Polynesia[a] (UK: /ˌpɒlɪˈniːziə/ POL-in-EE-zee-ə, US: /-ˈniːʒə/ -EE-zhə) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in common, including linguistic relations, cultural practices, and traditional beliefs.[1] In centuries past, they had a strong shared tradition of sailing and using stars to navigate at night.[2][3]

The term Polynésie was first used in 1756 by the French writer Charles de Brosses, who originally applied it to all the islands of the Pacific. In 1831, Jules Dumont d'Urville proposed a narrower definition during a lecture at the Société de Géographie of Paris. By tradition, the islands located in the southern Pacific have also often been called the South Sea Islands,[4] and their inhabitants have been called South Sea Islanders. The Hawaiian Islands have often been considered to be part of the South Sea Islands because of their relative proximity to the southern Pacific islands, even though they are in fact located in the North Pacific. Another term in use, which avoids this inconsistency, is "the Polynesian Triangle" (from the shape created by the layout of the islands in the Pacific Ocean). This term makes clear that the grouping includes the Hawaiian Islands, which are located at the northern vertex of the referenced "triangle".

Geography

editGeology

editPolynesia is characterized by a small amount of land spread over a very large portion of the mid- and southern Pacific Ocean. It comprises approximately 300,000 to 310,000 square kilometres (117,000 to 118,000 sq mi) of land, of which more than 270,000 km2 (103,000 sq mi) are within New Zealand. The Hawaiian archipelago comprises about half the remainder.

Most Polynesian islands and archipelagos, including the Hawaiian Islands and Samoa, are composed of volcanic islands built by hotspots (volcanoes). The other land masses in Polynesia — New Zealand, Norfolk Island, and Ouvéa, the Polynesian outlier near New Caledonia — are the unsubmerged portions of the largely sunken continent of Zealandia.[5]

Zealandia is believed to have mostly sunk below sea level 23 million years ago, and recently partially resurfaced due to a change in the movements of the Pacific Plate in relation to the Indo-Australian Plate.[6] The Pacific plate had previously been subducted under the Australian Plate. When that changed, it had the effect of uplifting the portion of the continent that is modern-day New Zealand.

The convergent plate boundary that runs northwards from New Zealand's North Island is called the Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone. This subduction zone is associated with the volcanism that gave rise to the Kermadec and Tongan islands.

There is a transform fault that currently traverses New Zealand's South Island, known as the Alpine Fault.

Zealandia's continental shelf has a total area of approximately 3,600,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi).

The oldest rocks in Polynesia are found in New Zealand and are believed to be about 510 million years old. The oldest Polynesian rocks outside Zealandia are to be found in the Hawaiian Emperor Seamount Chain and are 80 million years old.

Geographical area

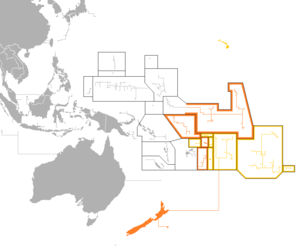

editPolynesia is generally defined as the islands within the Polynesian Triangle, although some islands inhabited by Polynesians are situated outside the Polynesian Triangle. Geographically, the Polynesian Triangle is drawn by connecting the points of Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island. The other main island groups located within the Polynesian Triangle are Samoa, Tonga, the Cook Islands, Tuvalu, Tokelau, Niue, Wallis and Futuna, and French Polynesia.

Also, small Polynesian settlements are in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, the Caroline Islands, and Vanuatu. An island group with strong Polynesian cultural traits outside of this great triangle is Rotuma, situated north of Fiji. The people of Rotuma have many common Polynesian traits, but speak a non-Polynesian language. Some of the Lau Islands to the southeast of Fiji have strong historic and cultural links with Tonga. However, in essence, Polynesia remains a cultural term referring to one of the three parts of Oceania (the others being Melanesia and Micronesia).

Island groups

editThe following islands and island groups are either nations or overseas territories of former colonial powers. The residents are native Polynesians or contain archaeological evidence indicating Polynesian settlement in the past.[b] Some islands of Polynesian origin are outside the general triangle that geographically defines the region.

Polynesian area

edit| Country / Territory | Notes |

|---|---|

| American Samoa | Unincorporated and unorganized territory of the United States; self-governing under the supervision of the Office of Insular Affairs |

| Cook Islands | State in free association with New Zealand |

| Easter Island | Province and special territory of Chile |

| French Polynesia | Overseas country of France |

| Hawaii | U.S. state |

| New Zealand | Sovereign state |

| Niue | State in free association with New Zealand |

| Norfolk Island[7] | External territory of Australia[8] |

| Pitcairn Islands | British Overseas Territory |

| Rotuma | Fijian dependency |

| Samoa | Sovereign state |

| Tokelau | Non-self-governing territory of New Zealand |

| Tonga | Sovereign state |

| Tuvalu | Sovereign state |

| Wallis and Futuna | Overseas collectivity of France |

The Line Islands and the Phoenix Islands, most of which are parts of Kiribati, had no permanent settlements until European colonization, but are often considered to be parts of the Polynesian Triangle.

Polynesians once inhabited the Auckland Islands, the Kermadec Islands, and Norfolk Island in pre-colonial times, but these islands were uninhabited by the time European explorers arrived.

The oceanic islands to the east of Easter Island, such as Clipperton Island, the Galápagos Islands, and the Juan Fernández Islands, were in the past formerly categorized on rare occasion as part of Polynesia.[9][10][11] No evidence of prehistoric contact with either Polynesians or the indigenous peoples of the Americas has been found.

Outliers

editMelanesia

edit- Anuta (in Solomon Islands)

- Bellona Island (in Solomon Islands)

- Emae (in Vanuatu)

- Fiji (excluding Rotuma and the Lau Islands)

- Mele (in Vanuatu)

- Nuguria (in Papua New Guinea)

- Nukumanu (in Papua New Guinea)

- Ontong Java (in Solomon Islands)

- Pileni (in Solomon Islands)

- Rennell (in Solomon Islands)

- Sikaiana (in Solomon Islands)

- Takuu (in Papua New Guinea)

- Tikopia (in Solomon Islands)

Micronesia

edit- Kapingamarangi (in the Federated States of Micronesia)

- Nukuoro (in the Federated States of Micronesia)

- Wake Island (a part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands)

Sub-Antarctic islands

edit- Auckland Islands (the most southerly known evidence of Polynesian settlement)[12][13][14][15]

History

editOrigins and expansion

editThe Polynesian people are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, a subset of the sea-migrating Austronesian people. Tracing Polynesian languages places their prehistoric origins in Island Melanesia, Maritime Southeast Asia, and ultimately, in Taiwan.

Between about 3000 and 1000 BC, speakers of Austronesian languages spread from Taiwan into Maritime Southeast Asia.[16][17][18]

There are three theories regarding the spread of humans across the Pacific to Polynesia. These are outlined well by Kayser et al. (2000)[19] and are as follows:

- Express Train model: A recent (c. 3000–1000 BC) expansion out of Taiwan, via the Philippines and eastern Indonesia and from the northwest ("Bird's Head") of New Guinea, on to Island Melanesia by roughly 1400 BC, reaching western Polynesian islands around 900 BC followed by a roughly 1000 year "pause" before continued settlement in central and eastern Polynesia. This theory is supported by the majority of current genetic, linguistic, and archaeological data.

- Entangled Bank model: Emphasizes the long history of Austronesian speakers' cultural and genetic interactions with indigenous Island Southeast Asians and Melanesians along the way to becoming the first Polynesians.

- Slow Boat model: Similar to the express-train model but with a longer hiatus in Melanesia along with admixture — genetically, culturally and linguistically — with the local population. This is supported by the Y-chromosome data of Kayser et al. (2000), which shows that all three haplotypes of Polynesian Y chromosomes can be traced back to Melanesia.[17]

In the archaeological record, there are well-defined traces of this expansion which allow the path it took to be followed and dated with some certainty. It is thought that by roughly 1400 BC,[20] "Lapita peoples", so-named after their pottery tradition, appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago of northwest Melanesia. This culture is seen as having adapted and evolved through time and space since its emergence "Out of Taiwan". They had given up rice production, for instance, which required paddy field agriculture unsuitable for small islands. However, they still cultivated other ancestral Austronesian staple cultigens like Dioscorea yams and taro (the latter are still grown with smaller-scale paddy field technology), as well as adopting new ones like breadfruit and sweet potato.

The results of research at the Teouma Lapita site (Efate Island, Vanuatu) and the Talasiu Lapita site (near Nuku'alofa, Tonga) published in 2016 supports the Express Train model; although with the qualification that the migration bypassed New Guinea and Island Melanesia. The conclusion from research published in 2016 is that the initial population of those two sites appears to come directly from Taiwan or the northern Philippines and did not mix with the 'Australo-Papuans' of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.[21] The preliminary analysis of skulls found at the Teouma and Talasiu Lapita sites is that they lack Australian or Papuan affinities and instead have affinities to mainland Asian populations.[22]

A 2017 DNA analysis of modern Polynesians indicates that there has been intermarriage resulting in a mixed Austronesian-Papuan ancestry of the Polynesians (as with other modern Austronesians, with the exception of Taiwanese aborigines). Research at the Teouma and Talasiu Lapita sites implies that the migration and intermarriage, which resulted in the mixed Austronesian-Papuan ancestry of the Polynesians,[17] occurred after the first initial migration to Vanuatu and Tonga.[21][23]

A complete mtDNA and genome-wide SNP comparison (Pugach et al., 2021) of the remains of early settlers of the Mariana Islands and early Lapita individuals from Vanuatu and Tonga also suggest that both migrations originated directly from the same ancient Austronesian source population from the Philippines. The complete absence of "Papuan" admixture in the early samples indicates that these early voyages bypassed eastern Indonesia and the rest of New Guinea. The authors have also suggested a possibility that the early Lapita Austronesians were direct descendants of the early colonists of the Marianas (which preceded them by about 150 years), which is also supported by pottery evidence.[24]

The most eastern site for Lapita archaeological remains recovered so far is at Mulifanua on Upolu. The Mulifanua site, where 4,288 pottery shards have been found and studied, has a "true" age of c. 1000 BC based on radiocarbon dating and is the oldest site yet discovered in Polynesia.[25] This is mirrored by a 2010 study also placing the beginning of the human archaeological sequences of Polynesia in Tonga at 900 BC.[26]

Within a mere three or four centuries, between 1300 and 900 BC, the Lapita archaeological culture spread 6,000 km further to the east from the Bismarck Archipelago, until reaching as far as Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa.[27] A cultural divide began to develop between Fiji to the west, and the distinctive Polynesian language and culture emerging on Tonga and Samoa to the east. Where there was once faint evidence of uniquely shared developments in Fijian and Polynesian speech, most of this is now called "borrowing" and is thought to have occurred in those and later years more than as a result of continuing unity of their earliest dialects on those far-flung lands. Contacts were mediated especially through the Tovata confederacy of Fiji. This is where most Fijian-Polynesian linguistic interactions occurred.[28][29]

In the chronology of the exploration and first populating of Polynesia, there is a gap commonly referred to as the long pause between the first populating of Fiji (Melanesia), Western Polynesia of Tonga and Samoa among others and the settlement of the rest of the region. In general this gap is considered to have lasted roughly 1,000 years.[30] The cause of this gap in voyaging is contentious among archaeologists with a number of competing theories presented including climate shifts,[31] the need for the development of new voyaging techniques,[32] and cultural shifts.

After the long pause, dispersion of populations into central and eastern Polynesia began. Although the exact timing of when each island group was settled is debated, it is widely accepted that the island groups in the geographic center of the region (i.e. the Cook Islands, Society Islands, Marquesas Islands, etc.) were settled initially between 1000 and 1150 AD,[33][34] and ending with more far flung island groups such as Hawaii, New Zealand, and Easter Island settled between 1200 and 1300 AD.[35][36]

Tiny populations may have been involved in the initial settlement of individual islands;[26] although Professor Matisoo-Smith of the Otago study said that the founding Māori population of New Zealand must have been in the hundreds, much larger than previously thought.[37] The Polynesian population experienced a founder effect and genetic drift.[38] The Polynesian may be distinctively different both genotypically and phenotypically from the parent population from which it is derived. This is due to new population being established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population which also causes a loss of genetic variation.[39][40]

Atholl Anderson wrote that analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA, female) and Y chromosome (male) concluded that the ancestors of Polynesian women were Austronesians while those of Polynesian men were Papuans. Subsequently, it was found that 96% (or 93.8%)[17] of Polynesian mtDNA has an Asian origin, as does one-third of Polynesian Y chromosomes; the remaining two-thirds from New Guinea and nearby islands; this is consistent with matrilocal residence patterns.[17] Polynesians existed from the intermixing of few ancient Austronesian-Melanesian founders, genetically they belong almost entirely to the Haplogroup B (mtDNA), which is the marker of Austronesian expansions. The high frequencies of mtDNA Haplogroup B in the Polynesians are the result of founder effect and represents the descendants of a few Austronesian females who intermixed with Papuan males.[38][41]

A genomic analysis of modern populations in Polynesia, published in 2021,[42] provides a model of the direction and timing of Polynesian migrations from Samoa to the islands to the east. This model presents consistencies and inconsistencies with models of Polynesian migration that are based on archaeology and linguistic analysis.[43] The 2021 genomic model presents a migration pathway from Samoa to the Cook Islands (Rarotonga), then to the Society Islands (Tōtaiete mā) in the 11th century AD, the western Austral Islands (Tuha'a Pae) and the Tuāmotu Archipelago in the 12th century AD, with the migrant pathway branching to the north to the Marquesas (Te Henua 'Enana), to Raivavae in the south, and to the easternmost destination on Easter Island (Rapa Nui), which was settled in approximately 1200 AD via Mangareva.[43]

Culture

editThe Polynesians were matrilineal and matrilocal Stone Age societies upon their arrival in Tonga, Samoa and the surrounding islands, after having spent at least some time in the Bismarck Archipelago. The modern Polynesians still show human genetic results of a Melanesian culture which allowed indigenous men, but not women, to "marry in" – useful evidence for matrilocality.[16][17][44][45]

Although matrilocality and matrilineality receded at some early time, Polynesians and most other Austronesian speakers in the Pacific Islands were and are still highly "matricentric" in their traditional jurisprudence.[44] The Lapita pottery for which the general archaeological complex of the earliest "Oceanic" Austronesian speakers in the Pacific Islands are named also lapsed in Western Polynesia. Language, social life and material culture were very distinctly "Polynesian" by 1000 BC.

Early European observers detected theocratic elements in traditional Polynesian government.[46]

Linguistically, there are five sub-groups of the Polynesian language group. Each represents a region within Polynesia and the categorization of these language groups by Green in 1966 helped to confirm that Polynesian settlement generally took place from west to east. There is a very distinct "East Polynesian" subgroup with many shared innovations not seen in other Polynesian languages. The Marquesas dialects are perhaps the source of the oldest Hawaiian speech which is overlaid by Tahitian-variety speech, as Hawaiian oral histories would suggest. The earliest varieties of New Zealand Māori speech may have had multiple sources from around central Eastern Polynesia, as Māori oral histories would suggest.[47]

Political history

editCook Islands

editThe Cook Islands are made up of 15 islands comprising the Northern and Southern groups. The islands are spread out across many kilometers of a vast ocean. The largest of these islands is called Rarotonga, which is also the political and economic capital of the nation.

The Cook Islands were formerly known as the Hervey Islands, but this name refers only to the Northern Groups. It is unknown when this name was changed to reflect the current name. It is thought that the Cook Islands were settled in two periods: the Tahitian Period, when the country was settled between 900 and 1300 AD, and the Maui Settlement, which occurred in 1600 AD, when a large contingent from Tahiti settled in Rarotonga, in the Takitumu district.

The first contact between Europeans and the native inhabitants of the Cook Islands took place in 1595 with the arrival of Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña in Pukapuka, who called it San Bernardo (Saint Bernard). A decade later, navigator Pedro Fernández de Quirós made the first European landing in the islands when he set foot on Rakahanga in 1606, calling it Gente Hermosa (Beautiful People).[48][49]

Cook Islanders are ethnically Polynesians or Eastern Polynesia. They are culturally associated with Tahiti, Eastern Islands, New Zealand Māori and Hawaii.

Fiji

editThe Lau Islands were subject to periods of Tongan rulership and then Fijian control until their eventual conquest by Seru Epenisa Cakobau of the Kingdom of Fiji by 1871. In around 1855 a Tongan prince, Enele Ma'afu, proclaimed the Lau islands as his kingdom, and took the title Tui Lau.

Fiji had been ruled by numerous divided chieftains until Cakobau unified the landmass. The Lapita culture, the ancestors of the Polynesians, existed in Fiji from about 3500 BC until they were displaced by the Melanesians about a thousand years later. (Both Samoans and subsequent Polynesian cultures adopted Melanesian painting and tattoo methods.)

In 1873, Cakobau ceded a Fiji heavily indebted to foreign creditors to the United Kingdom. It became independent on 10 October 1970 and a republic on 28 September 1987.

Fiji is classified as Melanesian and (less commonly) Polynesian.

Hawaii

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

-

On February 14, 1779, Capt. James Cook was killed on the island of Hawaii.

-

A depiction of a royal heiau (Hawaiian temple) at Kealakekua Bay, c. 1816

-

King Kamehameha I receiving the Russian naval expedition of Otto von Kotzebue. Drawing by Louis Choris in 1816.

Kiribati

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2024) |

Marquesas Islands

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

New Zealand

editBeginning in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Polynesians began to migrate in waves to New Zealand via their canoes, settling on both the North and South islands as well as the Chatham Islands. Over the course of several centuries, the Polynesian settlers formed distinct cultures that became known as the Māori on the New Zealand mainland, while those who settled in the Chatham Islands became the Moriori people.[51] Beginning the 17th century, the arrival of Europeans to New Zealand drastically impacted Māori culture. Settlers from Europe (known as "Pākehā") began to colonize New Zealand in the 19th century, leading to tension with the indigenous Māori.[52] On October 28, 1835, a group of Māori tribesmen issued a declaration of independence (drafted by Scottish businessman James Busby) as the "United Tribes of New Zealand", in order to resist potential efforts at colonizing New Zealand by the French and prevent merchant ships and their cargo which belonged to Māori merchants from being seized at foreign ports. The new state received recognition from the British Crown in 1836.[53]

In 1840, Royal Navy officer William Hobson and several Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi, which transformed New Zealand into a colony of the British Empire and granting all Māori the status of British subjects.[54] However, tensions between Pākehā settlers and the Māori over settler encroachment on Māori lands and disputes over land sales led to the New Zealand Wars (1845–1872) between the colonial government and the Māori. In response to the conflict, the colonial government initiated a series of land confiscations from the Māori.[55] This social upheaval, combined with epidemics of infectious diseases from Europe, devastated both the Māori population and their social standing in New Zealand. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the Maori population began to recover, and efforts were made to redress social, economic, political and economic issues facing the Māori in wider New Zealand society. Beginning in the 1960s, a protest movement emerged seeking redress for historical grievances.[56] In the 2013 New Zealand census, roughly 600,000 people in New Zealand identified as being Māori.

Niue

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Samoa

editIn the 9th century, the Tui Manuʻa controlled a vast maritime empire comprising most of the settled islands of Polynesia. The Tui Manuʻa is one of the oldest Samoan titles in Samoa. Traditional oral literature of Samoa and Manu'a talks of a widespread Polynesian network or confederacy (or "empire") that was prehistorically ruled by the successive Tui Manuʻa dynasties. Manuan genealogies and religious oral literature also suggest that the Tui Manuʻa had long been one of the most prestigious and powerful paramount of Samoa. Oral history suggests that the Tui Manuʻa kings governed a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji, Tonga as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdoms and Polynesian outliers such as Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies are well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manuʻa dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory "tabua", obsidian and basalt tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus and the egg cowry).

Samoa's long history of various ruling families continued until well after the decline of the Tui Manuʻa's power, with the western isles of Savaiʻi and Upolu rising to prominence in the post-Tongan occupation period and the establishment of the tafaʻifa system that dominated Samoan politics well into the 20th century. This was disrupted in the early 1900s due to colonial intervention, with east–west division by Tripartite Convention (1899) and subsequent annexation by the German Empire and the United States. The German-controlled Western portion of Samoa (consisting of the bulk of Samoan territory – Savaiʻi, Apolima, Manono and Upolu) was occupied by New Zealand in WWI, and administered by it under a Class C League of Nations mandate. After repeated efforts by the Samoan independence movement, the New Zealand Western Samoa Act of 24 November 1961 granted Samoa independence, effective on January 1, 1962, upon which the Trusteeship Agreement terminated. The new Independent State of Samoa was not a monarchy, though the Malietoa titleholder remained very influential. It effectively ended however with the death of Malietoa Tanumafili II, the country's head of state, on May 11, 2007.

Tahiti

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Tonga

editIn the 10th century, the Tuʻi Tonga Empire was established in Tonga, and most of the Western Pacific came within its sphere of influence, up to parts of the Solomon Islands. The Tongan influence brought Polynesian customs and language throughout most of Polynesia. The empire began to decline in the 13th century.

After a bloody civil war, political power in Tonga eventually fell under the Tuʻi Kanokupolu dynasty in the 16th century.

In 1845, the ambitious young warrior, strategist, and orator Tāufaʻāhau united Tonga into a more Western-style kingdom. He held the chiefly title of Tuʻi Kanokupolu, but had been baptised with the name Jiaoji ("George") in 1831. In 1875, with the help of the missionary Shirley Waldemar Baker, he declared Tonga a constitutional monarchy, formally adopted the western royal style, emancipated the "serfs", enshrined a code of law, land tenure, and freedom of the press, and limited the power of the chiefs.

Tonga became a British protectorate under a Treaty of Friendship on 18 May 1900, when European settlers and rival Tongan chiefs tried to oust the second king. Within the British Empire, which posted no higher permanent representative on Tonga than a British Consul (1901–1970), Tonga formed part of the British Western Pacific Territories (under a High Commissioner who residing in Fiji) from 1901 until 1952. Despite being under the protectorate, Tonga retained its monarchy without interruption. On June 4, 1970, the Kingdom of Tonga became independent from the British Empire.[57]

Tuvalu

editThe reef islands and atolls of Tuvalu are identified as being part of West Polynesia. During pre-European-contact times there was frequent canoe voyaging between the islands as Polynesian navigation skills are recognised to have allowed deliberate journeys on double-hull sailing canoes or outrigger canoes.[58] Eight of the nine islands of Tuvalu were inhabited; thus the name, Tuvalu, means "eight standing together" in Tuvaluan. The pattern of settlement that is believed to have occurred is that the Polynesians spread out from Samoa and Tonga into the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone for migration into the Polynesian outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.[59][60][61]

Stories as to the ancestors of the Tuvaluans vary from island to island. On Niutao,[62] Funafuti and Vaitupu the founding ancestor is described as being from Samoa;[63][64] whereas on Nanumea the founding ancestor is described as being from Tonga.[63]

The extent of influence of the Tuʻi Tonga line of Tongan kings, which originated in the 10th century, is understood to have extended to some of the islands of Tuvalu in the 11th to mid-13th century.[64] The oral history of Niutao recalls that in the 15th century Tongan warriors were defeated in a battle on the reef of Niutao. Tongan warriors also invaded Niutao later in the 15th century and again were repelled. A third and fourth Tongan invasion of Niutao occurred in the late 16th century, again with the Tongans being defeated.[62]

Tuvalu was first sighted by Europeans in January 1568 during the voyage of Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira who sailed past the island of Nui, and charted it as Isla de Jesús (Spanish for "Island of Jesus") because the previous day was the feast of the Holy Name. Mendaña made contact with the islanders but did not land.[65] During Mendaña's second voyage across the Pacific he passed Niulakita in August 1595, which he named La Solitaria, meaning "the solitary one".[65][66]

Fishing was the primary source of protein, with the Tuvaluan cuisine reflecting food that could be grown on low-lying atolls. Navigation between the islands of Tuvalu was carried out using outrigger canoes. The population levels of the low-lying islands of Tuvalu had to be managed because of the effects of periodic droughts and the risk of severe famine if the gardens were poisoned by salt from the storm surge of a tropical cyclone.

Links to the Americas

editThe sweet potato, called kūmara in Māori and kumar in Quechua, is native to the Americas and was widespread in Polynesia when Europeans first reached the Pacific. Remains of the plant in the Cook Islands have been radiocarbon-dated to 1000, and the present scholarly consensus[67] is that it was brought to central Polynesia c. 700 by Polynesians who had traveled to South America and back, from where it spread across the region.[68] Some genetic evidence suggests that sweet potatoes may have reached Polynesia via seeds at least 100,000 years ago, pre-dating human arrival;[69] however, this hypothesis fails to account for the similarity of names.

There are also other possible material and cultural evidence of Pre-Columbian contact by Polynesia with the Americas with varying levels of plausibility. These include chickens, coconuts, and bottle gourds. The question of whether Polynesians reached the Americas and the extent of cultural and material influences resulting from such a contact remains highly contentious among anthropologists.[70]

One of the most enduring misconceptions about Polynesians was that they originated from the Americas. This was due to Thor Heyerdahl's proposals in the mid-20th century that the Polynesians had migrated in two waves of migrations: one by Native Americans from the northwest coast of Canada by large whale-hunting dugouts; and the other from South America by "bearded white men" with "reddish to blond hair" and "blue-grey eyes" led by a high priest and sun-king named "Kon-Tiki" on balsa-log rafts. He claimed the "white men" then "civilized" the dark-skinned natives in Polynesia. He set out to prove this by embarking on a highly publicized Kon-Tiki expedition on a primitive raft with a Scandinavian crew. It captured the public's attention, making the Kon-Tiki a household name.[71][72][73]

None of Heyerdahl's proposals have been accepted in the scientific community.[74][75][76] The anthropologist Wade Davis in his book The Wayfinders, criticized Heyerdahl as having "ignored the overwhelming body of linguistic, ethnographic, and ethnobotanical evidence, augmented today by genetic and archaeological data, indicating that he was patently wrong."[77] Anthropologist Robert Carl Suggs included a chapter titled "The Kon-Tiki Myth" in his 1960 book on Polynesia, concluding that "The Kon-Tiki theory is about as plausible as the tales of Atlantis, Mu, and 'Children of the Sun'. Like most such theories, it makes exciting light reading, but as an example of scientific method it fares quite poorly."[78] Other authors have also criticized Heyerdahl's hypothesis for its implicit racism in attributing advances in Polynesian society to "white people", at the same time ignoring relatively advanced Austronesian maritime technology in favor of a primitive balsa raft.[73][79][80]

In July 2020, a novel high-density genome-wide DNA analysis of Polynesians and Native South Americans reported that there has been intermingling between Polynesian people and pre-Columbian Zenú people in a period dated between 1150 and 1380 AD.[81] Whether this happened because of indigenous American people reaching eastern Polynesia or because the northern coast of South America was visited by Polynesians is not clear yet.[82]

Cultures

editPolynesia divides into two distinct cultural groups, East Polynesia and West Polynesia. The culture of West Polynesia is conditioned to high populations. It has strong institutions of marriage and well-developed judicial, monetary and trading traditions. West Polynesia comprises the groups of Tonga, Samoa and surrounding islands. The pattern of settlement to East Polynesia began from Samoan Islands into the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone to migration into the Polynesian outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.[59][60][61]

Eastern Polynesian cultures are highly adapted to smaller islands and atolls, principally Niue, the Cook Islands, Tahiti, the Tuamotus, the Marquesas, Hawaii, Rapa Nui, and smaller central-pacific groups. The large islands of New Zealand were first settled by Eastern Polynesians who adapted their culture to a non-tropical environment.

Unlike western Melanesia, leaders were chosen in Polynesia based on their hereditary bloodline. Samoa, however, had another system of government that combines elements of heredity and real-world skills to choose leaders. This system is called Fa'amatai. According to Ben R. Finney and Eric M. Jones, "On Tahiti, for example, the 35,000 Polynesians living there at the time of European discovery were divided between high-status persons with full access to food and other resources, and low-status persons with limited access."[83]

Religion, farming, fishing, weather prediction, out-rigger canoe (similar to modern catamarans) construction and navigation were highly developed skills because the population of an entire island depended on them. Trading of both luxuries and mundane items was important to all groups. Periodic droughts and subsequent famines often led to war.[83] Many low-lying islands could suffer severe famine if their gardens were poisoned by the salt from the storm surge of a tropical cyclone. In these cases fishing, the primary source of protein, would not ease the loss of food energy. Navigators, in particular, were highly respected and each island maintained a house of navigation with a canoe-building area.

Settlements by the Polynesians were of two categories: the hamlet and the village. The size of the island inhabited determined whether or not a hamlet would be built. The larger volcanic islands usually had hamlets because of the many zones that could be divided across the island. Food and resources were more plentiful. These settlements of four to five houses (usually with gardens) were established so that there would be no overlap between the zones. Villages, on the other hand, were built on the coasts of smaller islands and consisted of thirty or more houses—in the case of atolls, on only one of the group so that food cultivation was on the others. Usually, these villages were fortified with walls and palisades made of stone and wood.[84]

However, New Zealand demonstrates the opposite: large volcanic islands with fortified villages.

As well as being great navigators, these people were artists and artisans of great skill. Simple objects, such as fish-hooks would be manufactured to exacting standards for different catches and decorated even when the decoration was not part of the function. Stone and wooden weapons were considered to be more powerful the better they were made and decorated. In some island groups weaving was a strong part of the culture and gifting woven articles was an ingrained practice. Dwellings were imbued with character by the skill of their building. Body decoration and jewelry is of an international standard to this day.

The religious attributes of Polynesians were common over the whole Pacific region. While there are some differences in their spoken languages they largely have the same explanation for the creation of the earth and sky, for the gods that rule aspects of life and for the religious practices of everyday life. People traveled thousands of miles to celebrations that they all owned communally.

Beginning in the 1820s large numbers of missionaries worked in the islands, converting many groups to Christianity. Polynesia, argues Ian Breward, is now "one of the most strongly Christian regions in the world....Christianity was rapidly and successfully incorporated into Polynesian culture. War and slavery disappeared."[85]

Languages

editPolynesian languages are all members of the family of Oceanic languages, a sub-branch of the Austronesian language family. Polynesian languages show a considerable degree of similarity. The vowels are generally the same—/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/, pronounced as in Italian, Spanish, and German—and the consonants are always followed by a vowel. The languages of various island groups show changes in consonants. The glottal stop /ʔ/ is increasingly represented by an inverted comma or ʻokina. In the Society Islands, the original Proto-Polynesian *k and *ŋ (or the ng sound) have merged as /ʔ/, *s changed to /h/, and *w changed to /v/; so the name for the ancestral homeland, deriving from Proto-Nuclear Polynesian *sawaiki,[86] becomes Havaiʻi. In New Zealand, where *s changed to /h/, the ancient home is Hawaiki. In the Cook Islands, where /ʔ/ replaces *s (with a likely intermediate stage of *h) and /v/ replaces *w, it is ʻAvaiki. In the Hawaiian islands, where /ʔ/ and /h/ replace *k and *s, respectively, the largest island of the group is named Hawaiʻi. In Samoa, where /v/ and /ʔ/ replace *w and *k, respectively, the largest island is called Savaiʻi.[1]

Economy

editWith the exception of New Zealand, the majority of independent Polynesian islands derive much of their income from foreign aid and remittances from those who live in other countries. Some encourage their young people to go where they can earn good money to remit to their stay-at-home relatives. Many Polynesian locations, such as Easter Island, supplement this with tourism income. Some have more unusual sources of income, such as Tuvalu which marketed its '.tv' internet top-level domain name or the Cooks that relied on postage stamp sales.

Aside from New Zealand, another focus area of economic dependence regarding tourism is Hawaii. Hawaii is one of the most visited areas within the Polynesian Triangle, entertaining more than ten million visitors annually, excluding 2020. The economy of Hawaii, like that of New Zealand, is steadily dependent on annual tourists and financial counseling or aid from other countries or states. "The rate of tourist growth has made the economy overly dependent on this one sector, leaving Hawaii extremely vulnerable to external economic forces."[87] By keeping this in mind, island states and nations similar to Hawaii are paying closer attention to other avenues that can positively affect their economy by practicing more independence and less emphasis on tourist entertainment.

Inter-Polynesian cooperation

editThe first major attempt at uniting the Polynesian islands was by Imperial Japan in the 1930s, when various theorists (chiefly Hachirō Arita) began promulgating the idea of what would soon become known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Under the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, all nations stretching from Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia to Oceania would be united under one, large, cultural and economic bloc which would be free from Western imperialism. The policy theorists who conceived it, along with the Japanese public, largely saw it as a pan-Asian movement driven by ideals of freedom and independence from Western colonial oppression. In practice, however, it was frequently corrupted by militarists who saw it as an effective policy vehicle through which to strengthen Japan's position and advance its dominance within Asia. At its greatest extent, it stretched from Japanese occupied Indochina in the west to the Gilbert Islands in the east, although it was originally planned to stretch as far east as Hawaii and Easter Island and as far west as India. This never came to fruition, however, as Japan was defeated during World War II and subsequently lost all power and influence it had.[88][89]

After several years of discussing a potential regional grouping, three sovereign states (Samoa, Tonga, and Tuvalu) and five self-governing but non-sovereign territories formally launched, in November 2011, the Polynesian Leaders Group, intended to cooperate on a variety of issues including culture and language, education, responses to climate change, and trade and investment. It does not, however, constitute a political or monetary union.[90][91][92]

Navigation

editPolynesia comprised islands diffused throughout a triangular area with sides of four thousand miles. The area from the Hawaiian Islands in the north, to Easter Island in the east and to New Zealand in the south were all settled by Polynesians.

Navigators traveled to small inhabited islands using only their own senses and knowledge passed by oral tradition from navigator to apprentice. In order to locate directions at various times of day and year, navigators in Eastern Polynesia memorized important facts: the motion of specific stars, and where they would rise on the horizon of the ocean; weather; times of travel; wildlife species (which congregate at particular positions); directions of swells on the ocean, and how the crew would feel their motion; colors of the sea and sky, especially how clouds would cluster at the locations of some islands; and angles for approaching harbors.

These wayfinding techniques, along with outrigger canoe construction methods, were kept as guild secrets. Generally, each island maintained a guild of navigators who had very high status; in times of famine or difficulty these navigators could trade for aid or evacuate people to neighboring islands. On his first voyage of Pacific exploration Cook had the services of a Polynesian navigator, Tupaia, who drew a hand-drawn chart of the islands within 3,200 km (2,000 mi) radius (to the north and west) of his home island of Ra'iatea. Tupaia had knowledge of 130 islands and named 74 on his chart.[93] Tupaia had navigated from Ra'iatea in short voyages to 13 islands. He had not visited western Polynesia, as since his grandfather's time the extent of voyaging by Raiateans has diminished to the islands of eastern Polynesia. His grandfather and father had passed to Tupaia the knowledge as to the location of the major islands of western Polynesia and the navigation information necessary to voyage to Samoa, Tonga and Melanesian island of Fiji.[94] As the Admiralty orders directed Cook to search for the "Great Southern Continent", Cook ignored Tupaia's chart and his skills as a navigator. To this day, original traditional methods of Polynesian Navigation are still taught in the Polynesian outlier of Taumako Island in the Solomon Islands.

From a single chicken bone recovered from the archaeological site of El Arenal-1, on the Arauco Peninsula, Chile, a 2007 research report looking at radiocarbon dating and an ancient DNA sequence indicate that Polynesian navigators may have reached the Americas at least 100 years before Columbus (who arrived 1492 AD), introducing chickens to South America.[95][96] A later report looking at the same specimens concluded:

A published, apparently pre-Columbian, Chilean specimen and six pre-European Polynesian specimens also cluster with the same European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America. In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal. Modeling of the potential marine carbon contribution to the Chilean archaeological specimen casts further doubt on claims for pre-Columbian chickens, and definitive proof will require further analyses of ancient DNA sequences and radiocarbon and stable isotope data from archaeological excavations within both Chile and Polynesia.[97]

Knowledge of the traditional Polynesian methods of navigation was largely lost after contact with and colonization by Europeans. This left the problem of accounting for the presence of the Polynesians in such isolated and scattered parts of the Pacific. By the late 19th century to the early 20th century, a more generous view of Polynesian navigation had come into favor, perhaps creating a romantic picture of their canoes, seamanship and navigational expertise.

In the mid to late 1960s, scholars began testing sailing and paddling experiments related to Polynesian navigation: David Lewis sailed his catamaran from Tahiti to New Zealand using stellar navigation without instruments and Ben Finney built a 12-meter (40-foot) replica of a Hawaiian double canoe "Nalehia" and tested it in Hawaii.[98] Meanwhile, Micronesian ethnographic research in the Caroline Islands revealed that traditional stellar navigational methods were still in everyday use. Recent re-creations of Polynesian voyaging have used methods based largely on Micronesian methods and the teachings of a Micronesian navigator, Mau Piailug.

It is probable that the Polynesian navigators employed a whole range of techniques including use of the stars, the movement of ocean currents and wave patterns, the air and sea interference patterns caused by islands and atolls, the flight of birds, the winds and the weather. Scientists think that long-distance Polynesian voyaging followed the seasonal paths of birds. There are some references in their oral traditions to the flight of birds and some say that there were range marks onshore pointing to distant islands in line with these flyways. One theory is that they would have taken a frigatebird with them. These birds refuse to land on the water as their feathers will become waterlogged making it impossible to fly. When the voyagers thought they were close to land they may have released the bird, which would either fly towards land or else return to the canoe. It is likely that the Polynesians also used wave and swell formations to navigate. It is thought that the Polynesian navigators may have measured the time it took to sail between islands in "canoe-days" or a similar type of expression.

Another navigational technique may have involved following sea turtle migrations. While other navigational techniques may have been sufficient to reach known islands, some research finds only sea turtles could have helped Polynesian navigators reach new islands. Sea turtle migrations are feasible for canoes to follow, at shallow depths, slower speeds, and in large groups. This could explain how Polynesians were able to find and settle the majority of Pacific Islands.[99]

Also, people of the Marshall Islands used special devices called stick charts, showing the places and directions of swells and wave-breaks, with tiny seashells affixed to them to mark the positions of islands along the way. Materials for these maps were readily available on beaches, and their making was simple; however, their effective use needed years and years of study.[100]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Tongan: Polinisia; Māori: Poronihia; Hawaiian: Polenekia; Fijian: Polinisia; Samoan: Polenisia; Cook Islands Māori: Porinetia; Tahitian: Pōrīnetia; Tuvaluan: Polenisia; Tokelauan: Polenihia; French: Polynésie; Spanish: Polinesia. From Ancient Greek: πολύς (polýs) "many" and νῆσος (nêsos) "island".

- ^ Islands that were uninhabited at contact but which have archaeological evidence of Polynesian settlement include Norfolk Island, Pitcairn, New Zealand's Kermadec Islands and some small islands near Hawaii.

References

edit- ^ a b Hiroa, Te Rangi (Sir Peter Henry Buck) (1964). Vikings of the Sunrise (reprint ed.). Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd. p. 67. Retrieved 2 March 2010 – via NZ Electronic Text Centre, Victoria University, NZ Licence CC BY-SA 3.0.

- ^ Holmes, Lowell Don (1 June 1955). "Island Migrations (1): The Polynesian Navigators Followed a Unique Plan". XXV(11) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Lowell Don (1 August 1955). "Island Migrations (2): Birds and Sea Currents Aided Canoe Navigators". XXVI(1) Pacific Islands Monthly. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Russell, Michael (1849). Polynesia: A History of the South Sea Islands, including New Zealand.

- ^ Mortimer, Nick; Campbell, Hamish J. (2017). "Zealandia: Earth's Hidden Continent". GSA Today. 27: 27–35. doi:10.1130/GSATG321A.1. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- ^ "The sinking of Moa's Ark". New Zealand Herald. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl; White, Peter (2001). "Prehistoric Settlement on Norfolk Island and its Oceanic Context" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 27 (Supplement 27): 135–141. doi:10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1348. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Governance & Administration". Attorney-General's Department. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010.

- ^ Stanley, David (1979). South Pacific Handbook. Moon Publications. p. 43. ISBN 9780918373298. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Moncrieff, Robert Hope (1907). The World of To-day A Survey of the Lands and Peoples of the Globe as Seen in Travel and Commerce: Volume 4. Oxford University. p. 222. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Udvardy, Miklos D.F. "A Classification of the Biogeographical Provinces of the World" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Tom (2004). "Polynesians in the Southern Ocean: Occupation of the Auckland Islands in Prehistory". New Zealand Geographic. 69: 6–8.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl and O'Regan, Gerard R. (2000) "To the Final Shore: Prehistoric Colonisation of the Subantarctic Islands in South Polynesia", pp. 440–454 in Australian Archaeologist: Collected Papers in Honour of Jim Allen Canberra: Australian National University.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl and O'Regan, Gerard R. (1999) "The Polynesian Archaeology of the Subantarctic Islands: An Initial Report on Enderby Island". Southern Margins Project Report. Dunedin: Ngai Tahu Development Report

- ^ Anderson, Atholl (2005). "Subpolar Settlement in South Polynesia". Antiquity. 79 (306): 791–800. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00114930. S2CID 162770473.

- ^ a b Hage, P.; Marck, J. (2003). "Matrilineality and Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y Chromosomes". Current Anthropology. 44 (S5): S121. doi:10.1086/379272. S2CID 224791767.

- ^ a b c d e f Kayser, Manfred; Brauer, Silke; Cordaux, Richard; Casto, Amanda; Lao, Oscar; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Moyse-Faurie, Claire; Rutledge, Robb B.; Schiefenhoevel, Wulf; Gil, David; Lin, Alice A.; Underhill, Peter A.; Oefner, Peter J.; Trent, Ronald J.; Stoneking, Mark (2006). "Melanesian and Asian Origins of Polynesians: MtDNA and y Chromosome Gradients Across the Pacific" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. pp. 2234–2244. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl093. PMID 16923821. Archived from the original (PDF) on Mar 3, 2022.

- ^ Su, B.; Jin, L.; Underhill, P.; Martinson, J.; Saha, N.; McGarvey, S. T.; Shriver, M. D.; Chu, J.; Oefner, P.; Chakraborty, R.; Deka, R. (2000). "Polynesian origins: Insights from the Y chromosome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (15): 8225–8228. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.8225S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.15.8225. PMC 26928. PMID 10899994.

- ^ Kayser, M.; Brauer, S.; Weiss, G.; Underhill, P.; Roewer, L.; Schiefenhövel, W.; Stoneking, M. (2000). "Melanesian origin of Polynesian Y chromosomes". Current Biology. 10 (20): 1237–46. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1237K. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00734-X. PMID 11069104. S2CID 744958.

- ^ Kirch, P. V. (2000). On the road of the wings: an archaeological history of the Pacific Islands before European contact. London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520234611. Quoted in Kayser, M.; et al. (2006).

- ^ a b Pontus Skoglund; et al. (27 October 2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418.

- ^ Skoglund, Pontus; Posth, Cosimo; Sirak, Kendra; Spriggs, Matthew; Valentin, Frederique; Bedford, Stuart; Clark, Geoffrey R.; Reepmeyer, Christian; Petchey, Fiona; Fernandes, Daniel; Fu, Qiaomei; Harney, Eadaoin; Lipson, Mark; Mallick, Swapan; Novak, Mario; Rohland, Nadin; Stewardson, Kristin; Abdullah, Syafiq; Cox, Murray P.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Friedlaender, Jonathan S.; Kivisild, Toomas; Koki, George; Kusuma, Pradiptajati; Merriwether, D. Andrew; Ricaut, Francois-X.; Wee, Joseph T. S.; Patterson, Nick; Krause, Johannes; Pinhasi, Ron (3 October 2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific – Supplementary Note 1: The Teouma site / Supplementary Note 2: The Talasiu site". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418.

- ^ "First ancestry of Ni-Vanuatu is Asian: New DNA Discoveries recently published". Island Business. December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ Pugach, Irina; Hübner, Alexander; Hung, Hsiao-chun; Meyer, Matthias; Carson, Mike T.; Stoneking, Mark (2021). "Ancient DNA from Guam and the Peopling of the Pacific". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (1). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11822112P. doi:10.1073/pnas.2022112118. PMC 7817125. PMID 33443177.

- ^ Green, Roger C.; Leach, Helen M. (1989). "New Information for the Ferry Berth Site, Mulifanua, Western Samoa". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 98 (3): 319–329. JSTOR 20706295. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ a b Burley, David V.; Barton, Andrew; Dickinson, William R.; Connaughton, Sean P.; Taché, Karine (2010). "Nukuleka as a Founder Colony for West Polynesian Settlement: New Insights from Recent Excavations". Journal of Pacific Archaeology. 1 (2): 128–144. doi:10.70460/jpa.v1i2.26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ignored DOI errors (link) - ^ Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-0500274507.

- ^ Pawley, Andrew (2007). "Why do Polynesian island groups have one language and Melanesian island groups have many? Patterns of interaction and diversification in the Austronesian colonization of Remote Oceania" (PDF). p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-09. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ Clark, Geoffrey; Anderson, Atholl. "Colonisation and culture change in the early prehistory of Fiji" (PDF). Terra Australis. pp. 417–418. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ Finney, Ben (1977). "Voyaging Canoes and the Settlement of Polynesia". Science. 196 (4296): 1277–1285. Bibcode:1977Sci...196.1277F. doi:10.1126/science.196.4296.1277. JSTOR 1744728. PMID 17831736. S2CID 2836072.

- ^ Finney, Ben R. (1985). "Anomalous Westerlies, El Niño, and the Colonization of Polynesia". American Anthropologist. 87 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1525/aa.1985.87.1.02a00030. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 677659.

- ^ Di Piazza, Anne; Di Piazza, Philippe; Pearthree, Erik (2007-08-01). "Sailing virtual canoes across Oceania: revisiting island accessibility". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (8): 1219–1225. Bibcode:2007JArSc..34.1219D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.013. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (5): 1815–20. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1815W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. PMC 3033267. PMID 21187404.

- ^ Irwin, Geoffry (1990). "Voyaging by Canoe and Computer: experiments in the settlement of the Pacific Ocean". Antiquity. 64 (242): 34–50. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00077280. S2CID 164203366.

- ^ Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P. (2006). "Late Colonization of Easter Island". Science. 311 (5767): 1603–1606. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1603H. doi:10.1126/science.1121879. PMID 16527931. S2CID 41685107.

- ^ Hunt, Terry; Lipo, Carl (2011). The Statues that Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-5031-3.

- ^ "Who were the first humans to reach New Zealand (with map)". Stuff (Fairfax). 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b Murray-McIntosh, Rosalind P.; Scrimshaw, Brian J.; Hatfield, Peter J.; Penny, David (21 July 1998). "Testing migration patterns and estimating founding population size in Polynesia by using human mtDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (15): 9047–9052. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9047M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9047. PMC 21200. PMID 9671802.

- ^ Provine, W. B. (2004). "Ernst Mayr: Genetics and speciation". Genetics. 167 (3): 1041–6. doi:10.1093/genetics/167.3.1041. PMC 1470966. PMID 15280221.

- ^ Templeton, A. R. (1980). "The theory of speciation via the founder principle". Genetics. 94 (4): 1011–38. doi:10.1093/genetics/94.4.1011. PMC 1214177. PMID 6777243.

- ^ Assessing Y-chromosome Variation in the South Pacific Using Newly Detected, By Krista Erin Latham [1] Archived 2015-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ioannidis, A.G.; Blanco-Portillo, J.; Sandoval, K.; et al. (2021). "Paths and timings of the peopling of Polynesia inferred from genomic networks". Nature. 597 (7877): 522–526. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..522I. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03902-8. PMC 9710236. PMID 34552258. S2CID 237608692.

- ^ a b Kirch, Patrick V. (2021). "Modern Polynesian genomes offer clues to early eastward migrations". Nature. 597 (7877): 477–478. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..477K. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01719-z. PMID 34552247. S2CID 237606683.

- ^ a b Hage, P. (1998). "Was Proto Oceanic Society matrilineal?". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 107 (4): 365–379. JSTOR 20706828.

- ^ Marck, J. (2008). "Proto Oceanic Society was matrilineal". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 117 (4): 345–382. JSTOR 20707458.

- ^

For example:

Moerenhout, Jacques Antoine (1993) [1837]. Travels to the Islands of the Pacific Ocean. Translated by Borden, Arthur R. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. p. 295. ISBN 9780819188984. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

It was not rare, either, to see the priestly functions and the administrative united under one head in such a way as to give a government the character of a true theocracy, which always happened when a dead chief was replaced by a brother or near relative already invested with the priestly functions [...] the grand priest was almost always a brother or near relative of his chief [...].

- ^ Green, Roger (1966). "Linguistic Subgrouping within Polynesia: The Implications for Prehistoric Settlement". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 75 (1): 6–38. ISSN 0032-4000. JSTOR 20704347.

- ^ "Rakahanga – Island of Beautiful People". www.ck.

- ^ "History of Rarotonga & the Cook Islands: European explorers". Lonely Planet.

- ^ Hawkesworth J, Wallis JS, Byron J, Carteret P, Cook J, Banks J (1773) An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, vol 1, chap 10. W. Strahan and T. Cadell in the Strand.

- ^ Roberton, J.B.W. (1956). "Genealogies as a basis for Maori chronology". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 65 (1): 45–54. Archived from the original on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ^ Thompson, Christina A. (June 1997). "A dangerous people whose only occupation is war: Maori and Pakeha in 19th century New Zealand". Journal of Pacific History. 32 (1): 109–119. doi:10.1080/00223349708572831.

- ^ "Taming the frontier Page 4 – Declaration of Independence". NZ History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Orange, Claudia (20 June 2012). "Treaty of Waitangi – Creating the Treaty of Waitangi". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand, Penguin, 2000, page 146 ISBN 0-14-029875-4

- ^ Walker, R. J. (1984). "The Genesis of Maori Activism". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 93 (3): 267–281. ISSN 0032-4000. JSTOR 20705873.

- ^ "Tonga's 150 Polynesian Islands Now Independent". The New York Times. 5 June 1970. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 39–44.

- ^ a b Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 29, 54. ISBN 978-0500274507.

- ^ a b Bayard, D.T. (1976). The Cultural Relationships of the Polynesian Outiers. Otago University, Studies in Prehistoric Anthropology, Vol. 9.

- ^ a b Kirch, P.V. (1984). "The Polynesian Outiers". Journal of Pacific History. 95 (4): 224–238. doi:10.1080/00223348408572496.

- ^ a b Sogivalu, Pulekau A. (1992). A Brief History of Niutao. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. ISBN 978-982-02-0058-6.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Talakatoa (1983). Tuvalu: A History, Chapter 1, Genesis. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Government of Tuvalu.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Donald G. (1929). "Field Notes on the Culture of Vaitupu, Ellice Islands". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 38: 2–5. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ a b Maude, H. E. (1959). "Spanish Discoveries in the Central Pacific: A Study in Identification". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 68 (4): 284–326. Archived from the original on 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Chambers, Keith S.; Munro, Doug (1980). The Mystery of Gran Cocal: European Discovery and Mis-Discovery in Tuvalu. 89(2) The Journal of the Polynesian Society. pp. 167–198. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Barber, Ian; Higham, Thomas F. G. (14 April 2021). "Archaeological science meets Māori knowledge to model pre-Columbian sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) dispersal to Polynesia's southernmost habitable margins". PLOS One. 16 (4): e0247643. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1647643B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247643. PMC 8046222. PMID 33852587.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Fox, Alex (12 April 2018). "Sweet potato migrated to Polynesia thousands of years before people did". Nature. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Jones, Terry L.; Storey, Alice A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth A.; Ramirez-Aliaga, Jose Miguel, eds. (2011). Polynesians in America: Pre-Columbian Contacts with the New World. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759120068.

- ^ Sharp, Andrew (1963). Ancient Voyagers in Polynesia, Longman Paul Ltd. pp. 122–128.

- ^ Finney, Ben R. (1976) "New, Non-Armchair Research". In Ben R. Finney, Pacific Navigation and Voyaging, The Polynesian Society Inc. p. 5.

- ^ a b Andersson, Axel (2010). A Hero for the Atomic Age: Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki Expedition. Peter Lang. ISBN 9781906165314.

- ^ Robert C. Suggs The Island Civilizations of Polynesia, New York: New American Library, p.212-224.

- ^ Kirch, P. (2000). On the Roads to the Wind: An archaeological history of the Pacific Islands before European contact. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- ^ Barnes, S.S.; et al. (2006). "Ancient DNA of the Pacific rat (Rattus exulans) from Rapa Nui (Easter Island)" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 33 (11): 1536–1540. Bibcode:2006JArSc..33.1536B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.02.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011.

- ^ Davis, Wade (2010) The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World, Crawley: University of Western Australia Publishing, p. 46.

- ^ Robert C. Suggs, The Island Civilizations of Polynesia, New York: New American Library, p.224.

- ^ Magelssen, Scott (March 2016). "White-Skinned Gods: Thor Heyerdahl, the Kon-Tiki Museum, and the Racial Theory of Polynesian Origins". TDR/The Drama Review. 60 (1): 25–49. doi:10.1162/DRAM_a_00522. S2CID 57559261.

- ^ Coughlin, Jenna (2016). "Trouble in Paradise: Revising Identity in Two Texts by Thor Heyerdahl". Scandinavian Studies. 88 (3): 246–269. doi:10.5406/scanstud.88.3.0246. JSTOR 10.5406/scanstud.88.3.0246. S2CID 164373747.

- ^ Wallin, Paul (8 July 2020). "Native South Americans were early inhabitants of Polynesia". Nature. 583 (7817): 524–525. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..524W. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01983-5. PMID 32641787. S2CID 220436442.

DNA analysis of Polynesians and Native South Americans has revealed an ancient genetic signature that resolves a long-running debate over Polynesian origins and early contacts between the two populations.

- ^ Wade, Lizzie (8 July 2020). "Polynesians steering by the stars met Native Americans long before Europeans arrived". Science. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Finney, Ben R. and Jones, Eric M. (1986). "Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience". University of California Press. p.176. ISBN 0-520-05898-4

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1995

- ^ Ian Breward in Farhadian, Charles E.; Hefner, Robert W. (2012). Introducing World Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 218–229. ISBN 9781405182485.; quote at p 228

- ^ "Polynesian Lexicon Project Online". Pollex.org.nz.

- ^ Matsuoka, Jon; Kelly, Terry (1988-12-01). "The Environmental, Economic, and Social Impacts of Resort Development and Tourism on Native Hawaiians". The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 15 (4). doi:10.15453/0191-5096.1868. ISSN 0191-5096. S2CID 141987142.

- ^ Tolland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. pp. 447–448.

It had been created by idealists who wanted to free Asia from the white man. As with many dreams, it was taken over and exploited by realists... Corrupted as the Co-Prosperity Sphere was by the militarists and their nationalist supporters, its call for pan-asianism remained relatively undiminished

- ^ Weinberg, L. Gerhard. (2005). Visions of Victory: The Hopes of Eight World War II Leaders p.62-65.

- ^ "NZ may be invited to join proposed 'Polynesian Triangle' ginger group", Pacific Scoop, 19 September 2011

- ^ "New Polynesian Leaders Group formed in Samoa", Radio New Zealand International, 18 November 2011

- ^ "American Samoa joins Polynesian Leaders Group, MOU signed". Samoa News. Savalii. 20 November 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Druett, Joan (1987). Tupaia – The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook's Polynesian Navigator. Random House, New Zealand. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-0313387487.

- ^ Druett, Joan (1987). Tupaia – The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook's Polynesian Navigator. Random House, New Zealand. pp. 218–233. ISBN 978-0313387487.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (June 5, 2007). "First Chickens in Americas Were Brought From Polynesia". The New York Times.

- ^ Storey, A. A.; Ramirez, J. M.; Quiroz, D.; Burley, D. V.; Addison, D. J.; Walter, R.; Anderson, A. J.; Hunt, T. L.; Athens, J. S.; Huynen, L.; Matisoo-Smith, E. A. (2007). "Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (25): 10335–10339. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410335S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703993104. PMC 1965514. PMID 17556540.

- ^ Gongora, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Mobegi, V. A.; Jianlin, H.; Alcalde, J. A.; Matus, J. T.; Hanotte, O.; Moran, C.; Austin, J. J.; Ulm, S.; Anderson, A. J.; Larson, G.; Cooper, A. (2008). "Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (30): 10308–10313. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10510308G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801991105. PMC 2492461. PMID 18663216.

- ^ Lewis, David. "A Return Voyage Between Puluwat and Saipan Using Micronesian Navigational Techniques". In Ben R. Finney (1976), Pacific Navigation and Voyaging, The Polynesian Society Inc.

- ^ Wilmé, Lucienne; Waeber, Patrick O.; Ganzhorn, Joerg U. (February 2016). "Marine turtles used to assist Austronesian sailors reaching new islands". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 339 (2): 78–82. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2015.12.001. ISSN 1631-0691. PMID 26857090.

- ^ Bryan, E.H. (1938). "Marshall Islands Stick Chart" (PDF). Paradise of the Pacific. 50 (7): 12–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

Further reading

edit- Ellis, William (1829). Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the South Sea Islands, Volume 1. Fisher, Son & Jackson.

- Ellis, William (1829). Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the South Sea Islands, Volume 2. Fisher, Son & Jackson.

- Ellis, William (1832). Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the South Sea Islands, Volume 3 (Second ed.). Fisher, Son & Jackson.

- Gatty, Harold (1999). Finding Your Ways Without Map or Compass. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-40613-8.

External links

edit- The dictionary definition of polynesia at Wiktionary

- Media related to Polynesia at Wikimedia Commons

- Interview with David Lewis (archived 1 May 2013)

- Lewis commenting on Spirits of the Voyage (archived 1 November 2012)

- Useful introduction to Maori society, including canoe voyages (archived 17 July 2013)

- Obituary: David Henry Lewis—including how he came to rediscover Pacific Ocean navigation methods