated Museum of Automobiles. The building in Majke Jevrosime Street, known as the Modern Garage, will be returned to the pre-World War II owners in the process of the Restitution. The larger area will allow for more than 50 cars to be exhibited, which is the number of cars displayed at the present museum.[13] In May 2022 it was announced the museum will probably remain in its present location, as the negotiations with the new building owners are going in the good direction. Renaming after Petković, its collector, was announced for 2024.[14]

- PTT museum (Majke Jevrosime 13); built from 1926 to 1930 and designed by Momir Korunović, with its specific red-white façade, it is considered one of the most beautiful buildings constructed in Belgrade during the Interbellum; it was built as the administrative building for the Post Office company and today it is a postal museum.[15]

As a curiosity, Stari Grad is the location of two shortest streets of Belgrade, Marka Leka and Laze Pačua, which are 45 and 48 meters long, respectively.[16] Despite being in the sole downtown and densely populated urban section, they have no numbers as all the buildings located in them are )numbered from the neighboring streets.

Education

edit- Elementary school "Stari Grad"; founded in 1961 and originally named "1st Proletarian Brigade", with 1,300 pupils it was the largest school in this part of Belgrade. It was among the first schools in Belgrade which got a large library, day care, electronic classrooms, etc. As the population of Stari Grad dwindled, so did the number of pupils. Since the early 2010s, city administration considered to close the school. In March 2016 city announced the closing which provoked opposition from the pupils who organized petition in downtown to keep the school, followed by the joint protests of the pupils, their parents and teachers. The school was preserved for a year, but as the number of pupils fell to 142, in June 2017 city finally decided to resettle the pupils in the neighboring schools and to move the Sports Gymnasium in its building.[17]

Healthcare

editCommunity health center Stari Grad was founded in 1948 as the Polyclinic of the First Raion. It was located at the corner of the Gospodar Jevremova and Kapetan Mišina streets, in the building of the Belgrade Shipping Society. It moved into the large, new building in the Simina Street in 1964. In 2018, it was estimated that municipality has 47,000 inhabitants, but the health center had 82,000 registered patients.[18]

Dva Bela Goluba

editUp to the 1860s, this area was uninhabited.[19] The Hilandarska Street was described as a "dusty road with several gardens".[20] Jovan Kujundžić, a tailor (terzija, tailor of the cloths) had a ground floor house at the modern crossroad of the Makedonska, Svetogorska, Hilandarska and Cetinjska streets. He switched to the catering business and founded a kafana Dva bela goluba ("Two white doves"). Originally, it was a typical road meyhane. The kafana became so famous, that the entire neighborhood and the modern Svetogorska Street, were named after it in 1872.[21] By the end of the 19th century, the neighborhood gradually developed along the central street and became fully urbanized, as a direct, eastern extension of the city's downtown.[19]

At the corner of Hilandarska and Džordža Vašingtona, there was a famous kafana named Kod Sedam Švaba ("Chez Seven Germans"), after German engineers who were working on the construction of the First Town Hospital in the 1860s. Later it was renamed to Vidin-Kapija. Unlike Svetogorska, Hilandarska, as a side street, never became a commercial area, remaining residential with distinguished villas and buildings. They included houses of writer and physician Laza Lazarević, and the largest house of all, the home of Mihailo Jovanović, Metropolitan of Belgrade. His garden, which extended to the north, in time developed in the entire small neighborhood of its own, originally known as Mitropolitova Bašta ("metropolitan's garden"), but in 1924 renamed to Kopitareva Gradina.[20]

The neighborhood became quite affluent. Other well-known residents include Antun Gustav Matoš, Milutin Bojić, Ivo Vojnović, and members of the Nušić family. Architects like Milan Antonijević, Andra Stevanović, Stojan Titelbah, Stojan Veljković, Otto Lorenz and Momčilo Belobrk designed numerous buildings for brothers Antonijević, hockey player Milenko Materni, priest Đoka Cvetković (demolished in the mid 20-th century), merchant Nastas Savić (in 1937), shopkeeping Obradović family (demolished in the 1960s, to make room for electrical substation). Some villas had facades in Bauhaus style, or interior halls in pink marble and fountains. The largest building was a modern Trade School, a bequest of Mrs. Evgenija Kiki.[20]

In the late 1920s, the Artisan Guild purchased the house and the surrounding lot in order to build the Home of the Artisans, which is today the building of the Radio Belgrade. Kujundžić had one condition, that the name is to be preserved. Because of that, above the entrance into the building, the sculptural composition was carved. It shows two persons with an anvil (symbol of artisans), next to the anvil are scissors (symbol of tailors), with two white doves. The kafana was moved to the Bohemian quarter of Skadarlija and the name for the neighborhood fell into oblivion.[21]

The neighborhood remains a location of several important buildings which were declared cultural monuments and protected by law:

- Jevrem Grujić's House (17 Svetogorska St, built 1896, protected 1961)

- House of Dr. Stanoje Stanojević (32 Svetogorska St, built 1899, protected 1984)

- Uroš Predić's Studio (27 Svetogorska St, built 1908, protected 1987)

- Commercial Academy Building (48 Svetogorska St, built 1926, protected 1992)

- Artisans Club Building (2 Hilandarska St, built 1933, protected 1984)

- Building of Ljubomir Miladinović (6 Hilandarska St, built 1938, protected 2001)

International relations

editTwin towns — Sister cities

editStari Grad is twinned with:

- Yermasoyia, Cyprus

- Kotor, Montenegro

- Staré Mesto, Bratislava, Slovakia

- Centar, Skopje, North Macedonia

- Erzsébetváros, Budapest, Hungary

- Belgrade, Namur, Belgium

- Bitola Municipality, Bitola, North Macedonia

- Stari Grad Municipality, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina[22]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Насеља општине Стари Град" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). Stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ a b "ETHNICITY Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ D.B. (3 March 2009). "Uskoro dogovor o vlasništvu nad zemljištem Luke Beograd" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ^ "Aleksandar Palas hotel located in the very heart of Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro". www.aleksandarpalas.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Hotel Le Petit Piaf - Dobrodošli". Petitpiaf.com. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ "Museum of Serbian Orthodox Church". Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ "Pedagogical Museum". Град Београд - Званична интернет презентација - Pedagogical Museum. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ "乳酸菌が生きているとは". Jim-bg.org. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ "Museum of Automobiles". Град Београд - Званична интернет презентација - Museum of Automobiles. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

- ^ Nenad Novak Stefanović (18 January 2019). "Једна кућа једна прича - Гаражирање историје аутомобила" [One house, one story - Garaging of the car history]. Politika-Moja kuća (in Serbian). p. 01.

- ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (13 September 2019). "Ispod Brankovog mosta – muzeji automobila i MUP-a" [Museums of automobiles and Ministry of the Interior under the Branko's Bridge]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (12 May 2022). "Muzej automobila možda ostane na staroj adresi" [Depo has been sMuseum of the Automobiles may remain on its old address]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ Dejan Aleksić (22 April 2018). "Zaboravljeni srpski Gaudi" [Forgotten Serbian Gaudi]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Politika, April 26, 2008, p.30

- ^ A.Jovanović, D.Aleksić (7 June 2017), "OŠ "Stari grad" definitivno se gasi posle 56 godina", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ^ Ana Vuković (25 October 2018). "Седам деценија Дома здравља "Стари град"" [Seven decades of the Health center "Stari grad"]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ a b Irena Sretenović (2015). "Painting Studio of Uroš Predić" (PDF) (in Serbian and English). Belgrade: Cultural Heritage Preservation Institute of Belgrade.

- ^ a b c Goran Vesić (7 October 2022). Кафана "Код седам Шваба" [Kafana "Chez Seven Germans"]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 17.

- ^ a b Dragan Perić (29 October 2017), "Nerandža i "Dva bla goluba"" [Nerandža and "Two white doves"], Politika-Magazin, No. 1048 (in Serbian), p. 25

- ^ "Bratimile se dvije najstarije općine iz Sarajeva i Beograda". Općina Stari Grad. Retrieved 2023-11-27.