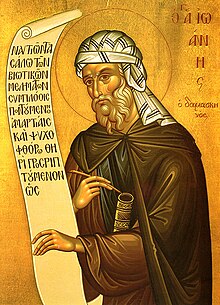

John of Damascus (Arabic: يوحنا الدمشقي, romanized: Yūḥana ad-Dimashqī; Greek: Ἰωάννης ὁ Δαμασκηνός, romanized: Ioánnēs ho Damaskēnós, IPA: [ioˈanis o ðamasciˈnos]; Latin: Ioannes Damascenus; born Yūḥana ibn Manṣūr ibn Sarjūn, يوحنا إبن منصور إبن سرجون) or John Damascene was an Arab Christian monk, priest, hymnographer, and apologist. He was born and raised in Damascus c. 675 AD or 676 AD; the precise date and place of his death is not known, though tradition places it at his monastery, Mar Saba, near Jerusalem on 4 December 749 AD.[5]

John of Damascus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Doctor of the Church, Monk, Teacher of the Faith | |

| Born | c. 675 AD or 676 AD Damascus, Bilad al-Sham, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Died | 4 December 749 AD (aged c. 72–74) Mar Saba, Jerusalem, Bilad al-Sham, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 4 December 27 March (General Roman Calendar, 1890–1969) |

| Attributes | Severed hand, icon |

| Patronage | Pharmacists, Iconographers, theology students Philosophy career |

| Notable work | The Fountain of Knowledge Philosophical Chapters Concerning Heresy An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith |

| Era | Medieval philosophy Byzantine philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism[1] |

Main interests | Law, Christian theology, philosophy, apologetics, criticism of Islam, geometry, Mariology, arithmetic, astronomy, music |

Notable ideas | Icon, dormition/assumption of Mary, Theotokos, perpetual virginity of Mary, mediatrix[2] |

| Influenced | Second Council of Nicaea |

A polymath whose fields of interest and contribution included law, theology, philosophy, and music, he was given the by-name of Chrysorroas (Χρυσορρόας, literally "streaming with gold", i.e. "the golden speaker"). He wrote works expounding the Christian faith, and composed hymns which are still used both liturgically in Eastern Christian practice throughout the world as well as in western Lutheranism at Easter.[6]

He is one of the Fathers of the Eastern Orthodox Church and is best known for his strong defence of icons.[7] The Catholic Church regards him as a Doctor of the Church, often referred to as the Doctor of the Assumption due to his writings on the Assumption of Mary.[8] He was also a prominent exponent of perichoresis, and employed the concept as a technical term to describe both the interpenetration of the divine and human natures of Christ and the relationship between the hypostases of the Trinity.[9] John is at the end of the Patristic period of dogmatic development, and his contribution is less one of theological innovation than one of a summary of the developments of the centuries before him. In Catholic theology, he is therefore known as the "last of the Greek Fathers".[10]

The main source of information for the life of John of Damascus is a work attributed to one John of Jerusalem, identified therein as the Patriarch of Jerusalem.[11] This is an excerpted translation into Greek of an earlier Arabic text. The Arabic original contains a prologue not found in most other translations, and was written by an Arab monk, Michael, who explained that he decided to write his biography in 1084 because none was available in his day. However, the main Arabic text seems to have been written by an unknown earlier author sometime between the early 9th and late 10th century.[11] Written from a hagiographical point of view and prone to exaggeration and some legendary details, it is not the best historical source for his life, but is widely reproduced and considered to contain elements of some value.[12] The hagiographic novel Barlaam and Josaphat is a work of the 10th century[13] attributed to a monk named John. It was only considerably later that the tradition arose that this was John of Damascus, but most scholars no longer accept this attribution. Instead much evidence points to Euthymius of Athos, a Georgian who died in 1028.[14]

Family background

editJohn was born in Damascus, in 675 or 676, to a prominent Damascene Christian Arab family.[15][16][a] His father, Sarjun ibn Mansur, served as an official of the early Umayyad Caliphate. His grandfather, Mansur ibn Sarjun, was a prominent Byzantine official of Damascus, who had been responsible for the taxes of the region during the reign of Emperor Heraclius and also served under Emperor Maurice.[18][19] Mansur seems to have played a role in the capitulation of Damascus to the troops of Khalid ibn al-Walid in 635 after securing favorable conditions of surrender.[18][19] Eutychius, a 10th-century Melkite patriarch, mentions him as one high-ranking official involved in the surrender of the city to the Muslims.[20]

The tribal background of Mansur ibn Sarjun, John's grandfather, is unknown, but biographer Daniel Sahas has speculated that the name Mansur could have implied descent from the Arab Christian tribes of Kalb or Taghlib.[21] The name was common among Syrian Christians of Arab origins, and Eutychius noted that the governor of Damascus, who was likely Mansur ibn Sarjun, was an Arab.[21] However, Sahas also asserts that the name does not necessarily imply an Arab background and could have been used by non-Arab, Semitic Syrians.[21] While Sahas and biographers F. H. Chase and Andrew Louth assert that Mansūr was an Arabic name, Raymond le Coz asserts that the "family was without doubt of Syrian origin";[22] indeed, according to historian Daniel J. Janosik, "Both aspects could be true, for if his family ancestry were indeed Syrian, his grandfather [Mansur] could have been given an Arabic name when the Arabs took over the government."[23] When Syria was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in the 630s, the court at Damascus retained its large complement of Christian civil servants, John's grandfather among them.[18][20] John's father, Sarjun (Sergius), went on to serve the Umayyad caliphs.[18] John of Jerusalem claims that he also served as a senior official in the fiscal administration of the Umayyad Caliphate under Abd al-Malik before leaving Damascus and his position around 705 to go to Jerusalem and become a monk. However, this point is debated within the academic community as there is no trace of him in the Umayyad archives, unlike his father and grandfather. Some researchers, such as Robert G. Hoyland,[24] deny such an affiliation, while others, like Daniel Sahas or the Orthodox historian Jean Meyendorff, suppose that he might have been a lower-level tax administrator, a local tax collector who would not have needed to be mentioned in the archives, but who might not have necessarily been part of the court either.[25][26] In addition, John's own writings never refer to any experience in a Muslim court. It is believed that John became a monk at Mar Saba, and that he was ordained as a priest in 735.[18][27]

Biography

editJohn was raised in Damascus, and Arab Christian folklore holds that during his adolescence, John associated with the future Umayyad caliph Yazid I and the Taghlibi Christian court poet al-Akhtal.[28]

One of the vitae describes his father's desire for him to "learn not only the books of the Muslims, but those of the Greeks as well." From this it has been suggested that John may have grown up bilingual.[29] John does indeed show some knowledge of the Quran, which he criticizes harshly.[30]

Other sources describe his education in Damascus as having been conducted in accordance with the principles of Hellenic education, termed "secular" by one source and "classical Christian" by another.[31][32] One account identifies his tutor as a monk by the name of Cosmas, who had been kidnapped by Arabs from his home in Sicily, and for whom John's father paid a great price. As a refugee from Italy, Cosmas brought with him the scholarly traditions of Latin Christianity. Cosmas was said to have rivaled Pythagoras in arithmetic and Euclid in geometry.[32] He also taught John's orphan friend, Cosmas of Maiuma.

John possibly had a career as a civil servant for the Caliph in Damascus before his ordination.[33]

He then became a priest and monk at the Mar Saba monastery near Jerusalem. One source suggests John left Damascus to become a monk around 706, when al-Walid I increased the Islamicisation of the Caliphate's administration.[34] This is uncertain, as Muslim sources only mention that his father Sarjun (Sergius) left the administration around this time, and fail to name John at all.[24] During the next two decades, culminating in the Siege of Constantinople (717-718), the Umayyad Caliphate progressively occupied the borderlands of the Byzantine Empire. An editor of John's works, Father Le Quien, has shown that John was already a monk at Mar Saba before the dispute over iconoclasm, explained below.[35]

In the early 8th century, iconoclasm, a movement opposed to the veneration of icons, gained acceptance in the Byzantine court. In 726, despite the protests of Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople, Emperor Leo III (who had forced his predecessor, Theodosius III, to abdicate and himself assumed the throne in 717 immediately before the great siege) issued his first edict against the veneration of images and their exhibition in public places.[36]

All agree that John of Damascus undertook a spirited defence of holy images in three separate publications. The earliest of these works, his Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images, secured his reputation. He not only attacked the Byzantine emperor, but adopted a simplified style that allowed the controversy to be followed by the common people, stirring rebellion among the iconoclasts. Decades after his death, John's writings would play an important role during the Second Council of Nicaea (787), which convened to settle the icon dispute.[37]

Leo III reportedly sent forged documents to the caliph which implicated John in a plot to attack Damascus. The caliph then ordered John's right hand be cut off and hung up in public view. Some days afterwards, John asked for the restitution of his hand, and prayed fervently to the Theotokos before her icon: thereupon, his hand is said to have been miraculously restored.[35] In gratitude for this miraculous healing, he attached a silver hand to the icon, which thereafter became known as the "Three-handed", or Tricherousa.[38] That icon is now located in the Hilandar monastery of the Holy Mountain.

Due to his commitment to iconodulism, he was condemned by anathema by the iconoclastic Council of Hieria in 754.[39][40][41] He was later rehabilitated by the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[39]

Veneration

editWhen the name of John of Damascus was inserted in the General Roman Calendar in 1890, it was assigned to 27 March. The feast day was moved in 1969 to the day of John's death, 4 December, the day on which his feast day is celebrated also in the Byzantine Rite calendar,[42] Lutheran Commemorations,[43] and the Anglican Communion and Episcopal Church.[44]

John of Damascus is honored in the Church of England and in the Episcopal Church on 4 December.[45][46]

In 1890, he was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Leo XIII.

List of works

editBesides his purely textual works, many of which are listed below, John of Damascus also composed hymns, perfecting the canon, a structured hymn form used in Byzantine Rite liturgies.[47]

Early works

edit- Three Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images – These treatises were among his earliest expositions in response to the edict by the Byzantine Emperor Leo III, banning the veneration or exhibition of holy images.[48]

Teachings and dogmatic works

edit- The Fountain of Knowledge, The Fountain of Wisdom or The Fount of Knowledge (Koinē Greek: Πηγή Γνώσεως, Pēgē gnōseōs, literally meaning “The Source of Knowledge”), is described as a synthesis and unification of Christian philosophy, ideas and doctrine that was influential in directing the course of medieval Latin thought and that became the principal textbook of Greek Orthodox theology. Divided into three parts the chapters are:

- Philosophical Chapters (Koinē Greek: Κεφάλαια φιλοσοφικά, Kefálea filosofiká) – commonly called "Dialectic", it deals mostly with logic, its primary purpose being to prepare the reader for a better understanding of the rest of the book. Based on the previous work of the late 3rd-century Neoplatonist Porphyry’s Isagoge, an introduction to the logic of Aristotle. The work was notable in that it allowed John of Damascus with information to explain the basic concepts of logic and the rationalisation of God.[49]

- Concerning Heresy (Koinē Greek: Περὶ αἱρέσεων, Perì eréseon, literally meaning “About Heresies”) – Based on the previous work of the Panarion. (Koinē Greek: Πανάριον, derived from Latin panarium, meaning "bread basket") by Epiphanius of Salamis[50][51].The work was notable it allowed John with information about different heresies as well as a model for how to organize a catalogue of heresies. In original 80 religious sects which either classed as organized groups or philosophies, from the time of Adam to the latter part of the fourth century according to Epiphanius. John added twenty heresies that had occurred during his time.[52][49] The last chapter of Concerning Heresy (Chapter 101) deals with the Heresy of the Ishmaelites.[53] Unlike earlier sections devoted to other heresies, which are disposed of succinctly in just a few lines, this chapter runs into several pages. It constitutes one of the first Christian refutations of Islam. In treating of Heresy of the Ishmaelites he vigorously assails the immoral practices of Muhammad and the corrupt teachings inserted in the Quran to legalize the delinquencies of the prophet.[52] Concerning Heresy was frequently translated from Greek into Latin. His manuscript is one of the first Orthodox Christian refutations of Islam which has influenced the Western Roman Catholic Church's attitude on Islam. It was among the first sources representing Muhammad to the West as a "false prophet" and "Antichrist".[54]

- An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Koinē Greek: Ἔκδοσις Ἀκριβὴς τῆς Ὀρθοδόξου Πίστεως, Ékdosis akribès tēs Orthodóxou Písteōs) – a summary of the teachings and dogmatic writings of the Early Church Fathers. More specifically the Cappadocian Fathers (Saint Basil, Saint Gregory of Nazianzus and Saint Gregory of Nyssa) from the 4th century. It incorporates Aristotelian language and demonstrates originality through John's selection of texts and annotations influenced by Antiochene analytical theology. This work, when translated into Oriental languages and Latin, became a valuable resource for both Eastern and Western thinkers, offering logical and theological concepts. Additionally, its systematic style served as a model for subsequent theological syntheses composed by medieval Scholastics. The "Exposition" delves into speculations about the nature and existence of God, giving rise to points of debate among later theologians.This writing was the first work of systematic theology in Eastern Christianity and an important influence on later Scholastic works.[55][49]

Views on Islam

editAs stated above, in the final chapter of Concerning Heresy, John mentions Islam as the Heresy of the Ishmaelites. He is one of the first known Christian critics of Islam. John claims that Muslims were once worshipers of Aphrodite who followed after Muhammad because of his "seeming show of piety," and that Mohammad himself read the Bible and, "likewise, it seems," spoke to an Arian monk that taught him Arianism instead of Christianity. John also claims to have read the Quran, or at least parts of it, as he criticizes the Quran for saying that the Virgin Mary was the sister of Moses and Aaron and that Jesus was not crucified but brought alive into heaven. John further claims to have spoken to Muslims about Mohammad. He uses the plural "we", whether in reference to himself, or to a group of Christians that he belonged to who spoke to the Muslims, or in reference to Christians in general.[56]

Regardless, John claims that he asked the Muslims what witnesses can testify that Muhammad received the Quran from God – since, John says, Moses received the Torah from God in the presence of the Israelites, and since Islamic law mandates that a Muslim can only marry and do trade in the presence of witnesses – and what biblical prophets and verses foretold Muhammad 's coming – since, John says, Jesus was foretold by the prophets and whole Old Testament. John claims that the Muslims answered that Muhammad received the Quran in his sleep. John claims that he jokingly answered, "You're spinning my dreams."[56]

Some of the Muslims, John says, claimed that the Old Testament that Christians believe foretells Jesus' coming is misinterpreted, while other Muslims claimed that the Jews edited the Old Testament so as to deceive Christians (possibly into believing Jesus is God, but John does not say).[56]

While recounting his alleged dialogue with Muslims, John claims that they have accused him of idol worship for venerating the Cross and worshipping Jesus. John claims that he told the Muslims that the black stone in Mecca was the head of a statue of Aphrodite. Moreover, he claims, the Muslims would be better off to associate Jesus with God if they say Jesus is the Word of God and Spirit. John claims that the word and the spirit are inseparable from that in which they exist and if the Word of God has always existed in God, then the Word must be God.[56]

John ends the chapter by claiming that Islam permits polygamy, that Muhammad committed adultery with a companion's wife before outlawing adultery, and that the Quran is filled with stories, such as the She-Camel of God and God giving Jesus an "incorruptible table."[56]

Other works

edit- Against the Jacobites

- Against the Nestorians

- Dialogue against the Manichees

- Elementary Introduction into Dogmas

- Letter on the Thrice-Holy Hymn

- On Right Thinking

- On the Faith, Against the Nestorians

- On the Two Wills in Christ (Against the Monothelites)

- Sacred Parallels (dubious)

- Octoechos (the church's liturgical book of eight tones)

- On Dragons and Ghosts

Arabic translation

editIt is believed that the homily on the Annunciation was the first work to be translated into Arabic. Much of this text is found in Manuscript 4226 of the Library of Strasbourg (France), dating to 885 AD.[57]

Later in the 10th century, Antony, superior of the monastery of St. Simon (near Antioch) translated a corpus of John Damascene. In his introduction to John's work, Sylvestre patriarch of Antioch (1724–1766) said that Antony was monk at Saint Saba. This could be a misunderstanding of the title Superior of Saint Simon probably because Saint Simon's monastery was in ruins in the 18th century.[58]

Most manuscripts give the text of the letter to Cosmas,[59] the philosophical chapters,[60] the theological chapters and five other small works.[61]

In 1085, Mikhael, a monk from Antioch, wrote the Arabic life of the Chrysorrhoas.[62] This work was first edited by Bacha in 1912 and then translated into many languages (German, Russian and English).

Modern English translations

edit- On holy images; followed by three sermons on the Assumption, translated by Mary H. Allies, (London: Thomas Baker, 1898)

- Exposition of the Orthodox faith, translated by the Reverend SDF Salmond, in Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. 2nd Series vol 9. (Oxford: Parker, 1899) [reprint Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1963.]

- Writings, translated by Frederic H. Chase. Fathers of the Church vol 37, (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1958) [ET of The fount of knowledge; On heresies; The orthodox faith]

- Daniel J. Sahas (ed.), John of Damascus on Islam: The "Heresy of the Ishmaelites", (Leiden: Brill, 1972)

- On the divine images: the apologies against those who attack the divine images, translated by David Anderson, (New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1980)

- Three Treatises on the Divine Images. Popular Patristics. Translated by Louth, Andrew. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-88141-245-1. Louth, who also wrote the introduction, was at the University of Durham as Professor of Patristics and Byzantine Studies.

Two translations exist of the 10th-century hagiographic novel Barlaam and Josaphat, traditionally attributed to John:

- Barlaam and Ioasaph, with an English translation by G.R. Woodward and H. Mattingly, (London: Heinemann, 1914)

- The precious pearl: the lives of Saints Barlaam and Ioasaph, notes and comments by Augoustinos N Kantiotes; preface, introduction, and new translation by Asterios Gerostergios, et al., (Belmont, MA: Institute for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 1997)

See also

editNotes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Byzantine Empire: The age of Iconoclasm: 717–867 – britannica.com

- ^ Mary's Pope: John Paul II, Mary, and the Church by Antoine Nachef (1 September 2000) ISBN 1-58051-077-9 pages 179–180

- ^ On the Aristotelian Heritage of John of Damascus Joseph Koterski, S .J

- ^ O'Connor, J.B. (1910). St. John Damascene. In The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 30 July 2019 from New Advent: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08459b.htm

- ^ M. Walsh, ed. Butler's Lives of the Saints (HarperCollins Publishers: New York, 1991), p. 403.

- ^ Lutheran Service Book (Concordia Publishing House, St. Louis, 2006), pp. 478, 487.

- ^ Aquilina 1999, p. 222

- ^ Rengers, Christopher (2000). The 33 Doctors of the Church. Tan Books. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-89555-440-6.

- ^ Cross, F.L (1974). "Cicumincession". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ O'Connor, J.B. (1910) "John of Damascus was the last of the Greek Fathers. His genius was not for original theological development, but for compilation of an encyclopedic character. In fact, the state of full development to which theological thought had been brought by the great Greek writers and councils left him little else than the work of an encyclopedist; and this work he performed in such manner as to merit the gratitude of all succeeding ages". In Orthodox Christianity, the concept of "fathers of the Church" is used somewhat more loosely, with no exhaustive list or end date, with a number of theologians younger than John Damascene generally included.

- ^ a b Sahas 1972, p. 32

- ^ Sahas 1972, p. 35

- ^ R. Volk, ed., Historiae animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (Berlin, 2006)

- ^ Barlaam and Ioasaph, John Damascene, Loeb Classical Library 34, at LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY ISBN 978-0-674-99038-8

- ^ Bowersock, Glen Warren (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- ^ Griffith 2001, p. 20

- ^ Shukurov, Rustam (2024). Byzantine Ideas of Persia, 650–1461. Routledge. p. 139.

- ^ a b c d e Brown 2003, p. 307

- ^ a b Janosik 2016, p. 25

- ^ a b Sahas 1972, p. 17

- ^ a b c Sahas 1972, p. 7

- ^ Janosik 2016, p. 26

- ^ Janosik 2016, pp. 26–27

- ^ a b Hoyland 1996, p. 481

- ^ Sahas, Daniel John (7 September 2023). Byzantium and Islam: collected studies on Byzantine-Muslim encounters. Brill. p. 335. ISBN 978-90-04-47044-6.

- ^ Meyendorff, John (1964). "Byzantine Views of Islam". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 18: 113–132. doi:10.2307/1291209. JSTOR 1291209.

If we are to believe this traditional account, the information that John was in the Arab administration of Damascus under the Umayyads and had, therefore, a first-hand knowledge of the Arab Moslem civilization, would, of course, be very valuable. Unfortunately, the story is mainly based upon an eleventh- century Arabic life, which in other respects is full of incredible legends. Earlier sources are much more reserved.

- ^ McEnhill & Newlands 2004, p. 154

- ^ Griffith 2001, p. 21

- ^ Valantasis, p. 455

- ^ Hoyland 1996, pp. 487–489

- ^ Louth 2002, p. 284

- ^ a b Butler, Jones & Burns 2000, p. 36

- ^ Suzanne Conklin Akbari, Idols in the East: European representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450, Cornell University Press, 2009 p. 204. David Richard Thomas, Syrian Christians under Islam: the first thousand years, Brill 2001 p. 19.

- ^ Louth 2003, p. 9

- ^ a b Catholic Online. "St. John of Damascus". catholic.org.

- ^ O'Connor, J.B. (1910), "St. John Damascene", The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company (www.newadvent.org/cathen/08459b.htm).

- ^ Cunningham, M. B. (2011). Farland, I. A.; Fergusson, D. A. S.; Kilby, K.; et al. (eds.). Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Louth 2002, pp. 17, 19

- ^ a b "John of Damascus: Johannes von Damaskus". patristik.badw.de. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Chrysostomides, Anna (2021). "John of Damascus's Theology of Icons in the Context of Eighth-Century Palestinian Iconoclasm". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 75: 263–296. ISSN 0070-7546. JSTOR 27107158.

- ^ Rhodes, Michael Craig (2011). "Handmade: A Critical Analysis of John of Damascus's Reasoning for Making Icons". The Heythrop Journal. 52 (1): 14–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2009.00549.x.

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969), pp. 109, 119; cf. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- ^ Kinnaman, Scot A. Lutheranism 101 (Concordia Publish House, St. Louis, 2010) p. 278.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts, 2006 (Church Publishing, 2006), pp. 92–93.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ Shahîd 2009, p. 195

- ^ St. John Damascene on Holy Images, Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption – Eng. transl. by Mary H. Allies, London, 1899.

- ^ a b c "Saint John of Damascus | Biography, Writings, Legacy, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis; Williams, Frank (2008). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis. Book 1 (PDF). Nag Hammadi and Manichaean studies. Vol. 63 (2nd. ed., rev. and expanded ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-4198-4.

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis; Williams, Frank (2012). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Books II and III. de Fide (PDF). Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies. Vol. 79 (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-23312-6.

- ^ a b "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Saint John Damascene". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "St. John of Damascus: Critique of Islam". orthodoxinfo.com.

- ^ Sbaihat, Ahlam (2015), "Stereotypes associated with real prototypes of the prophet of Islam's name till the 19th century". Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literature Vol. 7, No. 1, 2015, pp. 21–38. http://journals.yu.edu.jo/jjmll/Issues/vol7no12015/Nom2.pdf

- ^ Ines, Angeli Murzaku (2009). Returning home to Rome: the Basilian monks of Grottaferrata in Albania. Grottaferrata (Roma) – Italy: Analekta Kryptoferri. p. 37. ISBN 978-88-89345-04-7.

- ^ a b c d e "St. John of Damascus: Critique of Islam". orthodoxinfo.com. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Homily on the Annunciation – John of Damascus eBook: John of Damascus…". Archived from the original on 1 July 2013.

- ^ Nasrallah, Saint Jean de Damas, son époque, sa vie, son oeuvre, Harissa, 1930, p. 180

- ^ Habib Ibrahim. "Letter to Cosmas – Lettre à Cosmas de Jean Damascène (Arabe)". academia.edu.

- ^ "Philosophical chapters (Arabic) eBook: John of Damascus, Ibrahim Habi…". Archived from the original on 1 July 2013.

- ^ Nasrallah, Joseph. Histoire III, pp. 273–281

- ^ Habib Ibrahim. "Arabic life of John Damascene – Vie arabe de Jean Damascène". academia.edu.

Sources

edit- Aquilina, Mike (1999). The Fathers of the Church: An Introduction to the First Christian Teachers (illustrated ed.). Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87973-689-7.

- Michiel Op de Coul en Marcel Poorthuis, 2011. De eerste christelijke polemiek met de islam ISBN 978-90-211-4282-1

- Brown, Peter Robert Lamont (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000 (2nd, illustrated ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22138-8.

- Butler, Alban; Jones, Kathleen; Burns, Paul (2000). Butler's lives of the saints: Volume 12 of Butler's Lives of the Saints Series (Revised ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-86012-261-6.

- Griffith, Sidney (2001). "'Melkites', 'Jacobites', and the Christological Controversies in Arabic in Third/Ninth-Century Syria". In Thomas, David (ed.). Syrian Christians Under Islam: The First Thousand Years. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12055-6.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (1996). Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Darwin Press. ISBN 978-0-87850-125-0.

- Jameson (2008). Legends of the Madonna. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 978-0-554-33413-4.

- Janosik, Daniel J. (2016). John of Damascus: First Apologist to the Muslims. Eugene, Oregon: Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-4982-8984-9.

- Kontouma, Vassa (2015). John of Damascus. New Studies on his Life and Works. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-367-59921-8

- Louth, Andrew (2002). St. John Damascene: tradition and originality in Byzantine theology (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925238-1.

- Louth, Andrew (2003). Three Treatises on the Divine Images. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-245-1.

- Louth, Andrew (2005). St John Damascene: Tradition and Originality in Byzantine Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927527-4.

- McEnhill, Peter; Newlands, G. M. (2004). Fifty Key Christian Thinkers. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17049-9.

- Schadler, Peter (2017). John of Damascus and Islam: Christian Heresiology and the Intellectual Background to Earliest Christian-Muslim Relations. The History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Vol. 34. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/9789004356054. ISBN 978-90-04-34965-0. LCCN 2017044207. S2CID 165610770.

- Shahîd, Irfan (2009). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century: Economic, Social, and Cultural History, Volume 2, Part 2. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-88402-347-0.

- Sahas, Daniel J. (1972). John of Damascus on Islam. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-03495-2.

- Vila, David (2000). Richard Valantasis (ed.). Religions of Late Antiquity in Practice (Illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05751-4.

- The Works of St. John Damascene. Martis Publishing House, Moscow. 1997.

External links

edit- 131 Christians Everyone Should Know- John of Damascus

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St. John Damascene

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- Catholic Online Saints

- Details of his work

- St John Damascene on Holy Images (πρὸς τοὺς διαβάλλοντας τᾶς ἁγίας εἰκόνας). Followed by Three Sermons on the Assumption (κοίμησις) at Project Gutenberg; also available through the Internet Archive.

- Works by John of Damascus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John of Damascus at the Internet Archive

- Works by John of Damascus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "St. John of Damascus' Critique of Islam" at the Orthodox Christian Information Center

- Greek Opera Omnia by Migne, Patrologia Graeca with Analytical Indexes

- St John of Damascus Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion (4 December)

- Five Doctrinal Works is a 17th-century manuscript including three works by John of Damascus