South Orange is a historic suburban village adjacent to Newark in Essex County, New Jersey. It was known as the Township of South Orange Village from October 1978 until April 25, 2024. As of the 2020 United States census, the village population was 18,484,[10][11] an increase of 2,286 (+14.1%) from the 2010 census count of 16,198,[19][20] which in turn reflected a decline of 766 (−4.5%) from the 16,964 counted in the 2000 census.[21] Seton Hall University is located in the township.

South Orange, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| South Orange Village (until April 25, 2024)[1] | |

South Orange village hall | |

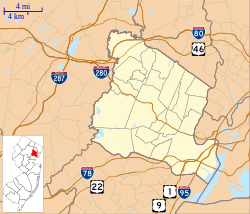

Interactive map of South Orange | |

Location in Essex County Location in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40°44′56″N 74°15′41″W / 40.748811°N 74.261512°W[2][3] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Essex |

| Incorporated | May 4, 1869 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special charter |

| • Body | Board of Trustees |

| • Mayor | Sheena C. Collum[4][5] |

| • Administrator | Julie Doran[6] |

| • Village Clerk | Ojetti E. Davis[7] |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.85 sq mi (7.38 km2) |

| • Land | 2.85 sq mi (7.37 km2) |

| • Water | <0.01 sq mi (<0.01 km2) 0.07% |

| • Rank | 349th of 565 in state 17th of 22 in county[2] |

| Elevation | 138 ft (42 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 18,484 |

| 18,208 | |

| • Rank | 147th of 565 in state 13th of 22 in county[13] |

| • Density | 6,494.7/sq mi (2,507.6/km2) |

| • Rank | 81st of 565 in state 11th of 22 in county[13] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code(s) | 973 and 862[16] |

| FIPS code | 3401369274[2][17][18] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1867376[9] |

| Website | www |

"The time and circumstances under which the name South Orange originated will probably never be known," wrote historian William H. Shaw in 1884, "and we are obliged to fall back on a tradition, that Mr. Nathan Squier first used the name in an advertisement offering wood for sale" in 1795.[22] Other sources attribute the derivation for all of the Oranges to King William III, Prince of Orange.[23]

Of the 564 municipalities in New Jersey, South Orange Village is one of only four with a village type of government; the others are Loch Arbour, Ridgefield Park and Ridgewood.[24]

On March 11, 2024, the governing body adopted a change to its charter under which "township" will be dropped from the municipality's name, the name of the governing body and its leader will be the council and mayor (rather than board of trustees and president of the board of trustees) and municipal elections will be shifted from May to November (which will shift term-end dates for all current elected officials from May to December 31); these changes will take full effect on April 25, 2024, after 45 days have passed from the adoption of the ordinance.[25]

History

editSouth Orange Village dates back to May 4, 1869, when it was formed within South Orange Township (now Maplewood). On March 4, 1904, the Village of South Orange was created by an act of the New Jersey Legislature and separated from South Orange Township.[26] In 1978, the village's name was changed by referendum to "The Township of South Orange Village", becoming the first of more than a dozen Essex County municipalities to reclassify themselves as townships in order take advantage of federal revenue sharing policies that allocated townships a greater share of government aid to municipalities on a per capita basis.[27][28][29]

What is now South Orange was part of a territory purchased from the Lenape Native Americans in 1666 by Robert Treat, who founded Newark that year on the banks of the Passaic River. The unsettled areas north and west of Newark were at first referred to as the uplands. South Orange was called the Chestnut Hills for a time.[22]

There are two claimants to the first English settlement in present-day South Orange. In 1677 brothers Joseph and Thomas Brown began clearing land for a farm in the area northwest of the junction of two old trails that are now South Orange Avenue and Ridgewood Road. A survey made in 1686 states, "note this Land hath a House on it, built by Joseph Brown and Thomas Brown, either of them having an equal share of it" located at the present southwest corner of Tillou Road and Ridgewood Road. Minutes of a Newark town meeting of September 27, 1680, record that "Nathaniel Wheeler, Edward Riggs, and Joseph Riggs, have a Grant to take up Land upon the Chesnut Hill by Rahway River near the Stone House". The phrasing shows that a stone house already existed near (not on) the property. Joseph Riggs (seemingly the son of Edward Riggs) had a house just south of the Browns' house, at the northwest corner of South Orange Avenue and Ridgewood Road, according to a road survey of 1705. The same road survey locates Edward Riggs's residence near Millburn and Nathaniel Wheeler's residence in modern West Orange at the corner of Valley Road and Main Street.[22]

Wheeler's property in South Orange extended east of the Rahway River including the site of an old house now known as the "Stone House", standing on the north side of South Orange Avenue just to the west of Grove Park. By 1756 or earlier this property was owned by Samuel Pierson. A survey of adjoining property in 1767 mentions "Pierson's house" forming accidentally the earliest documentation of a house on the property, which may be much older. Bethuel Pierson, son of Samuel, lived in this house and when he inherited it in 1773/74 he was said to live "at the mountain plantation by a certain brook called Stone House Brook." Sometime during his ownership (he died in 1791) "Bethuel Pierson had a stone addition added to his dwelling-house, which he caused to be dedicated by religious ceremonies". This would appear to be the stone-walled portion of the "Stone House".[22] Stone House Brook runs west along the north side of the east–west road, past the "Stone House" and joining the Rahway River at about the location of the Brown and Riggs houses already noted. The oldest parts of the Pierson house are the oldest surviving structure in South Orange.[30]

A deed of 1800 locates a property as being in "the Township of Newark, in the Parish of Orange, at a place called South Orange", marking the end of the name Chestnut Hills. Orange had been named after the ruler of England, William of Orange. Most of modern South Orange became part of Orange Township in 1806, part of Clinton Township in 1834, and part of South Orange Township in 1861. South Orange Village split off from South Orange Township in 1869 due to the desire for extensive privileges in the conduct of public affairs. South Orange Village became a haven for those who wanted freedom from the commotion of city life after the end of the American Civil War.[31] A majority of South Orange Township became what is now known as Maplewood, New Jersey.[32] Gordon's Gazetteer circa 1830 describes the settlement as having "about 30 dwellings, a tavern and store, a paper mill and Presbyterian church".[33]

A country resort called the Orange Mountain House was established in 1847 on Ridgewood Road in present-day West Orange, where guests could enjoy the "water cure" from natural spring water and walk in the grounds that extended up the slope of South Mountain. The hotel burned down in 1890. The only remnants today are the names of Mountain Station and the Mountain House Road leading west from it to the site of the hotel.[34]

South Orange could be reached by the Morris and Essex Railroad which opened in 1837 between Newark and Morristown. As of 1869, the M&E became part of the main line of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad which ran from Hoboken to Buffalo with through trains to Chicago.[35]

The Montrose neighborhood was developed after the Civil War. Its large houses on generous lots attracted wealthy families from Newark and New York City during the decades from 1870 to 1900.[36] The Orange Lawn Tennis Club was founded in 1880 at a location in Montrose, and in 1886 it was the location of the first US national tennis championships.[37] The club moved to larger grounds on Ridgewood Road in 1916. Major tournament events were held at the club throughout the grass court era, and even into the mid-1980s professional events would occasionally be held there.[38]

What is now the Baird Community House was up until about 1920 the clubhouse for a golf course that encompassed what is now Meadowlands Park. Until regrading was performed during the 1970s, the outline of one of the course's sand traps was still visible near the base of Flood's Hill, a spot that has historically been one of the favorite sledding spots in Essex County.[39]

The construction of Village Hall in 1894 and the "old" library building in 1896 indicate how the village was growing by that date.[34] Horsecar service from Newark started in 1865, running via South Orange Avenue to the station. Electric trolley cars began running the line in 1893 and by about 1900 a branch of this line also ran down Valley Street into Maplewood. Another separate trolley line, eventually dubbed the "Swamp Line", ran from the west side of the station north through what is now park land and along Meadowbrook Lane into West Orange where it ended at Main Street.[40] An old postcard photo shows a station shelter at Montrose Ave. The DL&W rebuilt the railroad through town in 1914–1916, raising the tracks above street level and opening new station buildings at South Orange and Mountain Station. In September 1930, a frail Thomas Edison (he would die about a year later) inaugurated electric train service on the M&E between Hoboken and South Orange, with further extensions of service to Morristown and Dover being initiated over the coming months.[41][page needed]

The South Orange Library Association was organized by William Beebe, president of the Republican Club, where on November 14, 1864, a group of men and women met. Books were donated and the library was established in a corner room on the second floor of the Republican Club where it remained until 1867 when it was moved to a second floor room of the building next door on South Orange Avenue, near Sloan Street. It stayed there until 1884, when the building, with the library still on its second floor, was moved by horses up South Orange Avenue to the northwest corner of Scotland Road. Although supported as yet only by members' dues and a few gifts of money which were put into an endowment fund, in 1886 a new association was formed to establish a free circulating library and reading room which took over the loan books and other property of the old association. It was during this period, before Village Hall was built, that Village Trustees met in the Library's room. On May 1, 1889, the library was moved to a ground floor space at 59 South Orange Avenue.[42]

At an annual meeting in 1895, Library Trustees considered the question of obtaining a library building and Eugene V. Connett's offer of a library site on the corner of Scotland Road and Taylor Place, once a $7,500 subscription was met (equivalent to $76,000 in 2023). On May 8, 1896, the library was moved into the building on that corner. A referendum held on April 27, 1926, showed that citizens had voted ten to one in favor of the town taking over full support of the library. It thereupon became "The South Orange Public Library." In February 1929, the Village Trustees passed an ordinance providing funds to construct a rear wing on the library and to provide a Children's Room in the basement, book stacks and a balcony on the floor above, together with rehabilitation work on the older part of the building. In November 1968, the new library building on the corner of Scotland Road and Comstock Place was dedicated.[42]

Good transportation and a booming economy caused South Orange and neighboring communities to begin a major transformation in the 1920s into bedroom communities for Newark and New York City. Large houses were built in the blocks around the Orange Lawn Tennis club, while in other areas, especially south of South Orange Avenue, more modest foursquare houses were constructed. The only large area not developed by 1930 was the high ground west of Wyoming Avenue.[citation needed]

There were two rock quarries within the village supplying trap rock for construction. Kernan's operated as late as the 1980s at the top of Tillou Road. The village's other larger businesses were lumber and coal yards clustered around the railroad station that supplied them. The business district is still located in the blocks just east of the station.

The old Morris and Essex Railroad is operated today by NJ Transit. Midtown Direct, initiated in 1996, offers service directly into Penn Station in Midtown Manhattan, and has since caused a surge in real estate prices as the commute time to midtown dropped from about 50 minutes to 35, as the service eliminated the need for passengers to transfer to PATH trains at Hoboken. As a result, demand for commuter parking permits in lots adjoining the train and bus stations is extremely high, with a waiting list as long as five years for commuter parking spots.[43]

Historic designations

editSouth Orange has a number of places listed on the State and National Historic Registers.

- Old Stone House by the Stone House Brook (ID#1364), 219 South Orange Avenue – First mentioned in a document in 1680, the house has been owned by the village which has sought to sell it to ensure that it will be restored.[44]

- Baird Community Center (ID#3146), 5 Mead Street – The Baird offers arts programs, including the Pierro Gallery of South Orange and The Theater on 3, along with preschool and other educational programming.[45]

- Chapel of the Immaculate Conception (ID#4121), 400 South Orange Avenue, dates back to Seton Hall's move to South Orange and serves as the center focus of its campus.[46]

- Eugene V. Kelly Carriage House (Father Vincent Monella Art Center) (ID#1360), Seton Hall University, South Orange Avenue[47]

- Montrose Park Historic District (ID#3147), roughly bounded by South Orange Avenue, Holland Road, the City of Orange boundary and the NJ Transit railroad right-of-way

- Mountain Station Railroad Station (ID#1361), 449 Vose Avenue

- Old Main Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Historic District (ID#3525), Morris and Essex Railroad Right-of-Way (NJ Transit Morristown Line), from Hudson, Hoboken City to Warren, Washington Township, and then along Warren Railroad to the Delaware River.

- Prospect Street Historic District (ID#4), bounded by South Orange Avenue on the north, Tichenor Avenue on the east, Roland Avenue on the south and railroad track on the west

- South Orange Fire Department (ID#41), First Avenue and Sloan Avenue

- South Orange station (ID#1362), at 19 Sloan Street, was constructed in 1916 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.[48]

- South Orange Village Hall (ID#1363), constructed in 1894 at the corner of South Orange Avenue and Scotland Road[49]

- Temple Sharey Tefilo-Israel (ID#78), 432 Scotland Road, dates back to the formation of Temple Sharey Tefilo in Orange in 1874 and of Temple Israel in South Orange in 1948, which acquired the Kip-Riker mansion, the congregation's current home, the following year.[50]

Local character

editThe village is one of only a few in New Jersey to retain gas light street illumination (others include Riverton, Palmyra, Trenton Mill Hill neighborhood, and Glen Ridge). The gaslight, together with the distinctive Village Hall, has long been the symbol of South Orange. Many of the major roads in town do have modern mercury vapor streetlights (built into gaslight frames), but most of the residential sections of the town are still gas-lit. A proposal to replace all the gaslights in town with electric streetlights was explored as both a cost-saving and security measure during the 1970s. And although the changeover to electric was rejected at the time, the light output of the lamps was increased to provide more adequate lighting. There have been claims that South Orange has more operating gaslights than any other community in the United States. In 2010, the village initiated a project that would automatically shut the lamps in the morning and light them at dusk, as part of an effort to save as much as $400,000 each year in energy costs for the 1,438 gas lamps across the village.[51] As of 2019, these devices have not been installed.

Architecture is extremely varied. Most of the town is single-family wood-framed houses, however, there are a few apartment buildings from various eras as well as townhouse-style condominiums of mostly more recent vintage. Houses cover a range that includes every common style of the Mid-Atlantic United States since the late nineteenth century, and in sizes that range from brick English Cottages to giant Mansard-roofed mansions. Tudor, Victorian, Colonial, Ranch, Modern, and many others are all to be found. Most municipal government structures date from the 1920s, with a few being of more modern construction.

Many residents commute to New York City, but others work locally or in other parts of New Jersey. South Orange has a central business district with restaurants, banks, and other retail and professional services. There are a few small office buildings, but no large-scale enterprise other than Seton Hall University.

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the village had a total area of 2.85 square miles (7.4 km2), including 2.85 square miles (7.4 km2) of land and <0.01 square miles (0.026 km2) of water (0.07%).[2][3]

South Orange is bordered by the Essex County municipalities of Maplewood, Newark, West Orange, Orange, and East Orange.[52][53] South Orange also comes close to bordering both Livingston and Millburn.

The East Branch of the Rahway River, which originates in West Orange, flows through the entire length of the village. Most of the time it is a trickle but flows can be heavy after rain.[54] In the past it would occasionally overflow its banks and flood low-lying parts of town an issue that was addressed by United States Army Corps of Engineers flood control projects that remediated the problem in the mid-1970s.[55]

The western part of the town sits on the eastern slope of South Mountain (elevation <660 feet (200 m)), leveling into a small valley near the central business district. At the top of the slope, the western edge of the town runs along the eastern border of South Mountain Reservation. South Orange contains the historic Montrose district, Newstead, Tuxedo Park, and Wyoming sections.[56] Seton Hall University is located in the southeast quadrant of the township.[57]

Climate

editSouth Orange has a humid continental climate (Dfa).

| Climate data for South Orange | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

39.2 (4.0) |

46.8 (8.2) |

57.9 (14.4) |

68.5 (20.3) |

77.2 (25.1) |

83.8 (28.8) |

81.9 (27.7) |

75 (24) |

63 (17) |

50.9 (10.5) |

41.9 (5.5) |

60.1 (15.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.3 (−4.3) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

33.3 (0.7) |

43.3 (6.3) |

53.1 (11.7) |

61.5 (16.4) |

67.8 (19.9) |

67.3 (19.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

50.4 (10.2) |

38.8 (3.8) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

46.4 (8.0) |

| Source: [58] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,178 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,106 | 42.6% | |

| 1900 | 4,608 | 48.4% | |

| 1910 | 6,014 | 30.5% | |

| 1920 | 7,274 | 21.0% | |

| 1930 | 13,630 | 87.4% | |

| 1940 | 13,742 | 0.8% | |

| 1950 | 15,230 | 10.8% | |

| 1960 | 16,175 | 6.2% | |

| 1970 | 16,971 | 4.9% | |

| 1980 | 15,864 | −6.5% | |

| 1990 | 16,390 | 3.3% | |

| 2000 | 16,964 | 3.5% | |

| 2010 | 16,198 | −4.5% | |

| 2020 | 18,484 | 14.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 18,208 | [10][12] | −1.5% |

| Population sources: 1880–1890[59] 1880–1920[60] 1890–1910[61] 1880–1930[62] 1940–2000[63] 2000[64][65] 2010[19][20][66] 2020[10][11] | |||

South Orange is a wealthy and diverse village and has one of the largest Jewish communities in Essex County, along with nearby Livingston and Millburn.[67]

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[68] | Pop 2010[69] | Pop 2020[70] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 9,871 | 9,231 | 10,510 | 58.19% | 56.99% | 56.86% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 5,150 | 4,484 | 3,803 | 30.36% | 27.68% | 20.57% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 16 | 18 | 11 | 0.09% | 0.11% | 0.06% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 659 | 829 | 1,228 | 3.88% | 5.12% | 6.64% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0.03% | 0.01% | 0.01% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 51 | 91 | 282 | 0.30% | 0.56% | 1.53% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 375 | 551 | 1,044 | 2.21% | 3.40% | 5.65% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 837 | 993 | 1,604 | 4.93% | 6.13% | 8.68% |

| Total | 16,964 | 16,198 | 18,484 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editThe 2010 United States census counted 16,198 people, 5,516 households, and 3,756 families in the township. The population density was 5,672.8 people per square mile (2,190.3 people/km2). There were 5,815 housing units at an average density of 2,036.5 units per square mile (786.3 units/km2). The racial makeup was 60.19% (9,750) White, 28.66% (4,642) Black or African American, 0.14% (23) Native American, 5.16% (836) Asian, 0.01% (1) Pacific Islander, 1.77% (287) from other races, and 4.07% (659) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.13% (993) of the population.[19]

Of the 5,516 households, 35.2% had children under the age of 18; 54.1% were married couples living together; 10.3% had a female householder with no husband present and 31.9% were non-families. Of all households, 24.3% were made up of individuals and 8.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.24.[19]

22.9% of the population were under the age of 18, 15.2% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 27.2% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37.2 years. For every 100 females, the population had 93.7 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 90.4 males.[19]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $123,373 (with a margin of error of +/− $7,803) and the median family income was $147,532 (+/− $9,218). Males had a median income of $86,122 (+/− $7,340) versus $71,625 (+/− $9,896) for females. The per capita income for the township was $49,607 (+/− $4,022). About 2.5% of families and 7.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.4% of those under age 18 and 4.5% of those age 65 or over.[71]

2000 census

editAs of the 2000 United States census[17] there were 16,964 people, 5,522 households, and 3,766 families residing in the township. The population density was 5,945.3 inhabitants per square mile (2,295.5/km2). There were 5,671 housing units at an average density of 1,987.5 units per square mile (767.4 units/km2). The racial makeup of the township was 60.41% White, 31.30% African American, 0.09% Native American, 3.89% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 1.57% from other races, and 2.71% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.93% of the population.[64][65]

There were 5,522 households, out of which 33.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.2% were married couples living together, 10.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.8% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.26.[64][65]

In the township the population was spread out, with 22.3% under the age of 18, 17.5% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 22.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.1 males.[64][65]

The median income for a household in the township was $83,611, and the median income for a family was $107,641. Males had a median income of $61,809 versus $42,238 for females. The per capita income for the township was $41,035. About 1.9% of families and 5.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.6% of those under age 18 and 5.4% of those age 65 or over.[64][65]

Parks and recreation

editThe village has a municipal swimming pool open to all residents. In most area communities, municipal pool memberships are restricted or costly, but the pool in South Orange was built on land willed by a wealthy resident to the town for common use and under the terms of the deal the pool had to remain inexpensive for the residents. Residents may purchase an annual pass for a fee of $35, which provides access to the South Orange Community Pool and full access to all other community facilities and programs;[72] non-residents may use the pool for a small fee on a per visit basis on a guest pass that must be purchased by a resident. The original pool, built in the 1920s, is among the first free community pools to be built in the United States, and was replaced by an Olympic-size pool in 1972.[73]

The South Orange River Greenway is currently under construction. The River Greenway will be a promenade for bicyclists and pedestrians that will connect part of West Third Street in South Orange with West Parker Avenue in Maplewood. Several abandoned buildings will be removed near the South Orange Department of Public Works facility to make way for the River Greenway.[74]

Parks in the village include Grove Park, New Waterlands Park, Flood's Hill, Cameron Field and Farrell Field.[75]

Arts and culture

editThe Baird Center, located in Meadowland Park, houses the South Orange Department of Recreation and Cultural Affairs, and hosts many activities. Most of the department's programs are housed in The Baird or in adjoining Meadowland Park. The center offers arts programs, including the Pierro Gallery of South Orange, The Theater on 3, and other arts spaces, along with preschool and other educational, arts and recreational programming.[45] The Baird Center is undergoing extensive renovation starting in late 2019. The Baird hosts events together with SOPAC, including the long-running Giants of Jazz concert series.[76][77]

The Pierro Gallery of South Orange, located within The Baird and operating as part of the South Orange Department of Recreation and Cultural Affairs, encourages community involvement in the visual arts and exhibits the non-commercial works of contemporary artists working in the field, in addition to providing arts education and serving local artists. Exhibitions often include the work of area artists, with a juried "Essex Exposed" exhibition conducted twice each year offering materials created by artists from Essex County.[78]

South Orange Performing Arts Center (SOPAC) is located next to the South Orange station. The performance venue is a 415-seat proscenium theater, with a five-screen cinema, The Village at SOPAC, as well as a dance studio/rental space in the same complex.[79]

SOPAC presents music, family, dance, theater, and comedy programs throughout the year. In partnership with Seton Hall University, SOPAC has presented Seton Hall Arts Council events, including a Classical Concert Series, Jazz 'n the Hall, and Seton Hall Theatre—student theater productions.

The plans for SOPAC were first conceived in the mid-1990s as part of an effort by the village to develop the downtown area. Seton Hall University partnered with SOPAC and construction in August 2004. The complex opened in November 2006 to the general public.[80]

Founded in 1949, the South Orange Symphony is a full-sized symphony orchestra made up of volunteer amateur and semi-professional musicians with a wide range of musical backgrounds led by a professional conductor. The ensemble plays repertoire that covers the full range of classical literature from the 18th century to today, and presents three free concerts each year in Sterling Hall at the South Orange Middle School.[81]

Government

editSouth Orange provides police, a library of over 90,000 volumes, a municipal pool, a recreation center, parks, baseball diamonds, tennis courts, trash and yard waste removal provided by contractors, Public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable TV, among others. The school board is shared with adjacent Maplewood.

Fire protection in the village is provided by the South Essex Fire Department, which was formed in July 2022 as the successor to the former Maplewood Fire Department and South Orange Fire Department.[82]

The South Orange Rescue Squad, formed in 1952, provides 911 EMS services to residents on a volunteer basis.[83]

Local government

editSouth Orange is governed under a special charter granted by the New Jersey Legislature. The village is one of 11 municipalities (of the 564) statewide that operate under a special charter.[84][85] The governing body is comprised of a six-member village council and a mayor, all of which are unpaid positions. Council members are elected in non-partisan elections on an at-large basis to staggered four-year terms of office with three seats up for election in odd-numbered years. The mayor serves a four-year term of office.[8] Local political parties are formed on an ad-hoc basis, generally focused on key issues of local concern; national political parties do not officially participate in village elections.

As of 2024[update], the mayor of South Orange is Sheena Collum, whose term of office ends May 17, 2027.[4] Members of the Village Council are Braynard "Bobby" Brown (2025), Jennifer Greenberg (2027), Karen Hartshorn Hilton (2025), Bill Haskins (2025), Summer Jones (2027) and Olivia Lewis-Chang (2027).[86][87][88][89][90]

In September 2022, Steve Schnall was appointed to fill the seat expiring in December 2023 that had been held by Bob Zuckerman until he resigned from office as he wasmoving out of South Orange.[91]

In the May 2015 municipal election, Sheena Collum was elected as Village President, making her the first woman to serve in the position, while Deborah Davis Ford, Howard Levison and Mark Rosner ran unopposed and won new terms of office on the board of trustees.[92]

With three incumbents not running for re-election in the May 2013 election, the slate of Walter Clarke, Sheena Collum and Stephen Schnall running together as South Orange 2013 were elected to four-year terms, with the support of Village President Alex Torpey.[93]

In the municipal election held in May 2011, with fewer than 10% of the registered voters casting ballots, 23-year-old Alex Torpey was elected as the youngest Village President in the history of South Orange by a margin of 14 votes, while trustees Deborah Davis Ford, Howard Levison and Mark Rosner were re-elected to four-year terms of office, having run unopposed.[4][94][95] In the 2009 elections with two incumbents not running for re-election, Michael Goldberg was elected to another four-year term, along with newcomers Janine Bauer and Nancy Gould, by a nearly 2–1 margin.[96]

Federal, state, and county representation

editSouth Orange is located in the 11th Congressional District[97] and is part of New Jersey's 28th state legislative district.[98]

Prior to the 2010 Census, South Orange had been split between the 8th Congressional District and the 10th Congressional District, a change made by the New Jersey Redistricting Commission that took effect in January 2013, based on the results of the November 2012 general elections.[99]

For the 118th United States Congress, New Jersey's 11th congressional district is represented by Mikie Sherrill (D, Montclair).[100] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2027) and Andy Kim (Moorestown, term ends 2031).[101][102]

For the 2024-2025 session, the 28th legislative district of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Renee Burgess (D, Irvington) and in the General Assembly by Garnet Hall (D, Maplewood) and Cleopatra Tucker (D, Newark).[103]

Essex County is governed by a directly elected county executive, with legislative functions performed by the Board of County Commissioners. As of 2025[update], the County Executive is Joseph N. DiVincenzo Jr. (D, Roseland), whose four-year term of office ends December 31, 2026.[104] The county's Board of County Commissioners is composed of nine members, five of whom are elected from districts and four of whom are elected on an at-large basis. They are elected for three-year concurrent terms and may be re-elected to successive terms at the annual election in November.[105] Essex County's Commissioners are:

Robert Mercado (D, District 1 – Newark's North and East Wards, parts of Central and West Wards; Newark, 2026),[106] A'Dorian Murray-Thomas (D, District 2 – Irvington, Maplewood and parts of Newark's South and West Wards; Newark, 2026),[107] Vice President Tyshammie L. Cooper (D, District 3 - Newark: West and Central Wards; East Orange, Orange and South Orange; East Orange, 2026),[108] Leonard M. Luciano (D, District 4 – Caldwell, Cedar Grove, Essex Fells, Fairfield, Livingston, Millburn, North Caldwell, Roseland, Verona, West Caldwell and West Orange; West Caldwell, 2026),[109] President Carlos M. Pomares (D, District 5 – Belleville, Bloomfield, Glen Ridge, Montclair and Nutley; Bloomfield, 2026),[110] Brendan W. Gill (D, at large; Montclair, 2026),[111] Romaine Graham (D, at large; Irvington, 2026),[112] Wayne Richardson (D, at large; Newark, 2026),[113] Patricia Sebold (D, at-large; Livingston, 2026).[114][115][116][117][118]

Constitutional officers elected countywide are: Clerk Christopher J. Durkin (D, West Caldwell, 2025),[119][120] Register of Deeds Juan M. Rivera Jr. (D, Newark, 2029),[121][122] Sheriff Amir Jones (D, Newark, 2027),[123][124] and Surrogate Alturrick Kenney (D, Newark, 2028).[125][126]

Politics

editAs of 2019, there are a total of 13,564 registered voters in South Orange Village.[127]

In the 2012 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 83.1% of the vote (6,566 cast), ahead of Republican Mitt Romney with 16.1% (1,270 votes), and other candidates with 0.8% (62 votes), among the 7,962 ballots cast by the village's 12,623 registered voters (64 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 63.1%.[128][129] In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 81.1% of the vote (7,228 cast), ahead of Republican John McCain with 17.6% (1,569 votes) and other candidates with 0.6% (53 votes), among the 8,913 ballots cast by the village's 12,243 registered voters, for a turnout of 72.8%.[130] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 77.3% of the vote (6,641 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 21.9% (1,883 votes) and other candidates with 0.4% (45 votes), among the 8,590 ballots cast by the village's 10,990 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 78.2.[131]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Democrat Barbara Buono received 68.3% of the vote (3,314 cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 30.3% (1,469 votes), and other candidates with 1.4% (67 votes), among the 4,963 ballots cast by the village's 12,656 registered voters (113 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 39.2%.[132][133] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Democrat Jon Corzine received 74.6% of the vote (4,275 ballots cast), ahead of Republican Chris Christie with 19.5% (1,119 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 4.8% (273 votes) and other candidates with 0.5% (29 votes), among the 5,727 ballots cast by the village's 12,184 registered voters, yielding a 47.0% turnout.[134]

Education

editThe village shares a common school system, the South Orange-Maplewood School District, with the adjacent township of Maplewood. The district has a single high school (located in Maplewood, nearly on the border of the two towns), two middle schools, a central pre-school and neighborhood elementary schools, distributed between the two municipalities. As of the 2019–20 school year, the district, comprised of 11 schools, had an enrollment of 7,353 students and 576.1 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 12.8:1.[135] Schools in the district (with 2019–20 school enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[136]) are Montrose Early Childhood Center[137] (133 students, in PreK; located in Maplewood), Seth Boyden Elementary Demonstration School[138] (493 students, in grades K–5 located in Maplewood), Clinton Elementary School[139] (605, K–5; Maplewood), Jefferson Elementary School[140] (544, 3–5; Maplewood), Marshall Elementary School[141] (518, K–2; South Orange), South Mountain Elementary School[142] (647, K–5; South Orange), South Mountain Elementary School Annex[143] (NA, K–1; South Orange), Tuscan Elementary School[144] (K–5, 637; Maplewood), Maplewood Middle School[145] (827, 6–8; Maplewood), South Orange Middle School[146] (786, 6–8; South Orange) and Columbia High School[147] (1,967, 9–12; Maplewood).[148][149]

Private schools

editFounded in 1890, Our Lady of Sorrows School is a K–8 elementary school operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark.[150][151] The all-girls Marylawn of the Oranges Academy closed at the conclusion of the 2012–13 school year due to declining enrollment and fiscal challenges.[152]

Higher education

editSeton Hall University, which serves approximately 9,700 students, was founded in 1856 by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark and named after Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American Catholic saint. The Division I university is located along the east side of South Orange Avenue, the community's main boulevard.[153]

Transportation

editRoads and highways

editAs of May 2010[update], the village had a total of 48.76 miles (78.47 km) of roadways, of which 42.88 miles (69.01 km) were maintained by the municipality and 5.88 miles (9.46 km) by Essex County.[154]

The county roads serving South Orange include County Route 510 (South Orange Avenue)[155] and County Route 577 (Wyoming Avenue).[156] Principal local roads include Valley Street / Scotland Road, Irvington Avenue and Centre Street.[157]

Public transportation

editSouth Orange is served by two NJ Transit railroad stations: the South Orange station, located on South Orange Avenue near the intersection of Sloan Street[158] and the Mountain Station, located in the Montrose section of South Orange.[159] The two stations provide service along the Morris and Essex Line to Newark Broad Street Station and either to New York Penn Station (some stopping at Secaucus Junction) or Hoboken Terminal.[160]

NJ Transit operates three bus lines that run through South Orange. These include the 92 route which goes from South Orange train station to Branch Brook Park in Newark, and the 107 route which goes from South Orange Train Station to the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York City.[161] The 31 bus line, which travels between South Orange and Newark Penn Station, also makes stops along South Orange Avenue.[162]

There is a shuttle connecting South Orange to Livingston, timed with connecting Morristown Line trains.[163]

Local media

editWSOU-FM, "Seton Hall's Pirate Radio", is a non-commercial educational public radio station licensed to South Orange since 1948 with studios, offices, and transmitter on the campus of Seton Hall University while operating at 89.5 FM.[164]

The News-Record weekly newspaper reports on both South Orange and Maplewood.[165]

"The Village Green", a hyperlocal news site, reports on both South Orange and Maplewood, and includes a daily email newsletter.[166]

South Orange Patch provides local news and events and latest headlines.[167]

The Gaslight is a quarterly newsletter managed by the local government that focuses on the on-goings of South Orange, NJ. Additionally, the newsletter offers advertisements sponsoring local public figures, businesses and job opportunities for the general public.[168]

Community information

edit- The town was the first in the nation to have an affinity credit card, the idea of the municipal affinity credit card being originated by former village president William Calabrese.[169]

- When the town was wired for telephones and electricity in the early 20th century, the poles and wires were not allowed to run along the curb lines of streets as they do in most towns. In some sections they run along property lines in the middle of blocks, and in others they run underground. This is aesthetically pleasing but complicates access to the lines, and it delayed the introduction of cable television. Occasional proposals to replace gas lights with electric lights run across the obstacle that there is no source of electric power along the streets.[citation needed]

- The current 761, 762, and 763 telephone exchanges used for most lines in South Orange and Maplewood, originated as the exchange names South Orange 1,2, and 3.[citation needed]

- Until April 25, 2024, South Orange's full official name was the "Township of South Orange Village." This name was originally adopted in lieu of the Village of South Orange because it allowed South Orange to receive more federal aid that was directed to Townships during the 1970s as many federal authorities were unfamiliar with the New Jersey municipal system, in which a township is not formally different from any other municipal designation. Other municipalities in New Jersey also adopted similar strategies, notably the Township of the Borough of Verona.

- South Orange was the first municipality in New Jersey to recognize civil unions for homosexual couples. Exactly one hour after unions became legal in South Orange, they were recognized in neighboring Maplewood.[170]

Notable people

editReferences

edit- ^ Municipal Code, Township of South Orange Village. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e 2019 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Mayor Sheena C. Collum, South Orange Village. Accessed May 2, 2024.

- ^ 2023 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, updated February 8, 2023. Accessed February 10, 2023.

- ^ Administration, South Orange Village. Accessed March 22, 2024.

- ^ Clerk's Office, South Orange Village. Accessed March 22, 2024.

- ^ a b 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 125.

- ^ a b South Orange, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed April 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e QuickFacts for South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed January 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c Total Population: Census 2010 - Census 2020 New Jersey Municipalities, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Minor Civil Divisions in New Jersey: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023, United States Census Bureau, released May 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Population Density by County and Municipality: New Jersey, 2020 and 2021, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 1, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for South Orange, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Zip Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Area Codes for ORANGE, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed April 25, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 1, 2019.

- ^ Geographic Codes Lookup for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed April 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for South Orange Archived August 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Shaw, William H. History of Essex and Hudson Counties, Philadelphia: Everts and Peck, 1884.

- ^ Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- ^ Cerra, Michael F. "Forms of Government" Archived September 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Municipalities (publication of the New Jersey State League of Municipalities), March 2007. Accessed July 21, 2013.

- ^ "The quirky, bureaucratic reason this N.J. town just changed its official name", NJ Adbance Media for NJ.com, March 24, 2024. Accessed March 24, 2024. "Since 1977, what most people know as quaint South Orange Village has been officially known by the clunky name of The Township of South Orange Village. Blame it on bureaucracy, which enticed the village Board of Trustees to change South Orange to a township 46 years ago so that it could qualify for federal grants.... The village no longer has to call itself a township in order to qualify for federal money, so on March 11, the village Board of Trustees adopted a charter change that lops off ‘township” and restores the town’s original name, South Orange Village, adopted in 1869.... But the new charter abolishes the office of president and the Board of Trustees and replaces them with a mayor and council. It also moves elections from May to November. 'People are already calling me mayor,' Collum said, although she believes the charter change doesn’t take effect until 45 days after the March 11 adoption."

- ^ Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 132. Accessed May 30, 2024.

- ^ "Chapter VI: Municipal Names and Municipal Classification" Archived September 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, p. 73. New Jersey State Commission on County and Municipal Government, 1992. Accessed September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Removing Tiering From The Revenue Sharing Formula Would Eliminate Payment Inequities To Local Governments", Government Accountability Office, April 15, 1982. Accessed September 24, 2015. "In 1978, South Orange Village was the first municipality to change its name to the 'township' of South Orange Village effective beginning in entitlement period 10 (October 1978 to September 1979). The Borough of Fairfield in 1978 changed its designation by a majority vote of the electorate and became the 'Township of Fairfield' effective beginning entitlement period 11 (October 1979 to September 1980).... However, the Revenue Sharing Act was not changed and the actions taken by South Orange and Fairfield prompted the Town of Montclair and West Orange to change their designation by referendum in the November 4, 1980, election. The municipalities of Belleville, Verona, Bloomfield, Nutley, Essex Fells, Caldwell, and West Caldwell have since changed their classification from municipality to a township."

- ^ Narvaez, Alfonso A. "New Jersey Journal", The New York Times, December 27, 1981. Accessed September 24, 2015. "Under the Federal system, New Jersey's portion of the revenue sharing funds is disbursed among the 21 counties to create three 'money pools.' One is for county governments, one for 'places' and a third for townships. By making the change, a community can use the 'township advantage' to get away from the category containing areas with low per capita incomes."

- ^ "College Life, Commuters and Gaslights - Historic South Orange, New Jersey". nj.cooperatornews.com. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Pierson, David Lawrence. “South Orange Village.” History of the Oranges, by David Lawrence. Pierson, vol. 3, Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1922, pp. 515–533.

- ^ Pierson, David Lawrence. “South Orange.” History of the Oranges, by David Lawrence. Pierson, vol. 3, Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1922, pp. 505–514.

- ^ Welak, Naoma. South Orange: Images of American, Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002. ISBN 9780738509747.

- ^ a b Herman, Beatrice P. The Trail to Upland Plantations, Worrall, 1976

- ^ Morris & Essex Railroad Co., hoboken.pastperfectonline.com. Accessed April 25, 2021.

- ^ Zakalak, Ulana D. Montrose Park History, Montrose Park Historic District Association. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ "Jersey Tennis Players; Opening of the Annual Tournamernt in the Orange Grounds.", The New York Times, June 29, 1886. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Our History". Orange Lawn Tennis Club. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ "Local History: The Lone Oak Golf Course". South Orange, NJ Patch. June 19, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Edward Hamm, Jr, The Public Service Trolley Lines in New Jersey, Polo IL: Transportation Trails, 1991

- ^ Taber, Thomas Townsend; Taber, Thomas Townsend III (1980). The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad in the Twentieth Century. Vol. 1. Muncy, PA: Privately printed. ISBN 0-9603398-2-5.

- ^ a b "A Brief History of the South Orange Library - South Orange Public Library Wiki". localhistory.sopl.org. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "Waiting Lists | South Orange Village, NJ". www.southorange.org. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Khavkine, Richard. "South Orange to sell Old Stone House for preservation, refurbishment", The Star-Ledger, March 24, 2010. Accessed March 25, 2012. "The earliest reference to the Old Stone House dates to Sept. 27, 1680, when it was mentioned in the minutes of a Newark town meeting to discuss and distribute land grants, according to the South Orange Historical and Preservation Society."

- ^ a b The Baird, South Orange Village. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Immaculate Conception Chapel: The Dream, Seton Hall University. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Eugene V. Kelly Carriage House - Nomination Form, National Register of Historic Places. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ "South Orange Train Station 100th Anniversary Celebration October 1", The Village Green of Maplewood and South Orange, September 27, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. "Built in 1916 by architect Frank J. Nies, the South Orange Train Station was designed in the Renaissance Revival style and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. Today, it is the busiest stop on the Morris & Essex Line with over 4,000 boarders a day."

- ^ Inventory - Nomination Form for South Orange Village Hall, National Register of Historic Places. Accessed April 15, 2015.

- ^ History, Temple Sharey Tefilo-Israel. Accessed June 29, 2022. "Our congregation’s history began in 1874, when 10 merchants from Orange, New Jersey met in a small room above a storefront on Cleveland Street to establish Congregation Sharey Tefilo of Orange.... In April of 1948, 229 families from Sharey Tefilo, citing the need for a new type of religious experience, established Temple Israel in South Orange. Within a year, Temple Israel’s congregation had purchased the historic Kip-Riker mansion on two and a half acres of land, the site of our congregation today."

- ^ Khavkine, Richard. "South Orange tests device to automate gas lamps", The Star-Ledger, August 22, 2010. Accessed October 21, 2015. "The hope is that after a yearlong testing period, the battery-powered device, developed by PSE&G together with the Northeast Gas Association and others, will be installed in each of the village's 1,438 gas lamps."

- ^ Areas touching South Orange, MapIt. Accessed March 9, 2020.

- ^ Municipalities, Essex County, New Jersey Register of Deeds and Mortgages. Accessed March 9, 2020.

- ^ Protecting and restoring the Rahway River and its ecosystem, Rahway River Association. Accessed March 24, 2012. "There are 24 municipalities in the Rahway River watershed including Maplewood, Millburn, South Orange and West Orange in Essex County, Carteret and Edison in Middlesex County and Cranford, Mountainside, Springfield and Rahway in Union County."

- ^ Meagher, Tom. "South Orange project aims to spruce up river banks", The Star-Ledger, August 10, 2009. Accessed March 25, 2012. "But the East Branch of the Rahway is once again being thought of as a river: The second phase of a greenway project will turn its banks into a promenade and bicycle path and, it's hoped, the waterway into an ecological prize.... While the Army Corps of Engineers helped curtail some of the waterway's chronic flooding about three decades ago, it also compromised its aesthetics, Barrett said."

- ^ DePalma, Anthony. "If You're Thinking of Living in: South Orange", The New York Times, January 9, 1983. Accessed August 22, 2013. "The village's 2.8 square miles are split unofficially into three sections: the older, Victorian homes in the southeast corner; a large neighborhood of comfortable, middle-class residences filling in the valley from Seton Hall University through the busy village center and train station area up to the foot of South Mountain; and the mountain itself, where newer, larger and more expensive homes have been terraced into the mountain's side."

- ^ About Seton Hall, Seton Hall University. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Climate and monthly weather forecast South Orange, NJ, Weather-US. Accessed February 19, 2023.

- ^ Report on Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Part I, p. 238. United States Census Bureau, 1895. Accessed October 20, 2016.

- ^ Compendium of censuses 1726-1905: together with the tabulated returns of 1905, New Jersey Department of State, 1906. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions, 1910, 1900, 1890, United States Census Bureau, p. 3365. Accessed May 24, 2012.

- ^ Fifteenth Census of the United States : 1930 - Population Volume I, United States Census Bureau, p. 712. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Table 6: New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1940 - 2000, Workforce New Jersey Public Information Network, August 2001. Accessed May 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Census 2000 Profiles of Demographic / Social / Economic / Housing Characteristics for South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey Archived January 16, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, United States Census Bureau. Accessed August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1: Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 - Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed August 21, 2013.

- ^ 2010 Census: Essex County, Asbury Park Press. Accessed June 14, 2011.

- ^ Sheskin, Ira M. The 2012 MetroWest Jewish Population Update Study, Jewish Data Bank, April 2013. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics from the 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates for South Orange Village township, Essex County, New Jersey Archived February 12, 2020, at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Department of Recreation and Cultural Affairs, South Orange Village. Accessed July 15, 2006.

- ^ Hatala, Greg. "Glimpse of History: Splashing around in South Orange", The Star-Ledger, July 28, 2014. "In this photo from 1958, children in South Orange are having a blast in one of the first free community pools in the country. According to the South Orange Historical and Preservation Society, the pool, built in the 1920s, was part of a recreation area known as Cameron Field."

- ^ Kofsky, Jared. "Officials Announce Federal Grant for South Orange River Greenway Project", Essex County Place, August 26, 2015. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- ^ Facilities, South Orange Village. Accessed October 13, 2024.

- ^ Giants of Jazz at The Baird, The Baird. Accessed November 26, 2013. "Honoring 2013 Jazz Master: Gary Bartz - Presented by SOPAC, The Baird and the Village of South Orange"

- ^ Giants of Jazz, South Orange Performing Arts Center. Accessed November 26, 2013. "Presented by SOPAC, The Baird and the Village of South Orange"

- ^ About the Gallery, Pierro Gallery of South Orange. Accessed November 26, 2013. "Operating under the aegis of the South Orange Department of Recreation and Cultural Affairs, the Pierro Gallery's mission is to offer experience and exposure to contemporary visual artists and to our communities through an array of gallery functions."

- ^ About SOPAC, South Orange Performing Arts Center. Accessed October 13, 2024.

- ^ Falkenstein, Michelle. "Around the Scene, a Whirl of Change", The New York Times, December 31, 2006. Accessed November 26, 2013. "The arts center, which consists of a 415-seat live performance space and a five-screen movie complex, had its genesis 12 years ago when a study commissioned by South Orange Village found that such a center would help revitalize downtown. The performance space was opened by the comedian Paula Poundstone on Nov. 3, and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma and the jazz clarinetist Paquito D'Rivera performed at the center's fund-raising gala later that month."

- ^ "Try something new at open rehearsal of S.O. Symphony". Essex News Daily. August 31, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ "Maplewood, South Orange fire department merger appears to be working well, leaders say", Essex News Daily, August 14, 2022. Accessed July 5, 2023. "The South Orange and Maplewood fire departments were dissolved and combined into the South Essex Fire Department on July 1, finally ending a years-long saga that saw debate over whether or not the two departments should become one. The merger was finalized in April, when both the South Orange Board of Trustees and the Maplewood Township Committee passed resolutions authorizing the towns to form a regional fire service; the first joint meeting was held on April 8."

- ^ About Us, South Orange Rescue Squad. Accessed March 27, 2022. "The South Orange Rescue Squad was established in 1952 by a group of local residents and business owners as an all-volunteer organization. At that time, a single ambulance was housed in a garage across Sloan Street from the Fire Department."

- ^ Inventory of Municipal Forms of Government in New Jersey, Rutgers University Center for Government Studies, July 1, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ "Forms of Municipal Government in New Jersey", p. 15. Rutgers University Center for Government Studies. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Village Council, South Orange Village. Accessed May 2, 2024. "South Orange Village's governing body is comprised of an elected Village Council consisting of six elected Councilmembers and an elected Mayor, all seven of whom serve four-year terms without any remuneration. Three Councilmembers are elected biennially."

- ^ 2024 Municipal Data Sheet, South Orange Village. Accessed March 24, 2024.

- ^ Essex County Directory, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed March 1, 2024.

- ^ May 9, 2023 Municipal Election Unofficial Results, Essex County, New Jersey Clerk, May 18, 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023.

- ^ Municipal Election May 11, 2021 Unofficial Results, Essex County, New Jersey, updated May 11, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- ^ Mann, Mary Barr."South Orange Says ‘Farewell’ to Trustee Zuckerman, Appoints Schnall to Finish Term", The Village Green of Maplewood and South Orange, September 13, 2022.Accessed March 1, 2023. "The South Orange Board of Trustees and Village President said farewell to Trustee Bob Zuckerman at the September 12, 2022 Board of Trustees meeting and appointed former Trustee Steve Schnall to fill out the remainder of Zuckerman’s term."

- ^ Maynard-Parisi, Carolyn. "Collum Sworn in as 49th — and First Woman — South Orange Village President", The Village Green of Maplewood & South Orange, May 18, 2015. Accessed May 20, 2015. "Before an enthusiastic audience of current and former elected officials, Village staff, family members, supporters and citizens, Sheena Collum made history Monday night as she was sworn in as South Orange's 49th — and first female — Village President. Incumbents Deborah Davis Ford, Howard Levison and Mark Rosner also were sworn in as members of the Board of Trustees at the ceremony at the South Orange Performing Arts Center (SOPAC)."

- ^ Lee, Eunice. "Election results for 2013 Essex County non-partisan municipal races", The Star-Ledger, May 14, 2013. Accessed August 22, 2013. "South Orange voters elected Walter Clarke, Sheena Collum and Stephen Schnall by a comfortable margin. The three newcomers comprised the South Orange 2013 team, which was endorsed by Village President Alex Torpey and several trustees on the seven-member board. Incumbent trustees Janine Bauer, Michael Goldberg and Nancy Gould did not seek re-election."

- ^ Staff. "South Orange Voters Elect New Village President", South Orange Village, May 17, 2011. Accessed May 29, 2011.

- ^ 2011 Municipal Election - Unofficial Results May 10, 2011, Essex County, New Jersey Clerk. Accessed May 24, 2012.

- ^ Khavkine, Richard. "South Orange voters elect incumbent and running-mates", The Star-Ledger, May 12, 2009. Accessed May 24, 2012. "In South Orange, incumbent Michael Goldberg and running mates Janine Bauer and Nancy Gould, running under the moniker 'Pure Progress', swept aside a trio of challengers, including former trustee Stephen Steglitz."

- ^ 2022 Redistricting Plan, New Jersey Redistricting Commission, December 8, 2022.

- ^ Districts by Number for 2023-2031, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed September 18, 2023.

- ^ 2011 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government Archived June 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, p. 64, New Jersey League of Women Voters. Accessed May 22, 2015.

- ^ Directory of Representatives: New Jersey, United States House of Representatives. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- ^ U.S. Sen. Cory Booker cruises past Republican challenger Rik Mehta in New Jersey, PhillyVoice. Accessed April 30, 2021. "He now owns a home and lives in Newark's Central Ward community."

- ^ https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/andy-kim-new-jersey-senate/

- ^ Legislative Roster for District 28, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed January 18, 2024.

- ^ Essex County Executive, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ General Information, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020. "The County Executive, elected from the County at-large, for a four-year term, is the chief political and administrative officer of the County.... The Board of Chosen Freeholders consists of nine members, five of whom are elected from districts and four of whom are elected at-large. They are elected for three-year concurrent terms and may be re-elected to successive terms at the annual election in November. There is no limit to the number of terms they may serve."

- ^ Robert Mercado, Commissioner, District 1, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Wayne L. Richardson, Commissioner President, District 2, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Tyshammie L. Cooper, Commissioner, District 3, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Leonard M. Luciano, Commissioner, District 4, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Carlos M. Pomares, Commissioner Vice President, District 5, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Brendan W. Gill, Commissioner At-large, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Romaine Graham, Commissioner At-large, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Newark Native Elected As County Commissioner: A'Dorian Murray-Thomas, Patch. Accessed January 10, 2024.

- ^ Patricia Sebold, Commissioner At-large, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Members of the Essex County Board of County Commissioners, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Breakdown of County Commissioners Districts, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ 2021 County Data Sheet, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- ^ County Directory, Essex County, New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- ^ About The Clerk, Essex County Clerk. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Members List: Clerks, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ About the Register, Essex County Register of Deeds and Mortgages. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- ^ Members List: Registers, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Armando B. Fontura, Essex County Sheriff's Office. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- ^ Members List: Sheriffs, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ The Essex County Surrogate's Office, Essex County Surrogate. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ Members List: Surrogates, Constitutional Officers Association of New Jersey. Accessed July 20, 2020.

- ^ "NJ DOS - Division of Elections - Summary of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast". www.state.nj.us. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "Presidential General Election Results - November 6, 2012 - Essex County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 6, 2012 - General Election Results - Essex County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. March 15, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2008 Presidential General Election Results: Essex County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 23, 2008. Accessed November 6, 2012.

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election: Essex County, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 13, 2004. Accessed November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Governor - Essex County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Number of Registered Voters and Ballots Cast - November 5, 2013 - General Election Results - Essex County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Elections. January 29, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ 2009 Governor: Essex County Archived February 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of State Division of Elections, December 31, 2009. Accessed November 6, 2012.

- ^ District information for South Orange-Maplewood School District, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed April 1, 2021.

- ^ School Data for the South Orange-Maplewood School District, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed April 1, 2021.

- ^ Montrose Early Childhood Center, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Seth Boyden Elementary Demonstration School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Clinton Elementary School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Jefferson Elementary School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Marshall Elementary School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ South Mountain Elementary School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ South Mountain Elementary School Annex, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Tuscan Elementary School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Maplewood Middle School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ South Orange Middle School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Columbia High School, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ Our Schools, South Orange-Maplewood School District. Accessed October 28, 2021.

- ^ New Jersey School Directory for the South Orange-Maplewood School District, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed February 1, 2024.

- ^ Home Page, Our Lady of Sorrows School. Accessed February 19, 2023. "Founded in 1890, Our Lady of Sorrows School is rooted in the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church while striving to employ current technologies and modern teaching methods."

- ^ Essex County Elementary Schools, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark. Accessed February 19, 2023.

- ^ "Nuns Clash With Neighbors, South Orange Officials Over Marylawn Academy Property", TAP into SOMA, January 8, 2013. Accessed July 14, 2022. "Maryland of the Oranges Academy, in South Orange, faced a decision increasingly common for private Catholic schools – lack of funding that has left its administration without any other choice but to close the school. The school will close at the end of the 2012-2013 school year. The decision was made in October, according to Sister Joan Repka of the Sisters of Charity of St. Elizabeth, chairwoman of the Marylawn board of trustees."

- ^ Delozier, Alan. "Seton Hall University — A History in Brief (1856-2006)", Seton Hall University. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Essex County Mileage by Municipality and Jurisdiction, New Jersey Department of Transportation, May 2010. Accessed July 18, 2014.

- ^ County Route 510 Straight Line Diagram, New Jersey Department of Transportation, updated July 2012. Accessed February 19, 2023.

- ^ County Route 577 Straight Line Diagram, New Jersey Department of Transportation, updated June 2012. Accessed February 19, 2023.

- ^ Essex County Highway Map, New Jersey Department of Transportation. Accessed February 19, 2023.

- ^ "South Orange Station 17 Sloan St South Orange, NJ Commuter Rail Stations". MapQuest. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "Mountain Station NJ Transit-M and E Gladstone Branch". MapQuest. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "NJ Transit Morris & Essex Line". NJ Route 22. May 10, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Essex County Bus / Rail Connections, NJ Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as May 22, 2009. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Route 31 Schedule, NJ Transit, issues January 13, 2024. Accessed May 2, 2024.

- ^ Jitney Bus, South Orange Village. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- ^ Station History, WSOU-FM Seton Hall Pirate Radio. Accessed March 25, 2012.

- ^ Newspaper Members - Worrall Community Newspapers, Inc., New Jersey Press Association. Accessed April 15, 2015.

- ^ About Us, The Village Green of Maplewood and South Orange. Accessed October 7, 2015. "The Village Green provides day-to-day, granular news coverage of the issues that matter to the people of Maplewood, South Orange, and environs — including education, redevelopment, taxes, public safety, governance, local business, the arts and culture, and lifestyle — with fairness, thoroughness, humanity and a distinct voice."

- ^ Home Page, South Orange, NJ Patch. Accessed July 14, 2022.

- ^ "Gaslight Newsletter | South Orange Village, NJ". www.southorange.org. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Fickenscher, Lisa. "N.J. town plans to launch affinity card program. (South Orange, New Jersey)", American Banker, April 8, 1994. Accessed March 25, 2012. "South Orange, N.J. – Mayor William R. Calabrese has big plans for this municipality. By June, the mayor expects to unveil an affinity credit card that would offer the 17,500 residents of the largely middle-class township discounts when they patronize local merchants.... He believes South Orange would be the first to get a town-affiliated bank credit card off the ground."

- ^ Caldwell, Dave. "Living in | South Orange, N.J.: A Place to Feel Homey While Staying Hip", The New York Times, March 2, 2008. Accessed March 25, 2012. "One of the first same-sex civil unions in New Jersey was performed in South Orange in February 2007."

External links

edit- South Orange Village

- School Data for the South Orange-Maplewood School District, National Center for Education Statistics

- News-Record (newspaper serving Maplewood and South Orange since 1958)

- Orange Lawn Tennis Club

- South Orange Historical and Preservation Society

- South Orange-Maplewood Community Coalition on Race (Community organization providing information about town for prospective buyers and organizing events for current residents)

- South Orange-Maplewood Place (Website providing information about South Orange and Maplewood)

- South Orange-Maplewood School District

- School Performance Reports for the South Orange-Maplewood School District, New Jersey Department of Education

- South Orange Performing Arts Center

- The South Orange Public Library

- South Orange Rescue Squad (SORS)

- South Orange Village Center Alliance (Not-for-profit management entity of South Orange Village Special Improvement District)

- South Orange Symphony Orchestra (South Orange's community orchestra)