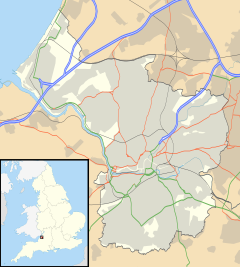

St Pauls (also written St Paul's) is an inner suburb of Bristol, England, lying just northeast of the city centre and west of the M32. It is bounded by the A38 (Stokes Croft), the B4051 (Ashley Road), the A4032 (Newfoundland Way) and the A4044 (Newfoundland Street), although the River Frome was traditionally the eastern boundary before the A4032 was constructed.[1] St Pauls was laid out in the early 18th century as one of Bristol's first suburbs.

History

editIn the 1870s, the Brooks Dye Works opened on the edge of St Paul's and became a major local employer, leading to the construction of terraced houses.[2] Together with migration to Bristol, both from overseas and within Britain, this led to St Paul's becoming a densely populated suburb by the Victorian era.[3]

The area was bomb damaged during World War II. Rebuilding and investment was focused on new housing estates such as Hartcliffe and Southmead rather than St Paul's, and this contributed to a decline in the quality of the area. During the large-scale immigration of the 1950s, many people moved from Jamaica and Ireland, and settled in St Paul's.[4][5]

In 1963 St Paul's became the focus of attention when members of the British African-Caribbean community organised the Bristol Bus Boycott to protest against the racist employment policy of the Bristol Omnibus Company which operated a colour bar, refusing employment to non-white workers as bus crews. This policy was overturned in August of that year after sixty days of protest and the action helped establish the Race Relations Act 1968.[6]

A riot followed a police raid on the Black and White Café in St Paul's on 2 April 1980. The St Paul's riot started when the police entered the café, knowing that the premises was being used for drug dealing. A customer had his trousers ripped and demanded compensation, which the police refused. A crowd outside then refused to allow the police to leave, and when back-up was called a riot started.[7] The riots were quickly blamed on race, but both white and black youths from both Irish and Jamaican backgrounds and some English fought against the police and the problems are thought to have been linked instead to poverty and perceived social injustices, predominantly the Sus law and anti-Irish feelings from IRA activity on the mainland.

In 1990, St Paul's politician Kuomba Balogun, chairman of the Bristol West Labour Party, was reported in the Bristol Evening Post of 2 February, as saying: "We make a public plea to the IRA to consider ways of strongly giving some assistance to the armed wing of the ANC in the same light as Colonel Gaddafi sought to assist in the liberation of the people of Ireland." An early day motion was presented in Parliament calling on him to be expelled from the Labour Party.[8]

This area of the city has also suffered from gun violence, reaching a high point in the early 2000s decade when rival Jamaican Yardie and drug gangs such as the British Aggi Crew fought turf wars over territory.[9] The drugs war between the feuding factions was extinguished following en masse arrests of members of the Yardies and the Aggi Crew, with many of the foreign drug dealers being deported back to Jamaica.[citation needed]

The Black and White Café was closed in March 2005, and has been demolished to make way for houses after a compulsory purchase order. Now[when?] the area is experiencing a positive urban renewal with the St Paul's Unlimited scheme.

Community

editSt Paul's has a large African-Caribbean population. The relative poverty of the area has created a strong community spirit which is shown in the St Pauls Carnival, similar to the Notting Hill Carnival in London. It has been run annually since 1967 except for a hiatus in 2015–2017,[10] and by 2006 attracted an average of 40,000 people each year.[11] The event is a vibrant parade with local primary schools and community groups joining in.[12]

Parks

editThe main parks are St Agnes Park and St Paul's Park, together with Portland and Brunswick squares. Other green spaces include Grosvenor Road Triangle and Dalrymple Road Park. A footbridge over the A4032 allows access to nearby Riverside Park, alongside the Frome.

Architecture

editMany of the buildings in St Paul's are from the Georgian period. Portland Square and St Paul's Church (completed in 1794) are fine examples of Georgian architecture; both were designed by Daniel Hague.[13] The church fell into disuse in 1988, and in 2005 was converted for its present role as the home of Circomedia,[14] a circus school. Edward William Godwin (1833–1886), a famous architect, lived in Portland Square.[citation needed]

Redevelopment plans

editThis section needs to be updated. (June 2024) |

In May 2007, proposals were announced to build about 753,000 square feet (70,000 m2) net of homes, offices and businesses, in the St Paul's area. The development, if approved, may include a 600 ft (180 m), 40-storey, tower next to the M32 motorway as a new entrance to the city. The tower would be a similar shape to the Swiss Re "gherkin" tower in London.[15]

Politics

editSt Pauls is part of the Ashley ward of Bristol City Council, along with St Agnes, St Andrews, Montpelier and St Werburghs.[16] Ashley ward is represented by three elected councillors.[17]

References

edit- ^ "St Pauls". Stories around Bristol’s Bearpit. Bearpit Improvement Group. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "St Pauls Unlimited Community Partnership" (PDF). Voscur. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Plaster, Andrew. "St James Priory". Bristol & Avon Family History Society. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Protest revealed city had its own 'dream'". Bristol Post. No. 27 August 2013. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Beckford, George L.; Levitt, Kari (2000). The George Beckford Papers. Canoe Press. p. 369. ISBN 9789768125408. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ Dresser, Madge (1986). Black and White On the Buses. Bristol: Bristol Broadsides. pp. 47–50. ISBN 0-906944-30-9.

- ^ Bristol Riots with the St Paul's riot at the bottom of the page

- ^ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 8 Feb 1990". Hansard. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Thompson, Tony (9 February 2003). "Britain's most dangerous hard drug den". Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Murray, Robin (4 July 2018). "St Paul's Carnival 2018: Why has it not been on for the past three years?". Bristol Post. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "St Paul's Carnival 2007". letter from the Chairman. Archived from the original (MSWord) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "St Pauls and Its Carnival". St Pauls Carnival. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "St Paul's Church". About Bristol. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "Circomedia". Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 29 June 2006.

- ^ "Tower could spearhead development". BBC News. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Ashley Ward profile" (PDF). Bristol City Council. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "Councillor Finder". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.